Anatomy: Know Your Abdomen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anatomy of the Rectum and Anal Canal

BASIC SCIENCE identify the rectosigmoid junction with confidence at operation. The anatomy of the rectum The rectosigmoid junction usually lies approximately 6 cm below the level of the sacral promontory. Approached from the distal and anal canal end, however, as when performing a rigid or flexible sigmoid- oscopy, the rectosigmoid junction is seen to be 14e18 cm from Vishy Mahadevan the anal verge, and 18 cm is usually taken as the measurement for audit purposes. The rectum in the adult measures 10e14 cm in length. Abstract Diseases of the rectum and anal canal, both benign and malignant, Relationship of the peritoneum to the rectum account for a very large part of colorectal surgical practice in the UK. Unlike the transverse colon and sigmoid colon, the rectum lacks This article emphasizes the surgically-relevant aspects of the anatomy a mesentery (Figure 1). The posterior aspect of the rectum is thus of the rectum and anal canal. entirely free of a peritoneal covering. In this respect the rectum resembles the ascending and descending segments of the colon, Keywords Anal cushions; inferior hypogastric plexus; internal and and all of these segments may be therefore be spoken of as external anal sphincters; lymphatic drainage of rectum and anal canal; retroperitoneal. The precise relationship of the peritoneum to the mesorectum; perineum; rectal blood supply rectum is as follows: the upper third of the rectum is covered by peritoneum on its anterior and lateral surfaces; the middle third of the rectum is covered by peritoneum only on its anterior 1 The rectum is the direct continuation of the sigmoid colon and surface while the lower third of the rectum is below the level of commences in front of the body of the third sacral vertebra. -

Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents: to Do Or Not to Do?

children Review Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents: To Do or Not to Do? Valeria Calcaterra 1,2 , Hellas Cena 3,4 , Gloria Pelizzo 5,*, Debora Porri 3,4 , Corrado Regalbuto 6, Federica Vinci 6, Francesca Destro 5, Elettra Vestri 5, Elvira Verduci 2,7 , Alessandra Bosetti 2, Gianvincenzo Zuccotti 2,8 and Fatima Cody Stanford 9 1 Pediatric and Adolescent Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] 2 Pediatric Department, “V. Buzzi” Children’s Hospital, 20154 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (G.Z.) 3 Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics Service, Unit of Internal Medicine and Endocrinology, ICS Maugeri IRCCS, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (H.C.); [email protected] (D.P.) 4 Laboratory of Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition, Department of Public Health, Experimental and Forensic Medicine, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy 5 Pediatric Surgery Department, “V. Buzzi” Children’s Hospital, 20154 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (F.D.); [email protected] (E.V.) 6 Pediatric Unit, Fond. IRCCS Policlinico S. Matteo and University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (C.R.); [email protected] (F.V.) 7 Department of Health Sciences, University of Milan, 20146 Milan, Italy 8 “L. Sacco” Department of Biomedical and Clinical Science, University of Milan, 20146 Milan, Italy 9 Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Pediatric obesity is a multifaceted disease that can impact physical and mental health. -

The Subperitoneal Space and Peritoneal Cavity: Basic Concepts Harpreet K

ª The Author(s) 2015. This article is published with Abdom Imaging (2015) 40:2710–2722 Abdominal open access at Springerlink.com DOI: 10.1007/s00261-015-0429-5 Published online: 26 May 2015 Imaging The subperitoneal space and peritoneal cavity: basic concepts Harpreet K. Pannu,1 Michael Oliphant2 1Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065, USA 2Department of Radiology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA Abstract The peritoneum is analogous to the pleura which has a visceral layer covering lung and a parietal layer lining the The subperitoneal space and peritoneal cavity are two thoracic cavity. Similar to the pleural cavity, the peri- mutually exclusive spaces that are separated by the toneal cavity is visualized on imaging if it is abnormally peritoneum. Each is a single continuous space with in- distended by fluid, gas, or masses. terconnected regions. Disease can spread either within the subperitoneal space or within the peritoneal cavity to Location of the abdominal and pelvic organs distant sites in the abdomen and pelvis via these inter- connecting pathways. Disease can also cross the peri- There are two spaces in the abdomen and pelvis, the toneum to spread from the subperitoneal space to the peritoneal cavity (a potential space) and the subperi- peritoneal cavity or vice versa. toneal space, and these are separated by the peritoneum (Fig. 1). Regardless of the complexity of development in Key words: Subperitoneal space—Peritoneal the embryo, the subperitoneal space and the peritoneal cavity—Anatomy cavity remain separated from each other, and each re- mains a single continuous space (Figs. -

