Kirk 04/13/2008 Page I of 80 I COLLECTIVE MEMORY OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tokyo Babylon, Vol. 1 by Clamp Book

Tokyo Babylon, Vol. 1 by Clamp book Ebook Tokyo Babylon, Vol. 1 currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Tokyo Babylon, Vol. 1 please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 160 pages+++Publisher:::: TokyoPop (May 11, 2004)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1591828716+++ISBN-13:::: 978- 1591828716+++Product Dimensions::::5 x 0.5 x 7.5 inches++++++ ISBN10 1591828716 ISBN13 978-1591828 Download here >> Description: Subaru is the 13th head of the Sumeragi clan, and together with his twin sister Hokuto and the mysterious veterinarian Seishirou, they risk life and limb as they hunt down the ghosts that threaten to destroy the city. A tale of good and evil, light and darkness, innocence and corruption, Tokyo Babylon is a powerful drama.Subaru Sumeragi is a deeply compassionate sixteen year old medium/exorcist who uses his gift to aid lost spirits and the possessed. After a hard day or nights work, he comes home to his devoted, vivacious twin sister Hokuto, whose favorite hobby seems to be trying to hook Subaru up with their friend Seishirou - a veterinarian nine years their senior - in spite of reservations due to the fact that he belongs to a family with a reputation of being in the assassination business that they both choose to ignore.The interaction between the three reaches its climax in the final volume, with hints throughout the series about how things might ultimately turn out, but Subarus interaction with the people he tries to help is interesting in itself. The series handles such topics as gang rape, child abuse, treatment of the elderly, and the ethics of organ transplantation - pretty heavy subject matter.Subaru himself is a highly unique hero. -

Sakura-Con 2013

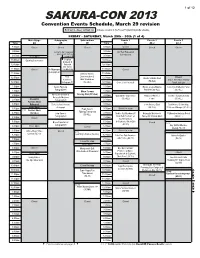

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

Free Companions.Xlsx

Free Companion List By AladdinAnon Key Type = There are 4 types Jump Name = Name of Jump Canon = Canon Charcter, typically a gift Folder = Which folder to find the jump OC = Get an OC Character, typically a "create your own" option Companion = What you get Scenario = required to do a scenario to get the companion Source = Copy and ctrl+F to find their location in jump doc Drawback = Taking the companion is optional after the drawback is finished TG Drive Jumps starting with Numbers Folder Companion Type Source 10 Billion Wives Gauntlets 0 - 10 Billion Wives OC 10 Billion Wives Jumps starting with A Folder Companion Type Source A Brother’s Price A-M Family OC Non Drop-ins A Brother’s Price A-M Husband OC Non Drop-in Women A Brother’s Price A-M Mentor OC Non Drop-in Men A Brother’s Price A-M Aged Spinsters OC Drop-ins of any Gender A Practical Guide to Evil A-M Rival Drawback Rival (+100) A Super Mario…Thing Images 1 OC OC Multiplayer Option After War Gundam X Gundum Frost brothers Drawback A Frosty Reception (+200cp/+300cp) Age of Empires III: Part 1: Blood Age of Empires III Pick 1 of 5 Canon Faction Alignment Ah! My Goddess A-M Goddess Waifu Scenario Child of Ash and Elm Ah! My Goddess A-M Raising Iðavöllr Scenario Iðavöllr AKB49 - Renai Kinshi Jourei (The Rules Against Love) A-M 1 A New Talent OC Drop-In, Fan, Stagework AKB49 - Renai Kinshi Jourei (The Rules Against Love) A-M 1 Canon Companion Canon Kenkyusei, Idol, Producer AKB49 - Renai Kinshi Jourei (The Rules Against Love) A-M Rival Drawback 0CP Rivals AKB49 - Renai Kinshi Jourei (The Rules Against Love) A-M Yoshinaga Drawback 400CP For Her Dreams Aladdin Disney Iago Canon Iago Aladdin Disney Mirage Scenario Mirage’s Wrath Aladdin Disney Forty Thieves Scenario Jumper And The Forty Thieves. -

