Negotiating Multicultural, Aboriginal and Canadian Identity Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada in the Classroom

Canada in the Classroom Notes to Accompany PowerPoint Presentation (Given at the Canadian Consulate in Denver in September 2005) by Nadine Fabbi, University of Washington Slide #1 – Canadian Studies in the U.S. This power point presentation will introduce you to Canadian Studies in the U.S. and to the rationale behind international education in the U.S. It will orient you to the Canadian Studies “community” and answer the question, “Why study Canada?” In addition, the presentation will provide a quick overview of Canadian-American history and the Linking: Connecting Canadian History to the U.S. curriculum modules available on the K-12 STUDY CANADA website. Slide #2 – Sputnik 1 In 1957, at the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite – Sputnik 1. Its launch kicked off the Space Race but, more important to this discussion, the U.S. responded by setting in place a reform movement in science and international education. Millions of dollars were immediately poured into scientific research and international education and the U.S. Department of Education’s International Programs were created. (The largest increase in funding in international programs since that time came after 9/11.) The U.S. defined international education as critical to global competitiveness and to the peaceful resolution of conflict. And, as our world shrinks in size, international studies is increasingly relevant. Slide #3 – Map with National Resource Centers One of the many federally-funded international programs are the Title VI programs whose mandate is to increase international studies content in teaching and research not only at the level of higher education, but also with the general public, business, media, the government, and for K-12 educators. -

Discover Canada the Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship 2 Your Canadian Citizenship Study Guide

STUDY GUIDE Discover Canada The Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship 2 Your Canadian Citizenship Study Guide Message to Our Readers The Oath of Citizenship Le serment de citoyenneté Welcome! It took courage to move to a new country. Your decision to apply for citizenship is Je jure (ou j’affirme solennellement) another big step. You are becoming part of a great tradition that was built by generations of pioneers I swear (or affirm) Que je serai fidèle before you. Once you have met all the legal requirements, we hope to welcome you as a new citizen with That I will be faithful Et porterai sincère allégeance all the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. And bear true allegiance à Sa Majesté la Reine Elizabeth Deux To Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second Reine du Canada Queen of Canada À ses héritiers et successeurs Her Heirs and Successors Que j’observerai fidèlement les lois du Canada And that I will faithfully observe Et que je remplirai loyalement mes obligations The laws of Canada de citoyen canadien. And fulfil my duties as a Canadian citizen. Understanding the Oath Canada has welcomed generations of newcomers Immigrants between the ages of 18 and 54 must to our shores to help us build a free, law-abiding have adequate knowledge of English or French In Canada, we profess our loyalty to a person who represents all Canadians and not to a document such and prosperous society. For 400 years, settlers in order to become Canadian citizens. You must as a constitution, a banner such as a flag, or a geopolitical entity such as a country. -

Hepatitis C Outreach, Education and Media for Ethnoracial

HEPATITIS C OUTREACH, EDUCATION AND MEDIA FOR ETHNORACIAL COMMUNITIES IN ONTARIO Hywel Tuscano, Fozia Tanveer, Ed Jackson, Jim Pollock, Jeff Rice CATIE (Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange) BACKGROUND RESULT(S) From 2011–2014 CATIE developed an Ethnocultural Hepatitis C Education and Outreach project that produced in-language hepatitis C resources and a media Education Outreach campaign for four major immigrant communities living in Ontario: Pakistani, The website yourlanguage.hepcinfo.ca has basic hepatitis C information The project has partnered with over 20 organizations. Event outreach each Punjabi, Chinese and Filipino. in 9 languages—Bengali, Hindi, English, Punjabi, Simplified Chinese, Spanish, year reaches over 2000 people. Tagalog, Urdu, Vietnamese—and receives over 1000 visits monthly. Social Marketing PURPOSE Three waves of a hepatitis C awareness campaign have run in up to 26 ethnocultural print, radio and online outlets. Editorial content was also Of all the hepatitis C infections reported in Canada, 35 per cent are estimated produced including articles, radio interviews and tv programs. to be among immigrants.1 Immigrants often report better health than the general population upon arriving in Canada but their health is reported to decline over time: The Healthy Immigrant Effect. Studies report that immigrants in Canada access the healthcare system less than people born in Canada and often face cultural and linguistic barriers to services and information.2 In-language resources and community development are required to engage these communities in health issues. METHOD FINDINGS The project maintains a facilitator roster of 16 people able to deliver The project was developed through partnership and community consultation workshops in five languages: Mandarin, Tagalog, Urdu, Punjabi and Spanish. -

