Bushido in the Courtroom: a Case for Virtue-Oriented Lawyering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking the Connection of Metaphor and Commonplace

RETHINKING THE CONNECTION OF METAPHOR AND TOPOS MAREIKE BUSS & JÖRG JOST RWTH AACHEN 1. Introduction Having survived the «death of rhetoric» (R. BARTHES 1985: 115), metaphor has become the centre of intensive research by philosophers of language and linguists in the twentieth cen- tury. Nowadays it is widely accepted that metaphor is not reducible to «a sort of happy extra trick with words» (I. A. RICHARDS [1936] 1964: 90), but is rather said to be a funda- mental principle of linguistic creativity with an invaluable cognitive function and heuristic potential. Topos or rather commonplace has, in contrast, a predominantly negative connota- tion in everyday and scientific language. Topos, which originally designated the place where to find the arguments for a speech, has become the cliché, the worn out phrase, or the stereotype. Nevertheless, there are numerous critical studies focusing on topoi in their heu- ristic and argumentative function. Aristotle’s Art of Rhetoric is one of the first and most important ‘textbooks’ for speech production. Following Aristotle, the purpose of rhetorical speech consists in persuading by argumentation. In this respect he defines rhetoric as «the faculty of discovering the possible means of persuasion in reference to any subject whatever.» (Rhetoric I, 1355b/14,2). Now, persuasion presupposes – as any perlocutionary act – that the utterances have been under- stood by the audience, in short: it presupposes (text) comprehension.1 When analysing the first three phases of rhetoric – heuresis, taxis and lexis – two features in particular stand out on account of the role they play in argumentation: topos and metaphor, which are treated in the heuresis and the lexis.2 Metaphor works in a heuristic and aesthetic manner, while topos operates in a heu- ristic and logical manner. -

Virtue and Rights in American Property Law Eric R

Cornell Law Review Volume 94 Article 14 Issue 4 May 2009 Virtue and Rights in American Property Law Eric R. Claeys Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Eric R. Claeys, Virtue and Rights in American Property Law, 94 Cornell L. Rev. 889 (2009) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol94/iss4/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESPONSE VIRTUE AND RIGHTS IN AMERICAN PROPERTY LAW Eric R. Claey4 INTRODUCTION: ON VIRTUE AND FRYING PANS In Plato's Republic, Socrates persuades his conversationalists to help him construct a city organized around commerce. Glaucon, who has an idealist streak, dismisses this city as a "city of pigs."1 In re- sponse, Socrates sketches for Glaucon an ideal city ruled by the most virtuous citizens-the philosophers. 2 To make the city as just and har- monious as possible, the philosophers abolish the institution of pri- vate property. They require the auxiliary citizens to use external 3 assets only in cooperation, to contribute to common civic projects. This conversational thread presents a tension that is simply un- solvable in practical politics in any permanent way. Politics focuses to an important extent on low and uncontroversial ends, most of which are associated with comfortable self-preservation. -

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States Copyright 2006 Rob Redmond. All Rights Reserved. No part of this may be reproduced for for any purpose, commercial or non-profit, without the express, written permission of the author. Listed with the US Library of Congress US Copyright Office Registration #TXu-1-167-868 Published by digital means by Rob Redmond PO BOX 41 Holly Springs, GA 30142 Second Edition, 2006 2 Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States In Gratitude The Karate Widow, my beautiful and apparently endlessly patient wife – Lorna. Thanks, Kevin Hawley, for saying, “You’re a writer, so write!” Thanks to the man who opened my eyes to Karate other than Shotokan – Rob Alvelais. Thanks to the wise man who named me 24 Fighting Chickens and listens to me complain – Gerald Bush. Thanks to my training buddy – Bob Greico. Thanks to John Cheetham, for publishing my articles in Shotokan Karate Magazine. Thanks to Mark Groenewold, for support, encouragement, and for taking the forums off my hands. And also thanks to the original Secret Order of the ^v^, without whom this content would never have been compiled: Roberto A. Alvelais, Gerald H. Bush IV, Malcolm Diamond, Lester Ingber, Shawn Jefferson, Peter C. Jensen, Jon Keeling, Michael Lamertz, Sorin Lemnariu, Scott Lippacher, Roshan Mamarvar, David Manise, Rolland Mueller, Chris Parsons, Elmar Schmeisser, Steven K. Shapiro, Bradley Webb, George Weller, and George Winter. And thanks to the fans of 24FC who’ve been reading my work all of these years and for some reason keep coming back. -

