Mental Strategies and Tools for Endurance Cycling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Alps & the Jura

© Lonely Planet 238 A R JU E H T & S P L French Alps & the Jura NCH A RE HIGHLIGHTS F Conquering the Alpe d’Huez (p261) Teetering on the edge of the Gorges da la Bourne (p242) Slowly approaching the hilltop, medieval-fortified village of Nozeroy (p255) Conquering the highest pedalled pass – Col du Galibier 2645m (p241) TERRAIN Extremely mountainous in the Alps, and mainly rolling hills in the Jura with some real lung-crushers from time to time. Telephone Code – 03 www.franche-comte.org www.rhonealpestourisme.com Awesome, inspiring, tranquil, serene – superlatives rarely do justice to the spectacular landscapes of the French Alps and the Jura. Soaring peaks tower above verdant, forested valleys, alive with wild flowers. Mountain streams rush down from dour massifs, carving out deep gorges on their way. Mont Blanc, Grandes Jorasses and Barre des Écrins for mountaineers. Val d’Isère, Chamonix and Les Trois Vallées for adrenaline junkies. Vanoise, Vercors and Jura for great outdoors fans. So many mythical names, so many expectations, and not a hint of flagging: the Alps’ pulling power has never been so strong. What is so enticing about the Alps and the Jura is their almost beguiling range of qualities: under Mont Blanc’s 4810m of raw wilderness lies the most spectacular outdoor playground for activities ranging from skiing to canyoning, but also a vast historical and architectural heritage, a unique place in French cuisine (cheese, more cheese!), and some very happening cities boasting world-class art. So much for the old cliché that you can’t have it all. -

Alpine Cols of the Tour De France Trip Notes

Current as of: July 22, 2019 - 09:22 Valid for departures: From January 1, 2017 to January 1, 2021 Alpine Cols of the Tour de France Trip Notes Ways to Travel: Guided Group 8 Days Land only Trip Code: Destinations: Italy, Adventure Holidays in Min age: 16 MWU Challenging / France Tough Programmes: Cycling Trip Overview This epic ride starts in the charming Italian town of Cuneo, before climbing into France in search of some of the most iconic climbs in cycling history. The rst big challenge is the Col de la Bonnette, at 2802m the highest col in Europe and a favourite of Robert Millar. From here on the legendary climbs come in quick succession as we make our way across the spectacular cols of Vars, Izoard, Galibier and Croix de Fer. We nish the route by tackling the famous 21 hairpins bends to Alpe d’Huez, a memorable nish to a memorable trip! At a Glance 6 days cycling with partial vehicle support (limited seats) 100% tarmac roads Climbs are long and steady (average 7%) Group normally 4 to 16 plus leader in support vehicle 7 nights hotels Countries visited: Italy, Adventure Holidays in France Trip Highlights Cycle through the Italian and French Alps Conquer the highest paved road in Europe Finish with an ascent of the iconic Alpe d'Huez Is This Trip for You? This trip is classied Drop Bars Activity Level: 6 (Challenging/Tough) 6 days cycling with partial vehicle support (limited seats) Average daily distance of 72km a day (45 miles) with an average elevation gain of 1900m a day. -

Cols Mythiques Du Briançonnais

Séjour cyclisme dans les Hautes-Alpes: Cols mythiques du Briançonnais Un grand choix d’itinéraires pour les passionnés de vélo qui veulent se mesurer aux- Alpescols my- ! thiques du Tour de France, ou simplement pédaler dans les hauteurs des Hautes Les cols mythiques du Tour de France Des boucles spécialement aménagées Au cœur des Alpes françaises, le Briançonnais compte de nom- Des parcours cyclistes appelés « itinéraires breux cols très appréciés des cyclistes et rendus célèbres grâce partagés » ont été spécialement mis en place aux passages du Tour de France. et balisés par le conseil départemental: dans le Le col du Galibier (2058m) offre une vue saisissante sur le parc Briançonnais, plusieurs parcours entre 40 et des Ecrins et sur la Meije ; le col de l’Izoard (2360m), franchi à 32 120km attendent les amoureux de la petite reprises par le Tour de France, vous promet une vue imprenable reine dans des paysages contrastés, des petites sur les sommets du Briançonnais et du Queyras. Le col du Granon routes sinueuses aux grands balcons, avec des et celui du Lautaret n’ont rien à leur envier et vous promettent panoramas à couper le souffle ! également de superbes montées ! Opération «cols réservés »: Chaque été, généralement en juillet, 5 cols du département sont fermés à la circulation motorisée pour les réser- ver aux cyclistes l’espace d’une matinée. Un ravitaillement est même organisé au pied des cols et à l’arrivée. Une initiative qui vous permet de gravir les cols en sécurité, et en silence ! D’autres activités pour varier votre séjour Si vous souhaitez varier vos activités pendant votre séjour ou simplement reposer vos jambes après un col particulièrement éprouvant, de nombreuses activités sont possibles au départ de nos hébergements : A 10 minutes de Chantemerle se trouve la ville de Briançon, une ville d’art et d’histoire dont les fortifications Vauban sont classées au patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO. -

