Practical Considerations in the Management of Proton-Pump

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

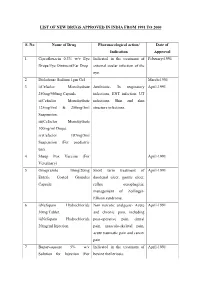

List of New Drugs Approved in India from 1991 to 2000

LIST OF NEW DRUGS APPROVED IN INDIA FROM 1991 TO 2000 S. No Name of Drug Pharmacological action/ Date of Indication Approval 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.3% w/v Eye Indicated in the treatment of February-1991 Drops/Eye Ointment/Ear Drop external ocular infection of the eye. 2 Diclofenac Sodium 1gm Gel March-1991 3 i)Cefaclor Monohydrate Antibiotic- In respiratory April-1991 250mg/500mg Capsule. infections, ENT infection, UT ii)Cefaclor Monohydrate infections, Skin and skin 125mg/5ml & 250mg/5ml structure infections. Suspension. iii)Cefaclor Monohydrate 100mg/ml Drops. iv)Cefaclor 187mg/5ml Suspension (For paediatric use). 4 Sheep Pox Vaccine (For April-1991 Veterinary) 5 Omeprazole 10mg/20mg Short term treatment of April-1991 Enteric Coated Granules duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Capsule reflux oesophagitis, management of Zollinger- Ellison syndrome. 6 i)Nefopam Hydrochloride Non narcotic analgesic- Acute April-1991 30mg Tablet. and chronic pain, including ii)Nefopam Hydrochloride post-operative pain, dental 20mg/ml Injection. pain, musculo-skeletal pain, acute traumatic pain and cancer pain. 7 Buparvaquone 5% w/v Indicated in the treatment of April-1991 Solution for Injection (For bovine theileriosis. Veterinary) 8 i)Kitotifen Fumerate 1mg Anti asthmatic drug- Indicated May-1991 Tablet in prophylactic treatment of ii)Kitotifen Fumerate Syrup bronchial asthma, symptomatic iii)Ketotifen Fumerate Nasal improvement of allergic Drops conditions including rhinitis and conjunctivitis. 9 i)Pefloxacin Mesylate Antibacterial- In the treatment May-1991 Dihydrate 400mg Film Coated of severe infection in adults Tablet caused by sensitive ii)Pefloxacin Mesylate microorganism (gram -ve Dihydrate 400mg/5ml Injection pathogens and staphylococci). iii)Pefloxacin Mesylate Dihydrate 400mg I.V Bottles of 100ml/200ml 10 Ofloxacin 100mg/50ml & Indicated in RTI, UTI, May-1991 200mg/100ml vial Infusion gynaecological infection, skin/soft lesion infection. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 De Juan Et Al

US 200601 10428A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 de Juan et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) METHODS AND DEVICES FOR THE Publication Classification TREATMENT OF OCULAR CONDITIONS (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Eugene de Juan, LaCanada, CA (US); A6F 2/00 (2006.01) Signe E. Varner, Los Angeles, CA (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/427 (US); Laurie R. Lawin, New Brighton, MN (US) (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: Featured is a method for instilling one or more bioactive SCOTT PRIBNOW agents into ocular tissue within an eye of a patient for the Kagan Binder, PLLC treatment of an ocular condition, the method comprising Suite 200 concurrently using at least two of the following bioactive 221 Main Street North agent delivery methods (A)-(C): Stillwater, MN 55082 (US) (A) implanting a Sustained release delivery device com (21) Appl. No.: 11/175,850 prising one or more bioactive agents in a posterior region of the eye so that it delivers the one or more (22) Filed: Jul. 5, 2005 bioactive agents into the vitreous humor of the eye; (B) instilling (e.g., injecting or implanting) one or more Related U.S. Application Data bioactive agents Subretinally; and (60) Provisional application No. 60/585,236, filed on Jul. (C) instilling (e.g., injecting or delivering by ocular ion 2, 2004. Provisional application No. 60/669,701, filed tophoresis) one or more bioactive agents into the Vit on Apr. 8, 2005. reous humor of the eye. Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 1 of 22 US 2006/0110428A1 R 2 2 C.6 Fig. -

