Livelihoods of Small-Scale Fishers of Struisbaai: Implications for Marine Protected Area Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape-Agulhas-WC033 2020 IDP Amendment

REVIEW AND AMENDMENTS TO THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2020/21 CAPE AGULHAS MUNICIPALITY REVIEW AND AMENDMENTS TO THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2020/21 29 My 2020 Together for excellence Saam vir uitnemendheid Sisonke siyagqwesa 1 | P a g e REVIEW AND AMENDMENTS TO THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2020/21 SECTIONS THAT ARE AMENDED AND UPDATED FOREWORD BY THE EXECUTIVE MAYOR (UPDATED)............................................................................ 4 FOREWORD BY THE MUNICIPAL MANAGER (UPDATED) ..................................................................... 5 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 INTRODUCTION TO CAPE AGULHAS MUNICIPALITY (UPDATED) ......................................... 7 1.2 THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN AND PROCESS ......................................................... 8 1.2.4 PROCESS PLAN AND SCHEDULE OF KEY DEADLINES (AMENDMENT) ........................... 8 1.3 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION STRUCTURES, PROCESSES AND OUTCOMES .................................. 9 1.3.3 MANAGEMENT STRATEGIC WORKSHOP (UPDATED) .................................................... 10 2. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND INTERGOVERNMENTAL STRATEGY ALIGNMENT ................................. 11 2.2.2 WESTERN CAPE PROVINCIAL PERSPECTIVE (AMENDED) ............................................. 11 3 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS............................................................................................................... -

We Believe in Kleinmond More About Xplorio

November 2017 WE BELIEVE IN KLEINMOND What is this Report? If you’re excited about growing your town’s online presence then this report is going to really make your day. Xplorio Kleinmond has been exploding online but don’t just take our word for it, we’ve got phenomenal results for you to browse below. 1 Xpli Kleinmond Online Goh We reached 2,318 people searching for information about Kleinmond online this month. That's roughly 74 potential customers interested in your town every day. When looking at data from the previous years, we've experienced a 102% growth in users. 2016 January - October 2017 January - October 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 2 Xpli Kleinmond’ Top Ranking Pile THINGS TO DO ACCOMMODATION BUSINESSES PLACES TO EAT JOE LATEGAN FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHY THE WILD FIG GUEST HOUSE PAM GOLDING KABELJOE'S RESTAURANT BIG TREE MARKET PINO MARI HOLIDAY HOME NO 16 MILKWOOD EMBROIDERY CUP'A CAFE KOGELBERG NATURE RESERVE XANSKE'S PLACE KLEINMOND CYCLES STOEP CAFE PALMIET RIVER MTB ROUTE FORGET-ME-NOT POINT OF GRACE BISTRO 14 3 Xpli Kleinmond’ Current Goh ACCOMMODATIONS THINGS TO DO CUSTOMERS 74 LEADS 24 CUSTOMERS 115 LEADS 37 PLACES TO EAT BUSINESSES CUSTOMERS 85 LEADS 28 CUSTOMERS 662 LEADS 218 * Customers are dened as website visitors with the intent of nding a business. **Leads are customers who enquire via phone or email with a specic business. ***Data provided above are for the last 3 months. ~93% of Kleinmond Businesses are already on Xplorio. 220 235 * Numbers derived from statssa.gov.za 4 Ho doe Xpli promote Kleinmond? We publish your town’s content on our social media platforms, driving more trac to Xplorio Kleinmond pages and proles. -

Overberg District Municipality Climate Change Summary Report

Overberg District Municipality Climate Change Adaptation Summary Report March 2018 Version 2 Developed through the Local Government Climate Change Support Program 1 Report Submitted to GIZ Office, Pretoria Procurement Department Hatfield Gardens, Block C, Ground Floor 333 Grosvenor Street Hatfield Pretoria Report Submitted by +27 (0)31 8276426 [email protected] www.urbanearth.co.za This project is part of the International Climate Initiative (IKI) and is supported by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH on behalf of The Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB). Version Control Version Date Submitted Comments 1 1 November 2017 Draft version with desktop review information . 2 15 March 2017 Methodology, Key District Indicators and Sector Snapshots moved from the main body of the report to Annexures. 2 Contents 1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Biodiversity and Environment ......................................................................................... 8 1.2 Coastal and Marine ........................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Human Health ................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Disaster Management, Infrastructure and Human Settlements ................................... 9 1.5 Water ................................................................................................................................ -

