Carrie Mae Weems' Challenge to the Harvard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Daly, Timothy Michael (2016) Towards a fugitive press: materiality and the printed photograph in artists’ books. Doctoral thesis (PhD), Manchester Metropolitan University. Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/617237/ Usage rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- tive Works 4.0 Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Towards a fugitive press: materiality and the printed photograph in artists’ books Tim Daly PhD 2016 Towards a fugitive press: materiality and the printed photograph in artists’ books Tim Daly A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy MIRIAD Manchester Metropolitan University June 2016 Contents a. Abstract 1 b. Research question 3 c. Field 5 d. Aims and objectives 31 e. Literature review 33 f. Methodology 93 g. Practice 101 h. Further research 207 i. Contribution to knowledge 217 j. Conclusion 220 k. Index of practice conclusions 225 l. References 229 m. Bibliography 244 n. Research outputs 247 o. Appendix - published research 249 Tim Daly Speke (1987) Silver-gelatin prints in folio A. Abstract The aim of my research is to demonstrate how a practice of hand made books based on the materiality of the photographic print and photo-reprography, could engage with notions of touch in the digital age. We take for granted that most artists’ books are made from paper using lithography and bound in the codex form, yet this technology has served neither producer nor reader well. As Hayles (2002:22) observed: We are not generally accustomed to thinking about the book as a material metaphor, but in fact it is an artifact whose physical properties and historical usage structure our interactions with it in ways obvious and subtle. -

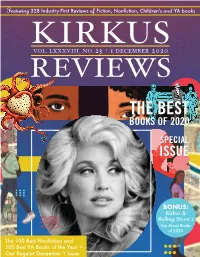

Kirkus Best Books of 2020

Featuring 328 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 23 | 1 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE BONUS: Kirkus & Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020 The 100 Best Nonfiction and 100 Best YA Books of the Year + Our Regular December 1 Issue from the editor’s desk: Books That Deserved More Buzz Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief Every December, I look back on the year past and give a shoutout to those TOM BEER books that deserved more buzz—more reviews, more word-of-mouth [email protected] Vice President of Marketing promotion, more book-club love, more Twitter excitement. It’s a subjec- SARAH KALINA tive assessment—how exactly do you measure buzz? And how much is not [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor enough?—but I relish the exercise because it lets me revisit some titles ERIC LIEBETRAU that merit a second look. [email protected] Fiction Editor Of course, in 2020 every book deserved more buzz. Between the pan- LAURIE MUCHNICK demic and the presidential election, it was hard for many titles, deprived [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor of their traditional publicity campaigns, to get the attention they needed. VICKY SMITH A few lucky titles came out early in the year, disappeared when coronavi- [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor rus turned our world upside down, and then managed to rebound; Douglas LAURA SIMEON [email protected] Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (Grove, Feb. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2016

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2016 Contents Exhibitions 2 Traveling Exhibitions 3 Film Series at the Dryden Theatre 4 Programs & Events 5 Online 7 Education 8 The L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation 8 Photographic Preservation & Collections Management 9 Photography Workshops 10 Loans 11 Objects Loaned for Exhibitions 11 Film Screenings 15 Acquisitions 17 Gifts to the Collections 17 Photography 17 Moving Image 22 Technology 23 George Eastman Legacy 24 Purchases for the Collections 29 Photography 29 Technology 30 Conservation & Preservation 31 Conservation 31 Photography 31 Moving Image 36 Technology 36 George Eastman Legacy 36 Richard & Ronay Menschel Library 36 Preservation 37 Moving Image 37 Financial 38 Treasurer’s Report 38 Fundraising 40 Members 40 Corporate Members 43 Matching Gift Companies 43 Annual Campaign 43 Designated Giving 45 Honor & Memorial Gifts 46 Planned Giving 46 Trustees, Advisors & Staff 47 Board of Trustees 47 George Eastman Museum Staff 48 George Eastman Museum, 900 East Avenue, Rochester, NY 14607 Exhibitions Exhibitions on view in the museum’s galleries during 2016. Alvin Langdon Coburn Sight Reading: ONGOING Curated by Pamela G. Roberts and organized for Photography and the Legible World From the Camera Obscura to the the George Eastman Museum by Lisa Hostetler, Curated by Lisa Hostetler, Curator in Charge, Revolutionary Kodak Curator in Charge, Department of Photography Department of Photography, and Joel Smith, Curated by Todd Gustavson, Curator, Technology Main Galleries Richard L. Menschel -