Reviewed Books

REVIEWED BOOKS - Inmate Property 6/27/2019 Disclaimer: Publications may be reviewed in accordance with DOC Administrative Code 309.04 Inmate Mail and DOC 309.05 Publications. The list may not include all books due to the volume of publications received. To quickly find a title press the "F" key along with the CTRL and type in a key phrase from the title, click FIND NEXT. TITLE AUTHOR APPROVEDENY REVIEWED EXPLANATION DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.2 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.3 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. Workbook of Magic Donald Tyson X 1/11/2018 SR per Mike Saunders 100 Deadly Skills Survivor Edition Clint Emerson X 5/29/2018 DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey X 4/6/2017 WCI DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b. b Teaches fighting techniques along with general fitness DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Is inconsistent with or poses a threat to the safety, 100 Things You’re Not Supposed to Know Russ Kick X 11/10/2017 WCI treatment or rehabilitative goals of an inmate. 100 Ways to Win a Ten Spot Paul Zenon X 10/21/2016 WRC DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 Years of Lynchings Ralph Ginzburg X reviewed by agency trainers, deemed historical Brad Graham and 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genuis Kathy McGowan X 12/23/10 WSPF 309.05(2)(B)2 309.04(4)c.8.d. -

Customer Order Form

#355 | APR18 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE APR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Apr18 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:51:03 PM You'll for PREVIEWS!PREVIEWS! STARTING THIS MONTH Toys & Merchandise sections start with the Back Cover! Page M-1 Dynamite Entertainment added to our Premier Comics! Page 251 BOOM! Studios added to our Premier Comics! Page 279 New Manga section! Page 471 Updated Look & Design! Apr18 Previews Flip Ad.indd 1 3/8/2018 9:55:59 AM BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SWORD SLAYER SEASON 12: DAUGHTER #1 THE RECKONING #1 DARK HORSE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS THE MAN OF JUSTICE LEAGUE #1 THE LEAGUE OF STEEL #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT EXTRAORDINARY DC ENTERTAINMENT GENTLEMEN: THE TEMPEST #1 IDW ENTERTAINMENT THE MAGIC ORDER #1 IMAGE COMICS THE WEATHERMAN #1 IMAGE COMICS CHARLIE’S ANT-MAN & ANGELS #1 BY NIGHT #1 THE WASP #1 DYNAMITE BOOM! STUDIOS MARVEL COMICS ENTERTAINMENT Apr18 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:39:16 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT InSexts Year One HC l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Lost City Explorers #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Carson of Venus: Fear on Four Worlds #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Archie’s Super Teens vs. Crusaders #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Solo: A Star Wars Story: The Official Guide HC l DK PUBLISHING CO The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide Volume 48 SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Mae Volume 1 TP l LION FORGE 1 A Tale of a Thousand and One Nights: Hasib & The Queen of Serpents HC l NBM Shadow Roads #1 l ONI PRESS INC. -

Th Môc Quèc Gia Th¸Ng 7 N¨M 2020 Th

Th môc quèc gia th¸ng 7 n¨m 2020 th«ng tin vµ t¸c phÈm tæng qu¸t 1. B¸ch khoa th : Cho trÎ tõ 3 ®Õn 6 tuæi / Ng« H÷u Long dÞch. - H. : Kim §ång, 2020. - 160tr. : h×nh vÏ ; 23cm. - 190000®. - 2000b s458743 2. B¸ch khoa tri thøc cho trÎ em : Kh¸m ph¸ vµ s¸ng t¹o / Deborah Chancellor, Deborah Murrell, Philip Steele, Barbara Taylor ; NguyÔn ThÞ Nga dÞch. - T¸i b¶n. - H. : D©n trÝ, 2020. - 320tr. : tranh mµu ; 27cm. - 310000®. - 2000b Tªn s¸ch tiÕng Anh: Everything you need to know s458056 3. Biªn tËp viªn h¹ng II : Tµi liÖu båi dìng chøc danh nghÒ nghiÖp / B.s.: D¬ng Xu©n S¬n, NguyÔn Thµnh Lîi, §inh ThÞ Thuý H»ng... ; §inh §øc ThiÖn ch.b. - H. : Th«ng tin vµ TruyÒn th«ng, 2019. - 750tr. : b¶ng ; 24cm. - 240000®. - 1000b §TTS ghi: Bé Th«ng tin vµ TruyÒn th«ng. Trêng §µo t¹o, Båi dìng c¸n bé qu¶n lý Th«ng tin vµ TruyÒn th«ng. - Th môc cuèi mçi chuyªn ®Ò s459809 4. Boucher, Francoize. BÝ kÝp khiÕn b¹n thÝch ®äc s¸ch : Ngay c¶ víi nh÷ng b¹n kh«ng thÝch s¸ch! : Dµnh cho trÎ con vµ ngêi lín / Lêi, minh ho¹: Francoize Boucher ; L¹i ThÞ Thu HiÒn dÞch. - T¸i b¶n lÇn thø 4. - H. : Kim §ång, 2020. - 110tr. : tranh vÏ ; 21cm. - 60000®. - 2000b Tªn s¸ch tiÕng Ph¸p: Le livre qui fait aimer les livres mªme µ ceux qui n'aiment pas lire! s458866 5. -

