Invasion and Dispossession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

AUG 2008 Wurundjeri RAP Appointment Decision Pdf 43.32 KB

DECISION OF THE VICTORIAN ABORIGINAL HERITAGE COUNCIL IN RELATION TO AN APPLICATION BY WURUNDJERI TRIBE LAND AND COMPENSATION CULTURAL HERITAGE COUNCIL INC TO BE A REGISTERED ABORIGINAL PARTY DATE OF DECISION: 22 AUGUST 2008 Decision The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (“the Council”) registers the Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc (“Wurundjeri Inc”) as a registered Aboriginal party (“RAP”) over part of its application area. A map showing the area for which Wurundjeri Inc has been made a RAP (“the RAP Area”) is attached (Attachment 1). The Council is still considering the remaining area for which Wurundjeri Inc has sought to be a RAP. Reasons for Decision The Council accepts that Wurundjeri Inc is an organisation that represents the Traditional Owners of the RAP Area. The members of Wurundjeri Inc are all descendants of a Woiwurrung / Wurundjeri man Bebejan, through his daughter Annie Borate (Boorat), and in turn, her son Robert Wandin (Wandoon). Bebejan was Ngurungaeta (headman) of the Wurundjeri people and was present at John Batman’s ‘treaty’ signing in 1835. Wurundjeri Inc was incorporated in 1985 and has had a long history of managing and protecting cultural heritage in its application area on behalf of Woiwurrung people. The Council was satisfied Wurundjeri Inc is capable of carrying out the functions of a RAP. RAP applications have also been made by other Traditional Owner groups in the vicinity of (and in some cases overlapping with) the Wurundjeri RAP application area. These include the Wathaurung/ Wathaurong people to the west, the Dja Dja Wurrung/ Jaara Jaara people to the north-west, the Taungurung people to the north, the Gunai/Kurnai people to the east and the Boon Wurrung/ Bunurong people to the south. -

Fighting Extinction Challenge Teacher Answers Middle Years 9-10

Fighting Extinction Challenge Teacher Answers Middle Years 9-10 Wurundjeri Investigation We are all custodians of the land, just as the Wurundjeri have been for thousands of years. During your independent investigation around the Sanctuary look for ways that the Wurundjeri people lived on country and record these observations in the box below. Look (what you saw) Hear (what you heard) I wonder… (questions to ask an expert or investigate back at school ) Bunjil Soundscapes Waa Information from education Mindi officers Signs about plant uses Dreaming stories at feature shows Signs about animal dreaming Information about Wurundjeri stories Seasons Sculptures Didjeridoo Scar Tree Bark Canoe Gunyah Information about Coranderrk William Barak sculpture Information about William Barak Artefacts (eg eel trap, marngrook, possum skin cloak) 1. Identify and explain how did indigenous people impact upon their environment? Indigenous people changed the landscape using fire stick farming which also assisted hunting Aboriginal people used their knowledge of the seasons to optimise hunting, gathering, eel farming and more Aboriginal people used organic local materials to create tools to assist them with hunting and gathering their food i.e. eel traps, woven grass baskets, rock fish traps etc. They only ever took what they needed from the land and had a deep respect and spiritual connection to the land and their surroundings. 2. How are humans impacting on natural resources in today’s society? How does this affect wildlife? When the land is disrespected, damaged or destroyed, this can have real impact on the wellbeing of people, plants and animals. European settlers and modern day humans have caused land degradation by: •Introducing poor farming practices causing land degradation •Introducing noxious weeds •Changing water flow courses and draining wetlands •Introducing feral animals •Destroying habitat through urbanization, logging and farming practices 3. -