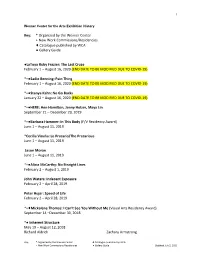

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

ROY Decarava: a RETROSPECTIVE DATES January 25 - May 7, 1996

/ 2. '*-"• The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release December 1995 FACT SHEET EXHIBITION ROY DeCARAVA: A RETROSPECTIVE DATES January 25 - May 7, 1996 ORGANIZATION Peter Galassi, Chief Curator, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art SPONSORSHIP This exhibition and the accompanying publication are supported by a grant from Metropolitan Life Foundation. Additional funding has been provided by Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CONTENT Roy DeCarava (b. 1919) is a leading figure in the lively history of American photography since World War II. Through some 200 black-and-white prints, this major retrospective surveys the artist's achievement, from gentle, intimate pictures of everyday life in Harlem to lyric experiments in poetic metaphor. DeCarava's portraits and jazz photographs -- of Billie Holiday, Milt Jackson, John Coltrane, and many others -- are among the best ever made. Also featured are the series on the moods of darkness and night, the streets and subways of the city, and the civil rights protests of the early 1960s. A lifelong New Yorker, DeCarava in 1952 received the first Guggenheim Fellowship awarded to an African-American photographer. In 1955 his Harlem pictures were published in The Sweet Flypaper of Life, with text by Langston Hughes. Since 1975 he has taught photography at Hunter College, where he is Distinguished Professor of Art of the City University of New York. JAZZ AT MoMA During the run of the exhibition, evenings of "Jazz at MoMA" will feature renowned musicians invited by Roy DeCarava and jazz bassist Ron Carter (Fridays, 5:30 - 7:45 p.m.). -

Annual Report 2009

Bi-Annual 2009 - 2011 REPORT R MUSEUM OF ART UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA CELEBRATING 20 YEARS Director’s Message With the celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Harn Museum of Art in 2010 we had many occasions to reflect on the remarkable growth of the institution in this relatively short period 1 Director’s Message 16 Financials of time. The building expanded in 2005 with the addition of the 18,000 square foot Mary Ann Harn Cofrin Pavilion and has grown once again with the March 2012 opening of the David A. 2 2009 - 2010 Highlighted Acquisitions 18 Support Cofrin Asian Art Wing. The staff has grown from 25 in 1990 to more than 50, of whom 35 are full time. In 2010, the total number of visitors to the museum reached more than one million. 4 2010 - 2011 Highlighted Acquisitions 30 2009 - 2010 Acquisitions Programs for university audiences and the wider community have expanded dramatically, including an internship program, which is a national model and the ever-popular Museum 6 Exhibitions and Corresponding Programs 48 2010 - 2011 Acquisitions Nights program that brings thousands of students and other visitors to the museum each year. Contents 12 Additional Programs 75 People at the Harn Of particular note, the size of the collections doubled from around 3,000 when the museum opened in 1990 to over 7,300 objects by 2010. The years covered by this report saw a burst 14 UF Partnerships of activity in donations and purchases of works of art in all of the museum’s core collecting areas—African, Asian, modern and contemporary art and photography. -

Modern American Grotesque

Modern American Grotesque Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 1 7/31/2009 11:14:21 AM Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 2 7/31/2009 11:14:26 AM Modern American Grotesque LITERATURE AND PHOTOGRAPHY James Goodwin THEOHI O S T A T EUNIVER S I T YPRE ss / C O L U MB us Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 3 7/31/2009 11:14:27 AM Copyright © 2009 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Goodwin, James, 1945– Modern American grotesque : Literature and photography / James Goodwin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13 : 978-0-8142-1108-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10 : 0-8142-1108-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13 : 978-0-8142-9205-1 (cd-rom) 1. American fiction—20th century—Histroy and criticism. 2. Grotesque in lit- erature. 3. Grotesque in art. 4. Photography—United States—20th century. I. Title. PS374.G78G66 2009 813.009'1—dc22 2009004573 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1108-3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9205-1) Cover design by Dan O’Dair Text design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe Typeset in Adobe Palatino Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 4 7/31/2009 11:14:28 AM For my children Christopher and Kathleen, who already possess a fine sense of irony and for whom I wish in time stoic wisdom as well Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 5 7/31/2009 -

