Calculous Disease of the Vermiform Appendix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mouth Esophagus Stomach Rectum and Anus Large Intestine Small

1 Liver The liver produces bile, which aids in digestion of fats through a dissolving process known as emulsification. In this process, bile secreted into the small intestine 4 combines with large drops of liquid fat to form Healthy tiny molecular-sized spheres. Within these spheres (micelles), pancreatic enzymes can break down fat (triglycerides) into free fatty acids. Pancreas Digestion The pancreas not only regulates blood glucose 2 levels through production of insulin, but it also manufactures enzymes necessary to break complex The digestive system consists of a long tube (alimen- 5 carbohydrates down into simple sugars (sucrases), tary canal) that varies in shape and purpose as it winds proteins into individual amino acids (proteases), and its way through the body from the mouth to the anus fats into free fatty acids (lipase). These enzymes are (see diagram). The size and shape of the digestive tract secreted into the small intestine. varies in each individual (e.g., age, size, gender, and disease state). The upper part of the GI tract includes the mouth, throat (pharynx), esophagus, and stomach. The lower Gallbladder part includes the small intestine, large intestine, The gallbladder stores bile produced in the liver appendix, and rectum. While not part of the alimentary 6 and releases it into the duodenum in varying canal, the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are all organs concentrations. that are vital to healthy digestion. 3 Small Intestine Mouth Within the small intestine, millions of tiny finger-like When food enters the mouth, chewing breaks it 4 protrusions called villi, which are covered in hair-like down and mixes it with saliva, thus beginning the first 5 protrusions called microvilli, aid in absorption of of many steps in the digestive process. -

Acute Onset Flank Pain-Suspicion of Stone Disease (Urolithiasis)

Date of origin: 1995 Last review date: 2015 American College of Radiology ® ACR Appropriateness Criteria Clinical Condition: Acute Onset Flank Pain—Suspicion of Stone Disease (Urolithiasis) Variant 1: Suspicion of stone disease. Radiologic Procedure Rating Comments RRL* CT abdomen and pelvis without IV 8 Reduced-dose techniques are preferred. contrast ☢☢☢ This procedure is indicated if CT without contrast does not explain pain or reveals CT abdomen and pelvis without and with 6 an abnormality that should be further IV contrast ☢☢☢☢ assessed with contrast (eg, stone versus phleboliths). US color Doppler kidneys and bladder 6 O retroperitoneal Radiography intravenous urography 4 ☢☢☢ MRI abdomen and pelvis without IV 4 MR urography. O contrast MRI abdomen and pelvis without and with 4 MR urography. O IV contrast This procedure can be performed with US X-ray abdomen and pelvis (KUB) 3 as an alternative to NCCT. ☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast 2 ☢☢☢ *Relative Rating Scale: 1,2,3 Usually not appropriate; 4,5,6 May be appropriate; 7,8,9 Usually appropriate Radiation Level Variant 2: Recurrent symptoms of stone disease. Radiologic Procedure Rating Comments RRL* CT abdomen and pelvis without IV 7 Reduced-dose techniques are preferred. contrast ☢☢☢ This procedure is indicated in an emergent setting for acute management to evaluate for hydronephrosis. For planning and US color Doppler kidneys and bladder 7 intervention, US is generally not adequate O retroperitoneal and CT is complementary as CT more accurately characterizes stone size and location. This procedure is indicated if CT without contrast does not explain pain or reveals CT abdomen and pelvis without and with 6 an abnormality that should be further IV contrast ☢☢☢☢ assessed with contrast (eg, stone versus phleboliths). -