Melbourne-Dreaming-Intro 1.Pdf (Pdf, 1.91

ABOUT THIS BOOK Melbourne Dreaming is both a guide book and social history of Melbourne, and the events and cultural traditions that have shaped local Aboriginal people’s lives. It aims to show where to look to gain a better understanding of the rich heritage and complex culture of Aboriginal people in Melbourne both before and since colonisation. It was first published in 1997. This is a completely updated and expanded edition. Melbourne Dreaming provides practical information on visiting both historical and contemporary sites located in the city centre, surrounding suburbs and outer areas. Arranged into seven precincts, Melbourne Dreaming takes you to beaches, parklands, camping places, historical sites, exhibitions, cultural displays and buildings. For Melbourne’s Aboriginal people the landscape prior to European settlement over which we travel was the face of the divine — the imprint of the ancestral creation beings that shaped the landscape on their epic journeys. Exploring Melbourne’s Aboriginal places is a way of paying respect to this sacred tradition while learning more about our shared and ancient history. Sites include locations and traces of important places before European settlement in 1835 such as shell middens, scarred trees, wells, fish traps, mounds and quarries. Other sites describe critical events that occurred because of the impact of European settlement. More recent places are the focus of contemporary life. What these places share in common is that each illustrates an important part of the overall story of the first inhabitants, the Kulin. Stories and photographs of some places of interest which have restricted access or cannot be visited have also been included. -

The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story Jessica K Weir

The legal outcomes the Gunditjmara achieved in the 1980s are often overlooked in the history of land rights and native title in Australia. The High Court Onus v Alcoa case and the subsequent settlement negotiated with the State of Victoria, sit alongside other well known bench marks in our land rights history, including the Gurindji strike (also known as the Wave Hill Walk-Off) and land claim that led to the development of land rights legislation in the Northern Territory. This publication links the experiences in the 1980s with the Gunditjmara’s present day recognition of native title, and considers the possibilities and limitations of native title within the broader context of land justice. The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story JESSICA K WEIR Euphemia Day, Johnny Lovett and Amy Williams filming at Cape Jessica Weir together at the native title Bridgewater consent determination Amy Williams is an aspiring young Jessica Weir is a human geographer Indigenous film maker and the focused on ecological and social communications officer for the issues in Australia, particularly water, NTRU. Amy has recently graduated country and ecological life. Jessica with her Advanced Diploma of completed this project as part of her Media Production, and is developing Research Fellowship in the Native Title and maintaining communication Research Unit (NTRU) at the Australian strategies for the NTRU. Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story JESSICA K WEIR First published in 2009 by the Native Title Research Unit, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies GPO Box 553 Canberra ACT 2601 Tel: (61 2) 6246 1111 Fax: (61 2) 6249 7714 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au/ Written by Jessica K Weir Copyright © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. -

Top 10 Aboriginal Children's Books for Victoria

the importance of understanding where we with her dingos, looking for grubs and berries. come from and how to relate to the land and She walked for a long time dragging a digging Top 10 Aboriginal children’s water surrounding us all. Woiwurrung words, stick behind her, which made a track along the such as ‘wominjeka’, are introduced through the ground. The sound of the stick woke the snake, VWRU\DQGZHDUHRʏHUHGDQLQVLJKWLQWRKRZ and he became very angry and thrashed to and books for Victoria Aboriginal communities relate to one another fro, causing the track to get bigger. Soon after, through acknowledging territorial boundaries, it rained and this was how the Murray River was seeking permission to enter other lands and made. This is an engaging and interesting way performing Welcomes to Country. A video of for educators and teachers to introduce the Here are our top 10 children’s books written by Aunty Joy reading her book can be viewed at: topic of belief systems. Victorian Aboriginal people who feel a sense of http://bit.ly/WelcomeToCountryBook 8. Respect 5. Took the belonging to their nations, clans, land and culture. $XQW\)D\H0XLU6XH/DZVRQ Children Away /LVD.HQQHG\ LOOXVWUDWRU Archie Roach / Ruby Hunter Aunty Fay is a Boon Wurrung (illustrator) with paintings by and Wamba Wamba Elder MATILDA DARVALL, Senior Policy Officer & Peter Hudson MERLE HALL, Koorie Inclusion Consultant, ZKRZURWHWKLVERRNZLWK6XH/DZVRQDQ Victorian Aboriginal Education Association Took the Children Away is a story written award-winning children’s author. This book Incorporated (VAEAI) by well-known singer Archie Roach, and teaches us how to respect our Elders, our illustrated by his late partner Ruby Hunter. -

