This Article Continues the IBEW Journal's Commemoration of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politicized Worker Under the Labor-Management Reporting and D

Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal Volume 5 | Issue 2 Article 2 1988 The olitP icized Worker Under the Labor- Management Reporting and Disclosure Act Barry Sautman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Sautman, Barry (1988) "The oP liticized Worker Under the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act," Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal: Vol. 5: Iss. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj/vol5/iss2/2 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sautman: The Politicized Worker Under the Labor-Management Reporting and D ARTICLES THE POLITICIZED WORKER UNDER THE LABOR-MANAGEMENT REPORTING AND DISCLOSURE ACT Barry Sautman* THE LANDRUM-GRIFFIN "BILL OF RIGHTS" The "Bill of Rights of Members of Labor Organizations" was enacted as part of the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA)' [commonly known as the Landrum-Griffin Act of 1959]. The "Bill of Rights" was designed to ensure that individual labor union members can exercise, within their union, many of the same democratic rights that the polity can exercise under the Bill of Rights to the United States Constitution.' Title I of the LMRDA * B.A., M.L.S., J.D., University of California at Los Angeles; L.L.M., New York Uni- versity; PHD Candidate in Political Science, Columbia University; Associate, Shea & Gould, New York, New York. -

GLOSSARY of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING TERMS and SELECTED LABOR TOPICS

GLOSSARY of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING TERMS and SELECTED LABOR TOPICS ABEYANCE – The placement of a pending grievance (or motion) by mutual agreement of the parties, outside the specified time limits until a later date when it may be taken up and processed. ACTION - Direct action occurs when any group of union members engage in an action, such as a protest, that directly exposes a problem, or a possible solution to a contractual and/or societal issue. Union members engage in such actions to spotlight an injustice with the goal of correcting it. It further mobilizes the membership to work in concerted fashion for their own good and improvement. ACCRETION – The addition or consolidation of new employees or a new bargaining unit to or with an existing bargaining unit. ACROSS THE BOARD INCREASE - A general wage increase that covers all the members of a bargaining unit, regardless of classification, grade or step level. Such an increase may be in terms of a percentage or dollar amount. ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE – An agent of the National Labor Relations Board or the public sector commission appointed to docket, hear, settle and decide unfair labor practice cases nationwide or statewide in the public sector. They also conduct and preside over formal hearings/trials on an unfair labor practice complaint or a representation case. AFL-CIO - The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations is the national federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of fifty-six national and international unions, together representing more than 12 million active and retired workers. -

Introduction Darlington, RR

Introduction Darlington, RR Title Introduction Authors Darlington, RR Type Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/17902/ Published Date 2008 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Introduction Introduction During the first two decades of the twentieth century, amidst an extraordinary international upsurge in strike action, the ideas of revolutionary syndicalism connected with and helped to produce mass workers’ movements in a number of different countries across the world. An increasing number of syndicalist unions, committed to destroying capitalism through direct industrial action and revolutionary trade union struggle, were to emerge as either existing unions were won over to syndicalist principles in whole or in part, or new alternative revolutionary unions and organizations were formed by dissidents who broke away from their mainstream reformist adversaries. This international movement experienced its greatest vitality in the period immediately preceding and following the First World War, from about 1910 until the early 1920s (although the movement in Spain crested later). Amongst the largest and most famous unions influenced by syndicalist ideas and practice were the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) in France, the Confederación Nacional de Trabajo (CNT) in Spain, and the Unione Sindacale Italiana (USI) in Italy. -

