Democratic Republic of the Congo –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year in Review 2008

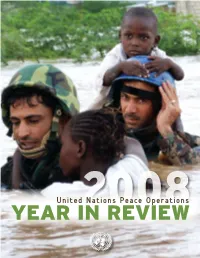

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

With Effect from 1 April 2012 Through 30 June 2012

List of locations where payment of danger pay has been approved' with effect from 1 April 2012 through 30 June 2012: AFGHANISTAN CONGO, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF - North Kivu Province, South Kivu Province, Orientale Province - (only Bas Uele, Haut Uele and Ituri Districts), Maniema Province ETHIOPIA - Somali Region IRAQ - Entire country except Erbil KENYA - North Eastern Province (Garissa, Dadaab, Mandera, Wajir, Ijara) LEBANON - South Lebanon (UNIFIL Area of Operations, except the Tyre pocket) PAKISTAN - Balochistan Province, Khyber Pakhtunkhawa Province (formerly, North-West Frontier Province) and Federally Administrated Tribal Areas SOMALIA SOUTH SUDAN - Unity State, Upper Nile State, Jonglei State, Warrap State (except Tonji South county), in Lakes State (only Awerial, Yirol East, Rumbek Centre, Rumbek North and Rumbek East counties), in Northern Bar El Gazal State (only Aweil East and Aweil North counties), in Western Bar El Gazal State (all locations north of the road Kafia-Gabir-Kosho-Raja, excluding Raga town), Western Equatoria (only all locations south of the road Morobo-Yei-Maridi- Yambio-Nadi-Tambura, except Yambio town) SUDAN - the Darfurs (West, South and North Darfur), Abyei Administered Area, South Kordofan State and Blue Nile State SYRIA ARAB REPUBLIC - Entire country except Damascus (city boundaries) and UNDOF Area of Operations • YEMEN Addendum Please note that in addition to the approved locations above, on 3 July 2012, Danger Pay was also approved for the location below with retroactive effective date of 1 to 30 June 2012: ® Damascus, Syria. -

A Life of Fear and Flight

A LIFE OF FEAR AND FLIGHT The Legacy of LRA Brutality in North-East Democratic Republic of the Congo We fled Gilima in 2009, as the LRA started attacking there. From there we fled to Bangadi, but we were confronted with the same problem, as the LRA was attacking us. We fled from there to Niangara. Because of insecurity we fled to Baga. In an attack there, two of my children were killed, and one was kidnapped. He is still gone. Two family members of my husband were killed. We then fled to Dungu, where we arrived in July 2010. On the way, we were abused too much by the soldiers. We were abused because the child of my brother does not understand Lingala, only Bazande. They were therefore claiming we were LRA spies! We had to pay too much for this. We lost most of our possessions. Once in Dungu, we were first sleeping under a tree. Then someone offered his hut. It was too small with all the kids, we slept with twelve in one hut. We then got another offer, to sleep in a house at a church. The house was, however, collapsing and the owner chased us. He did not want us there. We then heard that some displaced had started a camp, and that we could get a plot there. When we had settled there, it turned out we had settled outside of the borders of the camp, and we were forced to leave. All the time, we could not dig and we had no access to food. -

DR-CONGO December 2013

COUNTRY REPORT: DR-CONGO December 2013 Introduction: other provinces are also grappling with consistently high levels of violence. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DR-Congo) is the sec- ond most violent country in the ACLED dataset when Likewise, in terms of conflict actors, recent international measured by the number of conflict events; and the third commentary has focussed very heavily on the M23 rebel most fatal over the course of the dataset’s coverage (1997 group and their interactions with Congolese military - September 2013). forces and UN peacekeepers. However, while ACLED data illustrates that M23 has constituted the most violent non- Since 2011, violence levels have increased significantly in state actor in the country since its emergence in April this beleaguered country, primarily due to a sharp rise in 2012, other groups including Mayi Mayi militias, FDLR conflict in the Kivu regions (see Figure 1). Conflict levels rebels and unidentified armed groups also represent sig- during 2013 to date have reduced, following an unprece- nificant threats to security and stability. dented peak of activity in late 2012 but this year’s event levels remain significantly above average for the DR- In order to explore key dynamics of violence across time Congo. and space in the DR-Congo, this report examines in turn M23 in North and South Kivu, the Lord’s Resistance Army Across the coverage period, this violence has displayed a (LRA) in northern DR-Congo and the evolving dynamics of very distinct spatial pattern; over half of all conflict events Mayi Mayi violence across the country. The report then occurred in the eastern Kivu provinces, while a further examines MONUSCO’s efforts to maintain a fragile peace quarter took place in Orientale and less than 10% in Ka- in the country, and highlights the dynamics of the on- tanga (see Figure 2). -

