Higher Education in Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vietnam's Extraordinary Performance in the PISA Assessment

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 13066 Vietnam’s Extraordinary Performance in the PISA Assessment: A Cultural Explanation of an Education Paradox M Niaz Asadullah Liyanage Devangi Perera Saizi Xiao MARCH 2020 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 13066 Vietnam’s Extraordinary Performance in the PISA Assessment: A Cultural Explanation of an Education Paradox M Niaz Asadullah University of Malaya, University of Reading, SKOPE and IZA Liyanage Devangi Perera Monash University Saizi Xiao University of Malaya MARCH 2020 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. -

Ethnic Disparities in Education in Vietnam

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The Department of Human Development and Family Studies ETHNIC DISPARITIES IN EDUCATION IN VIETNAM A Dissertation in Human Development and Family Studies and Demography by Quang Thanh Trieu @2018 Quang Thanh Trieu Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2018 The dissertation of Quang T. Trieu was reviewed and approved* by the following: Rukmalie Jayakody Associate Professor of Human Development and Family Studies and Sociology Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Scott D. Gest Professor of Human Development and Family Studies Professor-in-Charge of the Human Development and Family Studies Undergraduate Program Leif Jensen Distinguished Professor of Rural Sociology and Demography David M. Post Professor of Education (Educational Theory & Policy and Comparative & International Education) and Senior Scientist Lisa Gatzke-Kopp, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Human Development and Family Studies Professor in Charge- Graduate Program *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract Education plays an important role in determining individuals’ socioeconomic attainment and a nation’s competitiveness on the global stage. Thus, educational disparities not only prevent vulnerable populations from gaining access to a better life but also hinder a nation’s development. Theoretically, economic growth provides more resources for education. However, initial observations in many developing countries show that economic growth does not bring the same educational benefits to everyone. Vietnam offers an interesting context in which to study ethnic educational disparities in a developing country transforming from a centrally planned to a market-driven economy. After socioeconomic transformations, Vietnam has achieved significant progress, including economic and educational growth. -

Issues in the Implementation of Bilingual Education in Vietnam

TESOL Working Paper Series Issues in the Implementation of Bilingual Education in Vietnam Do-Na Chi* An Giang University, Vietnam Abstract This paper explores the implementation of bilingual education at a private institution in Vietnam, with a focus on its successes and challenges. Despite long-term English education as a compulsory subject at grade levels 3 to 12, there is still a need for Vietnamese learners of English to improve their language profciency beyond the national curriculum. For that reason, many institutions have been established to make English a more important part of the curriculum, not simply a subject but a means of communication and a medium of instruction. In other words, the aim is to make those learners reach bilingualism. However, training learners to be bilingual is not an easy mission, since it has numerous requirements. Observing how bilingual education was implemented at a private institution in Vietnam, this paper reveals some positive effects on learners’ language development along with challenges regarding teaching materials, qualifed staff, and negative infuences of the national curriculum. Introduction While English is a mandatory subject in Vietnam, the focus is still on grammar and vocabulary, not communicative competence (Denham, 1992; Nunan, 2003). To develop English language profciency of future generations of Vietnamese students, the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) proposed the use of English as the medium of instruction at high school and college levels nationwide (MOET, 2008). As stated by MOET in Directive 1400, the national curriculum embarked on a project entitled “Teaching and Learning in English in the National Education System 2008-2020,” or “Project 2020” for short. -

Moral Education in a Non-Traditional Setting in Vietnam

BENDING BAMBOO: MORAL EDUCATION IN A NON-TRADITIONAL SETTING IN VIETNAM Eric J. Buetikofer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Patricia Kubow, Advisor Christopher Frey William Wiseman ii © 2009 Eric Buetikofer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Patricia Kubow, Advisor Vietnam is a country rich with culture and tradition. This thesis examines the cultural practice of teaching morality in a non-traditional school in Vietnam. This qualitative case study took place in a non-traditional school located in central Vietnam that caters to street children. Findings from the participant interviews are discussed through the use of vignettes. The vignette themes include morality, citizenship, philosophical association, gender and one’s ability to be moral, bending bamboo and morality, morality and role playing, street children and moral education, learning and importance of language, learning English as a Second Language in the school, and debates and learning good citizenship. Each vignette is discussed using information from participant interviews and Western and Eastern moral education practices. Research for this paper has been completed utilizing educational and psychological theoretical literature concerning moral education and moral philosophy in conjunction with empirical studies conducted in Vietnam. iv This thesis is dedicated to my wife Jessica Turos and my mother Kathy Buetikofer, who have been supportive in all of my educational endeavors. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my Thesis committee, Dr. Kubow, Dr. Frey, and Dr. Wiseman, for all of their guidance. I could not have completed this formidable project without you. -