Rectum & Anal Canal

Rectum & Anal canal Dr Brijendra Singh Prof & Head Anatomy AIIMS Rishikesh 27/04/2019 EMBRYOLOGICAL basis – Nerve Supply of GUT •Origin: Foregut (endoderm) •Nerve supply: (Autonomic): Sympathetic Greater Splanchnic T5-T9 + Vagus – Coeliac trunk T12 •Origin: Midgut (endoderm) •Nerve supply: (Autonomic): Sympathetic Lesser Splanchnic T10 T11 + Vagus – Sup Mesenteric artery L1 •Origin: Hindgut (endoderm) •Nerve supply: (Autonomic): Sympathetic Least Splanchnic T12 L1 + Hypogastric S2S3S4 – Inferior Mesenteric Artery L3 •Origin :lower 1/3 of anal canal – ectoderm •Nerve Supply: Somatic (inferior rectal Nerves) Rectum •Straight – quadrupeds •Curved anteriorly – puborectalis levator ani •Part of large intestine – continuation of sigmoid colon , but lacks Mesentery , taeniae coli , sacculations & haustrations & appendices epiploicae. •Starts – S3 anorectal junction – ant to tip of coccyx – apex of prostate •12 cms – 5 inches - transverse slit •Ampulla – lower part Development •Mucosa above Houstons 3rd valve endoderm pre allantoic part of hind gut. •Mucosa below Houstons 3rd valve upto anal valves – endoderm from dorsal part of endodermal cloaca. •Musculature of rectum is derived from splanchnic mesoderm surrounding cloaca. •Proctodeum the surface ectoderm – muco- cutaneous junction. •Anal membrane disappears – and rectum communicates outside through anal canal. Location & peritoneal relations of Rectum S3 1 inch infront of coccyx Rectum • Beginning: continuation of sigmoid colon at S3. • Termination: continues as anal canal, • one inch below -

Autonomic Nerve Activity and Cardiac Arrhythmias

ACORP Complete (with appendices) Last Name of PI► Protocol No. Assigned by the IACUC►02002 Official Date of Approval► 1. Caging needs. Complete the table below to describe the housing that will have to be accommodated by the housing sites for this protocol: d. Is this housing e. Estimated c. Number of consistent with the maximum number a. Species b. Type of housing* individuals per Guide and USDA of housing units housing unit** regulations? needed at any one (yes/no***) time Chain link run, 3x6 Canines 1 no 7 and 4x10 feet cage *See ACORP Instructions, for guidance on describing the type of housing needed. If animals are to be housed according to a local Standard Operating Procedure (SOP), enter “standard (see SOP)” here, and enter the SOP into the table in Item Y. If the local standard housing is not described in a SOP, enter “standard, see below” in the table and describe the standard housing here: Chain link run, 3x6 feet cages ** The Guide states that social animals should generally be housed in stable pairs or groups. Provide a justification if any animals will be housed singly (if species is not considered “social”, then so note) Dogs are housed singly in chain link runs but can socialize with one another since each room has two to five dog runs. In addition, while their runs are being cleaned on a daily basis, pairs of dogs are allowed to exercise and play together in a designated "romper room". Animals are fitted with DSI transmitters and need to be housed singly in a cage for which DSI receivers are installed to receive signals from the transmitters. -

Mouth Esophagus Stomach Rectum and Anus Large Intestine Small

1 Liver The liver produces bile, which aids in digestion of fats through a dissolving process known as emulsification. In this process, bile secreted into the small intestine 4 combines with large drops of liquid fat to form Healthy tiny molecular-sized spheres. Within these spheres (micelles), pancreatic enzymes can break down fat (triglycerides) into free fatty acids. Pancreas Digestion The pancreas not only regulates blood glucose 2 levels through production of insulin, but it also manufactures enzymes necessary to break complex The digestive system consists of a long tube (alimen- 5 carbohydrates down into simple sugars (sucrases), tary canal) that varies in shape and purpose as it winds proteins into individual amino acids (proteases), and its way through the body from the mouth to the anus fats into free fatty acids (lipase). These enzymes are (see diagram). The size and shape of the digestive tract secreted into the small intestine. varies in each individual (e.g., age, size, gender, and disease state). The upper part of the GI tract includes the mouth, throat (pharynx), esophagus, and stomach. The lower Gallbladder part includes the small intestine, large intestine, The gallbladder stores bile produced in the liver appendix, and rectum. While not part of the alimentary 6 and releases it into the duodenum in varying canal, the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are all organs concentrations. that are vital to healthy digestion. 3 Small Intestine Mouth Within the small intestine, millions of tiny finger-like When food enters the mouth, chewing breaks it 4 protrusions called villi, which are covered in hair-like down and mixes it with saliva, thus beginning the first 5 protrusions called microvilli, aid in absorption of of many steps in the digestive process. -