Drc): Case Studies from Katanga, Ituri and Kivu

CONFLICT BETWEEN INDUSTRIAL AND ARTISANAL MINING IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO (DRC): CASE STUDIES FROM KATANGA, ITURI AND KIVU Ruben de Koning Introduction The mining sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is widely regarded as the key engine for post-conflict reconstruction. To attract for- eign investment, the government in 2002 enacted a new mining code that makes it easier for foreign companies to obtain industrial mining titles. Within a few years exploration concessions covered about a third of the country. Meanwhile, exploitation rights to the most important proven deposits were converted to new joint-ventures between foreign investors and Congolese state mining companies. The rapid attribution of min- ing titles has, however, not lead to a resumption of industrial mining on the scale the central government and its foreign donors had hoped for. Apart from a few copper and cobalt mines in the southern Katanga prov- ince, mineral production in the rest of the country, but also in Katanga, remains largely artisanal. Artisanal mining employs up to two million people across the country and largely takes place on concessions where industrial mining is supposed happen (Wold Bank 2009). In many of these artisanal mining areas and particularly in the eastern DRC state functions have almost completely eroded during two consecutive civil wars. Arti- sanal miners often work in dangerous conditions and are forced to pay numerous illegal taxes or to work for the military and rebel forces that control mines. At the same time, the local power complexes that emerged around artisanal mining operations have withheld large scale industrial investment, thereby preventing displacement of artisanal miners from concessions. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic Main objectives Impact • UNHCR provided international protection to some In 2005, UNHCR aimed to strengthen the protection 204,300 refugees in the DRC of whom some 15,200 framework through national capacity building, registra- received humanitarian assistance. tion, and the prevention of and response to sexual and • Some of the 22,400 refugees hosted by the DRC gender-based violence; facilitate the voluntary repatria- were repatriated to their home countries (Angola, tion of Angolan, Burundian, Rwandan, Ugandan and Rwanda and Burundi). Sudanese refugees; provide basic assistance to and • Some 38,900 DRC Congolese refugees returned to locally integrate refugee groups that opt to remain in the the DRC, including 14,500 under UNHCR auspices. Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); prepare and UNHCR monitored the situation of at least 32,000 of organize the return and reintegration of DRC Congolese these returnees. refugees into their areas of origin; and support initiatives • With the help of the local authorities, UNHCR con- for demobilization, disarmament, repatriation, reintegra- ducted verification exercises in several refugee tion and resettlement (DDRRR) and the Multi-Country locations, which allowed UNHCR to revise its esti- Demobilization and Reintegration Programme (MDRP) mates of the beneficiary population. in cooperation with the UN peacekeeping mission, • UNHCR continued to assist the National Commission UNDP and the World Bank. for Refugees (CNR) in maintaining its advocacy role, urging local authorities to respect refugee rights. UNHCR Global Report 2005 123 Working environment Recurrent security threats in some regions have put another strain on this situation. -

Dismissed! Victims of 2015-2018 Brutal Crackdowns in the Democratic Republic of Congo Denied Justice