Contemporary Popular Beliefs in Japan

Hugvísindasvið Contemporary popular beliefs in Japan Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Lára Ósk Hafbergsdóttir September 2010 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindadeild Japanskt mál og menning Contemporary popular beliefs in Japan Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Lára Ósk Hafbergsdóttir Kt.: 130784-3219 Leiðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2010 Abstract This thesis discusses contemporary popular beliefs in Japan. It asks the questions what superstitions are generally known to Japanese people and if they have any affects on their behavior and daily lives. The thesis is divided into four main chapters. The introduction examines what is normally considered to be superstitious beliefs as well as Japanese superstition in general. The second chapter handles the methodology of the survey written and distributed by the author. Third chapter is on the background research and analysis which is divided into smaller chapters each covering different categories of superstitions that can be found in Japan. Superstitions related to childhood, death and funerals, lucky charms like omamori and maneki neko and various lucky days and years especially yakudoshi and hinoeuma are closely examined. The fourth and last chapter contains the conclusion and discussion which covers briefly the results of the survey and what other things might be of interest to investigate further. Table of contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 What is superstition? ............................................................................................... -

Sacred Onsen Resort Bessho Onsen Magazine Sacred Place “Bessho”

BESSTORY SACRED ONSEN RESORT BESSHO ONSEN MAGAZINE SACRED PLACE “BESSHO” A sacred site of sun and earth The name ‘Bessho’ was what first caught my attention. looked for the glut of tourist shops, but instead found TIt has an unusual ring to it, rhythmic but sturdy, and it tempting arrays of local produce. I looked for the has an unusual meaning too. ‘A place apart’. A place kitschy souvenir food items, but saw only old ladies that is different, other, separate. chatting. I strolled through a seemingly endless Getting to this place apart wasn’t the trek I had collection of gently sloping streets, and from a small expected. All it involved was sitting for an hour and a bridge I gazed at the classic Japanese buildings and half amongst snoring businessmen on the Shinkansen the snow-brushed mountains that encircle the town. It from Tokyo to Ueda. The separate place of Bessho has was one of no less than 14 bridges that crisscross its own separate line: the aptly named Bessho Line, Bessho Onsen, and here there was no need to navigate which departs approximately every half hour from around couples posing for selfies. There were only Ueda. From the round windows of the train, I could mountains, and that sunset, which maintained its gaze at rice paddies, quiet towns, and the mountains splendour for longer than I expect of sunsets. that creep at the edges of the landscape. Thirty Before arrival, I had planned for three days in a minutes later, I had arrived at Bessho Onsen Station. -

