The Rise of Cross-Border Insecurity What 800 Sahelians Have To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟S Center on Applied Feminism for Its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟s Center on Applied Feminism for its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference. “Applying Feminism Globally.” Feminism from an African and Matriarchal Culture Perspective How Ancient Africa’s Gender Sensitive Laws and Institutions Can Inform Modern Africa and the World Fatou Kiné CAMARA, PhD Associate Professor of Law, Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, SENEGAL “The German experience should be regarded as a lesson. Initially, after the codification of German law in 1900, academic lectures were still based on a study of private law with reference to Roman law, the Pandectists and Germanic law as the basis for comparison. Since 1918, education in law focused only on national law while the legal-historical and comparative possibilities that were available to adapt the law were largely ignored. Students were unable to critically analyse the law or to resist the German socialist-nationalism system. They had no value system against which their own legal system could be tested.” Du Plessis W. 1 Paper Abstract What explains that in patriarchal societies it is the father who passes on his name to his child while in matriarchal societies the child bears the surname of his mother? The biological reality is the same in both cases: it is the woman who bears the child and gives birth to it. Thus the answer does not lie in biological differences but in cultural ones. So far in feminist literature the analysis relies on a patriarchal background. Not many attempts have been made to consider the way gender has been used in matriarchal societies. -

The Political Sources of Religious Identification: Evidence from The

B.J.Pol.S. 49, 421–441 Copyright © Cambridge University Press, 2017 doi:10.1017/S0007123416000594 First published online 8 March 2017 The Political Sources of Religious Identification: Evidence from the Burkina Faso–Côte d’Ivoire Border JOHN F. MCCAULEY AND DANIEL N. POSNER* Under what conditions does religion become a salient social identity? By measuring religious attachment among the people living astride the Burkina Faso–Côte d’Ivoire border in West Africa, an arbitrary boundary that exposes otherwise similar individuals to different political contexts, this article makes a case for the importance of the political environment in affecting the weight that people attach to their religious identities. After ruling out explanations rooted in the proportion of different religious denominations, the degree of secularization and the supply of religious institutions on either side of the border, as well as differences in the degree of religious pluralism at the national level, it highlights the greater exposure of Ivorian respondents to the politicization of religion during Côte d’Ivoire’s recent civil conflict. Methodologically, the study demonstrates the power – and challenges – of exploiting Africa’s arbitrary borders as a source of causal leverage. Keywords: arbitrary borders; natural experiment; religion; Côte d’Ivoire; Burkina Faso; conflict; identities An estimated 85 per cent of the world’s population claims membership in a religious group.1 Yet the importance that people attach to their religious identity varies considerably. For some, religion is the defining characteristic of who they are; their politics and perspectives on the world are inextricably bound up in their faith. For others, religious group membership is merely one social attachment among many; their attitudes and behavior are little affected by their religious affiliation. -

The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness Onoma, Ato Kwamena

www.ssoar.info The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness Onoma, Ato Kwamena Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Onoma, A. K. (2018). The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness. Africa Spectrum, 53(3), 65-88. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-11588 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-ND Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-ND Licence Keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NoDerivatives). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/deed.de Africa Spectrum Onoma, Ato Kwamena (2018), The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness, in: Africa Spectrum, 53, 3, 65–88. URN: http://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-11588 ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs, in co-operation with the Arnold Bergstraesser Institute, Freiburg, and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. -

