Abject Femininity in Willie Doherty's Same Difference and Closure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrorism and Political Violence Who Were The

This article was downloaded by: [University College London] On: 28 July 2014, At: 04:40 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Terrorism and Political Violence Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ftpv20 Who Were the Volunteers? The Shifting Sociological and Operational Profile of 1240 Provisional Irish Republican Army Members Paul Gill a & John Horgan b a Department of Security and Crime Science , University College London , London , UK b International Center for the Study of Terrorism, The Pennsylvania State University, State College , Pennsylvania , USA Published online: 14 Jun 2013. To cite this article: Paul Gill & John Horgan (2013) Who Were the Volunteers? The Shifting Sociological and Operational Profile of 1240 Provisional Irish Republican Army Members, Terrorism and Political Violence, 25:3, 435-456, DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2012.664587 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2012.664587 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Versions of published Taylor & Francis and Routledge Open articles and Taylor & Francis and Routledge Open Select articles posted to institutional or subject repositories or any other third-party website are without warranty from Taylor & Francis of any kind, either expressed or implied, including, but not limited to, warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non- infringement. -

LIST of POSTERS Page 1 of 30

LIST OF POSTERS Page 1 of 30 A hot August night’ feauturing Brush Shiels ‘Oh no, not Drumcree again!’ ‘Sinn Féin women demand their place at Irish peace talks’ ‘We will not be kept down easy, we will not be still’ ‘Why won’t you let my daddy come home?’ 100 years of Trade Unionism - what gains for the working class? 100th anniversary of Eleanor Marx in Derry 11th annual hunger strike commemoration 15 festival de cinema 15th anniversary of hunger strike 15th anniversary of the great Long Kesh escape 1690. Educate not celebrate 1969 - Nationalist rights did not exist 1969, RUC help Orange mob rule 1970s Falls Curfew, March and Rally 1980 Hunger Strike anniversary talk 1980 Hunger-Strikers, 1990 political hostages 1981 - 1991, H-block martyrs 1981 H-block hunger-strike 1981 hunger strikes, 1991 political hostages 1995 Green Ink Irish Book Fair 1996 - the Nationalist nightmare continues 20 years of death squads. Disband the murderers 200,000 votes for Sinn Féin is a mandate 21st annual volunteer Tom Smith commemoration 22 years in English jails 25 years - time to go! Ireland - a bright new dawn of hope and peace 25 years too long 25th anniversary of internment dividedsociety.org LIST OF POSTERS Page 2 of 30 25th anniversary of the introduction of British troops 27th anniversary of internment march and rally 5 reasons to ban plastic bullets 5 years for possessing a poster 50th anniversary - Vol. Tom Williams 6 Chontae 6 Counties = Orange state 75th anniversary of Easter Rising 75th anniversary of the first Dáil Éireann A guide to Irish history -

WILLIE DOHERTY B

WILLIE DOHERTY b. 1959, Derry, Northern Ireland Lives and works in Derry EDUCATION 1978-81 BA Hons Degree in Sculpture, Ulster Polytechnic, York Street 1977-78 Foundation Course, Ulster Polytechnic, Jordanstown FORTHCOMING & CURRENT EXHIBITIONS 2020 ENDLESS, Kerlin Gallery, online viewing room, (27 May - 16 June 2020), (solo) SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Remains, Regional Cultural Centre, Letterkenny, Ireland Inquieta, Galeria Moises Perez de Albeniz, Madrid, Spain 2017 Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich, Switzerland Remains, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, South Korea No Return, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA Loose Ends, Matt’s Gallery, London, UK 2016 Passage, Alexander and Bonin, New York Lydney Park Estate, Gloucestershire, presented by Matt’s Gallery + BLACKROCK Loose Ends, Regional Centre, Letterkenny; Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland Home, Villa Merkel, Germany 2015 Again and Again, Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian, CAM, Lisbon Panopticon, Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA), Salt Lake City 2014 The Amnesiac and other recent video and photographic works, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA UNSEEN, Museum De Pont, Tilburg The Amnesiac, Galería Moisés Pérez de Albéniz, Madrid REMAINS, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 2013 UNSEEN, City Factory Gallery, Derry Secretion, Neue Galerie, Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel Secretion, The Annex, IMMA, Dublin Without Trace, Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich 2012 Secretion, Statens Museum for Kunst, National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen LAPSE, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin Photo/text/85/92, Matts Gallery, London One Place Twice, -