The Japanese Samurai Code: Classic Strategies for Success Kindle

THE JAPANESE SAMURAI CODE: CLASSIC STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Boye Lafayette De Mente | 192 pages | 01 Jun 2005 | Tuttle Publishing | 9780804836524 | English | Boston, United States The Japanese Samurai Code: Classic Strategies for Success PDF Book Patrick Mehr on May 4, pm. The culture and tradition of Japan, so different from that of Europe, never ceases to enchant and intrigue people from the West. Hideyoshi was made daimyo of part of Omi Province now Shiga Prefecture after he helped take the region from the Azai Clan, and in , Nobunaga sent him to Himeji Castle to face the Mori Clan and conquer western Japan. It is an idea taken from Confucianism. Ieyasu was too late to take revenge on Akechi Mitsuhide for his betrayal of Nobunaga—Hideyoshi beat him to it. Son of a common foot soldier in Owari Province now western Aichi Prefecture , he joined the Oda Clan as a foot soldier himself in After Imagawa leader Yoshimoto was killed in a surprise attack by Nobunaga, Ieyasu decided to switch sides and joined the Oda. See our price match guarantee. He built up his capital at Edo now Tokyo in the lands he had won from the Hojo, thus beginning the Edo Period of Japanese history. It emphasised loyalty, modesty, war skills and honour. About this item. Installing Yoshiaki as the new shogun, Nobunaga hoped to use him as a puppet leader. Whether this was out of disrespect for a "beast," as Mitsuhide put it, or cover for an act of mercy remains a matter of debate. While Miyamoto Musashi may be the best-known "samurai" internationally, Oda Nobunaga claims the most respect within Japan. -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

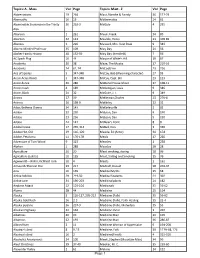

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Protoculture Addicts #61

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PROTOCULTURE ✾ PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................... 4 STAFF WHAT'S GOING ON? ANIME & MANGA NEWS .......................................................................................................... 5 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager VIDEO & MANGA RELEASES ................................................................................................... 6 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor-in-Chief PRODUCTS RELEASES .............................................................................................................. 8 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 10 MODEL NEWS ...................................................................................................................... 47 Contributors Aaron Dawe Kevin Lilliard, James S. Taylor REVIEWS Layout LIVE-ACTION ........................................................................................................................ 15 MODELS .............................................................................................................................. 46 The Safe House MANGA .............................................................................................................................. 54 Cover PA PICKS ............................................................................................................................ -

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun 徳川家康 Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun Constructed and resided at Hamamatsu Castle for 17 years in order to build up his military prowess into his adulthood. Bronze statue of Tokugawa Ieyasu in his youth 1542 (Tenbun 11) Born in Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture (Until age 1) 1547 (Tenbun 16) Got kidnapped on the way taken to Sunpu as a hostage and sold to Oda Nobuhide. (At age 6) 1549 (Tenbun 18) Hirotada, his father, was assassinated. Taken to Sunpu as a hostage of Imagawa Yoshimoto. (At age 8) 1557 (Koji 3) Marries Lady Tsukiyama and changes his name to Motoyasu. (At age 16) 1559 (Eiroku 2) Returns to Okazaki to pay a visit to the family grave. Nobuyasu, his first son, is born. (At age 18) 1560 (Eiroku 3) Oda Nobunaga defeats Imagawa Yoshimoto in Okehazama. (At age 19) 1563 (Eiroku 6) Engagement of Nobuyasu, Ieyasu’s eldest son, with Tokuhime, the daughter of Nobunaga. Changes his name to Ieyasu. Suppresses rebellious groups of peasants and religious believers who opposed the feudal ruling. (At age 22) 1570 (Genki 1) Moves from Okazaki 天龍村to Hamamatsu and defeats the Asakura clan at the Battle of Anegawa. (At age 29) 152 1571 (Genki 2) Shingen invades Enshu and attacks several castles. (At age 30) 豊根村 川根本町 1572 (Genki 3) Defeated at the Battle of Mikatagahara. (At age 31) 東栄町 152 362 Takeda Shingen’s151 Path to the Totoumi Province Invasion The Raid of the Battlefield Saigagake After the fall of the Imagawa, Totoumi Province 犬居城 武田本隊 (別説) Saigagake Stone Monument 山県昌景隊天竜区 became a battlefield between Ieyasu and Takeda of Yamagata Takeda Main 堀之内の城山Force (another theoried the Kai Province.