The Highland Council Contaminated Land Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Invertebrate Fauna of Dune and Machair Sites In

INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY (NATURAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL) REPORT TO THE NATURE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL ON THE INVERTEBRATE FAUNA OF DUNE AND MACHAIR SITES IN SCOTLAND Vol I Introduction, Methods and Analysis of Data (63 maps, 21 figures, 15 tables, 10 appendices) NCC/NE RC Contract No. F3/03/62 ITE Project No. 469 Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton Huntingdon Cambs September 1979 This report is an official document prepared under contract between the Nature Conservancy Council and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without permission from both the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology and the Nature Conservancy Council. (i) Contents CAPTIONS FOR MAPS, TABLES, FIGURES AND ArPENDICES 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 OBJECTIVES 2 3 METHODOLOGY 2 3.1 Invertebrate groups studied 3 3.2 Description of traps, siting and operating efficiency 4 3.3 Trapping period and number of collections 6 4 THE STATE OF KNOWL:DGE OF THE SCOTTISH SAND DUNE FAUNA AT THE BEGINNING OF THE SURVEY 7 5 SYNOPSIS OF WEATHER CONDITIONS DURING THE SAMPLING PERIODS 9 5.1 Outer Hebrides (1976) 9 5.2 North Coast (1976) 9 5.3 Moray Firth (1977) 10 5.4 East Coast (1976) 10 6. THE FAUNA AND ITS RANGE OF VARIATION 11 6.1 Introduction and methods of analysis 11 6.2 Ordinations of species/abundance data 11 G. Lepidoptera 12 6.4 Coleoptera:Carabidae 13 6.5 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae 14 6.6 Araneae 15 7 THE INDICATOR SPECIES ANALYSIS 17 7.1 Introduction 17 7.2 Lepidoptera 18 7.3 Coleoptera:Carabidae 19 7.4 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae -

WESTER ROSS Wester Ross Ross Wester 212 © Lonelyplanet Walk Tooneofscotland’Sfinestcorries, Coire Mhicfhearchair

© Lonely Planet 212 Wester Ross Wester Ross is heaven for hillwalkers: a remote and starkly beautiful part of the High- lands with lonely glens and lochs, an intricate coastline of rocky headlands and white-sand beaches, and some of the finest mountains in Scotland. If you are lucky with the weather, the clear air will provide rich colours and great views from the ridges and summits. In poor conditions the remoteness of the area makes walking a much more serious proposition. Whatever the weather, the walking can be difficult, so this is no place to begin learning mountain techniques. But if you are fit and well equipped, Wester Ross will be immensely rewarding – and addictive. The walks described here offer a tantalising taste of the area’s delights and challenges. An Teallach’s pinnacle-encrusted ridge is one of Scotland’s finest ridge walks, spiced with some scrambling. Proving that there’s much more to walking in Scotland than merely jumping out of the car (or bus) and charging up the nearest mountain, Beinn Dearg Mhór, in the heart of the Great Wilderness, makes an ideal weekend outing. This Great Wilderness – great by Scottish standards at least – is big enough to guarantee peace, even solitude, during a superb two-day traverse through glens cradling beautiful lochs. Slioch, a magnificent peak overlooking Loch Maree, offers a comparatively straightforward, immensely scenic ascent. In the renowned Torridon area, Beinn Alligin provides an exciting introduction to its consider- WESTER ROSS able challenges, epitomised in the awesome traverse of Liathach, a match for An Teallach in every way. -

Ballantyne 2018 EESTRSE La

Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh The Last Scottish Ice Sheet Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Journal: Edinburgh Manuscript ID TRE-2017-0022.R1 Manuscript Type: The Quaternary of Scotland Date Submitted by the Author: n/a Complete List of Authors: Ballantyne, Colin; University of St Andrews, Geography and Sustainable ForDevelopment Peer Review Small, David; Durham University, Department of Geography British-Irish Ice Sheet, Deglaciation, Dimlington Stade, Ice streams, Late Keywords: Devensian, Radiocarbon dating, Readvances, Terrestrial cosmogenic nuclide dating Cambridge University Press Page 1 of 88 Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh The Last Scottish Ice Sheet Colin K. Ballantyne 1 and David Small 2 1 School of GeographyFor and Sustainable Peer Development, Review University of St Andrews, St Andrews KY16 9AL, UK. Corresponding Author ( [email protected] ) 2 Department of Geography, Durham University, Lower Mountjoy, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, UK. Running head: The last Scottish Ice Sheet Cambridge University1 Press Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Page 2 of 88 ABSTRACT: The last Scottish Ice Sheet (SIS) expanded from a pre-existing ice cap after ~35 ka. Highland ice dominated, with subsequent build up of a Southern Uplands ice mass. The Outer Hebrides, Skye, Mull, the Cairngorms and Shetland supported persistent independent ice centres. Expansion was accompanied by ice-divide migration and switching flow directions. Ice nourished in Scotland reached the Atlantic Shelf break in some sectors but only mid-shelf in others, was confluent with the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet (FIS) in the North Sea Basin, extended into northern England, and fed the Irish Sea Ice Stream and a lobe that reached East Anglia. -

