Shane Alcobia-Murphy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WILLIE DOHERTY B

WILLIE DOHERTY b. 1959, Derry, Northern Ireland Lives and works in Derry EDUCATION 1978-81 BA Hons Degree in Sculpture, Ulster Polytechnic, York Street 1977-78 Foundation Course, Ulster Polytechnic, Jordanstown FORTHCOMING & CURRENT EXHIBITIONS 2020 ENDLESS, Kerlin Gallery, online viewing room, (27 May - 16 June 2020), (solo) SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Remains, Regional Cultural Centre, Letterkenny, Ireland Inquieta, Galeria Moises Perez de Albeniz, Madrid, Spain 2017 Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich, Switzerland Remains, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, South Korea No Return, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA Loose Ends, Matt’s Gallery, London, UK 2016 Passage, Alexander and Bonin, New York Lydney Park Estate, Gloucestershire, presented by Matt’s Gallery + BLACKROCK Loose Ends, Regional Centre, Letterkenny; Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland Home, Villa Merkel, Germany 2015 Again and Again, Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian, CAM, Lisbon Panopticon, Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA), Salt Lake City 2014 The Amnesiac and other recent video and photographic works, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA UNSEEN, Museum De Pont, Tilburg The Amnesiac, Galería Moisés Pérez de Albéniz, Madrid REMAINS, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 2013 UNSEEN, City Factory Gallery, Derry Secretion, Neue Galerie, Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel Secretion, The Annex, IMMA, Dublin Without Trace, Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich 2012 Secretion, Statens Museum for Kunst, National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen LAPSE, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin Photo/text/85/92, Matts Gallery, London One Place Twice, -

Pdf, 144.24 KB

Daniel Jewesbury artist | writer | lecturer | editor | curator Såggatan 65B – 1301, 414 67 Göteborg, Sweden. [email protected] / [email protected] +44 (0)7929 205361 / +46 (0)79 313 6253 danieljewesbury.org Born London, 23rd November, 1972 Education 1997 - 2001 Ph.D (Media Studies), University of Ulster at Coleraine 1992 - 1996 BA (Hons) Fine Art (Sculpture), National College of Art and Design, Dublin (2:1) Employment & other experience 2017 - Universitetslektor, Fri Konst, Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg 2018 - Fri Konst unit representative, Valand ACademy Research Board 2017 - Associate Researcher, Centre for Media Research, Ulster University 2013 - 2017 Lecturer in Film, Ulster University 2016 Curator, Tulca 2016, Festival of Visual Arts, Galway 2015 Co-curator, Periodical Review #5, Pallas ProjeCts, Dublin 2014 Fellow, Zentrum für Kunst und Urbanistik (ZK/U), Centre for Art & Urbanism, Berlin 2008 - 2014 Part-time PhD Supervisor, National College of Art & Design, Dublin (FaCulties of Fine Art / Visual Culture) 2003 - 2014 Co-editor, Variant magazine (www.variant.org.uk) 2010 - 2013 Visiting Fellow, Graduate SChool of Creative Arts & Media (GradCAM), Dublin 2010 - 2011 Chair, Digital Art Studios, Belfast 2010 Curator, re : public, group exhibition and event series, Temple Bar Gallery, Dublin 2009 Lead writer, EC Culture Programme funding bid (suCCessful), The Artist as Citizen, for GradCam, Dublin 2009 Nominee: Paul Hamlyn Award 2008 - 2009 Northern Representative, Visual Artists Ireland 2008 - 2009 Lead national researCher -

Art As Direct Political Action:” an Investigation Through Case Studies and Interviews