Crib Point Pakenham Pipeline Aboriginal Cultural Heritage

Crib Point Pakenham Pipeline Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Desktop Assessment Client: APA Transmission Pty Limited (ABN 84 603 054 404) Author: Anita Barker 15 August 2018 Crib Point Pakenham Pipeline Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Desktop Assessment Client: APA Transmission Pty Limited (ABN 84 603 054 404) Author: Anita Barker Date: 15 August 2018 Front Cover: VAHR 7921-0036 from Denham Road, Tyabb (View SSW) Contents 1. Introduction & Project Overview ................................................................................. 1 1.1. Purpose of the Report ............................................................................................. 1 1.2. The Activity Area ..................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Limitations .............................................................................................................. 2 2. Legislation .................................................................................................................... 4 2.1. EPBC Act 1999 ....................................................................................................... 4 2.2. The Planning & Environment Act 1987 .................................................................... 4 2.3. Environment Effects Act 1978 ................................................................................. 5 2.4. Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 .................................................................................. 6 3. Methodology ............................................................................................................... -

Engaging Indigenous Communities

Engaging Indigenous Communities REGIONAL INDIGENOUS FACILITATOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLE’S GOALS AND The Port Phillip & Westernport CMA employs a Regional ASPIRATIONS Indigenous Facilitator funded through the Australian During 2014/15, a study was undertaken with Government’s National Landcare Programme. In Wurundjeri, Wathaurung, Wathaurong and Boon 2014/15, the facilitator arranged numerous events Wurrung people regarding their communities’ goals and and activities to improve the Indigenous cultural aspirations for involvement in land management and awareness and understanding of Board members and sustainable agriculture. The study improved the mutual staff from the Port Phillip & Westernport CMA and from understanding of priority activities for the future and various other organisations and community groups. set a basis for potential formal agreements between The facilitator also worked directly with Indigenous the Port Phillip & Westernport CMA and the Indigenous organisations and communities to document their goals organisations. relating to natural resource management and agriculture. A coordinated program of grants was established to help INDIGENOUS ENVIRONMENT GRANTS Indigenous organisations undertake on-ground projects and training to increase employment opportunities. In 2014/15, $75,000 of Indigenous environment grants were awarded as part of the Port Phillip & Westernport IMPROVING CULTURAL AWARENESS AND CMA’s project. This included grants to: UNDERSTANDING • Wathaurung Aboriginal Corporation to run 4 community, business and corporate -

From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 19 Access to Justice: The Social Responsibility of Lawyers | Contemporary and Comparative Perspectives on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples January 2005 From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia Lisa Strelein Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Lisa Strelein, From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia, 19 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 225 (2005), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol19/iss1/14 This Rights of Indigenous Peoples - Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia Dr. Lisa Strelein* INTRODUCTION In more than a decade since Mabo v. Queensland II’s1 recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights to their traditional lands, the jurisprudence of native title has undergone significant development. The High Court of Australia decisions in Ward2 and Yorta Yorta3 in 2002 sought to clarify the nature of native title and its place within Australian property law, and within the legal system more generally. Since these decisions, lower courts have had time to apply them to native title issues across the country. This Article briefly examines the history of the doctrine of discovery in Australia as a background to the delayed recognition of Indigenous rights in lands and resources. -