Multiple Epithelia Are Required to Develop Teeth Deep Inside the Pharynx

Multiple epithelia are required to develop teeth deep inside the pharynx Veronika Oralováa,1, Joana Teixeira Rosaa,2, Daria Larionovaa, P. Eckhard Wittena, and Ann Huysseunea,3 aResearch Group Evolutionary Developmental Biology, Biology Department, Ghent University, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium Edited by Irma Thesleff, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, and approved April 1, 2020 (received for review January 7, 2020) To explain the evolutionary origin of vertebrate teeth from closure of the gill slits (15). Consequently, previous studies have odontodes, it has been proposed that competent epithelium spread stressed the importance of gill slits for pharyngeal tooth formation into the oropharyngeal cavity via the mouth and other possible (12, 13). channels such as the gill slits [Huysseune et al., 2009, J. Anat. 214, Gill slits arise in areas where ectoderm meets endoderm. In 465–476]. Whether tooth formation deep inside the pharynx in ex- vertebrates, the endodermal epithelium of the developing pharynx tant vertebrates continues to require external epithelia has not produces a series of bilateral outpocketings, called pharyngeal been addressed so far. Using zebrafish we have previously demon- pouches, that eventually contact the skin ectoderm at corre- strated that cells derived from the periderm penetrate the oropha- sponding clefts (16). In primary aquatic osteichthyans, most ryngeal cavity via the mouth and via the endodermal pouches and pouch–cleft contacts eventually break through to create openings, connect to periderm-like cells that subsequently cover the entire or gill slits (17–19). In teleost fishes, such as the zebrafish, six endoderm-derived pharyngeal epithelium [Rosa et al., 2019, Sci. -

Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 3 Print Reference: Pages 335-342 Article 30 1994 Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix Frank Maas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Maas, Frank (1994) "Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 3 , Article 30. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol3/iss1/30 IMMUNE FUNCTIONS OF THE VERMIFORM APPENDIX FRANK MAAS, M.S. 320 7TH STREET GERVAIS, OR 97026 KEYWORDS Mucosal immunology, gut-associated lymphoid tissues. immunocompetence, appendix (human and rabbit), appendectomy, neoplasm, vestigial organs. ABSTRACT The vermiform appendix Is purported to be the classic example of a vestigial organ, yet for nearly a century it has been known to be a specialized organ highly infiltrated with lymphoid tissue. This lymphoid tissue may help protect against local gut infections. As the vertebrate taxonomic scale increases, the lymphoid tissue of the large bowel tends to be concentrated In a specific region of the gut: the cecal apex or vermiform appendix. -

Appendicitis

Appendicitis National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse The appendix is a small, tube-like structure abdomen. Anyone can get appendicitis, attached to the first part of the large intes- but it occurs most often between the ages tine, also called the colon. The appendix of 10 and 30. is located in the lower right portion of National Institute of the abdomen. It has no known function. Diabetes and Removal of the appendix appears to cause Causes Digestive The cause of appendicitis relates to block- and Kidney no change in digestive function. Diseases age of the inside of the appendix, known Appendicitis is an inflammation of the as the lumen. The blockage leads to NATIONAL INSTITUTES appendix. Once it starts, there is no effec- increased pressure, impaired blood flow, OF HEALTH tive medical therapy, so appendicitis is and inflammation. If the blockage is not considered a medical emergency. When treated, gangrene and rupture (breaking treated promptly, most patients recover or tearing) of the appendix can result. without difficulty. If treatment is delayed, the appendix can burst, causing infection Most commonly, feces blocks the inside and even death. Appendicitis is the most of the appendix. Also, bacterial or viral common acute surgical emergency of the infections in the digestive tract can lead to Inflamed appendix Small intestine Appendix Large intestine U.S. Department The appendix is a small, tube-like structure attached to the first part of the large intestine, also called the colon. The of Health and appendix is located in the lower right portion of the abdomen, near where the small intestine attaches to the large Human Services intestine. -