Ijcep0048253.Pdf

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2017;10(4):4089-4098 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0048253 Original Article Comparative effectiveness of different recommended doses of omeprazole and lansoprazole for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis of published data Feng Liu1, Jing Wang1, Hailong Wu1, Hui Wang2, Jianxiang Wang1, Rui Zhou1, Zhi Zhu3 Departments of 1Surgery, 2Gastroenterology, 3Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Puai Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China Received January 6, 2017; Accepted February 20, 2017; Epub April 1, 2017; Published April 15, 2017 Abstract: This meta-analysis aims to evaluate the effectiveness of different recommended doses of omeprazole and lansoprazole on gastroesophageal reflux diseases (GERD) in adults. The electronic databases of PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched before September 13 2016. Fifteen eligible studies were identified involving 8752 patients in our meta-analysis. For the healing outcome of esophagitis, compared with 15 mg per day of lansoprazole, there were significant difference of both 30 mg per day of lansoprazole (RR=1.29, 95% CI [1.01, 1.66], I2=79.3%, P=0.028) and 60 mg per day of lansoprazole (RR=1.59, 95% CI [1.28, 1.99], I2=Not ap- plicable (NA), P=NA), and the other result were not significantly different between 60 mg per day and 30 mg per day. For relief of symptoms, our result indicated a significant difference between 20 mg per day and 10 mg per day of omeprazole (RR=1.21, 95% CI [1.06, 1.39], I2=53.9%, P=0.089); the overall result indicated a significant difference between lansoprazole and omeprazole (RR=0.93, 95% CI [0.86, 0.999], I2=60.7%, P=0.038). -

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPI) Preferred Step Therapy Program Annual Review Date: 01/18/2021

Policy: Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPI) Preferred Step Therapy Program Annual Review Date: 01/18/2021 Impacted Last Revised Date: Drugs: • Aciphex, Aciphex Sprinkle • Dexilant 06/17/2021 • Esomeprazole DR, esomeprazole strontium DR • Nexium • Omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate • Prevacid, Prevacid 24HR, Prevacid SoluTab • Prilosec • Protonix • Rabeprazole DR OVERVIEW Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) [i.e., esomeprazole, dexlansoprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole] are commonly used antisecretory agents that are highly effective at suppressing gastric acid and subsequently treating associated conditions, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Omeprazole is available generically and over-the-counter (OTC). Omeprazole OTC is prescription strength (20 mg). Lansoprazole is also available generically and OTC. Lansoprazole OTC is available as 15 mg capsules. Zegerid capsules are available generically and OTC; the OTC product contains omeprazole 20 mg and sodium bicarbonate 1100 mg. Nexium® 24HR (esomeprazole magnesium 22.3 mg delayed-release capsules) is available OTC and is equivalent to 20 mg of esomeprazole base. The OTC products are indicated for the short-term (14 days) treatment of heartburn. Patients should not take the OTC products for more than 14 days or more often than every 4 months unless under the supervision of a physician. Although the PPIs vary in their specific Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indications, all of the PPIs have demonstrated the ability to control GERD symptoms and to heal esophagitis when used at prescription doses. Most comparative studies between PPIs to date have demonstrated comparable efficacies for acid-related diseases, including duodenal and gastric ulcerations, GERD, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, and H. pylori eradication therapies. Though the available clinical data are not entirely complete for the comparison of these agents, many clinical trials have shown the PPIs to be similar in safety and efficacy. -

Receptor Antagonist (H RA) Shortages | May 25, 2020 2 2 2 GERD4,5 • Take This Opportunity to Determine If Continued Treatment Is Necessary

H2-receptor antagonist (H2RA) Shortages Background . 2 H2RA Alternatives . 2 Therapeutic Alternatives . 2 Adults . 2 GERD . 3 PUD . 3 Pediatrics . 3 GERD . 3 PUD . 4 Tables Table 1: Health Canada–Approved Indications of H2RAs . 2 Table 2: Oral Adult Doses of H2RAs and PPIs for GERD . 4 Table 3: Oral Adult Doses of H2RAs and PPIs for PUD . 5 Table 4: Oral Pediatric Doses of H2RAs and PPIs for GERD . 6 Table 5: Oral Pediatric Doses of H2RAs and PPIs for PUD . 7 References . 8 H2-receptor antagonist (H2RA) Shortages | May 25, 2020 1 H2-receptor antagonist (H2RA) Shortages BACKGROUND Health Canada recalls1 and manufacturer supply disruptions may be causing shortages of commonly used acid-reducing medications called histamine H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) . H2RAs include cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine and ranitidine . 2 There are several Health Canada–approved indications of H2RAs (see Table 1); this document addresses the most common: gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and peptic ulcer disease (PUD) . 2 TABLE 1: HEALTH CANADA–APPROVED INDICATIONS OF H2RAs H -Receptor Antagonists (H RAs) Health Canada–Approved Indications 2 2 Cimetidine Famotidine Nizatidine Ranitidine Duodenal ulcer, treatment ü ü ü ü Duodenal ulcer, prophylaxis — ü ü ü Benign gastric ulcer, treatment ü ü ü ü Gastric ulcer, prophylaxis — — — ü GERD, treatment ü ü ü ü GERD, maintenance of remission — ü — — Gastric hypersecretion,* treatment ü ü — ü Self-medication of acid indigestion, treatment and prophylaxis — ü† — ü† Acid aspiration syndrome, prophylaxis — — — ü Hemorrhage from stress ulceration or recurrent bleeding, — — — ü prophylaxis ü = Health Canada–approved indication; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease *For example, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome . -

Proton Pump Inhibitors

MEDICATION POLICY: Proton Pump Inhibitors Generic Name: Proton Pump Inhibitors Preferred: Esomeprazole (generic), Lansoprazole (generic), Omeprazole (generic), Therapeutic Class or Brand Name: Proton Pantoprazole (generic), and Rabeprazole Pump Inhibitors (generic) Applicable Drugs (if Therapeutic Class): Non-preferred: Aciphex® (rabeprazole), Esomeprazole (generic), Lansoprazole Dexilant® (dexlansoprazole), Nexium® (generic), Omeprazole (generic), Pantoprazole (esomeprazole), Not Medically Necessary: (generic), and Rabeprazole (generic). Omeprazole/Sodium Bicarbonate (generic), Aciphex® (rabeprazole), Dexilant® Zegerid® (omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate). (dexlansoprazole), Nexium® (esomeprazole), Prevacid® (lansoprazole), Prilosec® Date of Origin: 2/1/2013 (omeprazole), and Protonix® (pantoprazole). Date Last Reviewed / Revised: 12/23/2020 Omeprazole/Sodium Bicarbonate (generic), Zegerid® (omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate). Policy also applies to any other Proton Pump Inhibitors not listed. GPI Code: 4927002000, 4927002510, 4927004000, 4927006000, 4927007010, 4927007610, 4999600260 PRIOR AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA (May be considered medically necessary when criteria I and II are met) I. Documented diagnosis of one of the following A through G: A. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). B. Erosive esophagitis. C. Gastric ulcers. D. Risk reduction of NSAID-associated gastric ulcer. E. Duodenal ulcers. F. Eradication of H. pylori. G. Hypersecretory conditions II. Non-preferred PPIs require documented trials and failures of all generic PPIs. EXCLUSION -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,264,917 B1 Klaveness Et Al

USOO6264,917B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,264,917 B1 Klaveness et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 24, 2001 (54) TARGETED ULTRASOUND CONTRAST 5,733,572 3/1998 Unger et al.. AGENTS 5,780,010 7/1998 Lanza et al. 5,846,517 12/1998 Unger .................................. 424/9.52 (75) Inventors: Jo Klaveness; Pál Rongved; Dagfinn 5,849,727 12/1998 Porter et al. ......................... 514/156 Lovhaug, all of Oslo (NO) 5,910,300 6/1999 Tournier et al. .................... 424/9.34 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (73) Assignee: Nycomed Imaging AS, Oslo (NO) 2 145 SOS 4/1994 (CA). (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 19 626 530 1/1998 (DE). patent is extended or adjusted under 35 O 727 225 8/1996 (EP). U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. WO91/15244 10/1991 (WO). WO 93/20802 10/1993 (WO). WO 94/07539 4/1994 (WO). (21) Appl. No.: 08/958,993 WO 94/28873 12/1994 (WO). WO 94/28874 12/1994 (WO). (22) Filed: Oct. 28, 1997 WO95/03356 2/1995 (WO). WO95/03357 2/1995 (WO). Related U.S. Application Data WO95/07072 3/1995 (WO). (60) Provisional application No. 60/049.264, filed on Jun. 7, WO95/15118 6/1995 (WO). 1997, provisional application No. 60/049,265, filed on Jun. WO 96/39149 12/1996 (WO). 7, 1997, and provisional application No. 60/049.268, filed WO 96/40277 12/1996 (WO). on Jun. 7, 1997. WO 96/40285 12/1996 (WO). (30) Foreign Application Priority Data WO 96/41647 12/1996 (WO). -

