UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE After Tragedy: the Romance of the Lowly God DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Philosophical Inquiry Into the Development of the Notion of Kalos Kagathos from Homer to Aristotle

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2006 A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle Geoffrey Coad University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Coad, G. (2006). A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle (Master of Philosophy (MPhil)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/13 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NOTION OF KALOS KAGATHOS FROM HOMER TO ARISTOTLE Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Geoffrey John Coad School of Philosophy and Theology University of Notre Dame, Australia December 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Declaration v Acknowledgements vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Fish Hook and Some Other Examples 6 The Sun – The Source of Beauty 7 Some Instances of Lack of Beauty: Adolf Hitler and Sharp Practices in Court 9 The Kitchen Knife and the Samurai Sword 10 CHAPTER 2: Homer 17 An Historical Analysis of the Phrase Kalos Kagathos 17 Herman Wankel 17 Felix Bourriott 18 Walter Donlan 19 An Analysis of the Terms Agathos, Arete and Other Related Terms of Value in Homer 19 Homer’s Purpose in Writing the Iliad 22 Alasdair MacIntyre 23 E. -

French Sculpture Census / Répertoire De Sculpture Française

FRENCH SCULPTURE CENSUS / RÉPERTOIRE DE SCULPTURE FRANÇAISE ARCHIPENKO, Alexander Flat Torso 1914 chrome plated sculpture, with black marble base M.83.175.1 Los Angeles, California, Los Angeles County Museum of Art ARCHIPENKO, Alexander Flat Torso 1914, cast 1921-1922 polished bronze 2003.3 Richmond, Virginia, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts ARCHIPENKO, Alexander Torso c. 1921-1923 marble 95.9 Bloomington, Indiana, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University (formally Indiana University Art Museum) Page 1 ARCHIPENKO, Alexander Torso in Space 1936 bronze on wood base AC 2001.601 Amherst, Massachusetts, Mead Art Museum, Amherst College ARCHIPENKO, Alexander Torso in Space 1936 terracotta, metalized with bronze on painted wood base 58.24 New York, New York, Whitney Museum of American Art ARCHIPENKO, Alexander Torso in Space 1936, cast 1967 bronze 68.10 New York, New York, Whitney Museum of American Art ARCHIPENKO, Alexander Torso in Space 1936 bronze, 2/6 1971.001.002 Tucson, Arizona, University of Arizona Museum of Art ARCHIPENKO, Alexander Torso 1916 bronze 1958.5 Phoenix, Arizona, Phoenix Art Museum Page 2 ARCHIPENKO, Alexander White Torso c. 1920, after a marble of 1916 silvered bronze 277.1961 New York, New York, The Museum of Modern Art ARP, Jean/Hans Torso original marble 1931, this enlarged cast 1957 bronze 1966.55.1 Baltimore, Maryland, The Baltimore Museum of Art ARP, Jean/Hans Torso Fruit 1960 marble 66.108 Washington, D.C., District of Columbia, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution Page 3 ARP, Jean/Hans Torso-Kore 1958 bronze, edition 2/5 97.1991 Chicago, Illinois, The Art Institute of Chicago Page 4 ARP, Jean/Hans Torso 1953 white marble on polished black marble base SC 1956:13 Northampton, Massachusetts, Smith College Museum of Art ARP, Jean/Hans Torso of A Knight 1959 bronze 2006.03 Grand Rapids, Michigan, Frederik Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park BARTLETT, Paul Wayland Female Figure bronze Washington, D.C., District of Columbia, The National Gallery of Art BARTLETT, Paul Wayland Seated Female Torso c. -

The-Odyssey-Greek-Translation.Pdf

05_273-611_Homer 2/Aesop 7/10/00 1:25 PM Page 273 HOMER / The Odyssey, Book One 273 THE ODYSSEY Translated by Robert Fitzgerald The ten-year war waged by the Greeks against Troy, culminating in the overthrow of the city, is now itself ten years in the past. Helen, whose flight to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris had prompted the Greek expedition to seek revenge and reclaim her, is now home in Sparta, living harmoniously once more with her husband Meneláos (Menelaus). His brother Agamémnon, commander in chief of the Greek forces, was murdered on his return from the war by his wife and her paramour. Of the Greek chieftains who have survived both the war and the perilous homeward voyage, all have returned except Odysseus, the crafty and astute ruler of Ithaka (Ithaca), an island in the Ionian Sea off western Greece. Since he is presumed dead, suitors from Ithaka and other regions have overrun his house, paying court to his attractive wife Penélopê, endangering the position of his son, Telémakhos (Telemachus), corrupting many of the servants, and literally eating up Odysseus’ estate. Penélopê has stalled for time but is finding it increasingly difficult to deny the suitors’ demands that she marry one of them; Telémakhos, who is just approaching young manhood, is becom- ing actively resentful of the indignities suffered by his household. Many persons and places in the Odyssey are best known to readers by their Latinized names, such as Telemachus. The present translator has used forms (Telémakhos) closer to the Greek spelling and pronunciation. -