Rethinking Mimesis

Rethinking Mimesis Rethinking Mimesis: Concepts and Practices of Literary Representation Edited by Saija Isomaa, Sari Kivistö, Pirjo Lyytikäinen, Sanna Nyqvist, Merja Polvinen and Riikka Rossi Rethinking Mimesis: Concepts and Practices of Literary Representation, Edited by Saija Isomaa, Sari Kivistö, Pirjo Lyytikäinen, Sanna Nyqvist, Merja Polvinen and Riikka Rossi Layout: Jari Käkelä This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Saija Isomaa, Sari Kivistö, Pirjo Lyytikäinen, Sanna Nyqvist, Merja Polvinen and Riikka Rossi and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3901-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3901-3 Table of ConTenTs Introduction: Rethinking Mimesis The Editors...........................................................................................vii I Concepts of Mimesis Aristotelian Mimesis between Theory and Practice Stephen Halliwell....................................................................................3 Rethinking Aristotle’s poiêtikê technê Humberto Brito.....................................................................................25 Paul Ricœur and -

The Naihanchi Enigma by Tim Shaw Web Version At

The Naihanchi Enigma by Tim Shaw Web version at: http://www.wadoryu.org.uk/naihanchi.html Introduction Naihanchi kata within Wado Ryu Within the Wado Ryu style of Japanese karate the kata Naihanchi holds a special place, positioned as it is as a gateway to the complexities of Seishan and Chinto. But as a gateway it presents its own mysteries and contradictions. Through Naihanchi Wado stylists are directed to study the subtleties of body movements and develop particular ways of generating energy found primarily in this kata. They are taught that the essence of this ancient Form is to be found in the stance and that the inherent principles are applied directly to the Wado Ryu Kumite (the pairs exercises) and to achieve a stage where these principles become part of the practitioners body and natural movements involves countless repetitions of this particular form. The following tantalizing quote from the founder of Wado Ryu Karate Hironori Ohtsuka, gives intriguing clues as to the value and influence that this particular kata holds. "Every technique (in Naihanchi) has its own purpose. I personally favour Naihanchi. It is not interesting to the eye, but it is extremely difficult to use. Naihanchi increases in difficulty with more time spent practicing it, however, there is something "deep" about it. It is fundamental to any move that requires reaction. Some people may call me foolish for my belief. However, I prefer this kata over all else and hence incorporate it into my movement."1 Many Wado karate-ka practice Naihanchi diligently, while remaining largely unaware of the background and long history of this unusual kata. -

Linguistic Patterns of Viewpoint Transfer in News Narratives

Cognitive Linguistics 2019; 30(3): 499–529 Kobie van Krieken* and José Sanders Smoothly moving through Mental Spaces: Linguistic patterns of viewpoint transfer in news narratives https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2018-0063 Received 1 June 2018; revised 18 December 2018; accepted 20 December 2018 Abstract: This article presents a Mental Space model for analyzing linguistic patterns in news narratives. The model was applied in a corpus study categoriz- ing various linguistic markers of viewpoint transfers between the mental spaces that readers must conceptualize while processing news narratives: a Reality Space representing the journalist and reader’s projected here-and-now view- point; a News Narrative Space representing the newsworthy events from a there-and-then viewpoint; and an Intermediate Space representing the informa- tion of the news actors provided from a temporal viewpoint in-between the newsworthy events and the present. Viewpoint transfers and their markers were examined in a corpus of 100 Dutch crime news narratives published over a period of fifty years. The results reveal clear patterns, which indicate that both linguistic structures and narrative-based as well as genre-based inferences play a role in the processing of news narratives. The results furthermore clarify how these narratives have been gradually crystallizing into a genre over the past decades. These findings elucidate the complex yet fluent process of conceptually moving between mental spaces, thus advancing our understanding of the rela- tion between the linguistic and the cognitive representation of narrative discourse. Keywords: viewpoint, mental spaces, news narrative, tense, temporal adverbs 1 Introduction A considerable proportion of human communication takes place in narrative formats (Bruner 1991). -

So Who Taught Master Funakoshi?