“ART AS DIRECT POLITICAL ACTION:” AN INVESTIGATION THROUGH CASE STUDIES AND INTERVIEWS SUBMITTED BY EMILY MEINHARDT CLAREMONT MCKENNA COLLEGE SIT IRELAND, FALL 2008 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF ROISIN KENNEDY, PHD ART HISTORY, UCD Art as Direct Political Action Emily Meinhardt 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………3 II. Methodology……………………………………………………………..........4 III. Main Body a. Part One: Case Studies i. Setting the Stage for Irish Contemporary Art…………..…………9 ii. Case Study: Robert Ballagh………………..……………….……10 iii. Case Study: Willie Doherty………………………………..…….14 iv. Ballagh and Doherty Case Studies in Contrast………...………...17 b. Part Two: Key Questions i. Art and Politics Re-examined……………………………...……20 ii. National Identity…………………………………………………21 iii. Public Money Complicating Political Art………………….…….24 iv. Is Irish Art Different?.....................................................................26 IV. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………...27 V. Bibliography………………………………………...……………………….30 VI. Appendix a. Images……………………………………………………………………33 b. Interviews i. Sean Kissane……………………………………………………..36 ii. Robert Ballagh………………………………………...…………40 iii. Dominic Bryan…………………………………...………………42 iv. Peter Richards……………………………………………………45 v. Theo Sims………………………………………………..………48 vi. Pauline Ross………………………………………………...……50 vii. Sighle Bhreathnach-Lynch…………………………………….…50 viii. Declan McGonagle………………………………………………52 Art as Direct Political Action Emily Meinhardt 3 ONE: INTRODUCTION In 1970, Artforum, an international magazine of contemporary art, conducted -

Abject Femininity in Willie Doherty's Same Difference and Closure

Études irlandaises 45-1 | 2020 Irish Arts: New Contexts Women’s Troubles: Abject Femininity in Willie Doherty’s Same Difference and Closure Kate Antosik-Parsons Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/8891 DOI: 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.8891 ISSN: 2259-8863 Publisher Presses universitaires de Caen Printed version Date of publication: 24 September 2020 Number of pages: 89-102 ISSN: 0183-973X Electronic reference Kate Antosik-Parsons, « Women’s Troubles: Abject Femininity in Willie Doherty’s Same Difference and Closure », Études irlandaises [Online], 45-1 | 2020, Online since 24 September 2020, connection on 01 October 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/8891 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.8891 Études irlandaises est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. Women’s Troubles: Abject Femininity in Willie Doherty’s Same Difference and Closure Abstract: The work of internationally acclaimed lens-based artist Willie Doherty proposes rich and nuanced understandings of the agency and participation of women in the Troubles in Northern Ireland. In a large number of visual and cultural representations of the ethno- nationalist violence of the Troubles, the conflict is often gendered as masculine, with women featuring primarily as victims and innocent bystanders. This essay examines Doherty’sSame Difference (1990) and Closure (2005), two key works that incorporate a female subject. It considers these works in relation to the concept of “abject femininity”, a non-normative femininity that is at odds with dominant representations of women as passive, nurturing care-givers or victims of conflict. -

The Catalogues of the Orchard Gallery: a Contribution to Critical and Historical Discourses in Northern Ireland, 1978-2003

The catalogues of the Orchard Gallery: a contribution to critical and historical discourses in Northern Ireland, 1978-2003 Gabriel N. Gee The Orchard Gallery opened in Derry in 1978. It was set up by Derry City Council, which appointed a then young artist and art teacher, Declan McGonagle, as its first exhibition director. The second largest city of Northern Ireland did not have any artistic infrastructure at the time, and the Orchard was launched as an attempt to make up for this absence. From the outset, the artistic programme of the gallery aimed to exhibit a range of practitioners, both emerging and established, and coming from diverse geographical horizons, who were asked to produce works specifically for the gallery. The work had to respond to ‘the gallery’s ethos, which was about the place, and the interaction and the relationship between the artist who comes from outside and the place’.1 Derry, or Londonderry, is a city of circa 80 000 people located on the northern confines of the Irish and British isles, on the border between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. Its history has long been rooted in a dual narrative. An early Celtic settlement brought the first naming of the site, Doire Calgach, or Calgach Oak Wood.2 With the expansion of the English rule in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the city was renamed Londonderry, an affirmation of the ties that now closely connected it to Britain. When the Orchard opened to the public, the city was at the heart of a conflict that since the 1960s had opposed in Northern Ireland with increasingly violent manifestations the Republican and Loyalist communities. -