Comparison of the Efficacies of Proton Pump Inhibitors and H2 Receptor Antagonists in On-Demand Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

8 ORIGINAL ARTICLE COMPARISON OF THE EFFICACIES OF PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS AND H2 RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS IN ON-DEMAND TREATMENT OF GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE Nesibe Vardı1, Emine Köroglu2, Sabah Tüzün3, Can Dolapçıoğlu4, Reşat Dabak5 1Kilimli No: 8104005 Dikmeli Family Health Centre, Duzce, Turkey 2Department of Gastroenterology, Kartal Dr.Lütfi Kırdar Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey 3Department of Family Medicine, Kartal Dr. Lütfi Kırdar Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey Abstract Objective: On-demand treatment protocols in the maintenance treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are cost-efficient and easy-to-use treatments.This study aimed to compare the efficacies of H2 receptor antagonists (H2RA) and proton pump inhibitors (PPI) in on-demand treatment of GERD. Methods: Patients with persistent GERD symptoms were enrolledbetween January-November 2015 and were ran- domly separated into two equal groups. The patients in the first group were commenced on ranitidine 300 mg as H2RA and the patients in the second group were commenced on pantoprazole 40 mg. A 4-point Likert-type scale generated by the researchers was applied to evaluate the frequencies of reflux symptoms and their impacts on activities of life and business life. Results: Fifty-two patients were included, of whom 26 (50.0%) were in the PPI group and 26 (50.0%) were in the H2RA group. There were no significant differences between the study groups both before and after treatment in terms of the severity of reflux symptoms. There were significant decreases in the H2RA group in terms of the domains of retrosternal burning sensation, regurgitation, nausea and vomiting, and burping (p=0.036, p=0.027, p=0.020, and p=0.038, respectively). -

Dr. Reddy's – Recall of Ranitidine

Dr. Reddy’s – Recall of ranitidine • On October 23, 2019, Dr. Reddy’s announced the voluntary, consumer-level recall of prescription ranitidine due to potential contamination with N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA). • Dr. Reddy’s initially announced retail level recalls for prescription and OTC ranitidine in early October; however, the recall of prescription ranitidine products has been escalated to the consumer level. The recall of OTC ranitidine remains at the retail level. Prescription Ranitidine Capsules Recalled by Dr. Reddy’s Product Description NDC# Ranitidine 150 mg capsules, 60 count bottle 55111-129-60 Ranitidine 150 mg capsules, 500 count bottle 55111-129-05 Ranitidine 300 mg capsules, 30 count bottle 55111-130-30 Ranitidine 300 mg capsules, 100 count bottle 55111-130-01 • Refer to the Dr. Reddy’s announcement for a complete list of the OTC recalled ranitidine products. • Other manufacturers, including Apotex, Perrigo and Sanofi have recently announced retail level recalls of their OTC ranitidine products. • In September, Sandoz issued a consumer level recall of prescription ranitidine products. • These recalls follow a recent FDA statement about NDMA impurities detected in ranitidine medicines. • NDMA is classified as a probable human carcinogen based on results from laboratory tests. NDMA is a known environmental contaminant and found in water and foods, including meats, dairy products, and vegetables. • Ranitidine is an OTC and prescription drug. Ranitidine is an H2 (histamine-2) blocker, which decreases the amount of acid created by the stomach. OTC ranitidine is approved to prevent and relieve heartburn associated with acid ingestion and sour stomach. • Prescription ranitidine is approved for multiple indications, including treatment and prevention of ulcers of the stomach and intestines and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. -

Aciphex (Rabeprazole Sodium)