Air America in South Vietnam I – from the Days of CAT to 1969

Air America in South Vietnam I From the days of CAT to 1969 by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 11 August 2008, last updated on 24 August 2015 I) At the times of CAT Since early 1951, a CAT C-47, mostly flown by James B. McGovern, was permanently based at Saigon1 to transport supplies within Vietnam for the US Special Technical and Economic Mission, and during the early fifties, American military and economic assistance to Indochina even increased. “In the fall of 1951, CAT did obtain a contract to fly in support of the Economic Aid Mission in FIC [= French Indochina]. McGovern was assigned to this duty from September 1951 to April 1953. He flew a C-47 (B-813 in the beginning) throughout FIC: Saigon, Hanoi, Phnom Penh, Vientiane, Nhatrang, Haiphong, etc., averaging about 75 hours a month. This was almost entirely overt flying.”2 CAT’s next operations in Vietnam were Squaw I and Squaw II, the missions flown out of Hanoi in support of the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu in 1953/4, using USAF C-119s painted in the colors of the French Air Force; but they are described in the file “Working in Remote Countries: CAT in New Zealand, Thailand-Burma, French Indochina, Guatemala, and Indonesia”. Between mid-May and mid-August 54, the CAT C-119s continued dropping supplies to isolated French outposts and landed loads throughout Vietnam. When the Communists incited riots throughout the country, CAT flew ammunition and other supplies from Hanoi to Saigon, and brought in tear gas from Okinawa in August.3 Between 12 and 14 June 54, CAT captain -

Linguistic Minority Learners in Mainstream Education in Vietnam: an Ethnographic Case Study of Muong Pupils in Their Early Years

Linguistic minority learners in mainstream education in Vietnam: an ethnographic case study of Muong pupils in their early years Chung Pham Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) The University of Leeds School of Education September 2016 - ii - I confirm that the work submitted is my own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Chung Pham to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © <2016> The University of Leeds and <Chung Pham> - iii - Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank my first supervisor, Dr Jean Conteh, and my second supervisor, Dr Mary Chambers, for their extensive and invaluable guidance and endless encouragement in helping me progress through this study as smoothly as possible. The tireless academic support they have provided me throughout my time in Leeds has been amazing and their patience and empathy when tolerating my lagging behind the timeline due to personal issues has been no less remarkable. Their knowledge of when to give me a bit of a push and when to offer some space on this challenging journey has been tremendously appreciated and has been a great source of motivation for the completion of the study. Secondly I would like to thank the participants: the head teacher, the Deputy Head, all the teachers, the children and their families, for allowing me to carry out my research in the way that I did. -

The Current Situation and Issues of the Teaching of English in Vietnam

The Current Situation and Issues of the Teaching of English in Vietnam HOANG Van Van Introduction This paper is concerned with the current situation and issues of the teaching of English in Vietnam. As a way of start, I will first provide a brief history of English language teaching in Vietnam. Then I will examine in some depth the current situation of English language teaching in Vietnam, looking specifically at English language teaching both inside and outside the formal educational system. The final section is devoted to a discussion of some of the problems we have been experiencing in the teaching of English in Vietnam in the context of integration and globalization. 1. A Brief History of English Language Teaching in Vietnam The history of English language teaching in Vietnam can be roughly divided into two periods: (i) English in Vietnam before 1986 and (ii) English in Vietnam from 1986 up to the present. The reason for this way of division is that 1986 was the year when the Vietnamese Communist Party initiated its overall economic reform, exercising the open-door policy, and thus marking the emergence of English as the number 1 foreign language in Vietnam. 1.1 English in Vietnam before 1986 English in Vietnam before 1986 had a chequered history. Chronologically, the teaching of English in Vietnam can be subdivided into three periods: the first period extends from the beginning of the French invasion of Vietnam up to 1954; the second period, from 1954 to 1975; and the third period, from 1975 to 1986. Each of the periods will be examined in some depth in the sections that follow. -