Copyright I L L Ton Lawii Far Her

Copyright ill ton Lawii Far her, Jr. 1?59 I CHANGING ATTI1UDBB OP THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF LABOR TOWARD BUSINESS AID OOVSUBBMT 1929-1933 DBSBtTATIOS Rnmitod In Partial JhlflUaant of tho Raqulraaanta for tha Dacr«o Dootor of fhiloaephy In tha fraduats flehool of tha Ohio Stata UnivsrsHy By MILTON I S I S FARBBRf J R ., B. A ., M. A. Tha Ohio Stata Unlraraity 1959 Jppro*ad by Dapartaant of History ACKNMUSDGSMSra In tha preparation of thle dissertation* the author has incurred manor debts* to Hr. Jeorge Hsany for permission to use the Minutes of the AFL Executive Council; to Mrs. Eloise Ciles and her staff at the AFL-CIO librarj; to Hr. laroel Pittat of tha State Historical Society of VUsoonsin; to the staff of the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress; to Mrs. Wanda Rife, Miss Jans Catliff and Miss Hazel Johnson of the Ohio State University library; and to frofessor Alma Hsrbst of the Economics Department of the Ohio State University for her many kindnesses. The award of a William (keen Fellowship by the Ohio State University made possible the completion of this dissertation, lastly , the author acknowledges with gratitude the p ersisten t In terest and c r itic a l insight of Professor Foster Rhea Dulles which proved Invaluable throughout the preparation of the work. i i TAB IS OF CONTENTS Chapter Pag* I . GROANIZED LABOR ON THE EVE OF TUB DEPRESSION........................... 1 H . IKS SLA OF PERSUASION AND THE IEQACI OF QONPTOS.......................... 33 III* LABOR AND THE CRASH* 1929-30 * . • . ..................... 63 IV. -

The Taft-Hartley Act and Collective Bargaining, 9 Md

Maryland Law Review Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 2 The aT ft-Hartley Act and Collective Bargaining Jerome S. Wohlmuth Rhoda P. Krupka Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Jerome S. Wohlmuth, & Rhoda P. Krupka, The Taft-Hartley Act and Collective Bargaining, 9 Md. L. Rev. 1 (1948) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol9/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maryland Law Review VOLUME IX WINTR, 1948 NUMB3R 1 THE TAFF.HARTLEY ACT AND COLLECTIVE BARGAINING By JEROME S. WoHLmuTH,* and RHODA P. KRUPKA** INTRODUCTION. The Labor-Management Relations Act of 1947,1 more popularly known as the Taft-Hartley Act became law on June 23, 1947. It represents a sweeping departure from the philosophy of the Wagner Act,2 which it amends. The latter Act was conceived on the principle that the basic cause of industrial disputes stemmed from the inequality of bargaining power between employees who do not possess full freedom of association or actual liberty of contract and employers who fail to recognize and bargain with the representatives of the majority of their employees. There- fore, the Wagner Act proscribed various familiar unfair labor practices of employers and provided an easily acces- sible and simple election system to prove a union's majority in an appropriate bargaining unit to the end that free col- lective bargaining might take place over the terms and conditions of employment. -

Union Security and the Taft-Hartley Act Erwin S

;uke Iau JIournat VOLUME 1961 AUTUMN NUMBER 4 UNION SECURITY AND THE TAFT-HARTLEY ACT ERWIN S. MAYER* N analyzing the law of labor relations, it is useful to regard it as gov- erning a tripartite, private relation between employers, employees, and unions. The federal labor legislation of the two decades prior to 1947 consisted largely of a set of restraints placed on employers in their rela- tions especially with unions. One may view the union-security pro- visions of the Taft-Hartley Act' as an attempt to place parallel restraints on unions in their relations with employers and with employees. But whereas in the former case the law essentially regarded the union as an aggregate or extension of its members, in the latter case, the law may be said to have taken cognizance of the fact that the union exists as a separate entity with interests that may not always be consistent with those of actual or potential members. While it is dear that the Taft-Hartley Act has placed a number of other restrictions upon unions, this particular restraint appears to have been of greatest moment to them, if one may judge from the volume of comment they have lavished on the union-security provisions of the law in their official publications. It is the purpose of this article to assemble and to evaluate the objections unions have raised against the union-security provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act.2 *A.B. 1949, Hunter College5 Ph.D. 1956, University of Washington; Chairman, Department of Economics, Business and Government, Western Washington College. -