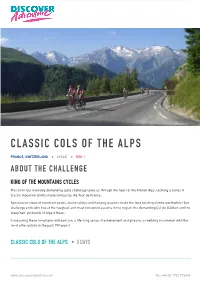

Challenge Notes

CLASSIC COLS OF THE ALPS FRANCE, SWITZERLAND • CYCLE • RED 1 ABOUT THE CHALLENGE KING OF THE MOUNTAINS CYCLES This short but intensely demanding cycle challenge takes us through the heart of the French Alps, tackling a series of classic mountain climbs made famous by the Tour de France. Spectacular views of mountain peaks, alpine valleys and hanging glaciers make the long twisting climbs worthwhile! Our challenge ends with two of the toughest and most renowned ascents in the region: the demanding Col du Galibier and the steep hair-pin bends of Alpe d’Huez. Conquering these mountains will earn you a life-long sense of achievement and give you something in common with the most elite cyclists in the past 100 years! CLASSIC COLS OF THE ALPS • 5 DAYS www.discoveradventure.com Tel: +44 (0) 1722 718444 PAGE 2 CLASSIC COLS OF THE ALPS Day 1: Arrive Geneva/Meet Annecy* Annecy is a beautiful lakeside town in the French Alps, approx 1½ hours from Geneva. Depending on your flight times, you can either take the group transfer from Geneva or meet at our hotel. After assembling and checking your bike, you can explore the picturesque narrow streets of Annecy. Night hotel. (Lunch not included) *One airport transfer from Geneva to Annecy will be provided at a pre-arranged time. Day 2: Annecy – Col des Aravis – Col des Saisies – Albertville Up early for our first day in the saddle! Heading out of Annecy, the valley terrain provides a perfect warm-up as we head towards the ski-resort town of La Clusaz. -

Last 10 Days Saturday July 18Th to Monday July 27Th 2015 102Nd Tour De France - Last 10 Days 2015

2015 Last 10 Days Saturday July 18th to Monday July 27th 2015 102nd Tour de France - Last 10 Days 2015 www.kathywatt.com 1. 102nd Tour de France - Last 10 Days 2015 Last 10 Days From Saturday July 18th to Monday July 27th 2015 LIVE YOUR PASSION FOR CYCLING ON OUR TOURS, YOU ARE MORE THAN JUST A SPECTATOR 10 days, 7 nights in 4* hotels and 2 nights in 3* hotels on half-board basis Start: Lyon, Finish: Paris Tour de France viewings: 7 Staff: 3 It can still surprise! The 2015 Tour de France route was designed with the intention of breaking away from tradition. The plains, mountains and time trial are clearly included in the 102th edition... but in unprecedented proportions and with nuances susceptible of upsetting pre- established plans. For its 102th edition, the Tour de France offers its riders a challenge that invites daring and will leave its television viewers in a state of uncertainty regarding the scenarios to consider. The premise of suspense and indecision has indeed been favored; the questioning of non-written regulations that can often weigh on the race is gone. Also, the riders will only have 14 kilometres of individual time trial to show their stuff, making it the shortest distance since its systematic inclusion in 1947. ”The desire is to not hold up the race”, said Christian Prudhomme, getting rid of rules and dogmas of all kinds. When the first portion of the 2015 Tour takes the peloton from Utrecht and The Netherlands to the heart of Brittany, passing by the landmarks of the Spring Classics or along the Normandy coast, the Tour boss sees much more than a long week of flatlands: “Do not imagine that it will be a nagging procession. -