Overview of Vietnam's Legal Framework for Foreign Education Providers

OVERVIEW OF THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK AFFECTING THE PROVISION OF FOREIGN EDUCATION IN VIETNAM This overview provides information on laws and associated regulations relevant to the provision of foreign education in Vietnam. Disclaimer This overview provides general information on the laws that affect the provision of foreign education in Vietnam. Care should be taken when interpreting Vietnam’s legal framework, as: - it is undergoing continual revision and reform; - the structure and expression of Vietnamese legal instruments can be quite general or extremely precise; - English translations of Vietnamese legal instruments are often contested and seldom definitive; and - local interpretation and enforcement of the legal framework can vary. The Australian Government assumes no responsibility for any reliance on information contained in this overview. In addition to doing their own market research and due diligence, foreign education providers seeking to operate in Vietnam should seek independent professional legal and other advice. I Vietnam’s legal framework 1 The legal framework of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam is significantly different to that of Australia. While the National Assembly is the highest authority under the Constitution, Government Ministries are responsible for drafting and implementing legislation. These Ministries can effect changes in the legal framework quickly and with little notice. Consequently, the views of relevant Ministries hold significant weight in the Vietnamese legal framework. The main types of legal instrument -

The EC-Vietnam Country Strategy Paper 2002-2006 & National

(&9,(71$0 &28175<675$7(*<3$3(5 ± WKH(&9LHWQDP1$7,21$/,1',&$7,9(352*5$00(LVDWWDFKHG 7$%/(2)&217(176 9,(71$0$7$*/$1&(«««««««««««««««, /,672)$%%5(9,$7,216«««««««««««««««,, 6800$5< (8523($1&20081,7<&223(5$7,212%-(&7,9(6 7+(32/,&<$*(1'$2)9,(71$0 &28175<$1$/<6,6 3ROLWLFDOVLWXDWLRQ (FRQRPLFDQGVRFLDOVLWXDWLRQ 6WUXFWXUHDQGSHUIRUPDQFH 6RFLDO'HYHORSPHQWV 7KHUHIRUPSURFHVV 3XEOLFILQDQFHDQGVHFWRUDOSROLFLHV ([WHUQDOHQYLURQPHQW 6XVWDLQDELOLW\RIFXUUHQWSROLFLHV 0HGLXP7HUP&KDOOHQJHV 29(59,(:2)3$67$1'21*2,1*(&&223(5$7,21 2YHUYLHZ 3DVWDQG2QJRLQJ(&&RRSHUDWLRQ/HVVRQVOHDUQHG (80HPEHU6WDWHV¶DQGRWKHUGRQRUV¶SURJUDPPHV 7+((&5(63216(675$7(*< 0DLQDUHDVRIFRQFHQWUDWLRQ )RFDOSRLQW,PSURYHPHQWRIKXPDQGHYHORSPHQW )RFDOSRLQW,QWHJUDWLRQLQWRWKHLQWHUQDWLRQDOHFRQRP\ &URVVFXWWLQJWKHPHV &RKHUHQFHDQGFRPSOHPHQWDULW\ 9LHWQDP0DS $11(;'(9(/230(17,1',&$7256 $11(;$1,//8675$7,212)7+(85%$1585$/63/,7 $11(;21*2,1*(&&223(5$7,21352-(&76 $11(;(8'HYHORSPHQW&RRSHUDWLRQZLWK9LHWQDPE\0HPEHU6WDWH $11(;&RXQWU\(QYLURQPHQWDO%ULHI 2 9,(71$0$7$*/$1&( 3RSXODWLRQ 78.5 million (2000) DQQXDOSRSXODWLRQJURZWK 1.3% (2000) 3UHVLGHQW: Mr. Tran Duc Luong 3ULPH0LQLVWHU: Mr. Phan Van Khai &396HFUHWDU\*HQHUDO: Mr. Nong Duc Manh. 1H[WQDWLRQDOHOHFWLRQ: April 2002 6HOHFWHGHFRQRPLFLQGLFDWRUV GDP per capita: 419 ¼ GDP growth rate: 5.5% (2000) Rate of inflation: minus 1.7% (2000) Gross reserves: 3.2 billion ¼HTXLYDOHQWWRPRQWKVRILPSRUWV 6HOHFWHGVRFLDOLQGLFDWRUV Life expectancy at birth: 69 years (1999) Infant mortality rate: 36.7 per thousand births (1999) Child malnutrition: -