3 Researchers and Coranderrk

3 Researchers and Coranderrk Coranderrk was an important focus of research for anthropologists, archaeologists, naturalists, historians and others with an interest in Australian Aboriginal people. Lydon (2005: 170) describes researchers treating Coranderrk as ‘a kind of ethno- logical archive’. Cawte (1986: 36) has argued that there was a strand of colonial thought – which may be characterised as imperialist, self-congratulatory, and social Darwinist – that regarded Australia as an ‘evolutionary museum in which the primi- tive and civilised races could be studied side by side – at least while the remnants of the former survived’. This chapter considers contributions from six researchers – E.H. Giglioli, H.N. Moseley, C.J.D. Charnay, Rev. J. Mathew, L.W.G. Büchner, and Professor F.R. von Luschan – and a 1921 comment from a primary school teacher, named J.M. Provan, who was concerned about the impact the proposed closure of Coranderrk would have on the ability to conduct research into Aboriginal people. Ethel Shaw (1949: 29–30) has discussed the interaction of Aboriginal residents and researchers, explaining the need for a nuanced understanding of the research setting: The Aborigine does not tell everything; he has learnt to keep silent on some aspects of his life. There is not a tribe in Australia which does not know about the whites and their ideas on certain subjects. News passes quickly from one tribe to another, and they are quick to mislead the inquirer if it suits their purpose. Mr. Howitt, Mr. Matthews, and others, who made a study of the Aborigines, often visited Coranderrk, and were given much assistance by Mr. -

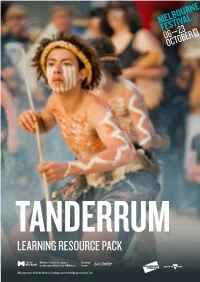

Learning Resource Pack

TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK Melbourne Festival’s free program Presenting proudly supported by the City of Melbourne Partner With support from VicHealth, Newsboys Foundation and the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK INTRODUCTION STATEMENT FROM ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY Welcome to the study guide of the 2016 Melbourne Festival production of ILBIJERRI (pronounced ‘il BIDGE er ree’) is a Woiwurrung word meaning Tanderrum. The activities included are related to the AusVELS domains ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. as outlined below. These activities are sequential and teachers are ILBIJERRI is Australia’s leading and longest running Aboriginal and encouraged to modify them to suit their own curriculum planning and Torres Strait Islander Theatre Company. the level of their students. Lesson suggestions for teachers are given We create challenging and inspiring theatre creatively controlled by within each activity and teachers are encouraged to extend and build on Indigenous artists. Our stories are provocative and affecting and give the stimulus provided as they see fit. voice to our unique and diverse cultures. ILBIJERRI tours its work to major cities, regional and remote locations AUSVELS LINKS TO CURRICULUM across Australia, as well as internationally. We have commissioned 35 • Cross Curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander new Indigenous works and performed for more than 250,000 people. History and Cultures We deliver an extensive program of artist development for new and • The Arts: Creating and making, Exploring and responding emerging Indigenous writers, actors, directors and creatives. • Civics and Citizenship: Civic knowledge and Born from community, ILBIJERRI is a spearhead for the Australian understanding, Community engagement Indigenous community in telling the stories of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia today from an Indigenous perspective. -

Racist Structures and Ideologies Regarding Aboriginal People in Contemporary and Historical Australian Society

Master Thesis In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science: Development and Rural Innovation Racist structures and ideologies regarding Aboriginal people in contemporary and historical Australian society Robin Anne Gravemaker Student number: 951226276130 June 2020 Supervisor: Elisabet Rasch Chair group: Sociology of Development and Change Course code: SDC-80436 Wageningen University & Research i Abstract Severe inequalities remain in Australian society between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. This research has examined the role of race and racism in historical Victoria and in the contemporary Australian government, using a structuralist, constructivist framework. It was found that historical approaches to governing Aboriginal people were paternalistic and assimilationist. Institutions like the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines, which terrorised Aboriginal people for over a century, were creating a racist structure fuelled by racist ideologies. Despite continuous activism by Aboriginal people, it took until 1967 for them to get citizens’ rights. That year, Aboriginal affairs were shifted from state jurisdiction to national jurisdiction. Aboriginal people continue to be underrepresented in positions of power and still lack self-determination. The national government of Australia has reproduced historical inequalities since 1967, and racist structures and ideologies remain. ii iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Elisabet Rasch, for her support and constructive criticism. I thank my informants and other friends that I met in Melbourne for talking to me and expanding my mind. Floor, thank you for showing me around in Melbourne and for your never-ending encouragement since then, via phone, postcard or in person. Duane Hamacher helped me tremendously by encouraging me to change the topic of my research and by sharing his own experiences as a researcher.