Malpaso Dance Company Is Filled with Information and Ideas That Support the Performance and the Study Unit You Will Create with Your Teaching Artist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics

Smith ScholarWorks Dance: Faculty Publications Dance 6-24-2013 “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs Part of the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Tomé, Lester, "“Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics" (2013). Dance: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs/5 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Dance: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] POSTPRINT “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Dance Chronicle 36/2 (2013), 218-42 https://doi.org/10.1080/01472526.2013.792325 This is a postprint. The published article is available in Dance Chronicle, JSTOR and EBSCO. Abstract: Alicia Alonso contended that the musicality of Cuban ballet dancers contributed to a distinctive national style in their performance of European classics such as Giselle and Swan Lake. A highly developed sense of musicality distinguished Alonso’s own dancing. For the ballerina, this was more than just an element of her individual style: it was an expression of the Cuban cultural environment and a common feature among ballet dancers from the island. In addition to elucidating the physical manifestations of musicality in Alonso’s dancing, this article examines how the ballerina’s frequent references to music in connection to both her individual identity and the Cuban ballet aesthetics fit into a national discourse of self-representation that deems Cubans an exceptionally musical people. -

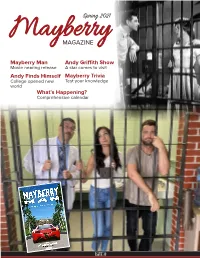

Spring 2021 Mayberry Magazine

Spring 2021 MayberryMAGAZINE Mayberry Man Andy Griffith Show Movie nearing release A star comes to visit Andy Finds Himself Mayberry Trivia College opened new Test your knowledge world What’s Happening? Comprehensive calendar ISSUE 30 Table of Contents Cover Story — Finally here? Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, work on the much ballyhooed Mayberry Man movie has continued, working around delays, postponements, and schedule changes. Now, the movie is just a few months away from release to its supporters, and hopefully, a public debut not too long afterward. Page 8 Andy finds himself He certainly wasn’t the first student to attend the University of North Carolina, nor the last, but Andy Griffith found an outlet for his creative talents at the venerable state institution, finding himself, and his career path, at the school. Page 4 Guest stars galore Being a guest star on “The Andy Griffith Show” could be a launching pad for young actors, and even already established stars sometimes wanted the chance to work with the cast and crew there. But it was Jean Hagen, driving a fast car and doing some smooth talking, who was the first established star to grace the set. Page 6 What To Do, What To Do… The pandemic put a halt to many shows and events over the course of 2020, but there might very well be a few concerts, shows, and events stirring in Mount Airy — the real-life Mayberry — this spring and summer. Page 10 SPRING 2021 SPRING So, You Think You Know • The Andy Griffith Show? Well, let’s see just how deep your knowledge runs. -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

Stephen M. Rooks

Stephen M. Rooks Vassar College 95 Vassar Road Box 743 Poughkeepsie, New York 12603 124 Raymond Avenue (845) 463-0020/416-8056 (cell) Poughkeepsie, New York 12604-0743 [email protected] (845) 437-7472 (845) 437-7818 (fax) [email protected] EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND B.A. (Cum Laude) Dartmouth College – Senior Fellow in Music 1977 The Mercersburg Academy 1973 French and German PROFESSIONAL WORK EXPERIENCE Professor of Dance and Resident Choreographer, Vassar College, 1996 to present Guest Artist-in-Residence, University of North Carolina School of the Arts, 2001 Lecturer in Dance, Howard University, 1993 – 1996 Instructor of Dance, Alvin Ailey American Dance Center, 1991 – 1996 Guest Instructor of Dance, Martha Graham Dance Center 1997 to present PRINCIPAL DANCER WITH MARTHA GRAHAM DANCE COMPANY, 1981 –1991; 1998, 2007 (Danced major roles in Graham repertory) DANCER WITH ALVIN AILEY II, 1980 – 1981 (performed in works by Alvin Ailey, Tally Beatty, Ulysses Dove, and Donald McKayle) PUBLICATIONS Rooks, Steve “An Interview with Ann Reinking: Teacher’s Wisdom” Dance Magazine, November 2006 TEACHING Undergraduate Courses: Beginning through Advanced Modern Dance (courses all informed by the codified Martha Graham technique – Vassar College), 1996 to present Graham Technique and Repertory (intermediate technique, repertory, and lectures on Martha Graham –Vassar College), 2003 to present Dance Composition/Craft of Choreography (working with students on the study, process, creation and performance of dance –Vassar College), 1996 to present Advanced -