Highland Council Transport Programme Consultation Feedback Report

Highland Council Transport Programme Consultation Feedback Report Contents Page number Introduction 3 Inverness and Nairn 8 Easter Ross and Black Isle 31 Badenoch and Strathspey 51 Eilean a’ Cheo 64 Wester Ross and Lochalsh 81 Lochaber 94 Caithness 109 Section 1 Introduction Introduction The Council currently spends £15.003m on providing mainstream home to school, public and dial a bus transport across Highland. At a time of reducing budgets, the Council has agreed a target to reduce the budget spent on the provision of transport by 15%. The Transport Programme aims to consider the needs of communities across Highland in the preparation for re-tendering the current services offered. It is important to understand the needs and views of communities to ensure that the services provided in the future best meet the needs of communities within the budget available. The public engagement for the transport programme commenced Monday 26th October 2015 and over a 14-week period sought to obtain feedback from groups, individuals and transport providers. This consultation included local Member engagement, a series of 15 public meetings and a survey (paper and online). The feedback from this consultation will contribute to the process of developing a range of services/routes. The consultation survey document asked questions on: • How suitable the current bus services are – what works, what should change and the gaps • Is there anything that prevents or discourages the use of bus services • What type of bus service will be important in the future • What opportunities are there for saving by altering the current network Fifteen public meetings where held throughout Highland. -

Quartz Technology in Scottish Prehistory

Quartz technology in Scottish prehistory by Torben Bjarke Ballin Scottish Archaeological Internet Report 26, 2008 www.sair.org.uk Published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, www.socantscot.org.uk with Historic Scotland, www.historic-scotland.gov.uk and the Council for British Archaeology, www.britarch.ac.uk Editor Debra Barrie Produced by Archétype Informatique SARL, www.archetype-it.com ISBN: 9780903903943 ISSN: 1473-3803 Requests for permission to reproduce material from a SAIR report should be sent to the Director of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, as well as to the author, illustrator, photographer or other copyright holder. Copyright in any of the Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports series rests with the SAIR Consortium and the individual authors. The maps are reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of The Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. ©Crown copyright 2001. Any unauthorized reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Historic Scotland Licence No GD 03032G, 2002. The consent does not extend to copying for general distribution, advertising or promotional purposes, the creation of new collective works or resale. ii Contents List of illustrations. vi List of tables . viii 1 Summary. 1 2 Introduction. 2 2.1 Project background, aims and working hypotheses . .2 2.2 Methodology . 2 2.2.1 Raw materials . .2 2.2.2 Typology. .3 2.2.3 Technology . .3 2.2.4 Distribution analysis. 3 2.2.5 Dating. 3 2.3 Project history . .3 2.3.1 Pilot project. 4 2.3.2 Main project . -

Property Document

Offers Over Glendale House £420,000 (Freehold) South Erradale, Gairloch, IV21 2AU Substantial 3-Star VisitScotland Extending to 5 self-catering Spacious and private self- Set in easily maintained Easy-to-operate and flexible self-catering apartments offering a units, bar/restaurant area contained 1-bedroom owner’s grounds with large property business model offering a lifestyle business opportunity with heated swimming pool accommodation set to the footprint genuine “home and income” within a stunning West Coast under poly-tunnel ground floor opportunity location just off the North Coast 500 tourist route DESCRIPTION Glendale House is a substantial property which has been extended over the years from a croft house built in the 1960’s. The property is set within some of the most stunning landscapes on offer in the UK. The main building has 5 potential self-catering apartments and self-contained owner’s accommodation, all boasting seaward views. The extant operation is limited to three letting apartments through choice but new owners could easily revitalise the operation and bring the two remaining units on stream. The décor and equipment levels in these areas are all of a good standard but new owners may wish to stamp their own personality on the business. The property includes the amenity of a heated swimming pool plus areas of decking. The present business operation undertakes purely a self-catering operation but the space and amenities would allow new owners to operate a bar/ restaurant/ cafe service, if so desired. The space set aside for the bar could also be turned into additional accommodation subject to planning consents. -

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Community Services: Highland Area RAUC Local Co-Ordination Meeting Job No