Economic State and Growth Prospects of the 12 Proclaimed Fishing Harbours in the Western Cape

Department of the Premier Report on the Economic and Socio- Economic State and Growth Prospects of the 12 Proclaimed Fishing Harbours in the Western Cape November 2012 Final consolidated report TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ i 1 Introduction and purpose ................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project approach ..................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Project background ................................................................................................. 3 2 Policy and institutional context ........................................................................ 4 2.1 Historical context ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Local government context ....................................................................................... 4 2.3 Policy governing fishing harbours ........................................................................... 6 2.4 Key legislation relevant to fishing harbour governance............................................ 8 2.5 Previous investigations into harbour governance and management models to promote local socio-economic gains ..................................................................... 10 3 Assessment of fishing harbours and communities ...................................... 15 3.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... -

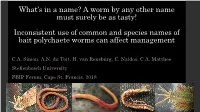

A Worm by Any Other Name Must Surely Be As Tasty! Inconsistent Use

What’s in a name? A worm by any other name must surely be as tasty! Inconsistent use of common and species names of bait polychaete worms can affect management C.A. Simon, A.N. du Toit, H. van Rensburg, C. Naidoo, C.A. Matthee Stellenbosch University FBIP Forum, Cape St. Francis, 2018 Polychaetes used as bait, according to Dept. of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Species Common name All species of the genus Bloodworm Arenicola All marine species of the Any seaworm, including phyla Platyhelminthes, polychaete, wonder shingle, Nemertea, Sipunculida and moonshine, coral, pot, Annelida, but excluding the pudding, rock, tape & genera Nereis, Pseudonereis flatworms, but excluding and Gunnarea mussel worms and Cape reef- worms Which polychaete species are used: field guides Common name Species name according to Species name according to field DAFF guides # +*$ Bloodworm Arenicola loveni Arenicola loveni 1998 Wooldridge * ; Cape reef-worm Gunnarea gaimardi (capensis) Gunnarea gaimardi (capensis) $ Whibley 2003 The South The 2003 Whibley Case worm X Diopatra cuprea+ # Coral worm Gunnarea gaimardi (capensis) Eunice aphroditois* Errant worm Eunice aphroditois X Estuarine wonderworm X Marphysa elityeni$ Moonlight#/moonshine Arabella iricolor X worm Pseudonereis podocirra Mussel worm# Pseudonereis podocirra (variegata) +*$ of life marine tothe guide A Oceans. Two 2010 etal. Branch (variegata) $ ; Pot, pudding, shingle Nephtys, Lumbrineris spp X worm Rock worm Pseudonereis podocirra (variegata) X Wonderworm# Marphysa elityeni Eunice aphroditois$ Day 1969 A guide to marine life on South African shores African South on life tomarine guide A 1969 Day + Field guide to the Eastern & Southern Cape coasts; Cape Southern & Eastern tothe guide Field Fisherman African Africa southern Names of bait polychaetes according to literature P. -