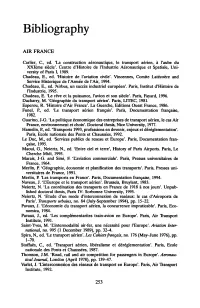

Bibliography

Bibliography AIR FRANCE Carlier, c., ed. 'La construction aeronautique, Ie transport aenen, a I'aube du XXIeme siecle'. Centre d'Histoire de l'Industrie Aeronautique et Spatiale, Uni versity of Paris I, 1989. Chadeau, E., ed. 'Histoire de I'aviation civile'. Vincennes, Comite Latecoere and Service Historique de l'Annee de l'Air, 1994. Chadeau, E., ed. 'Airbus, un succes industriel europeen'. Paris, Institut d'Histoire de l'Industrie, 1995. Chadeau, E. 'Le reve et la puissance, I'avion et son siecle'. Paris, Fayard, 1996. Dacharry, M. 'Geographie du transport aerien'. Paris, LITEC, 1981. Esperou, R. 'Histoire d'Air France'. La Guerche, Editions Ouest France, 1986. Funel, P., ed. 'Le transport aerien fran~ais'. Paris, Documentation fran~aise, 1982. Guarino, J-G. 'La politique economique des entreprises de transport aerien, Ie cas Air France, environnement et choix'. Doctoral thesis, Nice University, 1977. Hamelin, P., ed. 'Transports 1993, professions en devenir, enjeux et dereglementation'. Paris, Ecole nationale des Ponts et Chaussees, 1992. Le Due, M., ed. 'Services publics de reseau et Europe'. Paris, Documentation fran ~ise, 1995. Maoui, G., Neiertz, N., ed. 'Entre ciel et terre', History of Paris Airports. Paris, Le Cherche Midi, 1995. Marais, J-G. and Simi, R 'Caviation commerciale'. Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 1964. Merlin, P. 'Geographie, economie et planification des transports'. Paris, Presses uni- versitaires de France, 1991. Merlin, P. 'Les transports en France'. Paris, Documentation fran~aise, 1994. Naveau, J. 'CEurope et Ie transport aerien'. Brussels, Bruylant, 1983. Neiertz, N. 'La coordination des transports en France de 1918 a nos jours'. Unpub lished doctoral thesis, Paris IV- Sorbonne University, 1995. -

Air America in South Vietnam III the Collapse by Dr

Air America in South Vietnam III The Collapse by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 11 August 2008, last updated on 24 August 2015 Bell 205 N47004 picking up evacuees on top of the Pittman Building on 29 April 1975 (with kind permission from Philippe Buffon, the photographer, whose website located at http://philippe.buffon.free.fr/images/vietnamexpo/heloco/index.htm has a total of 17 photos depicting the same historic moment) 1) The last weeks: the evacuation of South Vietnamese cities While the second part of the file Air America in South Vietnam ended with a China Airlines C-123K shot down by the Communists in January 75, this third part begins with a photo that shows a very famous scene – an Air America helicopter evacuating people from the rooftop of the Pittman Building at Saigon on 29 April 75 –, taken however from a different angle by French photographer Philippe Buffon. Both moments illustrate the situation that characterized South Vietnam in 1975. As nobody wanted to see the warnings given by all 1 those aircraft downed and shot at,1 the only way left at the end was evacuation. For with so many aircraft of Air America, China Airlines and even ICCS Air Services shot down by Communists after the Cease-fire-agreement of January 1973, with so much fighting in the South that occurred in 1973 and 1974 in spite of the Cease-fire-agreement, nobody should have been surprised when North Vietnam overran the South in March and April 75. Indeed, people who knew the situation in South Vietnam like Major General John E. -

Contributions to the Political Economy of Learning Jonathan D

RISE Working Paper 21/062 February 2021 Outlier Vietnam and the Problem of Embeddedness: Contributions to the Political Economy of Learning Jonathan D. London Abstract Recent literature on the political economy of education highlights the role of political settlements, political commitments, and features of public governance in shaping education systems’ development and performance around learning. Vietnam’s experiences provide fertile ground for the critique and further development of this literature including, especially, its efforts to understand how features of accountability relations shape education systems’ performance across time and place. Globally, Vietnam is a contemporary outlier in education, having achieved rapid gains in enrolment and strong learning outcomes at relatively low levels of income. This paper proposes that beyond such felicitous conditions as economic growth and social historical and cultural elements that valorize education, Vietnam’s distinctive combination of Leninist political commitments to education and high levels of societal engagement in the education system often works to enhance accountability within the system in ways that contribute to the system’s coherence around learning; reflecting the sense and reality that Vietnam is a country in which education is a first national priority. Importantly, these alleged elements exist alongside other features that significantly undermine the system’s coherence and performance around learning. These include, among others, the system’s incoherent patterns of