20-4.4 Canadian National Identity

20-4.4 Canadian National Identity National Identity 1. Survey your classmates to find out what being Canadian means to them. Fill out the organizer below. Student’s Name What being a Canadian means to him or her: Share your answers with classmates and create a class poster that illustrates what being Canadian means to students in your class. Knowledge and Employability Studio Social Studies 20-4.4 Canadian National Identity ©Alberta Education, April 2019 (www.LearnAlberta.ca) National Identity 1/11 2. Did the people in your class express different points of view on Canadian identity? Your culture and personal experiences may affect your perspective on what it means to be Canadian. Find out how the different types of Canadians below feel about Canadian identity and fill in the diagram with key words that describe their feelings. First Nations French New Canadians Immigrants Canadian Identity Urban Descendants Dwellers of European Settlers Rural Dwellers Knowledge and Employability Studio Social Studies 20-4.4 Canadian National Identity ©Alberta Education, April 2019 (www.LearnAlberta.ca) National Identity 2/11 3. Choose one of the groups from the previous Use these tools: question or another group and conduct a more thorough investigation of how people in that Getting Started with Research group feel about Canadian identity. Create a Recording Information simple presentation of your findings. If possible, include interviews and quotes. 4. To better understand symbols that promote a collective identity in Canada, follow these steps. Step one: Explain the history and importance of the following symbols of Canadian national identity. The Canadian Coat of Arms The Canadian Flag (Maple Leaf) The Canadian National Anthem (O Canada) Step two: Identify 10 Where to Start on the Web other symbols that promote Canadian https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian- identity and what each heritage/services/official-symbols-canada.html represents. -

Human Geography of Canada: Developing a Vast Wilderness

Chapter 7 Guided Notes _________________________________________________________________________________________ NAME Human Geography of Canada: Developing a Vast Wilderness Three major groups in Canada—the native peoples, the French, and the English—have melded into a diverse and economically strong nation. Section 1: History and Government of Canada French and British settlement greatly influenced Canada’s political development. Canada’s size and climate affected economic growth and population distribution. The First Settlers and Colonial Rivalry Early Peoples After Ice Age, migrants cross Arctic land bridge from Asia o ancestors of Arctic Inuit (Eskimos); North American Indians to south Vikings found Vinland (Newfoundland) about A.D. 1000; later abandon Colonization by France and Britain French explorers claim much of Canada in 1500–1600s as “New France”; British settlers colonize the Atlantic Coast Steps Toward Unity Establishing the Dominion of Canada In 1791 Britain creates two political units called provinces o Upper Canada (later, Ontario): English-speaking, Protestant; Lower Canada (Quebec): French-speaking, Roman Catholic Rupert’s Land a northern area owned by fur-trading company Immigrants arrive, cities develop: Quebec City, Montreal, Toronto o railways, canals are built as explorers seek better fur-trading areas Continental Expansion and Development From the Atlantic to the Pacific In 1885 a transcontinental railroad goes from Montreal to Vancouver o European immigrants arrive and Yukon gold brings fortune hunters; -