Attention Bishops of Scotland! Time Flies, Eternity Awaits…

Satirical, Catholic Truth serious, straight- Keeping the Faith. Telling the Truth. talking www.catholictruthscotland.com https://catholictruthblog.com/ Attention Bishops of Scotland! Time Flies, Eternity Awaits… When Pope John Paul II looked out of the were re-opened, placing Christ the King in a Yet, in both Church circles and in the media, window of the home in which he grew up in position subordinate to questionable, selective you are regarded as mere diplomats who are Poland, he saw a sundial inscribed with the science and the diktats of a secular state. expected to subscribe to a wholly superficial words “Time Flies, Eternity Awaits” (Polish: relationship with the world; you must “go- Czas Ucieka Wieczność Czeka). along-to-get-along” with politicians, leaders of non-Catholic religions and others in public A sobering thought. A thought which is, in life. This has been the modus operandi of fact, at the very heart of the Gospel: “Stay bishops and priests for years now. You should awake, for you do not know the day nor the find the thought of being called to judgment hour…” (Matt 25:13) with such a curriculum vitae, terrifying. As recently as 13 January 2021, the Feast of Pope Benedict XV repeats what the Fathers St Mungo, Patron Saint of Glasgow, Philip When he penned his Christmas address to the of the Church have always taught as necessary Tartaglia, the Archbishop of Glasgow, was faithful, in which he lamented the “strangeness” for salvation: called to his judgment. Think about that: the of this Christmas, Archbishop Tartaglia could Archbishop, whose God-given mandate to “The nature of the Catholic faith is such that not have known that his “day and hour” was fast teach and preach Christ in that city, was called nothing can be added to it, nothing taken approaching - that eternity awaited. -

Gay Knights and Gay Rights: Same-Sex Desire in Late Medieval Europe and Its Presence in Arthurian Literature

Gay Knights and Gay Rights: Same-Sex Desire in Late Medieval Europe and its Presence in Arthurian Literature MA Thesis Philology Student Name: Dorien Zwart Student Number: 1564137 Date: 10 July 2019 First Reader: Dr. K.A. Murchison Second Reader: Dr. M.H. Porck Leiden University, Department of English Language and Culture Image description: Lancelot, Galehaut and Guinevere. Lancelot and Guinevere kiss for the first time while Galehaut watches in the middle. Image from a Prose Lancelot manuscript, Morgan Library, MS M.805, fol. 67r. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter 1 – The Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries: The Development of Queer Europe 6 Chapter 2 – “Des Femmez n’Avez Talent” [You Have No Interest in Women]: Same-Sex Subtext in Marie de France’s Lanval 21 Chapter 3 – The Thirteenth Century: The Increase of Intolerance 28 Chapter 4 – “Se Tout li Mondes Estoit Miens, se Li Oseroie Je Tout Douner” [If All the World Were Mine, I Wouldn’t Hesitate to Give it to Him]: Lancelot and Galehaut: a Same-Sex Romance in a Homophobic Century 41 Chapter 5 – England in the Fourteenth Century: Knights, Kings, and the Power of Accusation 67 Chapter 6 – “He Hent þe Haþel Aboute þe Halse, and Hendely Hym Kysses” [He Catches Him by the Neck and Courteously Kisses Him]: Desire in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 80 Conclusion 90 Bibliography 93 INTRODUCTION Same-sex desire in medieval literature has been of interest to modern scholars for only several decades. Since the nineties, a popularity for rereading medieval literary works in order to uncover as of yet unfrequently-discussed same-sex elements has been growing steadily.1 This form of rereading, commonly called “queering” historical literature, generally aims to highlight homosocial affection and explore its potentially homoromantic connotations within their historical contexts. -

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife Joel P. Christensen Brandeis University [email protected] Abstract This article examines the development of the theme of eris in Hesiod and Homer. Start- ing from the relationship between the destructive strife in the Theogony (225) and the two versions invoked in the Works and Days (11–12), I argue that considering the two forms of strife as echoing zero and positive sum games helps us to identify the cultural and compositional force of eris as cooperative competition. After establishing eris as a compositional theme from the perspective of oral poetics, I then argue that it develops from the perspective of cosmic history, that is, from the creation of the universe in Hes- iod’s Theogony through the Homeric epics and into its double definition in the Works and Days.To explore and emphasize how this complementarity is itself a manifestation of eris, I survey its deployment in our major extant epic poems. Keywords eris – competition – conflict – poetics – rivalry In Cypria fr. 1, Zeus fans “the flames of the great strife of the Trojan war / to lighten the [earth’s] burden with death” (ῥιπίσσας πολέμου μεγάλην ἔριν Ἰλιακοῖο, 5).* Similarly, in Hesiod (fr. 204 M-W), when strife divides the gods at the birth of Hermione—“all the gods were of two minds / because of the strife” (πάν- τες δὲ θεοὶ δίχα θυμὸν ἔθεντο / ἐξ ἔριδος, 94–95)—Zeus hastens the destruction of the Heroes: “And then he hastened to extinguish the great race of human * A version of this article was given at the Heartland Graduate Conference in Ancient Stud- ies at the University of Missouri in 2015. -