Study of Calculus Pancreatitis

STUDY OF CALCULUS PANCREATITIS Dissertation Submitted for MS Degree (Branch I) General Surgery April 2011 The Tamilnadu Dr.M.G.R.Medical University Chennai – 600 032. MADURAI MEDICAL COLLEGE, MADURAI. CERTIFICATE This is to certify that this dissertation titled “STUDY OF CALCULUS PANCREATITIS” submitted by DR.P.K.PRABU to the faculty of General Surgery, The Tamilnadu Dr. M.G.R. Medical University, Chennai in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of MS degree Branch I General Surgery, is a bonafide research work carried out by him under our direct supervision and guidance from October 2008 to October 2010. DR. M.GOPINATH, M.S., Pro. A.SANKARAMAHALINGAM M.S, PROFESSOR AND HEAD, PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL SURGERY, DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL SURGERY, MADURAI MEDICAL COLLEGE, MADURAI MEDICAL COLLEGE, MADURAI. MADURAI. DECLARATION I, DR.P.K.PRABU solemnly declare that the dissertation titled “STUDY OF CALCULUS PANCREATITIS” has been prepared by me. This is submitted to The Tamilnadu Dr. M.G.R. Medical University, Chennai, in partial fulfillment of the regulations for the award of MS degree (Branch I) General Surgery. Place: Madurai DR. P.K.PRABU Date: ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the very outset I would like to thank Dr.A.EDWIN JOE M.D.,(FM) the Dean Madurai Medical College and Dr.S.M.SIVAKUMAR M.S., (General Surgery) Medical Superintendent, Government Rajaji Hospital, Madurai for permitting me to carryout this study in this Hospital. I wish to express my sincere thanks to my Head of the Department of Surgery Prof.Dr.M.GOPINATH M.S., and Prof.Dr.MUTHUKRISHNAN M.Ch., Head of the Department of Surgical Gastroenterology for his unstinted encouragement and valuable guidance during this study. -

Reflux Esophagitis

Reflux Esophagitis KEY FACTS TERMINOLOGY • Caustic esophagitis • Inflammation of esophageal mucosa due to PATHOLOGY gastroesophageal (GE) reflux • Lower esophageal sphincter: Decreased tone leads to IMAGING increased reflux • Irregular ulcerated mucosa of distal esophagus • Hydrochloric acid and pepsin: Synergistic effect • Foreshortening of esophagus: Due to muscle spasm CLINICAL ISSUES • Inflammatory esophagogastric polyps: Smooth, ovoid • 15-20% of Americans commonly have heartburn due to elevations reflux; ~ 30% fail to respond to standard-dose medical • Hiatal hernia in > 95% of patients with stricture therapy ○ Probably is result, not cause, of reflux ○ Prevalence of GE reflux disease has increased sharply • Peptic stricture (1- to 4-cm length): Concentric, smooth, with obesity epidemic tapered narrowing of distal esophagus • Symptoms: Heartburn, regurgitation, angina-like pain TOP DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES ○ Dysphagia, odynophagia • Scleroderma • Confirmatory testing: Manometric/ambulatory pH- monitoring techniques • Drug-induced esophagitis ○ Endoscopy, biopsy • Infectious esophagitis Imaging in Gastrointestinal Disorders: Diagnoses • Eosinophilic esophagitis (Left) Graphic shows a small type 1 (sliding) hiatal hernia ſt linked with foreshortening of the esophagus, ulceration of the mucosa, and a tapered stricture of distal esophagus. (Right) Spot film from an esophagram shows a small hiatal hernia with gastric folds ſt extending above the diaphragm. The esophagus appears shortened, presumably due to spasm of its longitudinal muscles. A stricture is present at the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, and persistent collections of barium indicate mucosal ulceration. (Left) Prone film from an esophagram shows a tight stricture ſt just above the GE junction with upstream dilation of the esophagus. The herniated stomach is pulled taut as a result of the foreshortening of the esophagus, a common and important sign of reflux esophagitis. -