48 Anal Canal

Anal Canal The rectum is a relatively straight continuation of the colon about 12 cm in length. Three internal transverse rectal valves (of Houston) occur in the distal rectum. Infoldings of the submucosa and the inner circular layer of the muscularis externa form these permanent sickle- shaped structures. The valves function in the separation of flatus from the developing fecal mass. The mucosa of the first part of the rectum is similar to that of the colon except that the intestinal glands are slightly longer and the lining epithelium is composed primarily of goblet cells. The distal 2 to 3 cm of the rectum forms the anal canal, which ends at the anus. Immediately proximal to the pectinate line, the intestinal glands become shorter and then disappear. At the pectinate line, the simple columnar intestinal epithelium makes an abrupt transition to noncornified stratified squamous epithelium. After a short transition, the noncornified stratified squamous epithelium becomes continuous with the keratinized stratified squamous epithelium of the skin at the level of the external anal sphincter. Beneath the epithelium of this region are simple tubular apocrine sweat glands, the circumanal glands. Proximal to the pectinate line, the mucosa of the anal canal forms large longitudinal folds called rectal columns (of Morgagni). The distal ends of the rectal columns are united by transverse mucosal folds, the anal valves. The recess above each valve forms a small anal sinus. It is at the level of the anal valves that the muscularis mucosae becomes discontinuous and then disappears. The submucosa of the anal canal contains numerous veins that form a large hemorrhoidal plexus. -

Multiple Epithelia Are Required to Develop Teeth Deep Inside the Pharynx

Multiple epithelia are required to develop teeth deep inside the pharynx Veronika Oralováa,1, Joana Teixeira Rosaa,2, Daria Larionovaa, P. Eckhard Wittena, and Ann Huysseunea,3 aResearch Group Evolutionary Developmental Biology, Biology Department, Ghent University, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium Edited by Irma Thesleff, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, and approved April 1, 2020 (received for review January 7, 2020) To explain the evolutionary origin of vertebrate teeth from closure of the gill slits (15). Consequently, previous studies have odontodes, it has been proposed that competent epithelium spread stressed the importance of gill slits for pharyngeal tooth formation into the oropharyngeal cavity via the mouth and other possible (12, 13). channels such as the gill slits [Huysseune et al., 2009, J. Anat. 214, Gill slits arise in areas where ectoderm meets endoderm. In 465–476]. Whether tooth formation deep inside the pharynx in ex- vertebrates, the endodermal epithelium of the developing pharynx tant vertebrates continues to require external epithelia has not produces a series of bilateral outpocketings, called pharyngeal been addressed so far. Using zebrafish we have previously demon- pouches, that eventually contact the skin ectoderm at corre- strated that cells derived from the periderm penetrate the oropha- sponding clefts (16). In primary aquatic osteichthyans, most ryngeal cavity via the mouth and via the endodermal pouches and pouch–cleft contacts eventually break through to create openings, connect to periderm-like cells that subsequently cover the entire or gill slits (17–19). In teleost fishes, such as the zebrafish, six endoderm-derived pharyngeal epithelium [Rosa et al., 2019, Sci. -

Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 3 Print Reference: Pages 335-342 Article 30 1994 Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix Frank Maas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Maas, Frank (1994) "Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 3 , Article 30. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol3/iss1/30 IMMUNE FUNCTIONS OF THE VERMIFORM APPENDIX FRANK MAAS, M.S. 320 7TH STREET GERVAIS, OR 97026 KEYWORDS Mucosal immunology, gut-associated lymphoid tissues. immunocompetence, appendix (human and rabbit), appendectomy, neoplasm, vestigial organs. ABSTRACT The vermiform appendix Is purported to be the classic example of a vestigial organ, yet for nearly a century it has been known to be a specialized organ highly infiltrated with lymphoid tissue. This lymphoid tissue may help protect against local gut infections. As the vertebrate taxonomic scale increases, the lymphoid tissue of the large bowel tends to be concentrated In a specific region of the gut: the cecal apex or vermiform appendix. -