Revue Mondained Aix Les Bains

J OU RNAL ETRANGER/ Revue Mondaine d Aix les BaIns ET D ET T ONT VOIAINE/ Rédaction et Administration : Imprimerie Paul FACQIKS 13, avenue de Tresserve AIX-LES-BAINS Tél. 0-78 Achetez vor Pyjamar (de, P&ris) de Traitement aux Xoimlle/ GaJerier Aix-les-Bains COMPTOIR NATIONAL D'ESCOMPTE DE PARIS Société Anonyme au Capital de 400.000.000 de francs entièrement versés Agences : AIX-LES BAINS ANNECY CHAMBERY Rue du Casino — Téléphone 2-85 Rues Royale et d'Italie — Téléphone 3-17 3, Place de l'Hôtel-de-Ville — Téléphone 4-17 Filiale à New-York : French-American Banking Corporation PAIEMENT DE LETTRES DE CREDIT ET DE CHEQUES — CHANGE DE MONNAIES ETRANGERES — OPERATIONS DE BANQUE ET DE TITRES Location de Compartiments de Coffres-Forts maison des touristes Corps Médical d'Aix-les Bains Renseignements HOTEL-RESTAURANT Médecins Pratiques ôertier, 12, rue Albert-Ier. 2.47 Cultes Avenue de Alarlioz, 4, et Avenue de Tresserve, 5 - Tél. 5 Blanc, place Carnot, 3. 3.60 a) Religion Catholique. Eglise, boule¬ Tout Confort — Craints Jardins Ombragés Blondel, rue de Genève. 26 2.05 vard des Côtes. Curé-Archiprêtre, M. le Spécialités Italiennes Bosonnet G., rue des Bains, 21. 7.52 Chanoine Jullien, 10, rue du Dauphin. Caructte R.. Institut Zander. Pension à partir de 35 francs 0.74 Téléph. 5.55. K- CERBONHSCHI, Chavériat, rue de Genève, 11. 4.37 propr. Services religieux: Semaine, Messes à 6 h., Chesneau, Revard, 4. 2.02 place du 7 h., 7 h. 30. Messe des baigneurs 9 h. (du Chevallier, avenue Marie, 6, et boulevard 15 juin au 15 septembre). -

One of the True Giants of the Alps, the Galibier Has Seen Many Battles

b Col du Galibier HC climbs hile race leader was found dead as the result of a Jan Ullrich cocaine overdose in a Rimini hotel cracked in on Valentine’s Day 2004 – a sad end the cold, wet to one of the most exciting, if flawed, weather, Marco riders of the modern age. W Pantani appeared galvanised. This was Stage 15 of the troubled 1998 Early years Tour de France, between Grenoble Happily, the Col du Galibier is more and Les Deux Alpes, which Pantani often the stage for hot, sunny days had started with a three-minute and happy memories. Situated in deficit to the German. It would the heart of the French Alps, on the require an explosive effort on northern edge of the Ecrins National his part to get back on terms. Park, the 2,642m-high Galibier will And so when he attacked on make its 63rd appearance in the Tour the Col du Galibier, Pantani gave it de France in 2017 (on the day that this everything. The Italian’s on-the-drops issue of Cyclist lands in shops). The climbing style mimicked the way the last time the Tour visited was in 2011, sprinters grip their handlebars, and when the Galibier featured in two he wouldn’t have been far off them stages. It made its first appearance in speed-wise, either. 1911 as one of four climbs to showcase On such a damp and grey the Alps, after the Pyrenees had been day, Ullrich’s equally grey pallor introduced to the race the year before. -