Pdf, 144.24 KB

Daniel Jewesbury artist | writer | lecturer | editor | curator Såggatan 65B – 1301, 414 67 Göteborg, Sweden. [email protected] / [email protected] +44 (0)7929 205361 / +46 (0)79 313 6253 danieljewesbury.org Born London, 23rd November, 1972 Education 1997 - 2001 Ph.D (Media Studies), University of Ulster at Coleraine 1992 - 1996 BA (Hons) Fine Art (Sculpture), National College of Art and Design, Dublin (2:1) Employment & other experience 2017 - Universitetslektor, Fri Konst, Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg 2018 - Fri Konst unit representative, Valand ACademy Research Board 2017 - Associate Researcher, Centre for Media Research, Ulster University 2013 - 2017 Lecturer in Film, Ulster University 2016 Curator, Tulca 2016, Festival of Visual Arts, Galway 2015 Co-curator, Periodical Review #5, Pallas ProjeCts, Dublin 2014 Fellow, Zentrum für Kunst und Urbanistik (ZK/U), Centre for Art & Urbanism, Berlin 2008 - 2014 Part-time PhD Supervisor, National College of Art & Design, Dublin (FaCulties of Fine Art / Visual Culture) 2003 - 2014 Co-editor, Variant magazine (www.variant.org.uk) 2010 - 2013 Visiting Fellow, Graduate SChool of Creative Arts & Media (GradCAM), Dublin 2010 - 2011 Chair, Digital Art Studios, Belfast 2010 Curator, re : public, group exhibition and event series, Temple Bar Gallery, Dublin 2009 Lead writer, EC Culture Programme funding bid (suCCessful), The Artist as Citizen, for GradCam, Dublin 2009 Nominee: Paul Hamlyn Award 2008 - 2009 Northern Representative, Visual Artists Ireland 2008 - 2009 Lead national researCher -

The Burning Bush—Online Article Archive

The Burning Bush—Online article archive Republican News which Republicans don't like to read The following are some items of news about Irish republicans and their dark world of crime and evil which did not get the media coverage that they deserved. Fomer IRA man guilty of sex abuse Vincent McKenna, 37, from Haypark Avenue in Belfast was convicted of sexually abusing his daughter Sorcha over a period of eight years, between 1985 and 1993. He was named publicly on Friday after 18-year-old Sorcha waived her right to anonymity. The abuse was said to have happened when the family lived in Monaghan. A jury of seven men and five women found McKenna guilty of the charges after two hours of deliberations, and following a three-day trial at Monaghan Circuit Court. The accused was sentenced to three years in jail. McKenna was a leading spokesman of a campaign for the victims of paramilitary vio- lence for a number of years during the very period he was victimising his own child. McGuinness 'elected by vote-rigging' A former Sinn Fein election organiser has claimed that Martin McGuinness got into politics, thanks to systematic vote-stealing by republicans. Willie Carlin, a key Sinn Fein worker from 1982 to 1985, says a decisive 2,700 votes were cast fraudulently for the present Northern Ireland education minister by party supporters in the 1982 Stormont assembly elections. Later, a party was organised for the election workers and Carlin alleges that a plaque was presented to the person who had voted the most times. -

Lost in Transition? Republican Women's Struggle After Armed

Lost In Transition? Republican Women’s Struggle After Armed Struggle. A thesis submitted by Niall Gilmartin B.A., for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Department, Faculty of Social Science, Maynooth University, Ireland. Date of Submission: March 2015. Head of Department: Prof. Mary Corcoran Research Supervisors: Dr. Theresa O’Keefe. Prof. Honor G. Fagan This research is funded by the Irish Research Council Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. vi Summary ............................................................................................................................... viii Chapter One-Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 Women & Conflict Transition: Contextualising the Study.................................................... 2 Why Republican Women?: The Purpose, Significance & Limitations of the Study ............. 7 Terms and Definitions.......................................................................................................... 12 Organisation of the Chapters ............................................................................................... 16 Chapter Two -‘Does the Body Rule the Mind or the Mind Rule the Body?’: The Perpetual Dilemmas of Men Doing Feminist -