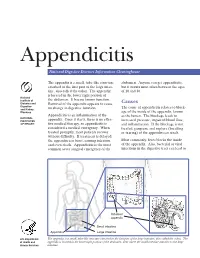

Appendicitis

Appendicitis National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse The appendix is a small, tube-like structure abdomen. Anyone can get appendicitis, attached to the first part of the large intes- but it occurs most often between the ages tine, also called the colon. The appendix of 10 and 30. is located in the lower right portion of National Institute of the abdomen. It has no known function. Diabetes and Removal of the appendix appears to cause Causes Digestive The cause of appendicitis relates to block- and Kidney no change in digestive function. Diseases age of the inside of the appendix, known Appendicitis is an inflammation of the as the lumen. The blockage leads to NATIONAL INSTITUTES appendix. Once it starts, there is no effec- increased pressure, impaired blood flow, OF HEALTH tive medical therapy, so appendicitis is and inflammation. If the blockage is not considered a medical emergency. When treated, gangrene and rupture (breaking treated promptly, most patients recover or tearing) of the appendix can result. without difficulty. If treatment is delayed, the appendix can burst, causing infection Most commonly, feces blocks the inside and even death. Appendicitis is the most of the appendix. Also, bacterial or viral common acute surgical emergency of the infections in the digestive tract can lead to Inflamed appendix Small intestine Appendix Large intestine U.S. Department The appendix is a small, tube-like structure attached to the first part of the large intestine, also called the colon. The of Health and appendix is located in the lower right portion of the abdomen, near where the small intestine attaches to the large Human Services intestine. -

The Digestive System

69 chapter four THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM The digestive system is structurally divided into two main parts: a long, winding tube that carries food through its length, and a series of supportive organs outside of the tube. The long tube is called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The GI tract extends from the mouth to the anus, and consists of the mouth, or oral cavity, the pharynx, the esophagus, the stomach, the small intestine, and the large intes- tine. It is here that the functions of mechanical digestion, chemical digestion, absorption of nutrients and water, and release of solid waste material take place. The supportive organs that lie outside the GI tract are known as accessory organs, and include the teeth, salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. Because most organs of the digestive system lie within body cavities, you will perform a dissection procedure that exposes the cavities before you begin identifying individual organs. You will also observe the cavities and their associated membranes before proceeding with your study of the digestive system. EXPOSING THE BODY CAVITIES should feel like the wall of a stretched balloon. With your skinned cat on its dorsal side, examine the cutting lines shown in Figure 4.1 and plan 2. Extend the cut laterally in both direc- out your dissection. Note that the numbers tions, roughly 4 inches, still working with indicate the sequence of the cutting procedure. your scissors. Cut in a curved pattern as Palpate the long, bony sternum and the softer, shown in Figure 4.1, which follows the cartilaginous xiphoid process to find the ventral contour of the diaphragm. -

Magnetic Resonance Enterography Findings of a Gastrocolic Fistula in Crohn’S Disease

Letter to the Editor Magnetic resonance enterography findings of a gastrocolic fistula in Crohn’s disease Sanne N. van Munster1, Mark F. J. Stolk2, Karel C. Kuypers3, Rene Wiezer1, Thomas L. Bollen4 1Department of Surgery, 2Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 3Department of Pathology, 4Department of Radiology, Sint Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands Correspondence to: Drs. Sanne N. van Munster. AMC, Academisch Medisch Centrum Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Email: [email protected]. Submitted Jul 09, 2016. Accepted for publication Jul 30, 2016. doi: 10.21037/qims.2016.08.06 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/qims.2016.08.06 Crohn’s disease (CD) is characterized by patches of Definitive treatment was established by segment inflammation, which may affect the whole gastro-intestinal resection of the splenic flexure with stapling of the tract. Internal fistulization is a common complication of CD gastrocolic fistula Figure( 1). The postoperative course was due to the transmural nature of inflammation. However, unremarkable and patient recovered uneventfully. gastrocolic fistulas are rare in CD. We present the magnetic Gross pathological examination of the surgical specimen resonance enterography (MRE) findings of a gastrocolic confirmed the presence of fistulous disease. A deep fistula in a patient with longstanding CD with clinical and penetrating inflammatory process originated from the pathologic correlation. colonic mucosa, extended through the colonic wall and attached to the stomach. In this inflammatory tract, gastric mucosa was found represented by glands formed by parietal Case presentation and chief cells of fundic mucosa. A 29-year-old woman with perianal fistulizing CD visited our hospital for left-sided upper abdominal pain starting Discussion about 30 minutes after the meals, bloating, diarrhea, anorexia, and weight loss.