DISMISSED! VICTIMS OF 2015-2018 BRUTAL CRACKDOWNS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DENIED JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: “Dismissed!”. A drawing by Congolese artist © Justin Kasereka (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 62/2185/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND: POLITICAL CRISIS 10 3.1 ATTEMPTS TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION 10 3.2 THE « GLISSEMENT »: THE LONG-DRAWN-OUT ELECTORAL PROCESS 11 3.3 ELECTIONS AT LAST 14 3.3.1 TIMELINE 15 4. VOICES OF DISSENT MUZZLED 19 4.1 ARBITRARY ARRESTS, DETENTIONS AND SYSTEMATIC BANS ON ASSEMBLIES 19 4.1.1 HARASSMENT AND ARBITRARY ARRESTS OF PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS AND OPPONENTS 20 4.1.2 SYSTEMATIC AND UNLAWFUL BANS ON ASSEMBLY 21 4.2 RESTRICTIONS OF THE RIGHT TO SEEK AND RECEIVE INFORMATION 23 5. -

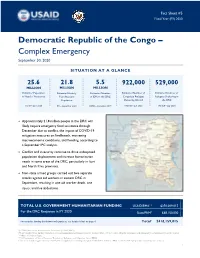

DRC Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #5 09.30.2020

Fact Sheet #5 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Complex Emergency September 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 25.6 21.8 5.5 922,000 529,000 MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Population Estimated Acutely Estimated Number Estimated Number of Estimated Number of in Need of Assistance Congolese Refugees Refugees Sheltering in Food Insecure of IDPs in the DRC Population Sheltering Abroad the DRC OCHA – June 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 IPC – September 2020 OCHA – December 2019 Approximately 21.8 million people in the DRC will likely require emergency food assistance through December due to conflict, the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on livelihoods, worsening macroeconomic conditions, and flooding, according to a September IPC analysis. Conflict and insecurity continue to drive widespread population displacement and increase humanitarian needs in some areas of the DRC, particularly in Ituri and North Kivu provinces. Non-state armed groups carried out two separate attacks against aid workers in eastern DRC in September, resulting in one aid worker death, one injury, and five abductions. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $350,009,015 For the DRC Response in FY 2020 State/PRM3 $68,150,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total4 $418,159,015 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance and emergency food assistance from the former Office of Food for Peace. 3 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 4 This total includes approximately $23,833,699 in supplemental funding through USAID/BHA and State/PRM for COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. -

Mapping Conflict Motives: M23

Mapping Conflict Motives: M23 1 Front Cover image: M23 combatants marching into Goma wearing RDF uniforms Antwerp, November 2012 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 1. Background 5 2. The rebels with grievances hypothesis: unconvincing 9 3. The ethnic agenda: division within ranks 11 4. Control over minerals: Not a priority 14 5. Power motives: geopolitics and Rwandan involvement 16 Conclusion 18 3 Introduction Since 2004, IPIS has published various reports on the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Between 2007 and 2010 IPIS focussed predominantly on the motives of the most significant remaining armed groups in the DRC in the aftermath of the Congo wars of 1996 and 1998.1 Since 2010 many of these groups have demobilised and several have integrated into the Congolese army (FARDC) and the security situation in the DRC has been slowly stabilising. However, following the November 2011 elections, a chain of events led to the creation of a ‘new’ armed group that called itself “M23”. At first, after being cornered by the FARDC near the Rwandan border, it seemed that the movement would be short-lived. However, over the following two months M23 made a remarkable recovery, took Rutshuru and Goma, and started to show national ambitions. In light of these developments and the renewed risk of large-scale armed conflict in the DRC, the European Network for Central Africa (EURAC) assessed that an accurate understanding of M23’s motives among stakeholders will be crucial for dealing with the current escalation. IPIS volunteered to provide such analysis as a brief update to its ‘mapping conflict motives’ report series. -