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism I. MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION A. MUSCLES OF INHALATION (muscles that enlarge the thoracic cavity) 1. Diaphragm Attachments: The diaphragm originates in a number of places: the lower tip of the sternum; the first 3 or 4 lumbar vertebrae and the lower borders and inner surfaces of the cartilages of ribs 7 - 12. All fibers insert into a central tendon (aponeurosis of the diaphragm). Function: Contraction of the diaphragm draws the central tendon down and forward, which enlarges the thoracic cavity vertically. It can also elevate to some extent the lower ribs. The diaphragm separates the thoracic and the abdominal cavities. 2. External Intercostals Attachments: The external intercostals run from the lip on the lower border of each rib inferiorly and medially to the upper border of the rib immediately below. Function: These muscles may have several functions. They serve to strengthen the thoracic wall so that it doesn't bulge between the ribs. They provide a checking action to counteract relaxation pressure. Because of the direction of attachment of their fibers, the external intercostals can raise the thoracic cage for inhalation. 3. Pectoralis Major Attachments: This muscle attaches on the anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle, the sternum and costal cartilages 1-6 or 7. All fibers come together and insert at the greater tubercle of the humerus. Function: Pectoralis major is primarily an abductor of the arm. It can, however, serve as a supplemental (or compensatory) muscle of inhalation, raising the rib cage and sternum. (In other words, breathing by raising and lowering the arms!) It is mentioned here chiefly because it is encountered in the dissection. -

Postoperative Intrahepatic Calculus: the Role of Extracorporeal Shockwave Lithotripsy

Published online: 2021-04-10 Case Report Postoperative Intrahepatic Calculus: The Role of Extracorporeal Shockwave Lithotripsy Abstract Asad Irfanullah, Bile duct stones are a known complication after a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Different minimally Kamran Masood, invasive stone extraction techniques, including endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with Yousuf Memon, basket removal or the use of a choledocoscope through a mature T-tube tract, can be used. However, in some cases, they are unsuccessful due to complicated postsurgical anatomy or technical difficulty. Zakariya Irfanullah In this report, we present a case where extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy was used in conjunction Department of Radiology, Indus with standard interventional techniques to treat bile duct stones. Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan Keywords: Biliary tract calculus, extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy, post‑Roux‑en‑y hepaticojejunostomy Introduction medical history was significant for an open cholecystectomy complicated by Bile duct stones and anastomotic strictures iatrogenic injury to the common bile duct are known complications of Roux-en-y and subsequent creation of a Roux-en-y hepaticojejunostomy. Due to the postsurgical hepaticojejunostomy (REHJ). A magnetic anatomy, conventional endoscopic resonance cholangiopancreatography was retrograde cholangiopancreatography performed which demonstrated a significant (ERCP) techniques are often not possible. intrahepatic biliary dilatation with the In this specific case, we treated a large bile formation -

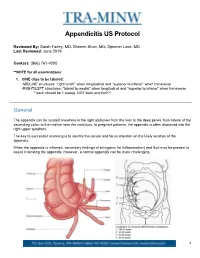

Appendicitis US Protocol

Appendicitis US Protocol Reviewed By: Sarah Farley, MD; Shireen Khan, MD; Spencer Lake, MD Last Reviewed: June 2019 Contact: (866) 761-4200 **NOTE for all examinations: 1. CINE clips to be labeled: -MIDLINE structures: “right to left” when longitudinal and “superior to inferior” when transverse -RIGHT/LEFT structures: “lateral to medial” when longitudinal and “superior to inferior” when transverse **each should be 1 sweep, NOT back and forth** General The appendix can be located anywhere in the right abdomen from the liver to the deep pelvis, from lateral of the ascending colon to the midline near the umbilicus. In pregnant patients, the appendix is often displaced into the right upper quadrant. The key to successful scanning is to identify the cecum and focus attention on the likely location of the appendix. When the appendix is inflamed, secondary findings of echogenic fat (inflammation) and fluid may be present to assist in locating the appendix. However, a normal appendix can be more challenging. 1 Strategies for finding the appendix include: 1. Review prior CT abdomen/pelvis or appendix US to see where appendix has been previously. 2. Scan in area of greatest pain (indicated by focal tenderness by 1 finger, not general pain). Label as such. 3. Localize cecum. 4. Localize ileocecal valve, if possible. Equipment: 1. Linear high frequency transducer is required, as this will best demonstrate anatomy of appendix. 2. In larger or obese patients, a curved lower frequency transducer may be used to obtain an overview and localize the cecum first. THEN, switch to the linear probe. a. When you locate the appendix, turn ON harmonics to better visualize the walls and appendiceal lumen together. -