Degorce Alice, Kibora Ludovic & Langewiesche Katrin (Dir

Cahiers d’études africaines 241 | 2021 Varia DEGORCE Alice, KIBORA Ludovic & LANGEWIESCHE Katrin (DIR.). — Rencontres religieuses et dynamiques sociales au Burkina Faso Melina C. Kalfelis Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/33413 DOI : 10.4000/etudesafricaines.33413 ISSN : 1777-5353 Éditeur Éditions de l’EHESS Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 mars 2021 Pagination : 218-221 ISBN : 9782713228766 ISSN : 0008-0055 Référence électronique Melina C. Kalfelis, « DEGORCE Alice, KIBORA Ludovic & LANGEWIESCHE Katrin (DIR.). — Rencontres religieuses et dynamiques sociales au Burkina Faso », Cahiers d’études africaines [En ligne], 241 | 2021, mis en ligne le 15 mars 2021, consulté le 15 mars 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/ 33413 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.33413 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 15 mars 2021. © Cahiers d’Études africaines Degorce Alice, Kibora Ludovic & Langewiesche Katrin (dir.). — Rencontres reli... 1 DEGORCE Alice, KIBORA Ludovic & LANGEWIESCHE Katrin (DIR.). — Rencontres religieuses et dynamiques sociales au Burkina Faso Melina C. Kalfelis RÉFÉRENCE DEGORCE Alice, KIBORA Ludovic & LANGEWIESCHE Katrin (DIR.). — Rencontres religieuses et dynamiques sociales au Burkina Faso. Dakar, Amalion, 2019, 344 p., bibl., ill. 1 Tolerance, integrity, plurality—these are some of the ideals that Thomas Sankara had in mind when he changed the name of the former French colony of Upper Volta to Burkina Faso. The word burkĩna derives from the Mooré language (Fr.: hommes intègres), while faso is Dioula (Fr.: pays). The name therefore draws on two of the most commonly spoken languages in the country, which in itself symbolizes cultural and religious plurality. This plurality is Burkina Faso’s most unique selling point. -

Burkina Faso Burkina

Burkina Faso Burkina Faso Burkina Faso Public Disclosure Authorized Poverty, Vulnerability, and Income Source Poverty, Vulnerability, and Income Source Vulnerability, Poverty, June 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 16130_Burkina_Faso_Report_CVR.indd 3 7/14/17 12:49 PM Burkina Faso Poverty, Vulnerability, and Income Source June 2016 Poverty Global Practice Africa Region Report No. 115122 Document of the World Bank For Official Use Only 16130_Burkina_Faso_Report.indd 1 7/14/17 12:05 PM © 2017 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorse- ment or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. -

State of Food Security in Burkina Faso Fews Net Update for January-February, 2001

The USAID Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET) (Réseau USAID du Système d’Alerte Précoce contre la Famine) 01 BP 1615 Ouagadougou 01, Burkina Faso, West Africa Tel/Fax: 226-31-46-74. Email: [email protected] STATE OF FOOD SECURITY IN BURKINA FASO FEWS NET UPDATE FOR JANUARY-FEBRUARY, 2001 February 25, 2001 HIGHLIGHTS Food insecurity continues to worsen in the center plateau, north, and Sahel regions, prompting the government to call for distributions and subsidized sales of food between February and August in food insecure areas. Basic food commodities remained available throughout the country in February. Millet, the key food staple, showed no price movements that would suggest unusual scarcities in the main markets compared to prices in February 2000 or average February prices. Nevertheless, millet prices rose 40-85 % above prices a year ago in secondary markets in the north and Sahel regions, respectively. These sharp price rises stem from the drop in cereal production in October-November following the abrupt end of the rains in mid-August. Unfortunately, the lack of good roads reduces trader incentives to supply cereals to those areas. Consequently, prices have been increasing quickly due to increasing demand from households that did not harvest enough. Throughout the north and Sahel regions, most households generally depend on the livestock as their main source of income. Ironically this year, when millet prices are rising, most animal prices have fallen drastically due to severe shortages of water and forage. To make matters worse, animal exports to Ivory Coast, which used to be a very profitable business, are no longer a viable option following the ethnic violence that erupted in that country a few months ago. -

254 the Social Roots of Jihadist Violence in Burkina Fasos North

The Social Roots of Jihadist Violence in Burkina Faso’s North Africa Report N°254 | 12 October 2017 Translation from French Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 The Social Roots of the Crisis ........................................................................................... 3 A. Malam Ibrahim Dicko, from the Radio to Jihad ....................................................... 3 B. The Challenge to an Ossified and Unequal Social Order .......................................... 4 C. A Distant Relationship with the Government ........................................................... 7 D. An Especially Vulnerable Province on the Border with Mali .................................... 9 A Considerable Military Effort ......................................................................................... 11 A. The Sahel Region under Threat ................................................................................. 11 B. A Security Apparatus under Reconstruction ............................................................. 13 C. Regional and International Cooperation .................................................................. -