Statewatch Bulletin

Statewatch bulletin Number 4 September/October 1991 POLICING 298 road checks involving 38,700 vehicles were carried out in 1990. There were only 18 arrests connected with the reason for the road check and 33 arrests for reasons not connected with it. Police powers in action In 1990 a total of 542 people were detained by the police for more than 24 hours of whom 465 were released without charge and 77 The only measure of the exercise of police powers under the Police were detained for longer periods. Four hundred and one people and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) in England and Wales is were detained without charge under warrant for more than 36 the annual Home Office statistics. The statistics cover stop and hours; of these 324 were eventually charged. searches, road-blocks, extended detention and intimate body Intimate body searches involving the examination of body orifices searches. such as the anus or vagina were carried out on 51 people in The publication of figures for 1990 in July confirms another leap custody. In only 4 cases was the suspected item found. in the `stop and search' figures - from 202,800 to 256,900 -and Twenty-nine of the 43 police forces covered carried out no another drop in the percentage subsequently arrested - from 17% in intimate body searches; 22 of the 51 searches were carried out in 1986 to 16% in 1989 and to 15% in 1990. London. These stop and searches were made by the police on the grounds Statistics on the operation of certain police powers under the of suspected stolen property, drugs, firearms, offensive weapons Police and Criminal Evidence Act, England and Wales, 1984, and other offences. -

Art As Direct Political Action:” an Investigation Through Case Studies and Interviews

“ART AS DIRECT POLITICAL ACTION:” AN INVESTIGATION THROUGH CASE STUDIES AND INTERVIEWS SUBMITTED BY EMILY MEINHARDT CLAREMONT MCKENNA COLLEGE SIT IRELAND, FALL 2008 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF ROISIN KENNEDY, PHD ART HISTORY, UCD Art as Direct Political Action Emily Meinhardt 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………3 II. Methodology……………………………………………………………..........4 III. Main Body a. Part One: Case Studies i. Setting the Stage for Irish Contemporary Art…………..…………9 ii. Case Study: Robert Ballagh………………..……………….……10 iii. Case Study: Willie Doherty………………………………..…….14 iv. Ballagh and Doherty Case Studies in Contrast………...………...17 b. Part Two: Key Questions i. Art and Politics Re-examined……………………………...……20 ii. National Identity…………………………………………………21 iii. Public Money Complicating Political Art………………….…….24 iv. Is Irish Art Different?.....................................................................26 IV. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………...27 V. Bibliography………………………………………...……………………….30 VI. Appendix a. Images……………………………………………………………………33 b. Interviews i. Sean Kissane……………………………………………………..36 ii. Robert Ballagh………………………………………...…………40 iii. Dominic Bryan…………………………………...………………42 iv. Peter Richards……………………………………………………45 v. Theo Sims………………………………………………..………48 vi. Pauline Ross………………………………………………...……50 vii. Sighle Bhreathnach-Lynch…………………………………….…50 viii. Declan McGonagle………………………………………………52 Art as Direct Political Action Emily Meinhardt 3 ONE: INTRODUCTION In 1970, Artforum, an international magazine of contemporary art, conducted -

The Catalogues of the Orchard Gallery: a Contribution to Critical and Historical Discourses in Northern Ireland, 1978-2003

The catalogues of the Orchard Gallery: a contribution to critical and historical discourses in Northern Ireland, 1978-2003 Gabriel N. Gee The Orchard Gallery opened in Derry in 1978. It was set up by Derry City Council, which appointed a then young artist and art teacher, Declan McGonagle, as its first exhibition director. The second largest city of Northern Ireland did not have any artistic infrastructure at the time, and the Orchard was launched as an attempt to make up for this absence. From the outset, the artistic programme of the gallery aimed to exhibit a range of practitioners, both emerging and established, and coming from diverse geographical horizons, who were asked to produce works specifically for the gallery. The work had to respond to ‘the gallery’s ethos, which was about the place, and the interaction and the relationship between the artist who comes from outside and the place’.1 Derry, or Londonderry, is a city of circa 80 000 people located on the northern confines of the Irish and British isles, on the border between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. Its history has long been rooted in a dual narrative. An early Celtic settlement brought the first naming of the site, Doire Calgach, or Calgach Oak Wood.2 With the expansion of the English rule in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the city was renamed Londonderry, an affirmation of the ties that now closely connected it to Britain. When the Orchard opened to the public, the city was at the heart of a conflict that since the 1960s had opposed in Northern Ireland with increasingly violent manifestations the Republican and Loyalist communities. -