Samba, Rumba, Cha-Cha, Salsa, Merengue, Cumbia, Flamenco, Tango, Bolero

SAMBA, RUMBA, CHA-CHA, SALSA, MERENGUE, CUMBIA, FLAMENCO, TANGO, BOLERO PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL DAVID GIARDINA Guitarist / Manager 860.568.1172 [email protected] www.gozaband.com ABOUT GOZA We are pleased to present to you GOZA - an engaging Latin/Latin Jazz musical ensemble comprised of Connecticut’s most seasoned and versatile musicians. GOZA (Spanish for Joy) performs exciting music and dance rhythms from Latin America, Brazil and Spain with guitar, violin, horns, Latin percussion and beautiful, romantic vocals. Goza rhythms include: samba, rumba cha-cha, salsa, cumbia, flamenco, tango, and bolero and num- bers by Jobim, Tito Puente, Gipsy Kings, Buena Vista, Rollins and Dizzy. We also have many originals and arrangements of Beatles, Santana, Stevie Wonder, Van Morrison, Guns & Roses and Rodrigo y Gabriela. Click here for repertoire. Goza has performed multiple times at the Mohegan Sun Wolfden, Hartford Wadsworth Atheneum, Elizabeth Park in West Hartford, River Camelot Cruises, festivals, colleges, libraries and clubs throughout New England. They are listed with many top agencies including James Daniels, Soloman, East West, Landerman, Pyramid, Cutting Edge and have played hundreds of weddings and similar functions. Regular performances in the Hartford area include venues such as: Casona, Chango Rosa, La Tavola Ristorante, Arthur Murray Dance Studio and Elizabeth Park. For more information about GOZA and for our performance schedule, please visit our website at www.gozaband.com or call David Giardina at 860.568-1172. We look forward -

RMAL Folkloric Recommendations

RMAL Folkloric Recommendations From the Usenet Newsgroup rec.music.afro-latin comes this list of recommended folkloric CD's (with an occasional cassette or LP). It is confined to Afro-Puerto Rican and Afro-Cuban "roots" music that is predominantly percussive/vocal; so it does not include the equally rich folkloric genre called son. Toward the end is a list of music and instruction videos and book/CD's. For those of you who are new to this genre, categories PUERTO RICO and CUBA have an asterisk * by those CDs which we think should be among your first buys. Our thanks for their generous help to Jorge Ginorio, Stan Ginn, Mike "Yambu" Doran, Zeno Okeanos and "Califa". Please note that for a few of these, the label and/or release date information is unknown. These are marked with (?). If you happen to know this information, please send me appropriate comments. PUERTO RICO Canario y su Grupo Plenas (Ansonia HGCD 1232) (?) Anthony Carrillo Mis Races (DRS Musical Productions DRMP2) 1997 Encuentro de Bomba y Plena al Acetato (MCB9203CD) 1992 - Modesto Cepeda *Races de Bomba y Plena (MCB9504CD) 1995 - Legado de Bomba y Plena (MCB9705CD) 1997 *William Cepeda & Bombazo (Blue Jackel BJAC 5027-2) 1998 Grupo Afro-Boricua Rafael Cepeda El Roble Mayor (Balele Records 010) 1996 Cortijo y Kako Ritmos y Cantos Callejeros (Ansonia CD 1477) 1970 Dr.Emanuel Dufrasne Puerto Rico Tambien Tiene Tamb - Book Copyright by Author, Gonzalez 1994 *Paracumbe Tamb (Ashe CD 2005) 1997 Somos Boricuas,Bomba y Plena en N.Y. (Henry Street 0003) Los Pleneros de la 21 1996 Los -