Asian Minorities in Canada: Focusing on Chinese and Japanese People

Asian Minorities in Canada: Focusing on Chinese and Japanese People Jeong Mi Lee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto O Copyright by Jeong Mi Lee 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OnawaON K1AW OnawaON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing tk exclusive permettant a la National Lïbrary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Asian Minorities in Canada: Focusing on Chinese and Japanese People Master of Arts, 1999 Jeong Mi Lee Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto Abstract Canada consists of immigrants from al1 over the world - and it creates diverse cultures in one society. Arnong them, Asian immigrants from China and Japan have especially experienced many difficulties in the early period. -

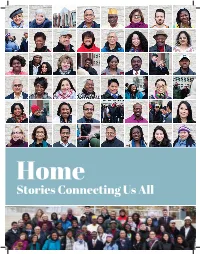

Stories Connecting Us All

Home Stories Connecting Us All Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 1 Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 2 Home Stories Connecting Us All Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 3 Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 4 Home Stories Connecting Us All Edited by Tololwa M. Mollel Assisted by Scott Sabo Book design and cover photography by Stephanie Simpson Edmonton, Alberta Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 5 © 2017 Authors All rights reserved. No work in this book can be reproduced without written permission from the respective author. ISBN: in process Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 6 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................13 ASSIST Community Services Centre: Bridging People & Communities ...............45 Letter from the Prime Minister ..................17 by the Board and Staff of ASSIST Community Services Centre War and Peace ...................................................19 To the Far North .............................................. 48 by Hussein Abdulahi by Nathaniel Bimba The International and Heritage Embracing Our Differences ..........................51 Languages Association’s Contributions to by Mila Bongco-Philipzig Multiculturalism and Multilingualism- 40 Years of Service .................................................22 Lado Luala ...........................................................54 by Trudie Aberdeen, PhD by Barizomdu Elect Lebe Boogbaa Finding a Job in Alberta .................................25 My Amazing Race ............................................ 56 by A.E.M. -

Citizenship Revocation in the Mainstream Press: a Case of Re-Ethni- Cization?

CITIZENSHIP REVOCATION IN THE MAINSTREAM PRESS: A CASE OF RE-ETHNI- CIZATION? ELKE WINTER IVANA PREVISIC Abstract. Under the original version of the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (2014), dual citizens having committed high treason, terrorism or espionage could lose their Canadian citizenship. In this paper, we examine how the measure was dis- cussed in Canada’s mainstream newspapers. We ask: who/what is seen as the target of citizenship revocation? What does this tell us about the direction that Canadian citizenship is moving towards? Our findings show that Canadian newspapers were more often critical than supportive of the citizenship revocation provision. However, the press ignored the involvement of non-Muslim, white, Western-origin Canadians in terrorist acts and interpreted the measure as one that was mostly affecting Canadian Muslims. Thus, despite advocating for equal citizenship in principle, in their writing and reporting practice, Canadian newspapers constructed Canadian Muslims as sus- picious and less Canadian nonetheless. Keywords: Muslim Canadians; Citizenship; Terrorism; Canada; Revocation Résumé: Au sein de la version originale de la Loi renforçant la citoyenneté cana- dienne (2014), les citoyens canadiens ayant une double citoyenneté et ayant été condamnés pour haute trahison, pour terrorisme ou pour espionnage, auraient pu se faire révoquer leur citoyenneté canadienne. Dans cet article, nous étudions comment ce projet de loi fut discuté au sein de la presse canadienne. Nous cherchons à répondre à deux questions: Qui/quoi est perçu comme pouvant faire l’objet d’une révocation de citoyenneté? En quoi cela nous informe-t-il sur les orientations futures de la citoy- enneté canadienne? Nos résultats démontrent que les journaux canadiens sont plus critiques à l’égard de la révocation de la citoyenneté que positionnés en sa faveur. -