Urinary Bladder – Calculus Urinary Bladder – Crystal

Urinary bladder – Calculus Urinary bladder – Crystal Figure Legend: Figure 1 A calculus (asterisk) fills the entire bladder lumen in a male F344/N rat from a chronic study. Figure 2 Hyperplasia of the urothelium (arrow) due to the presence of the calculus in a male F344/N rat from a chronic study. Figure 3 A small basophilic calculus (arrow) associated with chronic inflammation and urothelial hyperplasia in a female Harlan Sprague-Dawley rat from a chronic study. Comment: Calculi may be seen as spontaneous or as chemically induced lesions. Calculi may be single or multiple (Figure 1). Gross examination of the bladder is important since some small calculi may be washed out of the bladder when processed for histopathology. Calculi result from the precipitation of normal constituents or chemical compounds/metabolites associated with changes in urinary pH or other conditions. Frequently in the rodent, calculi contain some form of 1 Urinary bladder – Calculus Urinary bladder – Crystal calcium or mineral complex. Calculi often result in necrosis, ulceration, inflammation, and hyperplasia of the urothelium (Figure 2 and Figure 3). They are often the cause of bladder obstruction. In addition, bladder neoplasia may result from the presence of calculi. The presence of crystals and the subsequent appearance of calculi are often associated. Strain differences in the presence of crystals have been reported. Crystals, like calculi, tend to be washed out during histologic processing. Recommendation: Calculi and crystals should be diagnosed but should not be graded. Calculi are usually associated with secondary lesions, such as hemorrhage and inflammation. The pathologist should use his or her judgment in deciding whether or not these secondary lesions are prominent enough to warrant a separate diagnosis. -

Obstruction of the Urinary Tract 2567

Chapter 540 ◆ Obstruction of the Urinary Tract 2567 Table 540-1 Types and Causes of Urinary Tract Obstruction LOCATION CAUSE Infundibula Congenital Calculi Inflammatory (tuberculosis) Traumatic Postsurgical Neoplastic Renal pelvis Congenital (infundibulopelvic stenosis) Inflammatory (tuberculosis) Calculi Neoplasia (Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma) Ureteropelvic junction Congenital stenosis Chapter 540 Calculi Neoplasia Inflammatory Obstruction of the Postsurgical Traumatic Ureter Congenital obstructive megaureter Urinary Tract Midureteral structure Jack S. Elder Ureteral ectopia Ureterocele Retrocaval ureter Ureteral fibroepithelial polyps Most childhood obstructive lesions are congenital, although urinary Ureteral valves tract obstruction can be caused by trauma, neoplasia, calculi, inflam- Calculi matory processes, or surgical procedures. Obstructive lesions occur at Postsurgical any level from the urethral meatus to the calyceal infundibula (Table Extrinsic compression 540-1). The pathophysiologic effects of obstruction depend on its level, Neoplasia (neuroblastoma, lymphoma, and other retroperitoneal or pelvic the extent of involvement, the child’s age at onset, and whether it is tumors) acute or chronic. Inflammatory (Crohn disease, chronic granulomatous disease) ETIOLOGY Hematoma, urinoma Ureteral obstruction occurring early in fetal life results in renal dys- Lymphocele plasia, ranging from multicystic kidney, which is associated with ure- Retroperitoneal fibrosis teral or pelvic atresia (see Fig. 537-2 in Chapter 537), to various