ACIPHEXÔ çç \ a-sc -**feks\ (rabeprazole sodium) Delayed-Release Tablets DESCRIPTION The active ingredient in ACIPHEXÔ Delayed-Release Tablets is rabeprazole sodium, a substituted benzimidazole that inhibits gastric acid secretion. Rabeprazole sodium is known chemically as 2-[[[4-(3-methoxypropoxy)-3-methyl-2- pyridinyl]-methyl] sulfinyl]-1H–benzimidazole sodium salt. It has an empirical formula of C18H20N3NaO3S and a molecular weight of 381.43. Rabeprazole sodium is a white to slightly yellowish-white solid. It is very soluble in water and methanol, freely soluble in ethanol, chloroform and ethyl acetate and insoluble in ether and n-hexane. The stability of rabeprazole sodium is a function of pH; it is rapidly degraded in acid media, and is more stable under alkaline conditions. The structural formula is: Na N O H3C O CH2 O CH3 S CH2 CH2 N CH2 N RABEPRAZOLE SODIUM ACIPHEXÔ is available for oral administration as delayed-release, enteric-coated tablets containing 20 mg of rabeprazole sodium. Inactive ingredients are mannitol, hydroxypropyl cellulose, magnesium oxide, low-substituted hydroxypropyl cellulose, magnesium stearate, ethylcellulose, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose phthalate, diacetylated monoglycerides, talc, titanium dioxide, carnauba wax, and ferric oxide (yellow) as a coloring agent. NDA 20-973 (AciphexÔ ) 1 Annotated Package Insert March 5, 1999 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism ACIPHEXTM delayed-release tablets are enteric-coated to allow rabeprazole sodium, which is acid labile, to pass through TM the stomach relatively intact. After oral administration of 20 mg ACIPHEX , peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) of rabeprazole occur over a range of 2.0 to 5.0 hours (Tmax). The rabeprazole Cmax and AUC are linear over an oral dose range of 10 mg to 40 mg. -

Proton Pump Inhibitors

Provider update Hot Tip: Proton pump inhibitors Your Amerigroup Community Care patients may experience a pharmacy claim rejection when prescribed nonpreferred products. To avoid additional steps or delays at the pharmacy, consider prescribing preferred products whenever possible. Utilization Management edits may apply to select preferred products. Coverage should be verified by reviewing the Preferred Drug List (PDL) on the Amerigroup provider website. The PDL is subject to change quarterly. Preferred products Nonpreferred products All brand and generic OTC strengths and All brand and generic prescription strengths formulations1 and formulations • OTC Zegerid (omeprazole-bicarbonate) • Zegerid (omeprazole-bicarbonate) OTC omeprazole-bicarbonate (generic OTC • Omeppi (omeprazole-bicarbonate) Zegerid) • Omeprazole-bicarbonate (generic Rx Zegerid) All brand and generic OTC product strengths and All brand and generic prescription product formulations1 See footnote for reference of strengths and formulations unless otherwise available OTC strengths3 noted • OTC esomeprazole DR (generic Nexium) • Aciphex (rabeprazole) • OTC lansoprazole DR (generic Prevacid) • Dexilant (dexlansoprazole) • OTC Nexium 24hr (esomeprazole) • Esomeprazole (generic Nexium) • OTC omeprazole (generic Prilosec) • Lansoprazole (Prevacid) • OTC Prevacid 24hr (lansoprazole) • Nexium (esomeprazole) • OTC Prilosec (omeprazole) • Omeprazole2 (generic Prilosec) • Pantoprazole (generic Protonix) • Prevacid (lansoprazole) • Prilosec (omeprazole) • Protonix (pantoprazole) • Rabeprazole -

Cimetidine As a Last Resort

Primary Care Guidance for Reviewing Patients on All Oral Formulations of Ranitidine (In response to Supply Disruption Alert dated 15 October 2019) Patients on ALL oral formulations of RANITIDINE Yes Can ranitidine be stopped or stepped down Stop / Try antacids to an antacid/alginate? No Can treatment be changed to a PPI? No Yes Patients who clinically should remain on ranitidine but has Children (Under 18 years old) now been withdrawn: On dual treatment of ranitidine and PPI and unsuitable for step-down ‘Simple’ GORD or Severe reflux o Consider maximising dose of PPI and trial without absence of oesophagitis, GI ranitidine if required. complex medical ulcer, complex On ranitidine for pre-chemotherapy prevention history medical history o This will be reviewed in secondary care. requiring acid On ranitidine due to C.diff risk with PPI reduction o Current or recent episode of C Difficile, or previously Stop ranitidine if had C Difficile and currently on antibiotics and are at possible and high risk. See recommendations below. recommend Allergic or intolerant to PPI or PPI contraindicated (e.g. dietary measures due to interstitial nephritis, acute kidney injury, previous hyponatraemia with PPI etc). See recommendations or antacids below. Always Check Weight Recommendations: Suitable PPI alternatives: 1. At time of publication (January 2020) Ranitidine is no longer available for supply. Consider if an H2 antagonist is still required. 1st line - Omeprazole capsule or dispersible tablets. Direction: Disperse tablet (or half of) in 5-10ml of water. For 5mg dose half the tablet before dispersing 2. If an H2 antagonist is required for children (over 1 year), consider switching to cimetidine as a last resort.