Protecting Your Intellectual Property: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circular 1 Copyright Basics

CIRCULAR 1 Copyright Basics Copyright is a form of protection Copyright is a form of protection provided by the laws of the provided by U.S. law to authors of United States to the authors of “original works of authorship” that are fixed in a tangible form of expression. An original “original works of authorship” from work of authorship is a work that is independently created by the time the works are created in a a human author and possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity. A work is “fixed” when it is captured (either fixed form. This circular provides an by or under the authority of an author) in a sufficiently overview of basic facts about copyright permanent medium such that the work can be perceived, and copyright registration with the reproduced, or communicated for more than a short time. Copyright protection in the United States exists automatically U.S. Copyright Office. It covers from the moment the original work of authorship is fixed.1 • Works eligible for protection • Rights of copyright owners What Works Are Protected? • Who can claim copyright • Duration of copyright Examples of copyrightable works include • Literary works • Musical works, including any accompanying words • Dramatic works, including any accompanying music • Pantomimes and choreographic works • Pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works • Motion pictures and other audiovisual works • Sound recordings, which are works that result from the fixation of a series of musical, spoken, or other sounds • Architectural works These categories should be viewed broadly for the purpose of registering your work. For example, computer programs and certain “compilations” can be registered as “literary works”; maps and technical drawings can be registered as “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works.” w copyright.gov note: Before 1978, federal copyright was generally secured by publishing a work with an appro- priate copyright notice. -

Embedding a Copyright Into an Image One of the Main Concerns About Putting Images on the Web, Is the Theft of Those Images

Embedding A Copyright Into An Image One of the main concerns about putting images on the web, is the theft of those images. Putting your name in text on the image will not guarantee the safety of the image. The healing brush can easily remove text from an image. Photoshop offers a number of ways to embed your personal and copyright information in your image files. There is a bit of extra work involved in the copyright process and sometimes it can be visually intrusive. But, if the image is important to you, the time is worth it. There is also a more powerful option available via a plugin that is less visually intru- sive. This option is available though the Digimarc plugin which when chosen, takes you to the their web site. You can read more about it by going to http://www.digimarc. com. There is a yearly fee for using this option based on the number of images and options selected. Add Copyright Information to File Info 1. Open an image. 2. In the File menu, choose File Info... The File Info dialogue box appears. 3. Fill in all important information. Embedding TitleA Copyright goes here Into An Image Use a Font Copyright Symbol 1. Select the Type Tool. 2. In the Tools Option bar set options to: Helvetica Bold 500 pts - 3. Click the Type Palette icon if the Type Palette is not already open. 4. Use the option +g keys (mac), or Alt+g keys (windows) to type a copyright symbol 5. Move into position. -

Copyrights Quick Reference Series

Copyrights Quick Reference Series Designing a t-shirt? Showing a movie on campus? Creating a website? For these things and more it is important to understand the laws and rules surrounding copyrighted material. Check out the information below to understand how copyright affects your student org. Copyright Material In the United States Code, Title 17, Section 107 of the Copyright Law allows for the “fair use” of a copyrighted work for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research. The Fair Use Doctrine allows for limited use of copyrighted materials without obtaining permission from the copyright holder, but the limitations are significant. The factors to be considered in determining if the copying is fair use are: The purpose and character of the use (education is more likely to be fair use and use that causes the work to be used for a new purpose is more likely to be fair use) The nature of the copyrighted work (a fact-based work is more likely to be fair use than a creative fictional work) The amount and substantiality of the copied portion compared to the work as a whole (a small portion and/or not copying the “best” portion(s) of the work is more likely to be fair use) The effect of the use on the potential market (copying that does not cause someone to not buy the whole work is more likely to be fair use) Copyright and Trademark Symbols © is the copyright symbol and signifies a creator’s exclusive rights to publish, reproduce, or sell an original work. -

Use of Copyrighted/Trademarked Materials in 4-H Fair Exhibits And

For Staff and Judges Use of COPYRIGHTED/TRADEMARKED Material In 4-H Fair Exhibits and Activities What does copyright mean?????? A copyright and/or a trademark are legal methods used by artists, photographers, writers, and others to protect their original and creative works. Protected items may range from professional photography and books to music, sport logo insignias, corporate and brand name logos to art designs. It is important to remember the idea itself cannot receive a copyright. The expression of an idea is what is copyrighted. For example, one cannot copyright "bears", but specific bears like Winnie-the-Pooh and Smoky Bear cannot be copied without permission. As an educational agency, 4-H has the responsibility to prepare materials that help program participants learn about proper use of copyright and trademark regulations. Copyright means complete or portions of materials cannot be reproduced without permission and proper crediting of the source. It is not possible to address all situations that may occur; however, the following information will provide some background for making decisions and determining appropriate actions. Proper crediting of source includes name of book, magazine, newspaper, etc., author/artist/ publisher (which ever is most logical), date of publication, page number. If 4-H’ers lack some of the documentation when exhibiting, judges should use the situation as a teachable moment, remembering this is meant to be a learning experience not a policing experience. It is the responsibility of individual 4-H’ers to be aware of copyright/trademark regulations when developing 4-H exhibits and communication activities for county and state fairs. -