TPG Exhibition List

Exhibition History 1971 - present The following list is a record of exhibitions held at The Photographers' Gallery, London since its opening in January 1971. Exhibitions and a selection of other activities and events organised by the Print Sales, the Education Department and the Digital Programme (including the Media Wall) are listed. Please note: The archive collection is continually being catalogued and new material is discovered. This list will be updated intermittently to reflect this. It is for this reason that some exhibitions have more detail than others. Exhibitions listed as archival may contain uncredited worKs and artists. With this in mind, please be aware of the following when using the list for research purposes: – Foyer exhibitions were usually mounted last minute, and therefore there are no complete records of these brief exhibitions, where records exist they have been included in this list – The Bookstall Gallery was a small space in the bookshop, it went on to become the Print Room, and is also listed as Print Room Sales – VideoSpin was a brief series of worKs by video artists exhibited in the bookshop beginning in December 1999 – Gaps in exhibitions coincide with building and development worKs – Where beginning and end dates are the same, the exact dates have yet to be confirmed as the information is not currently available For complete accuracy, information should be verified against primary source documents in the Archive at the Photographers' Gallery. For more information, please contact the Archive at [email protected] -

Photography and African American Education, 1957–1972

“A Matter of Building Bridges”: Photography and African American Education, 1957–1972 Connie H. Choi Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Connie H. Choi All rights reserved ABSTRACT “A Matter of Building Bridges”: Photography and African American Education, 1957–1972 Connie H. Choi This dissertation examines the use of photography in civil rights educational efforts from 1957 to 1972. Photography played an important role in the long civil rights movement, resulting in major legal advances and greater public awareness of discriminatory practices against people of color. For most civil rights organizations and many African Americans, education was seen as the single most important factor in breaking down social and political barriers, and efforts toward equal education opportunities dramatically increased following the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. My dissertation therefore investigates photography’s distinct role in documenting the activities of three educational initiatives—the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957, the Mississippi Freedom Schools formed the summer of 1964, and the Black Panther liberation schools established in Oakland, California, in 1969—to reveal the deep and savvy understanding of civil rights and Black Power organizations of the relationship between educational opportunities and political power. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Carrie Mae Weems

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Carrie Mae Weems Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Weems, Carrie Mae, 1953- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Carrie Mae Weems, Dates: September 10, 2014 Bulk Dates: 2014 Physical 6 uncompressed MOV digital video files (2:57:58). Description: Abstract: Visual artist Carrie Mae Weems (1953 - ) was an award-winning folkloric artist represented in public and private collections around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and The Art Institute of Chicago. Weems was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 10, 2014, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2014_175 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Visual artist Carrie Mae Weems was born on April 20, 1953 in Portland, Oregon to Myrlie and Carrie Weems. Weems graduated from the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia with her B.F.A. degree in 1981, and received her M.F.A. degree in photography from the University of California, San Diego in 1984. From 1984 to 1987, she participated in the graduate program in folklore at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1984, Weems completed her first collection of photographs, text, and spoken word entitled, Family Pictures and Stories. Her next photographic series, Ain't Jokin', was completed in 1988. She went on to produce American Icons in 1989, and Colored People and the Kitchen Table Series in 1990. -

1. Carbon Copy: 6/25 – 6/29 1973

The online Adobe Acrobat version of this file does not show sample pages from Coleman’s primary publishing relationships. The complete print version of A. D. Coleman: A Bibliography of His Writings on Photography, Art, and Related Subjects from 1968 to 1995 can be ordered from: Marketing, Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0103, or phone 520-621-7968. Books presented in chronological order 1. Carbon Copy: 6/25 – 6/29 1973. New York: ADCO interviews” with those five notable figures, serves also as Enterprises, 1973. [Paperback: edition of 50, out of print, “a modest model of critical inquiry.”This booklet, printed unpaginated, 50 pages. 17 monochrome (brown). Coleman’s on the occasion of that opening lecture, was made available first artist’s book. A body-scan suite of Haloid Xerox self- by the PRC to the audiences for the subsequent lectures in portrait images, interspersed with journal/collage pages. the series.] Produced at Visual Studies Workshop Press under an 5. Light Readings: A Photography Critic’s Writings, artist’s residency/bookworks grant from the New York l968–1978. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. State Council on the Arts.] [Hardback and paperback: Galaxy Books paperback, 2. Confirmation. Staten Island: ADCO Enterprises, 1975. 1982; second edition (Albuquerque: University of New [Paperback: first edition of 300, out of print; second edition Mexico Press, 1998); xviii + 284 pages; index. 34 b&w. of 1000, 1982; unpaginated, 48 pages. 12 b&w. Coleman’s The first book-length collection of Coleman’s essays, this second artist’s book.