Language Education, Canadian Civic Identity and the Identities of Canadians

LANGUAGE EDUCATION, CANADIAN CIVIC IDENTITY AND THE IDENTITIES OF CANADIANS Guide for the development of language education policies in Europe: from linguistic diversity to plurilingual education Reference study Stacy CHURCHILL Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto Language Policy Division DG IV – Directorate of School, Out-of-School and Higher Education Council of Europe, Strasbourg French edition: L’enseignement des langues et l’identité civique canadienne face à la pluralité des identités des Canadiens The opinions expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All correspondence concerning this publication or the reproduction or translation of all or part of the document should be addressed to the Director of School, Out- of-School and Higher Education of the Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex). The reproduction of extracts is authorised, except for commercial purposes, on condition that the source is quoted. © Council of Europe, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .........................................................................................................................5 1. Introduction.........................................................................................................7 2. Linguistic And Cultural Identities In Canada ......................................................8 3. Creating Identity Through Official Bilingualism...............................................11 3.1. Origins of Federal -

'O Canada' and the Two Solitudes

‘O Canada’ and the Two Solitudes James Bowden e should speak not of one “O Canada” but Des plus brillants exploits. Wof the two O Canadas, which represent Et ta valeur, de foi trempée, the two solitudes of English and French Canada. Protégera nos foyers et nos droits. The original French lyrics of Sir Adolphe-Basile Protégera nos foyers et nos droits. Routhier and the English lyrics of Sir Robert Stanley Weir bear no resemblance to each oth- Translation: er. The French lyrics celebrate the French Fact and commemorate a glorious crusade to Chris- O Canada, tianize North America with lines like “he knows land of our ancestors to carry the sword; he knows to carry the cross” Glorious deeds circle your brow and “valour steeped in faith”; in contrast, the For your arm knows how to wield the sword English lyrics appeal to a Loyalist patriotism, Your arm knows how to carry the cross; where the “true” in “True North” suggests the Your history is an epic virtues of steadfastness and loyalty. of brilliant deeds Parliament adopted Routhier’s original And your valour steeped in faith French text of “O Canada” and a modified ver- will protect our homes and our rights, sion of Weir’s English version of “O Canada” as Will protect our homes and our rights. the official national anthem through the Na- tional Anthem Act of 1980. The English lyrics Weir’s original poem from 1908 said: derived from the modifications that a Special Joint Committee of the House of Commons and O Canada! Senate had recommended to Weir’s poem in Our home, our native land. -

After the Financial Crisis, What Should a Model Central Bank Look Like?

Central Bank Independence Revisited: After the financial crisis, what should a model central bank look like? Ed Balls, James Howat, Anna Stansbury April 2018 M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series | No. 87 The views expressed in the M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series have not undergone formal review and approval; they are presented to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government Weil Hall | Harvard Kennedy School | www.hks.harvard.edu/mrcbg MR- CBG WORKING PAPER April 2018 Central Bank Independence Revisited: After the financial crisis, what should a model central bank look like? Ed Balls Research Fellow, Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, John F Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University & Visiting Professor, King’s College London James Howat John F Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University Anna Stansbury John F Kennedy School of Government & Economics Department, Harvard University An earlier version of this paper was published in September 2016 as a working paper by the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at Harvard University. It was largely written during Ed’s term as Senior Fellow at the M-RCBG, during which James was an MPP student and before Anna began her PhD course. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at a Harvard-wide panel event on 27th March 2017, at the Feldstein-Friedman Macroeconomic Policy Seminar in the Department of Economics, Harvard University on 1st March 2016 and to the Senior Fellows Meeting at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, Harvard Kennedy School in February 2016. -

KHAN-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf

O CANADA, WHOSE HOME AND NATIVE LAND? AN AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE INQUIRY INTO THE CRITICAL ROLE OF CURRICULUM IN IDENTITY AFFIRMATION A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of Curriculum Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon Canada By MOMINA A. KHAN Copyright Momina A. Khan, July, 2018. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Curriculum Studies University of Saskatchewan 28 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 0X1 Canada Dean of College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Saskatchewan 116 Thorvaldson Building, 110 Science Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5C9 Canada i Abstract The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) guarantees fundamental freedoms of conscience, religion, thought, belief, and opinion.