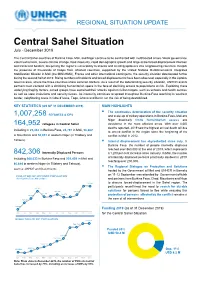

Central Sahel Situation July - December 2019

REGIONAL SITUATION UPDATE Central Sahel Situation July - December 2019 The Central Sahel countries of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger continue to be confronted with multifaceted crises. Weak governance, violent extremism, severe climate change, food insecurity, rapid demographic growth and large-scale forced displacement intersect and transcend borders, deepening the region’s vulnerability to shocks and creating spillovers into neighbouring countries. Despite the presence of thousands of troops from affected countries, supported by the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (the MINUSMA), France and other international contingents, the security situation deteriorated further during the second half of 2019. Rising numbers of incidents and forced displacements have been observed, especially in the Liptako- Gourma area, where the three countries share common borders. As a result of the deteriorating security situation, UNHCR and its partners must contend with a shrinking humanitarian space in the face of declining access to populations at risk. Exploiting these underlying fragility factors, armed groups have sustained their attacks against civilian targets, such as schools and health centres, as well as state institutions and security forces. As insecurity continues to spread throughout Burkina Faso reaching its southern border, neighboring areas in Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Ghana and Benin run the risk of being destabilized. KEY STATISTICS (AS OF 31 DECEMBER 2019) MAIN HIGHLIGHTS ▪ The continuous deterioration of the security situation 1,007,258 REFUGEES & IDPS and scale-up of military operations in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger drastically limits humanitarian access and 164,952 refugees in Central Sahel assistance in the most affected areas. With over 4,000 deaths reported, 2019 saw the highest annual death toll due Including in 25,442 in Burkina Faso, 24,797 in Mali, 56,662 to armed conflict in the region since the beginning of the in Mauritania and 58,051 in western Niger (in Tillabery and conflict in Mali in 2012. -

Country Profiles

Global Coalition EDUCATION UNDER ATTACK 2020 GCPEA to Protect Education from Attack COUNTRY PROFILES BURKINA FASO The frequency of attacks on education in Burkina Faso increased during the reporting period, with a sharp rise in attacks on schools and teachers in 2019. Over 140 incidents of attack – including threats, military use of schools, and physical attacks on schools and teachers – took place within a broader climate of insecurity, leading to the closure of over 2,000 educational facilities. Context The violence that broke out in northern Burkina Faso in 2015, and which spread southward in subsequent years,331 es- calated during the 2017-2019 reporting period.332 Ansarul Islam, an armed group that also operated in Mali, perpetrated an increasing number of attacks in Soum province, in the Sahel region, throughout 2016 and 2017.333 Other armed groups, including Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its affiliate, Groupfor the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM), as well as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), also committed attacks against government buildings, and civilian structures such as restaurants, schools, and churches, targeting military posts.334 Since the spring of 2017, the government of Burkina Faso has under- taken military action against armed groups in the north, including joint operations with Malian and French forces.335 Data from the UN Department for Safety and Security (UNDSS) demonstrated increasing insecurity in Burkina Faso during the reporting period. Between January and September 2019, 478 security incidents reportedly occurred, more than dur- ing the entire period between 2015 and 2018 (404).336 These incidents have extensively affected civilians. -