UNCORK YOUR CORN What I Think of for the Kindly Wish

Pa|e Two Chicago Sunday Tribune Looking at Hollywood Newfoundland's New Airport with Ed Sullivan A Big Help The Revolt to Ocean GANDAR LAKE o f Ann Flying BYy WAYNE THOMIS Sothern kNE OF THE least known airports in the world— By ED SULLIVAN o the Newfoundland flying Hollywood. field, situated in the midst of \S A RESULT of her fine job 500 square miles of virgin tim- in " Trade Winds/' which berland on the bleak little tri- she followed up with angle of rocks and scrub brush "Maisie," youthful and attrac- in the mouth of the bay of the tive Ann Sothern is the talk of St. Lawrence river—is destined the town. She should be the soon to become one of the ALTITUDE OF 540 FEET KEEPS RUNWAYS CONTAIN PAVING EQUAL talk of the town, because she world's most important aviation FIELD CLEAR OF FOG gambled $50,000 and a year of terminals. TO 100 MILES OF 20 FT. HIGHWAY her movie career on the propo- The field that has just been s i t i o n that Hollywood was completed after nearly three wrong and she was right. She years of heroic work by a crew Newfoundland's new airport as seen from the air. came close to starving, but she of more than 1,000 men, is to be won, and that, as the rabbit the jump-off point for most of or roughly 2,100 miles to C said, is a tale of importance. the east-bound trans-Atlantic don, the big international a Miss Sothern is a rarity in this airliners and the initial port of port of entry outside Londo town because she refuses to be arrival for most of the ocean air England. -

2016 - 2017 Season Passion

2016 - 2017 SEASON PASSION. DISCIPLINE. GRACE. Attributes that both ballet dancers and our expert group of medical professionals possess. At Fort Walton Beach Medical Center, each member of our team plays an important part in serving our patients with the highest quality care. We are proud to support the ballet in its mission to share the beauty and artistry of dance with our community. Exceptional People. Exceptional Care. 23666 Ballet 5.5 x 8.5.indd 1 8/26/2016 3:47:56 PM MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends: Thank you for joining us for our 47th season of the Northwest Florida Ballet. This year will be the most exciting yet, as we debut the Northwest Florida Ballet Symphony Orchestra led by renowned conductor and composer, David Ott. As a non-prot 501(c)(3) organization, NFB is highly regarded for providing world-class ballet performances, training students in the art of dance, and reaching out into our community through our educational endeavors. The introduction of the NFB Symphony Orchestra only further enriches our productions and programming, adding an unparalleled level of depth that Todd Eric Allen, NFB Artistic Director & CEO no other ballet company in our area can claim. In many ways, this depth showcases NFB as a cultural mosaic arranged to represent the best of the Emerald Coast. From the facility in downtown Fort Walton Beach where we train our students to the local family attending a ballet performance for the rst time, we recognize that every facet of who we are as an organization is part of this mosaic. -

HAVANA HOP Fulfills the Following Ohio and Atw Victoria Theatre Association

2015-2016 Resource Guide Written, Choreographed, and Performed by Paige Hernandez APRIL 27, 2016 9:30 & 11:30 A.M. • VICTORIA THEATRE The Frank M. FOUNDATION www.victoriatheatre.com Curriculum Connections You will find these icons listed in the resource guide next to the activities that indicate curricular elcome to the 2015-2016 Frank connections. Teachers and parents are encouraged to adapt all of the activities included in an M. Tait Foundation Discovery Series appropriate way for your students’ age and abilities. HAVANA HOP fulfills the following Ohio and atW Victoria Theatre Association. We are very National Education State Standards and Benchmarks for grades 2-8: excited to be your partner in providing English/Language Arts Standards Ohio Department of Education professional arts experiences to you and Grade 2- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.2.2, CCSS.ELA-Literacy. your students! Drama/Theatre & Dance Standards RL.2.3, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL2.4, CCSS.ELA-Literacy. Drama/Theatre Standards RL2.5, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL2.6 I am excited for students in Dayton to Grade 2- 1CE-7CE, 1PR-3PR, 1RE-6RE Grade 3- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.3.2, CCSS.ELA-Literacy. experience HAVANA HOP! Ms. Hernandez Grade 3- 1CE-5CE, 1PR-6PR, 1RE-5RE RL.3.3, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.3.5, CCSS.ELA-Literacy. is a multifaceted artist, who is known Grade 4- 1CE-6CE, 1PR-7PR, 1RE-5RE RL.3.6 for her innovative fusion of poetry, hip Grade 5- 1CE-5CE, 1PR-5PR, 1RE-5RE Grade 4- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.4.2, CCSS.ELA-Literacy. -