The Lautaret Alpine Botanical Garden Guidebook

The Lautaret Alpine Botanical Garden Guidebook Serge Aubert The Lautaret Alpine Botanical Garden, as it exists today, has been shaped by the work of the bota- nists involved in its development for over a century. This guide presents the Garden itself (its history, work and collections), the exceptional environment of the Col du Lautaret, and provides an intro- duction to botany and alpine ecology. The guidebook also includes the results of research work on alpine plants and ecosystems carried out at Lautaret, notably by the Laboratory of Alpine Ecology based in Grenoble. The Alpine Garden has a varied remit: it is open to the general public to raise their awareness of the wealth of diversity in alpine environments and how best to conserve it, it houses and develops a variety of collections (species from mountain ranges across the world, a seed bank, herbarium, arboretum, image bank & specialist library), it trains students and contributes to research in alpine biology. It is a university botanical garden which develops synergies between science and society, welcoming in 15,000 – 20,000 visitors each summer. Prior to 2005 the Garden was not directly involved in research, but since then a partnership has been established with the Chalet-Laboratory through the Joseph Fourier Alpine Research Station, and mixed structure of the Grenoble University and of the French Scientific Recearch Centre (CNRS). These shared facilities also include the Robert Ruffier-Lanche arboretum and the glasshouses on the Grenoble campus. The Lautaret site is the only high altitude biological research station in Europe, and has been recognised by the French government’s funding programme (Investissements d’ave- nir) as Biology and Health National Infrastructure (ANAEE-S) in the field of ecosystem science and experimentation. -

Tour Du Combeynot Il Faut Partir Du Col Du Lautaret Pour S’Enfoncer Dans Les Hautes Vallées Des Écrins

Pour faire le Tour du Combeynot il faut partir du col du Lautaret pour s’enfoncer dans les hautes vallées des Écrins. Dans ce décor de roche et de glaciers, sous l’impressionnante montagne des Agneaux, le Pic Gaspard ou la Meije (3983 m), l’itinéraire file entre alpages, forêts de mélèzes et ACCÈS & DU INFOS hameaux montagnards. Le long de la Romanche ou TOUR COMBEYNOT en bord de Guisane, la faune et la flore se dévoileront CONTACTS ENTRE CERCES ET ÉCRINS PRATIQUES à chaque pas, tout comme le riche patrimoine local. Refuge de Chamoissière Entre points d’intérêts et vues à couper le souffle, on chemine entre tradition et haute montagne. DE 3 À 6 JOURS Lille CARTES & GUIDES Carto-Guide Serre-Chevalier Vallée HÉBERGEMENTS Paris Cartes IGN 3435ET Valloire - Aiguilles d’Arves - Col du Galibier ÉTAPE 1 : Col du Lautaret > L’Alpe de Villar-d’Arène Strasbourg Rennes PARC 3536OT Briançon - Serre-Chevalier - Montgenèvre REFUGE DE L’ALPE Altitude 2079 m – 94 places 04 76 79 94 66 NATIONAL Nantes DE VILLAR-D’ARÈNE DES ÉCRINS Genève LES SERVICES PLUS REFUGE DE CHAMOISSIÈRE Altitude 2106 m – 18 places 09 82 12 46 24 Mâcon Lyon Taxi 06 79 53 45 67 Turin ÉTAPE 2 : L’Alpe de Villar-d’Arène > Le Casset Grenoble Aire optimale d’adhésion Bordeaux Valence du Parc Renseignements sur le parcours GÎTE-HÔTEL LE REBANCHON Le Casset - 05220 Le Monêtier-les-Bains 04 92 55 63 76 Centre d’accueil du Parc, au Col du Lautaret 04 92 24 49 74 Montpellier Gap Cœur du Parc Altitude 1512 m – 18 places Nice BRIANÇONNAIS & Centre d’accueil du Parc, au Casset 04 92 24 53 27 -