Microsoft Word Top Ten Tips

Microsoft Word Top Ten Tips 1. Normal/defaults 2. Quick Access Toolbar 3. AutoCorrect 4. Section symbol 5. AutoText/Quick Part Gallery 6. Insert Text from File 7. Suppress page number 8. Converting documents 9. Reveal Formatting 10. Resources Administrative Office Created by Lois McLeod, AO-DTS-SDSO-TD of the U.S. Courts June 2016 Normal/defaults To set the default font: 1. Launch the Font dialog box. 2. Choose the desired Font and Size. 3. Click Set As Default. 4. Click All documents based on the Normal.dotm template? and click OK. 2 #2 Quick Access Toolbar The Quick Access Toolbar (QAT) begins with only three tools: Save, Undo, and Redo. Here are two ways to add tools: 1. Click the More button ( ) at the right end of the QAT and select any listed tool desired. Click More Commands at the bottom of the QAT drop-down list to access All Commands and/or to rearrange the order of the tools on the QAT. 2. Right-click any tool on any ribbon and select Add to Quick Access Toolbar. 3 #3 AutoCorrect AutoCorrect enables you to create “abbreviations” for often-used text and/or corrections to incorrectly typed text. 1. On the File tab, click Options. 2. Click the Proofing tab. 3. Click AutoCorrect Options. 4. Click the AutoCorrect tab. 5. In the Replace box, enter the abbreviation (or misspelled/mistyped word to be corrected automatically). 6. In the With box, enter the replacement text. 7. Click Add. 8. To close the dialog boxes, click OK twice. As the abbreviation or incorrect form of the word is typed (followed by pressing the Spacebar, Tab or Enter), it is automatically replaced with the expanded version or correct spelling. -

Common Intellectual Property Abbreviations and Symbols

www.oliveandolive.com 500 Memorial Street • Post Office Box 2049 • Durham, NC 27702-2049 I Phone (919)683-5514 • Fax (919)683-3781 COMMON INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ABBREVIATIONS AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY SYMBOLS: The Meaning of Abbreviations and Symbols for Patents, Trademarks, Copyrights, Mask Works, and Designs Abbreviation or Meaning Symbol Patent or Pat. Indicates an invention protected by an issued United States patent. A proper patent notice contains one of these listed terms, followed by the patent number. Sometimes the letters “U.S.” are added before one of the terms, and sometimes the abbreviation “No.” or “Number” are used after one of the terms, but they are not required. The notice should appear either on the protected article or, if that is not possible, on a label affixed to it or to its packaging. For more information about patents, refer to our Learning Center article on Patents. Patent Pending or An application has been filed seeking to protect some aspect of the Pat. Pending marked invention. This designation does not mean a patent has issued. It may never issue. Reg. U.S. Pat. & Indicates a mark which has been registered with the United States TM Office or Patent & Trademark Office. The owner of such a mark has greater protection than do owners of unregistered marks. For more ® information about trademarks, refer to our Learning Center article on Trademarks, and our short article on appropriate trademark use. SM SM or Stands for “service mark” and means that someone is claiming the adjacent word or symbol as their trademark to identify the services, such as restaurant services, which they are offering. -

Former Cataloging Practices You May See in “Legacy” Records -- "Answers"