OSS!! Official publication of KARATENOMICHI MALAYSIA VOLUME 1 EDITION 1 SO WHO TAUGHT MASTER FUNAKOSHI? Tomo ni Karate no michi ayumu In his bibliography, Gichin Funakoshi wrote that he had two main teachers, Masters Azato and Itosu, though he s ometimes trained under IN THIS ISSUE Matsumura, Kiyuna, Kanryo Higaonna, and SO WHO TAUGHT MASTER Niigaki. Who were these two Masters and FUNAKOSHI? SHU-HA-RI how did they influence him? ISAKA SENSEI FUNDAMENTALS (SIT DOWN LESSON) : SEIZA Yasutsune “Ankoh” Azato (1827–1906) was born into a family of hereditary THE SHOTO CENTRE MON chiefs of Azato, a village between the towns of Shuri and Naha. Both he and his good friend Yasutsune Itosu learned karate from Sokon FUNAKOSHI O’SENSEI MEMORIAL “Bushi” Matsumura, bodyguard to three Okinawan kings. He had legendary GASSHUKU 2009 martial skills employing much intelligence and strategy over strength and 2009 PLANNER ferocity. Funakoshi states that though lightly built when he began training, after a few years Azato as well as Itosu had developed their physiques “to admirable and magnificent degrees.” ANGRY WHITE PYJAMAS FIGHT SCIENCE Azato was skilled in karate, horsemanship, archery, Jigen Ryu ken-jutsu, MEMBER’S CONTRIBUTIONS Chinese literature and politics. SPOTLIGHT Continued on page 2 READABLES DVD FIGHT GEAR TEAM KIT FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK Welcome to the inaugural issue of OSS!! To some of the members who have been with us for quite sometime knows how long this newsletter have been in planning. Please don’t forget to send me your feedback so that I can make this newsletter a better resource for all of us. -

Kata Unlimited

Volume 1, Issue 12 Kata Unlimited April 2004 Welcome to the 12th issue of Kata Unlimited. I would like to say I was happy to be writing this edito- rial, but sadly, I have some bad news to impart and I find it quite difficult to do so. Already, your heart may sink with anticipation of what may be coming. Let me allay your fears and say straight away that I will continue to produce this newsletter, but I’m afraid that there are to be some major changes. The main problem has been that the revenue generated from the subscription fees is not enough to sus- tain the kind of effort I have put in over the last 12 months. The problem is one of a lack of interest gen- erally, with numbers of subscribers being the problem. Subsequently KU will not be sent in the post after this issue. I will be continuing to produce Kata Unlimited (in a different form - see article on page In association with: 12) but any further issues will only be available to registered members and then, only via the web site. For the small minority of you who do not have the internet, please accept my humblest apologies. www.practical-martial-arts.co.uk Inside this issue: Kaze Arashi 5 Ryu An Ending & 12 a Beginning - By Steve Chriscole No Holds 15 Barred Karate - By Simon Keegan Kata Unlimited Page 2 I’m pleased to say that a number of you who read KU have So what is to become of KU? Well, it ceases taking money been very supportive and I thank you for all the kind words in payment, and becomes a hobby and not a business (and in some cases, deeds). -

Diegesis – Mimesis

Published on the living handbook of narratology (http://www.lhn.uni-hamburg.de) Diegesis – Mimesis Stephen Halliwell Created: 17. October 2012 Revised: 12. September 2013 1 Definition Diegesis (“narrative,” “narration”) and mimesis (“imitation,” “representation,” “enactment”) are a pair of Greek terms first brought together for proto- narratological purposes in a passage from Plato’s Republic (3.392c–398b). Contrary to what has become standard modern usage (section 3 below), diegesis there denotes narrative in the wider generic sense of discourse that communicates information keyed to a temporal framework (events “past, present, or future,” Republic 392d). It is subdivided at the level of discursive style or presentation (lexis ) into a tripartite typology: 1) haple diegesis, “plain” or “unmixed” diegesis, i.e. narrative in the voice of the poet (or other authorial “storyteller,” muthologos, 392d); 2) diegesis dia mimeseos, narrative “by means of mimesis,” i.e. direct speech (including drama, Republic 394b–c) in the voices of individual characters in a story; and 3) diegesis di’ amphoteron, i.e. compound narrative which combines or mixes both the previous two types, as in Homeric epic, for example. From this Platonic beginning, the terms have had a long and sometimes tangled history of usage, right up to the present day, as a pair of critical categories. 2 Explication The diegesis/mimesis complex is introduced by Socrates at Republic 392c ff. to help categorize different ways of presenting a story, especially in poetry. His aim is to sketch a basic psychology and ethics of narrative. From Republic 2.376c ff. Socrates has been concerned with the contribution of storytelling in general, poetry (the most powerful medium of verbal narrative in Greek culture) in particular, to the education of the “guardians” of the ideal city hypothesized in the dialogue. -

Order in Multiplicity: Aristotle on Text, Context, and the Rule of Law Maureen B

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 79 | Number 3 Article 2 3-1-2001 Order in Multiplicity: Aristotle on Text, Context, and the Rule of Law Maureen B. Cavanaugh Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Maureen B. Cavanaugh, Order in Multiplicity: Aristotle on Text, Context, and the Rule of Law, 79 N.C. L. Rev. 577 (2001). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol79/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORDER IN MULTIPLICITY:* ARISTOTLE ON TEXT, CONTEXT, AND THE RULE OF LAW MAUREEN B. CAVANAUGH* Justice Scalia has made the question of textual interpretation tantamount to a referendum on whether we are a government characterizedby the "rule of law" or the "rule of men." Aristotle is frequently quoted in support of statements about the rule of law and methods of statutory interpretation. While frequent, quotation of and reliance on Aristotle has been selective. The dichotomy between methods of interpretationand the rule of law turns out to be a false one. This Article examines Aristotle's theories of interpretation,especially his analysis of homonymy, non-univocal uses of the same word, to show that not all homonyms are random. Aristotle's contribution,that associatedhomonyms allow us to understand related ideas, along with his principles of language and logic, permit us to address the central question of how to interpret a text. -