How Cuba Produces Some of the Best Ballet Dancers in the World by Noël Duan December 14, 2015 9:01 PM

http://news.yahoo.com/how-cuba-produces-some-of-the-best-ballet-dancers-020100947.html How Cuba Produces Some of the Best Ballet Dancers in the World By Noël Duan December 14, 2015 9:01 PM Recent graduates of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba School performing at the National Theater of Cuba in Havana in February 2015. (Photo: Getty Images) This story is part of a weeklong Yahoo series marking one year since the opening of relations between the United States and Cuba. Cuba is well known for many forms of dance, from the mambo and the tango to salsa, the cha- cha and the rumba. But only ballet enthusiasts know that the dance form is one of the country’s biggest cultural exports. In Cuba, ballet is just as popular as baseball, a sport where players from the Cuban national team regularly defect to the major leagues in the United States. Unlike in the United States, where ballet is generally considered highbrow art and Misty Copeland is the only ballerina with a household name, the Cuban government funds ballet training and subsidizes tickets to ballet performances. “Taxi drivers know who the principal dancers are,” Lester Tomé, a dance professor at Smith College and former dance critic in Cuba and Chile, tells Yahoo Beauty. Like Cuban baseball players, Cuban ballet dancers have made international marks around the world, from Xiomara Reyes, the recently retired principal dancer at New York City’s American Ballet Theatre to London’s English National Ballet ballet master Loipa Araújo, regarded as one of the “four jewels of Cuban ballet.” In September 2005, Erika Kinetz wrote in the New York Times that “training, especially Cuban training, has been a key driver of the Latinization of ballet,” an important note, considering that European ballet companies dominated the dance world for decades. -

DENNIS KOOKER President, Global Digital Business and U.S

Before the UNITED STATES COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Library of Congress Washington, D.C. ) In re ) ) DETERMINATION OF ROYALTY ) DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0001-WR RATES AND TERMS FOR ) (2016-2020) EPHEMERAL RECORDING AND ) DIGITAL PERFORMANCE OF SOUND ) RECORDINGS (WEB IV) ) ) TESTIMONY OF DENNIS KOOKER President, Global Digital Business and U.S. Sales, Sony Music Entertainment PUBLIC VERSION Witness for SoundExchange, Inc. PUBLIC VERSION TESTIMONY OF DENNIS KOOKER BACKGROUND My name is Dennis Kooker. I have been employed in the recorded music business for approximately 20 years. Since 2012, I have served as President, Global Digital Business and U.S. Sales, for Sony Music Entertainment (“Sony Music”), a wholly owned subsidiary of Sony Corporation, and currently the second largest record company in the United States. In this capacity, I am responsible for overseeing all aspects of the Global Digital Business Group and the U.S. Sales Group. The Global Digital Business Group handles business and partner development and strategy for the digital business around the world. The U.S. Sales Group oversees sales initiatives on behalf of each of Sony Music’s various label groups in the United States. The areas within the organization that report to me include Business Development & Strategy, Partner Development, Digital Finance, Digital Business & Legal Affairs, U.S. Sales, and Sony Music’s distribution service company, RED Distribution. From 2007-2012, I held two different positions at Sony Music. First, I was Executive Vice President, Operations, for the Global Digital Business and U.S. Sales, and oversaw physical sales, aspects of marketing and finance for the division, new product development, and customer relationship management activities in relation to Sony Music’s artist websites.