Descriptive Cataloging Using RDA: Former Cataloging Practices You May See in “Legacy” Records “Answers” With the implementation of RDA, some cataloging practices have changed. Just as during the earlier implementation of AACR2, the Library of Congress generally does not retrospectively revise records created using those rules; they were correct according to rules in force at the time. This document highlights some of the changes. The records below illustrate practices under the former cataloging rules; under each illustration is a brief reminder of the RDA practice. Generally, accept this data in existing records. If in doubt about the need to revise any such elements, consult your supervisor. When importing such records for Copy Cataloging, follow section practice and DCM B13 regarding what to revise. Cataloger-supplied abbreviations were used (some of them Latin-based) • s.l. for ‘sine loco’ when place of publication unknown • s.n. for ‘sine nomine’ when publisher unknown • n.d. for ‘no date’ when date of publication unknown • p. for ‘pages’ routinely abbreviated in 300 $a RDA Practice: Do not supply abbreviations; transcribe what you see; infer publication data How should these elements look according to RDA? The publication information should be recorded in a 264 #1. Rather than using Latin abbreviations, [Place of publication] and [publisher not identified] are supplied in separate sets of square brackets. Manufacturing data should appear in a separate 264 field without parentheses. Descriptive Cataloging Using RDA: Legacy (Answers) 1 February 2015 Bracketed data appeared more frequently in records RDA Practice: There is less need to bracket because more sources are valid How should these elements look according to RDA? The leaves of plates should be recorded without brackets (see examples in 3.4.5.9). -

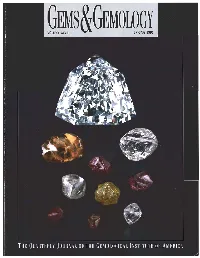

Spring 1991 Gems & Gemology

VOLUMEGEMS&GEMOLOGY XXVll SPRING 1991 SPRING 1991 Volume 27 No. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 The International Gemological Symposium: Facing the Future with GIA William E. Boyajian 2 Age, Origin, and Emplacement of Diamonds: Scientific Advances in the Last Decade Melissa B. IZirlzley, Iohn I. Gzlrney, and Alfred A. Levinson 26 Emeralds of the Panjshir Valley, Afghanistan Gary Bowersox, Lawrence W Snee, Eugene E. Foord, and Robert R. Seal II REGULARFEATURES 40 Gem Trade Lab Notes 46 Gem News 57 The Most Valuable Article Award and a New Look for Gems & Gemology I 59 Gems & Gemology Challenge - 61 Gemological Abstracts SPECIALSECTION: THE INTERNATIONAL GEMOLOGICALSYMPOSIUM Introduction 1 Abstracts of Feature Presentations 15 Panels and Panelists 17 Poster Session-A Marketplace of New Ideas ABOUT THE COVER: Diamonds are the heart of the jewelry industry Of critical importance is the continued supply of fine diamonds from the mines into the n~arlzetplace.The article on recenl research into the age, origin, and emplacement - of diamonds featured ~n this issue reviews new developments thul will be useful in the exploration and mining of diamonds for yeors to come. It cojncjdes with 1 the celebration of CIA'S diamond anniversary-60 years of service to the jewelry indrrstry In fi~tingtribute, this 89.01-ct D-internally flawless modified shield cut- the Guinea Star-sits above a group of fine rough diamonds that range from 0.74-12.76 ct. The faceted diamond is courtesy of William Goldberg Diamond Corp., New York; the other dicrmonds are courtesy of Cora Dinmond Corp., New York. Photo by Shone McClure. -

HTML Entities

HHTTMMLL EENNTTIITTIIEESS http://www.tutorialspoint.com/html/html_entities.htm Copyright © tutorialspoint.com Some characters are reserved in HTML and they have special meaning when used in HTML documemt. For example, you cannot use the greater than and less than signs or angle brackets within your HTML text because the browser will treat them differently and will try to draw a meaning related to HTML tag. HTML processors must support following five special characters listed in the table that follows. Symbol Description Entity Name Number Code " quotation mark " " ' apostrophe ' ' & ampersand & & < less-than < < > greater-than > > Example If you want to write <div > as a code then you will have to write as follows: <!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <title>HTML Entities</title> </head> <body> <div id="character"> </body> </html> This will produce following result: <div id="character"> There is also a long list of special characters in HTML 4.0. In order for these to appear in your document, you can use either the numerical codes or the entity names. For example, to insert a copyright symbol you can use either of the following: © 2007 or © 2007 ISO 8859-1 Symbol Entities Result Description Entity Name Number Code non-breaking space   ¡ inverted exclamation mark ¡ ¡ ¤ currency ¤ ¤ ¢ cent ¢ ¢ £ pound £ £ ¥ yen ¥ ¥ ¦ broken vertical bar ¦ ¦ § section § § ¨ spacing diaeresis ¨ ¨ © copyright -