The Trade Union Unity League: American Communists and The

LaborHistory, Vol. 42, No. 2, 2001 TheTrade Union Unity League: American Communists and the Transitionto Industrial Unionism:1928± 1934* EDWARDP. JOHANNINGSMEIER The organization knownas the Trade UnionUnity League(TUUL) came intoformal existenceat anAugust 1929 conferenceof Communists and radical unionistsin Cleveland.The TUUL’s purposewas to create and nourish openly Communist-led unionsthat wereto be independent of the American Federation ofLabor in industries suchas mining, textile, steeland auto. When the TUUL was created, a numberof the CommunistParty’ s mostexperienced activists weresuspicious of the sectarian logic inherentin theTUUL’ s program. In Moscow,where the creation ofnew unions had beendebated by theCommunists the previous year, someAmericans— working within their establishedAFL unions—had argued furiously against its creation,loudly ac- cusingits promoters ofneedless schism. The controversyeven emerged openly for a time in theCommunist press in theUnited States. In 1934, after ve years ofaggressive butmostly unproductiveorganizing, theTUUL was formally dissolved.After the Comintern’s formal inauguration ofthe Popular Front in 1935 many ofthe same organizers whohad workedin theobscure and ephemeral TUULunions aided in the organization ofthe enduring industrial unionsof the CIO. 1 Historiansof American labor andradicalism have had difculty detectingany legitimate rationale for thefounding of theTUUL. Its ve years ofexistence during the rst years ofthe Depression have oftenbeen dismissed as an interlude of hopeless sectarianism, -

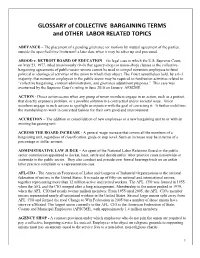

GLOSSARY of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING TERMS and OTHER LABOR RELATED TOPICS

GLOSSARY of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING TERMS and OTHER LABOR RELATED TOPICS ABEYANCE – The placement of a pending grievance (or motion) by mutual agreement of the parties, outside the specified time limits until a later date when it may be taken up and processed. ABOOD v. DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION – The legal case in which the U.S. Supreme Court, on May 23, 1977, ruled unanimously (9–0) that agency-shop (or union-shop) clauses in the collective- bargaining agreements of public-sector unions cannot be used to compel nonunion employees to fund political or ideological activities of the union to which they object. The Court nevertheless held, by a 6–3 majority, that nonunion employees in the public sector may be required to fund union activities related to “collective bargaining, contract administration, and grievance adjustment purposes.” This case was overturned by the Supreme Court’s ruling in June 2018 on Janus v. AFSCME. ACTION - Direct action occurs when any group of union members engage in an action, such as a protest, that directly exposes a problem, or a possible solution to a contractual and/or societal issue. Union members engage in such actions to spotlight an injustice with the goal of correcting it. It further mobilizes the membership to work in concerted fashion for their own good and improvement. ACCRETION – The addition or consolidation of new employees or a new bargaining unit to or with an existing bargaining unit. ACROSS THE BOARD INCREASE - A general wage increase that covers all the members of a bargaining unit, regardless of classification, grade or step level. -

Revolutionary Industrial Unionism 1900-1925 Larry Peterson

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 22:51 Labour/Le Travailleur The One Big Union in International Perspective Revolutionary Industrial Unionism 1900-1925 Larry Peterson Volume 7, 1981 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/llt7art02 Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Canadian Committee on Labour History ISSN 0700-3862 (imprimé) 1911-4842 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Peterson, L. (1981). The One Big Union in International Perspective: Revolutionary Industrial Unionism 1900-1925. Labour/Le Travailleur, 7, 41–66. All rights reserved © Canadian Committee on Labour History, 1981 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ The One Big Union in International Perspective: Revolutionary Industrial Unionism 1900-1925 Larry Peterson DURING THE FIRST decades of the twentieth century, workers in the advanced industrial nations attempted for the first time to organize themselves into industrial unions. Antecedents of modem industrial unionism date to the latter nineteenth century, when workers began to respond to the second wave of industrialization, but the movement to reorganize the labour-union movement along industrial lines did not become general until after the turn of the century. -

Interracial Unionism in the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union and the Development of Black Labor Organizations, 1933-1940