Statewatch Bulletin

Statewatch bulletin Vol 5 no 2, March-April 1995 EUROPE make the new consortia aware of their duties. The government will also have to create new regulations for international cooperation so EU that the necessary surveillance will be able to operate." “Legally permitted surveillance” Another "problem" for surveillance under the new systems is that The Police Cooperation Working Group, which comes under the satellites will communicate with earth-bound stations which will K4 Committee, has been presented with a plan for the next function as distribution points for a number of adjoining countries - generation of satellite-based telecommunications systems - planned there will not be a distribution point in every country. While the to come into operation in 1998. It would: existing "methods of legally permitted surveillance of immobile and mobile telecommunications have hitherto depended on national “tag” each individual subscriber in view of a possibly necessary infrastructures" (italics added) the: surveillance activity. "providers of these new systems do not come under the legal The report, drawn up for the Working Group by the UK delegation, guidelines used hitherto for a legal surveillance of says that the new mobile individual communications working telecommunications." through satellites are already underway and unlike the current earth-bound systems based on GSM-technology will ”in many The report says it would be difficult to monitor the "upward and cases operate from outside the national territory". downward connections to the distribution point" so the "tag" would This is the latest in a number of initiatives concerning policing, start the surveillance at "the first earthbound distribution point". -

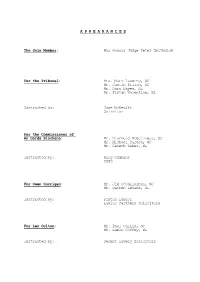

APPEARANCES the Sole Member: His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick

A P P E A R A N C E S The Sole Member: His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick For the Tribunal: Mrs. Mary Laverty, SC Mr. Justin Dillon, SC Mr. Dara Hayes, BL Mr. Fintan Valentine, BL Instructed by: Jane McKevitt Solicitor For the Commissioner of An Garda Siochana: Mr. Diarmuid McGuinness, SC Mr. Michael Durack, SC Mr. Gareth Baker, BL Instructed by: Mary Cummins CSSO For Owen Corrigan: Mr. Jim O'Callaghan, SC Mr. Darren Lehane, BL Instructed by: Fintan Lawlor Lawlor Partners Solicitors For Leo Colton: Mr. Paul Callan, SC Mr. Eamon Coffey, BL Instructed by: Dermot Lavery Solicitors For Finbarr Hickey: Fionnuala O'Sullivan, BL Instructed by: James MacGuill & Co. For the Attorney General: Ms. Nuala Butler, SC Mr. Douglas Clarke, SC Instructed by: CSSO For Freddie Scappaticci: Niall Mooney, BL Pauline O'Hare Instructed by: Michael Flanigan Solicitor For Kevin Fulton: Mr. Neil Rafferty, QC Instructed by: John McAtamney Solicitor For Breen Family: Mr. John McBurney For Buchanan Family/ Heather Currie: Ernie Waterworth McCartan Turkington Breen Solicitors NOTICE: A WORD INDEX IS PROVIDED AT THE BACK OF THIS TRANSCRIPT. THIS IS A USEFUL INDEXING SYSTEM, WHICH ALLOWS YOU TO QUICKLY SEE THE WORDS USED IN THE TRANSCRIPT, WHERE THEY OCCUR AND HOW OFTEN. EXAMPLE: - DOYLE [2] 30:28 45:17 THE WORD “DOYLE” OCCURS TWICE PAGE 30, LINE 28 PAGE 45, LINE 17 I N D E X Witness Page No. Line No. KEVIN FULTON CROSS-EXAMINED BY MR. DURACK 1 10 CROSS-EXAMINED BY MR. O'ROURKE 34 2 CROSS-EXAMINED BY MS. MULVENNA 76 18 EXAMINED BY MR. -

In Northern Ireland: the Irish Linen Memorial 2001-2005 Lycia Danielle Trouton University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2005 An intimate monument (re)-narrating 'the troubles' in Northern Ireland: the Irish Linen Memorial 2001-2005 Lycia Danielle Trouton University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Trouton, Lycia D, An intimate monument (re)-narrating 'the troubles' in Northern Ireland: the Irish Linen Memorial 2001-2005, DCA thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/779 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] An Intimate Monument An Intimate Monument (re)‐narrating ‘the troubles’ in Northern Ireland: The Irish Linen Memorial 2001 – 2005 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Creative Arts University of Wollongong Lycia Danielle Trouton 1991 Master of Fine Arts (Sculpture), Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, USA 1988 Bachelor of Fine Arts (Hons) (Sculpture), Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA 1997 Licentiate Teacher’s Diploma (Speech and Drama) Trinity College London 1985 Associate Teacher’s Diploma (Speech and Drama) Trinity College London The Faculty of Creative Arts 2005 ii Certification I, Lycia Danielle Trouton, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Creative Arts, in the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Lycia Danielle Trouton Date ________________ iii Figure 1: Australian Indigenous artist Yvonne Koolmatrie (left) with Diana Wood Conroy, 2002 Adelaide Festival of the Arts, South Australia.