NO19-Digital Media in Central Africa.Indd

REFERENCE SERIES NO. 19 MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: NEWS AND NEW MEDIA IN CENTRAL AFRICA. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES By Marie-Soleil Frère December 2012 News and New Media in Central Africa. Challenges and Opportunities WRITTEN BY Marie-Soleil Frère1 Th e Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa. Rwanda and Burundi are among the continent’s smallest states. More than just neighbors, these three countries are locked together by overlapping histories and by extreme political and economic challenges. Th ey all score very low on the United Nations’ human development index, with DRC and Burundi among the half-dozen poorest and most corrupt countries in the world. Th ey are all recovering uncertainly from confl icts that involved violence on an immense scale, devastating communities and destroying infrastructure. Th eir populations are overwhelmingly rural and young. In terms of media, radio is by far the most popular source of news. Levels of state capture are high, and media quality is generally poor. Professional journalists face daunting obstacles. Th e threadbare markets can hardly sustain independent outlets. Amid continuing communal and political tensions, the legacy of “hate media” is insidious, and upholding journalism ethics is not easy when salaries are low. Ownership is non-transparent. Telecoms overheads are exorbitantly high. In these conditions, new and digital media—which fl ourish on consumers’ disposable income, strategic investment, and vibrant markets—have made a very slow start. Crucially, connectivity remains low. But change is afoot, led by the growth of mobile internet access. 1. Marie-Soleil Frère is Senior Research Associate at the National Fund for Scientifi c Research (Belgium) and Director of the Research Center in Information and Communication (ReSIC) at the University of Brussels. -

DRC Humanitarian Situation Report

DRC Humanitarian Situation Report Photo: UNICEF DRC Oatway July 2019 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 1,260,000*Internally Displaced Persons • In July, UNICEF’s Rapid Response to Movements of Population (IDPs) (HPR 2019) (RRMP) mechanism provided 95,814 persons with essential * Estimate for 2019 household items and shelter materials 7,500,000 children in need of humanitarian assistance (OCHA, HRP 2019) • Multiple emergencies in the provinces of Ituri, South Kivu, Kwango, and Mai Ndombe (Yumbi territory) are heavily underfunded. This gap impacts UNICEF’s response to the 1,400,000 children are suffering from Severe emergencies and prevent children from accessing their basic Acute malnutrition (DRC Nutrition Cluster, January 2019) rights, such as education, child protection, and nutrition 13,542 cases of cholera reported since January st • Ebola outbreak: as of 31 of July 2019, 2,687 total cases of 2019 (Ministry of Health) Ebola, 2,593 confirmed cases and 1,622 deaths linked to Ebola have been recorded in the provinces of North Kivu and 137,154 suspect cases of measles reported since Ituri. January (Ministry of Health) UNICEF Appeal 2019 UNICEF’s Response with Partners US$ 326 Million 25% of required funds available UNICEF Sector/Cluster 2019 DRC HAC FUNDING UNICEF Total Cluster Total STATUS* Target Results* Target Results* Funds received Nutrition: # of children with SAM 911,907 124,888 986,708 365,444 current year: Carry- admitted for therapeutic care $38.1M forward Health: # of children in amount humanitarian situations 1,028,959 1,034,550 -

Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Review Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Jean-Claude Makenga Bof 1,* , Fortunat Ntumba Tshitoka 2, Daniel Muteba 2, Paul Mansiangi 3 and Yves Coppieters 1 1 Ecole de Santé Publique, Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Route de Lennik 808, 1070 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 2 Ministry of Health: Program of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) for Preventive Chemotherapy (PC), Gombe, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] (F.N.T.); [email protected] (D.M.) 3 Faculty of Medicine, School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa (UNIKIN), Lemba, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-493-93-96-35 Received: 3 May 2019; Accepted: 30 May 2019; Published: 13 June 2019 Abstract: Here, we review all data available at the Ministry of Public Health in order to describe the history of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control (NPOC) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Discovered in 1903, the disease is endemic in all provinces. Ivermectin was introduced in 1987 as clinical treatment, then as mass treatment in 1989. Created in 1996, the NPOC is based on community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI). In 1999, rapid epidemiological mapping for onchocerciasis surveys were launched to determine the mass treatment areas called “CDTI Projects”. CDTI started in 2001 and certain projects were stopped in 2005 following the occurrence of serious adverse events. Surveys coupled with rapid assessment procedures for loiasis and onchocerciasis rapid epidemiological assessment were launched to identify the areas of treatment for onchocerciasis and loiasis.