Col Du Galibier En Omgeving

TOURS & TIPS INFORMATIE Toeristenbureau: La Grave, in het centrum aan de N91, tel. 04 76 79 90 05, RUIG www.lagrave-lameije.com Jardin Botanique alpin du Lautaret: LANDSCHAP - sajf.ujf-grenoble.fr. COL DU GALIBIER Geopend juni tot half september, 10-18 uur. EN OMGEVING SPORT EN ACTIVITEITEN Wandelen, skiën, langlaufen, fietsen, parapente en klimmen: Bureau des Guides de La Grave-La Meije, Place du Téléphérique, tel. 04 76 79 90 21, www. guidelagrave.com. FRANSE ALPEN Meer mogelijkheden in Le Chazelet en Villar d’Arène. Confient Ciel: parapentecursussen voor beginners en gevorderden, La Grave, Over een heel smal, kronkelig bergweggetje bereikt u deze bergpas op 2646 m hoogte. tel. 06 75 02 33 81, www.confidentciel.fr Het is een van de beruchtste cols uit de Tour de France. Het landschap wordt steeds ruiger en onherbergzamer. U komt langs heel steile, kale bergwanden met schaarse begroeiing. OVERNACHTEN IN DE BERGEN De bergpas ligt tussen het stadje Saint-Michel- Ook de kerkklok is van emaille gemaakt, net als de-Maurienne bij de snelweg A43 en het veel andere klokken in de regio. Het interieur Hôtel La Meijette: Route Nationale de bergdorp La Grave. Bij mist of laaghangende van de kerk is erg donker en heeft een Grenoble, La Grave, tel. 04 76 79 90 34, bewolking is de route lastig te rijden en bij middeleeuwse atmosfeer. [email protected]. sneeuw wordt de weg afgesloten. In de buurt Tweesterrenhotel met mooi uitzicht op de van het hoogste punt staan veel teksten van VILLAR D’ARÈNE Meije, 2 pk vanaf € 58, ’s winters gesloten. -

Worldwide Adventures

CYCLING WORLDWIDE ADVENTURES 2018 EUROPE / ASIA / CENTRAL AMERICA / AFRICA Welcome to the Intrepid way of travel There’s nothing quite like jumping on a bike and exploring a city by road. In fact some cities, like Hanoi or Seville, seem to be built to do just that. While riding down cobbled streets and laneways sounds romantic (and it is), for me it’s all about hitting the open road – pedalling past Provence’s lavender fields, stopping by the side of the road in Tanzania to spot giraffe, or the satisfaction that comes with beating the hilly trails of Vinales. Perhaps the best bit about seeing it all on a bike is you can travel like a proper local, still get some exercise, and enjoy an environmentally friendly mode of transport. I believe that we have a responsibility as one of the world’s largest providers of adventure travel experiences to help conserve the environment for future generations. That’s why our commitment to responsible travel is so important to me. We’re always looking for ways to improve, from putting a stop to orphanage visits and elephant rides to carbon offsetting all our trips. Our not-for-profit arm, The Intrepid Foundation, also supports grassroots community projects around the world by matching traveller donations dollar-for-dollar. It’s crucial that we all play our part in making this a better world. In 2018 we’ve got a stack of pedal-powered trips to get excited about – designed specifically for riders of all levels and run by top-notch cycling guides. -

Freewheeling44-SCREE

t Australia Post ber RegiSPublicationer~d by No NBH2266 Septem . 1987 t 12 SPEED TRI-A The Tri-A features tight racing geometry for quick response, made of Tange DB Chro-Moly tubing and incorporates internal brake and derailleur wiring. Shimano 600EX throughout, Araya hard anodised rims and Panaracer Tri Sport tyres make this the intelligent choice for the discerning cyclist. 15 SPEED CRESTA A touring bicycle to the .end. The Cresta 7s builtwith emphasis on long distance touring. Frame features Tange No.2 and No.5 Cro Mo tubing, three biddon holqefS and extra eyelets to accommodate carriers. Drive train is Sugino TRT coupled to the new Suntour Mountech Tri pulley derailleur. Cantilever brakes, 40 spoke rear wheel and rear carrier completes this fine touring bicycle. • - - , Available from leading cycle dealers REPC:D C:YC:LES Number 44 September/October 1987 Contents 47 MOTOR MOUSE BECOMES SUPER CAT Danny Clark - six day champ 8ic1Jcle Traflel and Columns transport 5 W ARREN SALOMON 42 REFLECTIONS 6 DONHATCHER John Brown looks back 7 JOHNDR UMMOND at his US bike odyssey 12 PRO DEALERS 46 RIGHTSOF ACCESS 10 WRITE ON Every street is a bicycle 15 THE WORLD AWHEEL street 29 PHIL SOMERVILLE 8ic1Jcle clothin9 feature 68 CLASSIFIEDS 21 SUMMER FASHION 69 CALENDAR 1987/88 A four page colour feature Freewheeling is published six times a year in the months of January, 27 THE BIKES OF SUMMER March, May, July, September and Nove mber. ISSN No: 0156 4579 , Editorial and Advertising Offices: Room 57Trades Hall , cnr Dixon & This season's bike Goulburn Sts ., Sydney NS WAustralia.