THEY SAW THEMSELVES AS WORKERS: INTERRACIAL UNIONISM IN THE INTERNATIONAL LADIES’ GARMENT WORKERS’ UNION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF BLACK LABOR ORGANIZATIONS, 1933-1940 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Julia J. Oestreich August, 2011 Doctoral Advisory Committee Members: Bettye Collier-Thomas, Committee Chair, Department of History Kenneth Kusmer, Department of History Michael Alexander, Department of Religious Studies, University of California, Riverside Annelise Orleck, Department of History, Dartmouth College ABSTRACT “They Saw Themselves as Workers” explores the development of black membership in the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) in the wake of the “Uprising of the 30,000” garment strike of 1933-34, as well as the establishment of independent black labor or labor-related organizations during the mid-late 1930s. The locus for the growth of black ILGWU membership was Harlem, where there were branches of Local 22, one of the largest and the most diverse ILGWU local. Harlem was also where the Negro Labor Committee (NLC) was established by Frank Crosswaith, a leading black socialist and ILGWU organizer. I provide some background, but concentrate on the aftermath of the marked increase in black membership in the ILGWU during the 1933-34 garment uprising and end in 1940, when blacks confirmed their support of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and when the labor-oriented National Negro Congress (NNC) was irrevocably split by struggles over communist influence. By that time, the NLC was also struggling, due to both a lack of support from trade unions and friendly organizations, as well as the fact that the Committee was constrained by the political views and personal grudges of its founder. -

No. 25, July 20, 1973

WfJRNERS ''1N(JIJI1RIJ 251 No. 25 .. :~~~ X·523 20 July 1973 Labor Tops SellOut to Nixon as ... oom eaos owar ust Coming in the midst of the Water dying social order already at an ad ficial of the HarriS Bank and Trust of form of money and debt claims-neither gate scandal which is daily exposing the vanced s tag e of decomposition, the Chicago as saying, "This is the un of which are very secure these days, slime of capitalist politics for all to bourgeoisie requires not scientific happiest boom I've ever lived through." Faced with the disaster of economic see, Nixon's "Phase Four" is one more analysis, but illUSions. The economic Indeed, the boom has generated the "normalization" in Phase Three, the proof of the bankruptcy of bourgeois "analysis" of the bourgeoisie is mere highest peacetime inflation since the Nixon administration has a g a i n re rule. Following a wave of price in wishful thinking-alternating with panic nineteenth century, while unemploy sorted to a hard line in state wage /price creases which have raised food costs when the facade of prosperity begins to ment remains high at 5 percent, and controls. Whatever the temporary ef by 47 percent in the last year, Nixon's crumble. that figure is sure to get worse. De fect on Nixon's sagging popularity rat 60-day price freeze (announced on 13 spite inflation and the high profit levels, ings, Phase Four will not provide a June) will simply be the prelude to a From Idiot Optimism to Despair the capitalists seem to find profit rates long-run solution to galloping inflation new round of inflation. -

Syndicalism's Legacy and Left Labor Strategy Today

Syndicalism’s Legacy and Left Labor Strategy Today In Western Europe, revolutionary syndicalism … was the direct and inevitable result of opportunism, reformism, and parliamentary cretinism (in the socialist movement). —Lenin Between the 1848 publication of the Communist Manifesto and the beginning of the twentieth century, socialists achieved mass working-class influence in the rich countries by building allied unions and political parties. But in the first two decades of the twentieth century, dissident revolutionaries built a rival tradition—the syndicalist movement. “Syndicalism,” an alternative term for “unionism,” reacted against the growing bureaucratic conservatism (and sometimes betrayals) of the socialist organizations. It stood for class struggle, direct action, workers’ control, rank and file democracy, internationalism, and revolution. Believing that working-class gains up to and including revolution required unionization as their weapon and striking (up to the general strike) as their tactic, syndicalists rejected political parties as worse than useless. This fit nicely for anarchists, whose influence resurged as “anarcho-syndicalism.” For others, syndicalism aligned with a return to the core Marxist concepts of working-class self-activity and self-emancipation. Syndicalist union federations prospered in Mexico, Ireland, Italy, Spain, and France. Though the movement was devastated by repression, fascism, and co-optation after World War I, much of its cadre joined the Communist International after grassroots workers’ democracy rose to insurrectionary success in Russia. As Communists, these ex-syndicalists accepted a reformulated role for working-class politics. But from their syndicalist experience they also forged for the International a theory of revolutionary union strategy—prioritizing independent rank and file organization—that was more sophisticated than anything previously developed by Marxists.