Introduction

1 Introduction I returned many times to the same site until another fence was erected and a new building was put in place of the empty, silent reminder. I wondered about what had happened to the pain and terror that had taken place there. Had it absorbed or fi ltered into the ground, or was it possible for others to sense it as I did?1 If it – learning to live – remains to be done, it can happen only between life and death. Neither in life nor in death alone . What happens between the two, and between all the ‘two’s’ one likes, such as between life and death, can only maintain itself with some ghost, can only talk with or about some ghosts. 2 Two places at once, was it, or one place twice? 3 In 2013, a decade and a half after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, ‘Derry- Londonderry’ made headlines as the fi rst UK City of Culture. Strategically branding itself as a town- with- two- names – granting parity- of- esteem to histori- cally polarised perspectives on one place – Northern Ireland’s second city used this civic accolade to demonstrate (and build on) many positive developments of the ‘peace’ era. The offi cial logo for the year- long programme of cultural events, for instance, took the city’s striking ‘peace bridge’ as its inspiration. Opened in 2011, this dramatic, winding walkway over the river Foyle – connecting Derry’s broadly nationalist Cityside with its traditionally unionist Waterside – was an urban regeneration initiative emerging directly from the fi nancial dividends of the momentous, multi- party political Agreement of 1998. -

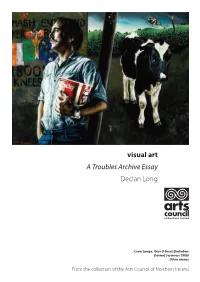

Visual Art a Troubles Archive Essay Declan Long

a fusillade of question-marks some reflections on the art of thevisual Troubles art A Troubles Archive Essay Declan Long CoverCover Image: Image: Arise Arise O Great Zimbabwe Dermot Seymour (1989) Cover Image: Rita Duffy - Big Fight Oil on canvas From the collection of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland From the collection of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland About the Author Declan Long is a lecturer at the National College of Art & Design, Dublin, where he is Course Director of the MA ‘Art in the Contemporary World’. He writes regularly on contemporary art for Irish and international magazines and has had numerous essays published by major institutions. He has been commissioned to contribute texts for the publications accompanying Irish and Northern Irish exhibitions at the Venice Art Biennale in 2005, 2007 and 2009 as well as for Ireland’s participation in the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2008. He is a board member of both the Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, and Create, the National Development Agency for Collaborative Arts. He is also a visual art correspondent for The Arts Show on RTE Radio One and has frequently featured as a panellist on RTE Television’s The View. Visual art ‘Our ghost-haunted land ...’ 1 Late in the afternoon of a still-wintry spring day in 2008, a funeral was staged at the Irish Museum of Modern Art for the recently departed artist Patrick Ireland. Chief mourner at this strange interment was, however, the surviving alter-ego of this singular figure: the artist’s “creator”, NewYork-based and Roscommon-born conceptual art pioneer Brian O’Doherty. -

IMMA MAIN GALLERIES, WEST WING Introduction

IMMA MAIN GALLERIES, WEST WING Introduction Ghosts from the Recent Past explores how urgencies of the past continue to inhabit the present. Set within a 40-year timeframe, the exhibition draws on IMMA’s Collection along with a number of key international loans. The works tell stories of colonisation and contested borders, of human relationships to the environment, of radical self- representation in the face of oppression and of love. Throughout the galleries, lists of ‘ghosts’ appear on translucent panels, naming spectres from the last four decades. Ghosts of Globalisation, Ghosts of Species, Ghosts of H-Block, The Holy Ghost and others signal a myriad of invisible forces that actively structure our present. Likewise, the artworks themselves are presented as ghostly objects, carrying languages of resistance, waywardness or joy. Since the 1980s, the fragmentation of societies into individualised consumers has accelerated at dizzying speeds with the dawn of the Internet, the abandonment of the Communist project in Europe and the widespread adoption of neoliberal politics in the West. The processes of fragmentation that followed have no doubt hindered our ability to think together (and to think radically) about the planetary dilemmas facing us. In this moment of uncertainty, a simple but burning question arises—”how can we care for a shared world?”* Yet within the current matrix of discontent, there is hope. The artworks confront us with paradox, resounding with themes of care, resistance, intimacy and play—the vital life signs that are now more important than ever. In anticipating what will be deemed essential in the wake of the pandemic, the American writer and civil rights activist Audre Lorde’s famous affirmation “Poetry is not a luxury”** has never felt more relevant. -