Project No. DSH-4000000964 Final Narrative Report

Border Security and Management in the Sahel - Phase II Project No. DSH-4000000964 Final Narrative Report In Fafa (Gao Region, Mali), a group of young girls take part in a recreational activity as a prelude to an awareness-raising session on the risks associated with the presence of small arms and light weapons in the community (March 2019) Funded by 1 PROJECT INFORMATION Name of Organization: Danish Refugee Council – Danish Demining Group (DRC-DDG) Project Title: Border Security and Management in the Sahel – Phase II Grant Agreement #: DSH-4000000964 Amount of funding allocated: EUR 1 600 000 Project Duration: 01/12/2017 – 30/09/2019 Countries: Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger Sites/Locations: Burkina Faso: Ariel, Nassoumbou, Markoye, Tokabangou, Thiou, Nassoumbou, Ouahigouya Mali: Fafa, Labbezanga, Kiri, Bih, Bargou Niger: Koutougou, Kongokiré, Amarsingue, Dolbel, Wanzarbe Number of beneficiaries: 17 711 beneficiaries Sustainable Development Goal: Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions Date of final report 30/01/2020 Reporting Period: 01/12/2017 – 30/09/2019 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Border Security and Management Programme was launched in 2014 by the Danish Demining Group’s (DDG). Designed to improve border management and security in the Liptako Gourma region (border area shared by Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger), the programme applies an innovative and community-based cross-border approach in the interests of the communities living in the border zones, with the aim of strengthening the resilience of those communities to conflict and -

Central Sahel Advocacy Brief

Central Sahel Advocacy Brief January 2020 UNICEF January 2020 Central Sahel Advocacy Brief A Children under attack The surge in armed violence across Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger is having a devastating impact on children’s survival, education, protection and development. The Sahel, a region of immense potential, has long been one of the most vulnerable regions in Africa, home to some countries with the lowest development indicators globally. © UNICEF/Juan Haro Cover image: © UNICEF/Vincent Tremeau The sharp increase in armed attacks on communities, schools, health centers and other public institutions and infrastructures is at unprecedented levels. Violence is disrupting livelihoods and access to social services including education and health care. Insecurity is worsening chronic vulnerabilities including high levels of malnutrition, poor access to clean water and sanitation facilities. As of November 2019, 1.2 million people are displaced, of whom more than half are children.1 This represents a two-fold increase in people displaced by insecurity and armed conflict in the Central Sahel countries in the past 12 months, and a five-fold increase in Burkina Faso alone.* Reaching those in need is increasingly challenging. During the past year, the rise in insecurity, violence and military operations has hindered access by humanitarian actors to conflict-affected populations. The United Nations Integrated Strategy for the Sahel (UNISS) continues to spur inter-agency cooperation. UNISS serves as the regional platform to galvanize multi-country and cross-border efforts to link development, humanitarian and peace programming (triple nexus). Partners are invited to engage with the UNISS platform to scale-up action for resilience, governance and security. -

Ethnic and Religious Intergenerational Mobility in Africa∗

Ethnic and Religious Intergenerational Mobility in Africa∗ Alberto Alesina Sebastian Hohmann Harvard University, CEPR and NBER London Business School Stelios Michalopoulos Elias Papaioannou Brown University, CEPR and NBER London Business School and CEPR September 27, 2018 Abstract We investigate the evolution of inequality and intergenerational mobility in educational attainment across ethnic and religious lines in Africa. Using census data covering more than 70 million people in 19 countries we document the following regularities. (1) There are large differences in intergenerational mobility both across and within countries across cultural groups. Most broadly, Christians are more mobile than Muslims who are more mobile than people following traditional religions. (2) The average country-wide education level of the group in the generation of individuals' parents is a strong predictor of group- level mobility in that more mobile groups also were previously more educated. This holds both across religions and ethnicities, within ethnicities controlling for religion and vice versa, as well as for two individuals from different groups growing up in the same region within a country. (3) Considering a range of variables, we find some evidence that mobility correlates negatively with discrimination in the political arena post indepdence, and that mobility is higher for groups that historically derived most of their subsistence from agriculture as opposed to pastoralism. Keywords: Africa, Development, Education, Inequality, Intergenerational Mobility. JEL Numbers. N00, N9, O10, O43, O55 ∗Alberto Alesina Harvard Univerity and IGIER Bocconi, Sebatian Hohmnn , London Busienss Schoiol, Stelios Michalopoulos. Brown University, Elias Papaioannou. London Business School. We thank Remi Jedwab and Adam Storeygard for sharing their data on colonial roads and railroads in Africa, Julia Cag´eand Valeria Rueda for sharing their data on protestant missions, and Nathan Nunn for sharing his data on Catholic and Protestant missions.