“100% Sanctification – Guaranteed” – Part 2 100% Sanctification

THE SECOND EPISTLE OF PETER TO THE CHURCH OF THE DISPERSION THROUGHOUT THE WORLD 2 PETER CHAPTER 1:5-9 MEDIA REFERENCE NUMBER SMX995 OCTOBER 27, 2019 THE TITLE OF THE MESSAGE: “100% Sanctification – Guaranteed” – Part 2 SUBJECT TOPICALLY REFERENCED UNDER: Faithfulness, Finishing, Church, Christianity, Discipleship 2 Peter 1:5-9 But also for this very reason, giving all diligence, add to your faith virtue, to virtue knowledge, 6 to knowledge self-control, to self-control perseverance, to perseverance godliness, 7 to godliness brotherly kindness, and to brotherly kindness love. 8 For if these things are yours and abound, you will be neither barren nor unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. 9 For he who lacks these things is shortsighted, even to blindness, and has forgotten that he was cleansed from his old sins. 100% Sanctification – Guaranteed! We have read throughout the Old Testament that God called His people to be set apart from this world and to be set apart for Him That Old Testament Requirement is Fulfilled in the New Testament Relationship And in Peter’s Day - The Early Church was Increasingly Thankful for that. It’s success / It’s effect / It’s influence / It’s earthly calling / From its heavenly position. 1 Thessalonians 5:23-24 Now may the God of peace Himself sanctify you completely; and may your whole spirit, soul, and body be preserved blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. 24 He who calls you is faithful, who also will do it. Reviewing Part 1 of Our Previous Teaching 100% Sanctification – Guaranteed! 1.) Means that we co-operate with God vs. -

The Cyclops in the Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts

THE CYCLOPS IN THE ODYSSEY, ULYSSES, AND ASTERIOS POLYP: HOW ALLUSIONS AFFECT MODERN NARRATIVES AND THEIR HYPOTEXTS by DELLEN N. MILLER A THESIS Presented to the Department of English and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts December 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Dellen N. Miller for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of English to be taken December 2016 Title: The Cyclops in The Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts Approved: _________________________________________ Paul Peppis The Odyssey circulates throughout Western society due to its foundation of Western literature. The epic poem thrives not only through new editions and translations but also through allusions from other works. Texts incorporate allusions to add meaning to modern narratives, but allusions also complicate the original text. By tying two stories together, allusion preserves historical works and places them in conversation with modern literature. Ulysses and Asterios Polyp demonstrate the prevalence of allusions in books and comic books. Through allusions to both Polyphemus and Odysseus, Joyce and Mazzucchelli provide new ways to read both their characters and the ancient Greek characters they allude to. ii Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank Professors Peppis, Fickle, and Bishop for your wonderful insight and assistance with my thesis. Thank you for your engaging courses and enthusiastic approaches to close reading literature and graphic literature. I am honored that I may discuss Ulysses and Asterios Polyp under the close reading practices you helped me develop. -

August-Ias-Express-Final.Pdf

August 2017 IAS EXPRESS RajasirIAS.com A monthly Current Affairs Booklet CONTENT Pg.No. Doklam Dare – Decoded – Monthly Focus Study Less ! Write Well ! Score More! Approach to Sociology Sociology – Model Question Paper with Answers 1. ECONOMY 1.1 Bitcoin trade may come under SEBI 1 1.2 India to join new global foreign exchange committee 2 1.3 Aaykar Setu 3 1.4 Programme 17 for 17 3 1.5 RBI considering setting up a Public Credit Registry 3 1.6 SEBI to move against non-compliant firms 4 1.7 Scheme for IPR Awareness – Creative India; Innovative India 5 1.8 Integration of oil & gas majors is best avoided 6 1.9 BharatNet deadline pushed to March 2019 7 1.10 First meeting of Integrated Monitoring and Advisory Council (IMAC) 8 1.11 Government mulls insurance cover for digital transaction frauds 8 1.12 5th Global Conference on Cyber Space (GCCS) 9 1.13 MPC members to get Rs. 1.5 lakh per meet, must disclose assets 10 1.14 Govt considering new agency to keep check on chartered accountants 12 1.15 India performs miserably in war on inequality 13 1.16 Finance Minister releases National Trade Facilitation Action Plan 13 1.17 223 anti-dumping probes initiated by India since January 2012 15 1.18 FSSAI bans stapler pins in tea bags from January 2018 16 1.19 The Banking Regulation (Amendment) Bill 2017 introduced in Lok Sabha 17 1.20 Transfer unclaimed accruals to fund: IRDA 18 1.21 India‟s Alternate Governor on the Board of Governors of ADB 18 1.22 NMCE and ICEX to merge, creating India‟s third largest commodity exchange 20 2. -