SELECTED READING Hill, 1972; Derek Hill, 'James Dixon', IAR Yearbook, Ix (1993), 179–82; Glennie, 1999; Bruce Arnold, Dere

SELECTED READING Hill, 1972; Derek Hill, ‘James Dixon’, IAR Most of Doherty’s compositions demonstrate abstract quali- Yearbook, ix (1993), 179–82; Glennie, 1999; Bruce Arnold, ties, and the frontal buildings, with their reticent stillness and Derek Hill (London 2010). balance, have been related to photographic work by abstract painter Sean Scully (qv). DOHERTY, JOHN (b. 1949), painter. It is the acute observa- John Doherty was born in Kilkenny and trained as an archi- tion of detail that gives John Doherty’s work its sense of intense tect at Bolton Street College of Technology, Dublin, before turn- realism. Meticulously rendered to show every scuff mark in the ing to art full-time. He was Artist in Residence at the National painted surface of a rotting door, or the moss clinging to the roof College of Art, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea in 1979. He tiles of a defunct village petrol station, Doherty’s work presents has lived in Australia and Sweden, as well as Ireland. images of nostalgia with a reserved objectivity. Yvonne Scott He is best known for his frontal depictions of the kind of buildings that were typical in Irish towns in the economically SELECTED READING Hilary Pyle, John Doherty: Recent Paintings, depressed years of his childhood, but he has also explored exh. cat. Taylor Galleries (Dublin 2005). unusual objects and structures for their form, such as the series of harbourside buoys, forming rusting still-life compositions on DOHERTY, WILLIE (b. 1959) (qv AAI iii), artist. In the their quaysides. As with many of his scenes, the series depicting years between 1969 and 2001, the ‘Troubles’ (see ‘The Troubles the gleaming upper bodies of whitewashed lighthouses are of and Irish Art’) made a profound and divisive impact on Irish actual structures. -

WILLIE DOHERTY B

WILLIE DOHERTY b. 1959, Derry, Northern Ireland Lives and works in Derry EDUCATION 1978-81 BA Hons Degree in Sculpture, Ulster Polytechnic, York Street 1977-78 Foundation Course, Ulster Polytechnic, Jordanstown CURRENT & FORTHCOMING EXHIBITIONS 2021 Where/Dove, Ulster Museum, Belfast, Northern Ireland (Solo, 4 June – 12 September) THE STATE WE’RE IN, (Billboard Project), The Void, Derry, Northern Ireland (Solo, 29 July – 11 August) Without Trace, De Pont Museum, Tilburg, The Netherlands (Group, 2 March – 5 September) Portrait of Northern Ireland: neither an elegy nor a manifesto, Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast, Northern Ireland (Group, 9 October – 2 November 2021) SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Where / Dove, Fondazione Modena Arti Visive, Modena, Italy 2020 ENDLESS, Kerlin Gallery, Online Viewing Room 2018 Remains, Regional Cultural Centre, Letterkenny, Ireland Inquieta, Galeria Moises Perez de Albeniz, Madrid, Spain 2017 Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich, Switzerland Remains, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, South Korea No Return, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA Loose Ends, Matt’s Gallery, London, UK 2016 Passage, Alexander and Bonin, New York Lydney Park Estate, Gloucestershire, presented by Matt’s Gallery + BLACKROCK Loose Ends, Regional Centre, Letterkenny; Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland Home, Villa Merkel, Germany 2015 Again and Again, Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian, CAM, Lisbon Panopticon, Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA), Salt Lake City 2014 The Amnesiac and other recent video and photographic works, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA UNSEEN,