Legend Swellendam Sub District of Overberg Magisterial District

Swellendam Sub district of Overberg Magisterial District 29 NOG WAT 28 KLIP 193 1 KLIPGAT 6 UVR KRAAL 69 11 JOHANNISVILLE 3 61 2 63 STINKFONTEIN PIKSTEEL 152 7 BEAVER 56 70 KUIL 10 55 EYERPOORT 4 307 CREEK 311 BYLSHOEK 73 GANSKOP Kannaland WORCESTER RATELFONTEIN HIGHLANDS 81 Brak HONDEWATER 136 195 71 Sub district BRAK 529 OKKERSKRAAL RIVIER 5 200 R UV318 Langeberg GANNALEEGTE 13 T 137 SPITZ ou BELLAIR DOORNRIVIER w Sub district 241 KOP 198 s OORLOGS 626 20 681 A 507 NORREE KLOOF 118 GATS 13 RIETVALLEI RIETKUIL KRAAL 138 LADISMITH 308 MONTAGU MONTAGU 654 18 132 225 133 V 217 KEURFONTEIN i Montagu MC 625 n k VENTERS POORTFONTEIN KAREE ROBERTSON 140 622 LADISMITH Montagu SAPS ABRIKOOS MUUR 141 36 21 NES 257 ASHTON KLOOF 143 DWARS DEUR 263 218 2 290 30 KLEINBERG 139 R6 MAATSKRAAL Robertson 192 BARRYDALE 678 287 SAPS Ashton PC UV 265 255 UVR 318 6 PAPPEKUILS 62 2 Groot HERMANUS Robertson MC 256 0 Ashton SAPS FONTEIN 61 581 R6 RIET KRAAL 258 UV MARTHINUS UV KROMME R GOREE 158 VALLEI 167 KLIPKUIL POORTJIES 3 20 rs R STEPHAANS SKIETHOEK KLOOF 11 2 e UV3 168 KLOOF 169 578 3 is 17 ANNEX 170 27 194 e KLOOF 117 309 K UITNOOD DOORNRIVIERS 129 271 RIET 60 VALLEY 30 3 BRAND 173 54 59 RIVIER RIVIER 7 181 244 Barrydale BOSJEMAN`S 711 MIDDEL VAN 644 KLIP Barrydale PC SAPS PHISANTE WOLVENDRIFT PAD 173 DUIWEHOKS FONTEIN 577 BERG 136 183 693 ou 125 Bonnievale PC HET GOED Trad RIVIER 77 Mcgregor SAPS McGregor PC Bonnievale JAN GELOOF 70 TRADAUW 69 MOERASRIVIER 76 SAPS HARMENS 171 664 ZOUT PANS GAT 179 MCGREGOR ZUURPLAATS 71 LOT A 82 FOREST 77 161 DOORNS 165 -

We Believe in Riviersonderend More About Xplorio

August 2017 WE BELIEVE IN RIVIERSONDEREND What is this Report? If you’re excited about growing your town’s online presence then this report is going to really make your day. Xplorio Riviersonderend has been exploding online but don’t just take our word for it, we’ve got phenomenal results for you to browse below. 1 Xpli Riviersonderend Online Goh We reached 597 people searching for information about Riviersonderend online this month. That's roughly 19 potential customers interested in your town every day. When looking at data from the previous years, we've experienced a 210% growth in users. 2016 January - July 2017 January - July 0 1.000 2.000 3.000 4.000 5.000 6.000 7.000 8.000 2 Xpli Riviersonderend’ Top Ranking Pile THINGS TO DO ACCOMMODATION BUSINESSES PLACES TO EAT KHOMEESDRIF DANKE GUEST HOUSE MARI'S FUDGE RSE FISHERIES BLUE CRANE RUN AND RIDE DASBERG GUEST HOUSE OLD FARM SHOP WHERE PEOPLE COME TOGETHER LAMORE HEALTH AND VORTEX OPEN SOURCE JONGENSKLOOF COUNTRY RETREAT SKINCARE SALON VN'DESDEN BAKERY RIVIERSONDEREND KERSMARK RIVIERSONDEREND 4X4 OU MEUL BAKERY STEERS RIVIERSONDEREND 3 Xpli Riviersonderend’ Current Goh ACCOMMODATIONS THINGS TO DO CUSTOMERS 41 LEADS 13 CUSTOMERS 40 LEADS 13 PLACES TO EAT BUSINESSES CUSTOMERS 38 LEADS 12 CUSTOMERS 91 LEADS 30 * Customers are dened as website visitors with the intent of nding a business. **Leads are customers who enquire via phone or email with a specic business. ***Data provided above are for the last 3 months. ~87% of Riviersonderend Businesses are already on Xplorio. 86 98 * Numbers derived from statssa.gov.za 4 Ho doe Xpli promote Riviersonderend? We publish your town’s content on our social media platforms, driving more trac to Xplorio Riviersonderend pages and pro- Social Media We work on achieving rst page results on search engines for all business categories that are relevant to Xplorio Riviersonderend . -