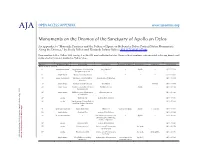

Supplemental Content: Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary Of

AJA OPEN ACCESS: APPENDIX www.ajaonline.org Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary of Apollo on Delos An appendix to “Honorific Practices and the Politics of Space on Hellenistic Delos: Portrait Statue Monuments Along the Dromos,” by Sheila Dillon and Elizabeth Palmer Baltes (AJA 117 [2013] 207–46). Base numbers follow Vallois 1923 (see fig. 3 in the AJA print-published article). Bases without numbers were recorded as having been found in the area but were not marked on Vallois’ plan. Base No. Monument Type Honorand(s) Dedicator(s) Reason(s) for Honor Dedicated to Sculptor(s) Reference(s) Bases set up ca. 250–200 5 equestrian statue Epigenes, son of Andron, the King Attalos I – Apollo – IG 11 4 1109 Pergamene general 8 single statue Donax, son of Apollonios – – – – IG 11 4 1202 16 group monument Aischylo(. .) and his father, Mennis, son of Nikarchos – – – IG 11 4 1168 Nikarchos 19 single statue female, Hellenistic queen? the Delians – – Thoinias IG 11 4 1088 20 single statue Autokles, son of Ainesidemos, Autokles, his son – Apollo – IG 11 4 1194 from Chalcidia 117.2) 25 single statue Phildemos, son of Pythermos Eumedes, his son – – – IG 11 4 1193 of Chalcedon 27 exedra family group demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1090 33 exedra family group of Jason, Eukleia, – – – – IG 11 4 1203 Timokleia, Straton, Timokleia, Sillis 41 victory monument Gallic dedication Attalos I(?) victory over Gauls Apollo (. .)epoiei IG 11 4 1110 50c single statue Aichmokritos demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1094 American Journal of Archaeology American 53 -

The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves

1616796596 The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves By Jenni Bergman Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University 2011 UMI Number: U516593 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516593 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted on candidature for any degree. Signed .(candidate) Date. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed. (candidate) Date. 3/A W/ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 4 - BAR ON ACCESS APPROVED I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan after expiry of a bar on accessapproved bv the Graduate Development Committee. -

The Oracle and Cult of Ares in Asia Minor Matthew Gonzales

The Oracle and Cult of Ares in Asia Minor Matthew Gonzales ERODOTUS never fails to fascinate with his rich and detailed descriptions of the varied peoples and nations H mustered against Greece by Xerxes;1 but one of his most tantalizing details, a brief notice of the existence of an oracle of Ares somewhere in Asia Minor, has received little comment. This is somewhat understandable, as the name of the proprietary people or nation has disappeared in a textual lacuna, and while restoring the name of the lost tribe has ab- sorbed the energies of some commentators, no moderns have commented upon the remarkable and unexpected oracle of Ares itself. As we shall see, more recent epigraphic finds can now be adduced to show that this oracle, far from being the fantastic product of logioi andres, was merely one manifestation of Ares’ unusual cultic prominence in south/southwestern Asia Minor from “Homeric” times to Late Antiquity. Herodotus and the Solymoi […] 1 The so-called Catalogue of Forces preserved in 7.61–99. In light of W. K. Pritcéhesttp’s¤ dtahwo rodu¢g h» mreofbuota˝tnioanws eo‰xf osunc hs mscihkorlãarws, aksa O‹ .p rAorbmÒalyoru, wD . FehdlÊinog ,l aunkdio Se.r Wg°eastw, ßwkhaos steoekw teo‰x dei,s c§rped‹ idt ¢th teª asuit hkoerfitay loªf sHie krordãontuesa o n thixs ãanldk eoath:e pr rpÚowin dts¢, tIo w›silli skimrãplnye rseif eŒr ttãhe t ree kadae‹r kto° rPerait cphreotts’s∞ tnw ob omÚawj or trexatãmleknetas ,o f t§hpe∞irs waonr k,d S¢t udkieas i‹n AlnÒcifenot i:G reetkå Two podg¢ra phkyn IÆVm (aBwe rk=eãleky e1s9i8 2) 23f4–o2in85ik a°nodi sTih ek Laiatre Silch¤xoola otf oH.