Intellectual Property 101 Just the Faqs

Intellectual Property 101 Just the FAQs From the Intellectual Property Group What is IP? Intellectual Property (IP) can be anything from a particular manufacturing process to a company’s logo, a trade secret like a formula, or song lyrics. The formal definition, according to the World Intellectual Property Organization, is creations of the mind—inventions, literary and artistic works, symbols, names, images, and designs used in commerce. Unlike physical property, such as real estate, stocks or bonds, IP constitutes intangible personal property. IP rights protect your right to use your original creation, but does not protect the idea itself. Some IP rights last for a specific amount of time, while others can, in theory, last forever. What are the Different Types of IP? From a legal standpoint, there are four types of intellectual property: Patents: A patent is the right to utilize an invention and to allow others to use it as you choose, generally for 20 years. A patent is granted by the government in exchange for the inventor publicly disclosing the invention—in short, this means telling the world how to re-create the discovery so that other scientists and researchers can build upon it. After a patent term ends, anyone is free to utilize the invention. Examples of Patents: computer software, cosmetics, and machines. Trademarks: Trademarks enable the public to identify the source of goods or services. A trademark can be a word, picture, symbol, or other distinguishing mark, or even a sound or smell. These are the brand names of our favorite products. These brands allow us to identify competing products by quickly looking at their marks. -

Symbols.Indd

TECHNOLOGY Microsoft Office – WRITER MARIE Inserting Symbols and HERMAN Special Characters Marie Herman shares her tips on inserting special characters within Microsoft office Do you ever have to insert special characters fractions, etc. However, “non traditional” fonts combinations are intended for the numeric that aren’t on the keyboard? There are many with names like wingdings, dingbats, etc. will keypad on the right side of your keyboard, not options available for you in Microsoft Office to tend to show graphical images. the numbers along the top. make the job easier. • Shortcut Key • Special Characters Character Map (Insert – Symbol) The Shortcut Key allows you to assign a The second tab is Special Characters, which The first place to look for a special character is keyboard combination to that symbol, if there shows you a list of some of the most common on the Insert Ribbon, using the Symbol button. isn’t already one. How do you know if there symbols that people use every day and their The triangle next to Symbol shows you some of is one? Look to the right of the Shortcut Key keyboard shortcuts. This includes things like the most common and recently used characters button. If there is a shortcut key, it will show trademarks, curly quote marks, non-breaking in a drop down menu. The More Symbols there. Most keyboard shortcuts that you would characters, etc. button will bring up the character map built create are best done with the Alt button, as into Windows. most of the Ctrl button shortcuts are taken (i.e. -

Style Rules for Materials to Be Published by Actec

THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF TRUST AND ESTATE COUNSEL STYLE RULES FOR MATERIALS TO BE PUBLISHED BY ACTEC For authors who submit articles and outlines to ACTEC, these rules are guidelines, not rules - they are hoped to be a resource for their use. Revised Through October 8, 1994 STYLE RULES FOR MATERIALS TO BE PUBLISHED BY ACTEC TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE ARTICLE NUMBER NUMBER 1 GENERAL Manuscript Preparation 1.1 1 Furnishing Computer Text 1.2 1 Outline Numbering 1.3 1 (a) Lengthy Outlines 1.3(a) 1 (b) Less Extensive Outlines 1.3(b) 2 © Simple Outlines 1.3© 2 Margins 1.4 2 (a) In General 1.4(a) 2 (b) Top and Bottom 1.4(b) 2 © Left and Right 1.4© 3 Pagination 1.5 3 Table of Contents 1.6 3 Optional Bottom Line Footers 1.7 3 2 PUNCTUATION Commas 2.1 5 (a) In a Series 2.1(a) 5 (b) With a Conjunction 2.1(b) 5 Semicolons 2.2 5 (a) In Place of a Conjunction 2.2(a) 5 (b) In a Series 2.2(b) 5 Colons and Dashes 2.3 6 (a) Colons 2.3(a) 6 (b) Dashes 2.3(b) 6 Quotation Marks 2.4 7 (a) With Direct Quotes 2.4(a) 7 (b) For Emphasis 2.4(b) 7 © With Several Paragraphs 2.4© 8 Hyphens 2.5 8 (a) With Compound Adjectives 2.5(a) 8 (b) With Certain Compound Words 2.5(b) 8 © With Certain Prefixes 2.5© 8 (d) With Certain Terms and Abbreviations 2.5(d) 8 Apostrophes 2.6 9 (a) With Possessives 2.6(a) 9 (b) Not With Plural Abbreviations and Numbers 2.6(b) 9 © With an "Inner Quote" 2.6© 9 Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE ARTICLE NUMBER NUMBER 2 PUNCTUATION (continued) Brackets 2.7 9 (a) With an "Inner Parenthetical Phrase" 2.7(a) 9 (b) With Certain Citations 2.7(b)