Agulhas National Park State of Knowledge

AGULHAS NATIONAL PARK STATE OF KNOWLEDGE Contributors: T. Kraaij, N. Hanekom, I.A. Russell, R.M. Randall SANParks Scientific Services, Garden Route (Rondevlei Office), PO Box 176, Sedgefield, 6573 Last updated: 16 January 2008 Disclaimer This report has been produced by SANParks to summarise information available on a specific conservation area. Production of the report, in either hard copy or electronic format, does not signify that: . the referenced information necessarily reflect the views and policies of SANParks; . the referenced information is either correct or accurate; . SANParks retains copies of the referenced documents; . SANParks will provide second parties with copies of the referenced documents. This standpoint has the premise that (i) reproduction of copywrited material is illegal, (ii) copying of unpublished reports and data produced by an external scientist without the author’s permission is unethical, and (iii) dissemination of unreviewed data or draft documentation is potentially misleading and hence illogical. This report should be cited as: Kraaij T, Hanekom N, Russell IA & Randall RM. 2009. Agulhas National Park – State of Knowledge. South African National Parks. TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTE: TEXT IN SMALL CAPS PERTAINS TO THE MARINE COMPONENT OF THE AGULHAS AREA Abbreviations used 3 Abbreviations used............................................................................................................4 1. ACCOUNT OF AREA...................................................................................................4 -

Integrated Transport Plan for Overberg

REVIEW OF OVERBERG DITP DISTRICT INTEGRATED TRANSPORT PLAN FOR OVERBERG DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY FINAL DRAFT March 2016 5th Floor, Imperial Terraces Carl Cronje Drive Tyger Waterfront Bellville, 7530 (021) 914 6211 (T) (021) 914 7403 (F) e-mail: [email protected] i SUMMARY SHEET Report Type DITP Report Title District Integrated Transport Plan for Overberg Location Overberg, Western Cape Client Western Cape Government Reference Number ITS 3450 Lynne Pretorius, Zaida Tofie, Wilhelm de Klerk, Eva Louw, Nick Platte, Project Team Stephen van der Sluys Contact Details Tel: 021 914 6211 Date March 2016 Report Status Final Report File Name G:\3450 Review of Overberg ITP\12 Reports\Draft\DITP\3450_Review of Overberg ITP_DITP Report_zt_WDK_ 2016-03-31 Final Draft.docx ii PROJECT TEAM CONTACT DETAILS Company Contact person Email Western Cape Mario Brown [email protected] Government Western Cape Stacy Martin [email protected] Government Overberg District David Beretti [email protected] Municipality Danie Lambrechts [email protected] Cape Agulhas Dean O’ Neill [email protected] Local Municipality Overstrand Local Dennis Hendrik [email protected] Municipality Swellendam Cecil Africa [email protected] Local Municipality Theewaterskloof HSD Wallace [email protected] Local Municipality Lynne Pretorius, Pr.Eng [email protected] ITS Engineers Zaida Tofie [email protected] Wilhelm de Klerk [email protected] iii DOCUMENT CONTROL DATE REPORT STATUS APPROVED BY Authored by: Zaida Tofie SIGNATURE June 2015 1st Draft Approved by: Lynne Pretorius, Pr. Eng SIGNATURE Authored by: Zaida Tofie SIGNATURE March 2016 Final Draft Approved by: Lynne Pretorius, Pr. -

Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast Phase B: Overberg District Municipality

Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast Phase B: Overberg District Municipality Phase 3 Report: Overberg District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Hazard Risk Assessment Final March 2012 REPORT TITLE : Phase 3 Report: Overberg District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Hazard Risk Assessment CLIENT : Provincial Government of the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Strategic Environmental Management PROJECT : Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast. Phase B: Overberg District Municipality AUTHORS : D. Blake : REPORT STATUS Final REPORT NUMBER : 790/3/2/2012 DATE : March 2012 APPROVED BY : S. Imrie D. Blake Project Manager Task Leader This report is to be referred to in bibliographies as: Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning. (2011). Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast. Phase B: Overberg District Municipality. Phase 3 Report: Overberg District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Hazard Risk Assessment. Prepared by Umvoto Africa (Pty) Ltd for the Provincial Government of the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Strategic Environmental Management (March 2012). Phase 3: Overberg DM Sea Level Rise and Flood Hazard Risk Assessment 2012 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Umvoto Africa (Pty) Ltd was appointed by the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning (DEA&DP) to undertake a sea level rise and flood risk assessment for a select disaster prone area along the Western Cape coast. -