SKI USF Newletter December 2005

4TH QUARTER NEWSLETTER SHOTOKAN KARATE-DO INTERNATIONAL U.S. FEDERATION DECEMBER 2005 AN INTERVIEW WITH SUZUKI RYUSHO SENSEI: A MOMENT IN TIME INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Nearly twenty years since his 22nd, 23rd, 24th and 25th All last visit to the U.S., Suzuki SKIF Japan Championships. Ryusho Sensei was greeted by Currently the Director of the AN INTERVIEW 1 Northern California instructors WITH SUZUKI Soleimani, Mallari (seminar Instructor Division at Honbu RYUSHO SENSEI host), and Withrow upon his dojo, Suzuki Sensei is responsi- arrival at San Francisco Interna- ble for nine instructors and tional Airport. Following a brief oversees several phases of the Suzuki Sensei demonstrates KERI/THEORY AND 2 training program prior to their PRACTICE check-in and rest period at the proper hip position. hotel, the welcome party ush- teaching assignments with the ered Suzuki to a delectable SKIF organization. Below: Seminar attendees KARATE: A 3 feast of sushi at one of in San Jose, California, USA PSYCHOLOGICAL A graduate of International APPROACH Berkeley, California’s finest Budo University, Suzuki began Japanese restaurants. his marital arts training at age (focus) as a “spark” that oc- TAKUSHOKU 3 six and continued under his curs when all the elements Dinner time conversation is a come together at the precise UNIVERSITY wonderful way to get re- father’s instruction for ten years until he met Kanazawa Kancho moment of impact. This can acquainted and catch up on the be illustrated as necessary news from afar. Suzuki was and applied for membership EDITIOR’S 4 with SKIF. He received the rank ingredients for combustion: a COLUMN: receptive to our questions and fuel supply, sufficient oxygen was eager to share about cur- of godan (5th degree) and com- CULTURAL BASED ments that his favorite tech- and a body in motion which rent events from the Honbu creates the spark to start a HEALING dojo in Tokyo. -

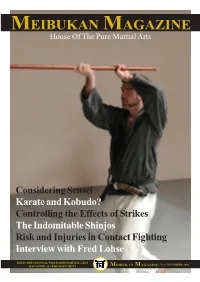

Of Okinawan Uechi-Ryu Karate

MEIBUKAN MAGAZINE House Of The Pure Martial Arts Considering Sensei Karate and Kobudo? Controlling the Effects of Strikes The Indomitable Shinjos Risk and Injuries in Contact Fighting Interview with Fred Lohse Fred Lohse with bo. Courtesy of Jim Baab. THE INTERNATIONAL WEB BASED MARTIAL ARTS No 8 DECEMBER 2006 MAGAZINE AS A PDF DOCUMENT MEIBUKAN MAGAZINE House of the Pure Martial Arts WWW.MEIBUKANMAGAZINE.ORG No 8 DECEMBER 2006 MEIBUKAN MAGAZINE House of the Pure Martial Arts No 8 DECEMBER 2006 MISSION STATEMENT Column 2 Meibukan Magazine is an initiative of founders Lex Opdam and Mark Hemels. Aim of this web based We want your help! magazine is to spread the knowledge and spirit of the martial arts. In a non profitable manner Meibukan Magazine draws attention to the historical, spiritual Feature 2 and technical background of the oriental martial arts. Starting point are the teachings of Okinawan karate- Karate and Kobudo? do. As ‘House of the Pure Martial Arts’, however, Fred Lohse takes us on a journey through the history of karate and kobudo in Meibukan Magazine offers a home to the various au- thentic martial arts traditions. an effort to explain why the two are actually inseparable. FORMAT Interview 9 Meibukan Magazine is published several times a year Interview with Fred Lohse in an electronical format with an attractive mix of subjects and styles. Each issue of at least twelve Lex Opdam interviews Goju-ryu and Matayoshi kobudo practitioner Fred pages is published as pdf-file for easy printing. Published Lohse. editions remain archived on-line. Readers of the webzine are enthousiasts and practi- tioners of the spirit of the martial arts world wide.