Cape Town and Winelands 2020

Koeberg Langerug Nelson’s Breerivier Creek Ou Storkey Wine Valley Adventures: Private NR Kronenburg uniWines Vineyards Nature Reserve Restaurant WORCESTER * Horse Trails * Quad Bike Trails * Wagon Trails * Horse Sales Estate - Nuwehoop * Film & Commercial * Mobile: 083 226 8735 Windmeul Britz Brothers Die Vonds Snake Centre Stofberg Domaine Brahms Cana Estate & Vineyard Wine Estate Under RAWSONVILLE Ridgeback Bernheim Wines Rhebokskloof Oaks Mervida Bird Sanctuary Du Toits Kloof Du Preez Worcester The Rhebok Deetleft Wine Cellar Marcel de Reuke Wines Boland Wine Estate Yacht Club Restaurant Pass Wine Estate Goudini Bistro 44 Cellar PAARL Drakenstein Olive Wines uniWines Vineyards Brandvlei Cape Olive Paarl Diamand Equestrian De Toitskloof - Daschbosch Dam & Guest Farm Molenaars River Wines Paarl Nederburg R101 R302 R304 Mountain Brandvlei R44 Hawequas R27 Local NR Nature Reserve Airlink connects you to Cape Town with direct Mountain R312 Ruitersvlei Wine Estate Klein Huguenot Quaggas Berg flights from Johannesburg, Windhoek, Maun, Parys Catchment Area Private NR Taal Vendome Tunnel Louwshoek Upington, Kimberley, Skukuza, Nelspruit KMIA, Landskroon Wines Monument Voorsorg Road George, Victoria Falls, Hoedspruit, Port Elizabeth De Kelder KWV Wine Emporium Blaauwberg Fairview Wine Laborie and East London. www.flyairlink.com Nature Reserve M58 and Cheese N7 Coleraine M14 Zandwijk De Zoete Inval Drakenstein Holsloot River M48 Meerendal Animal Sanctuary Lion Park R101 Wine Estate & Butterfly World Klapmuts Robben Glen Carlou Wemmershoek Backsberg -

We Believe in Hermanus More About Xplorio

December 2017 WE BELIEVE IN HERMANUS What is this Report? If you’re excited about growing your town’s online presence then this report is going to really make your day. Xplorio Hermanus has been exploding online but don’t just take our word for it, we’ve got phenomenal results for you to browse below. 1 Xpli Hermanu Online Goh We reached 9,672 people searching for information about Hermanus online this month. That's roughly 322 potential customers interested in your town every day. When looking at data from the previous years, we've experienced a 88% growth in users. 2016 January - November 2017 January - November 0 10,000 20,000 30,000 40,000 50,000 60,000 70,000 80,000 2 Xpli Hermanus’ Top Ranking Pile THINGS TO DO ACCOMMODATION BUSINESSES PLACES TO EAT HERMANUS WHALE WATCHERS NORFOLK GUEST HOUSE E-TEC HARBOUR ROCK SEAGRILL HEAVEN & EARTH HEIGHTS VILLA AURA DESIGN GECKO BAR ARTIST CHRISTOPHER REID DOVECOTE COTTAGE HERMANUS TOURISM THE MILKWOOD RESTAURANT SHARK EXPEDITIONS AFRICA HEAVEN & EARTH ACCOMMODATION HERMANUS BUILD IT ROSSI'S ITALIAN RESTAURANT 3 Xpli Hermanus’ Current Goh ACCOMMODATIONS THINGS TO DO CUSTOMERS 836 LEADS 275 CUSTOMERS 1,800 LEADS 594 PLACES TO EAT BUSINESSES CUSTOMERS 140 LEADS 46 CUSTOMERS 3,056 LEADS 1008 * Customers are dened as website visitors with the intent of nding a business. **Leads are customers who enquire via phone or email with a specic business. ***Data provided above are for the last 3 months. ~70% of Hermanus Businesses are already on Xplorio. 1,264 1,800 * Numbers derived from statssa.gov.za 4 Ho doe Xpli promote Hermanus? We publish your town’s content on our social media platforms, driving more trac to Xplorio Hermanus pages and proles.