Scheme THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Community Services: Highland Area RAUC Local Co-ordination Meeting Job No. File No. No. of Pages 5 SUMMARY NOTES OF MEETING + Appendices Meeting held to Discuss: Various Date/Time of Meeting: 24/10/19 10.00am Issue Date* Author Kirsten Donald Draft REF ACTIONS 1.0 Attending / Contact Details Highland Council Community Services; Area Roads Alistair MacLeod [email protected] Jonathan Gunn [email protected] Trevor Fraser [email protected] Kevin Fulton [email protected] Openreach Duncan MacLennan [email protected] Scottish & Southern Energy Fiona Geddes [email protected] Scottish Water Darren Pointer [email protected] Bear Scotland Peter Macnab [email protected] Mike Gray [email protected] Apologies / Others Alison MacLeod [email protected] Andrew Ewing [email protected] Roddy Davidson [email protected] Adam Lapinski [email protected] Andrew Maciver [email protected] Courtney Mitchell [email protected] Alex Torrance [email protected] Jim Moran [email protected] 2.0 Minutes of Previous Meetings Previous Minutes Accepted 3.0 HC Roads Inverness Planned Works – Surface Dressing 2019/2020 Financial Year The surfacing program is almost complete. Alistair mentioned that the works on Academy Street went well with only 1 complaint. Events Still waiting for a list of events which will then be attached to appendix 1. Lochaber No programme or update submitted Nairn and Badenoch & Strathspey Surfacing works are almost complete Ross & Cromarty Still waiting for detailed plans for next financials years programme of works. -

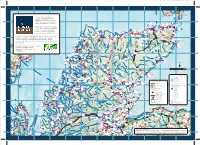

A It H E S S T R L Nd Ast E R O S S Este R R O Ss L E S Skye

A B C D E F G H J K L To Stromness e St. Margaret’s Hope p o Hoxa H Hoy s ’ t e 8 r 8 a Widewall g r a South M . Orkney South Walls t Ronaldsay S Islands o Created by the North Highland Swona T Initiative, the North Coast 500 P e n t l Burwick a n d F (NC500) is the brand new touring i r t h route that aims to bring together the Island of Caithness Dunnet Head Stroma best of the Highlands of Scotland. Horizons Seadrift Cape Wrath Dunnet Head Centre Castle of Mey B855 Duncansby Gills Head Beginning the route in Inverness, the Faraid Head Brough Dunnet Huna John o’ Groats capital of the Highlands, the NC500 Strathy Point Scrabster Thurso Dunnet Mey 7 Bay Bay 7 steers along the stunning coastal Strathnaver Durness Totegan Butt of Lewis Sandwood Museum Tofts edges of the North Highlands in a Bay A836 Castletown Strathy Thurso route covering just over 500 miles. Sandwood Castlehill A99 Loch Keoldale e Auckengill Port of Ness u Heritage Centre g Skerrray Melvich Reay Westfield Caithness ll n Bower ! o B874 o T Keiss Broch ib f r o Bettyhill Ideal for all travellers, the NC500 highlights the unique and exciting E B876 A838 e Broubster B870 h l c A838 y o K experiences available in the Highlands, from the awe-inspiring L Hope Borgie Halkirk Sinclair’s ! Bay Oldshoremore Broubster Leans Georemas B870 mountain ranges, to the Mediterranean-style beaches; from the Kinlochbervie Scotscalder S Junction Sinclair & Girnigoe (Ruins) B801 Cranstackie Loch Castle Varrich Tongue B874 t Station Siader . -

Wester Ross National Scenic Area

Wester Ross National Scenic Area Revised Draft Management Strategy November 2002 IMPORTANT PREFACE This draft document was considered by the Ross and Cromarty Area Planning Committee on 11th February 2003. At that time it was agreed that – X Efforts should be continued with Scottish Natural Heritage and the Wester Ross Alliance to progress and deliver a number of immediate projects, and that the forthcoming preparation of the Wester Ross Local Plan should be used to progress some of the policy oriented actions arising out of the Management Strategy; and that X Efforts are made with Dumfries and Galloway Council together with Scottish Natural Heritage to lobby the Scottish Executive to formally respond to the 1999 SNH Advice to Government on National Scenic Areas, to reaffirm its support for NSAs/Management Strategies, and to take action itself to positively influence policy and resources in favour of NSAs. Following further consideration at the Council’s West Coast Sub Committee on 1st April 2003 the draft document was considered further by the Ross and Cromarty Area Committee on 7th April 2003. At that time it was agreed that – X Any decision on the adoption of the Management Strategy should be deferred pending consideration of the Wester Ross Local Plan review. Therefore this draft document has not been adopted or approved by The Highland Council. It will be considered further by the Council at a later date in the context of the policy coverage of the replacement Wester Ross Local Plan. In the meantime the document was accepted and approved by Scottish Natural Heritage at the meeting of the North Areas Board on 21st November 2002. -

Wilderness Walking View Trip Dates High Points of Torridon Book Now & Wester Ross

Wilderness Walking View Trip Dates High Points of Torridon Book Now & Wester Ross Trip Grade: Red 7 High Points of Torridon & Wester Ross In the Highlands of North West Scotland lie hundreds of square miles of mountains and lochs, far from civilisation and accessed by just one or two main roads. Save for the occasional hiker this is wild land, the domain of eagles, a landscape best taken in from up high. On this adventure into the wildest places of the Highlands, we will explore iconic and rarely climbed peaks, enjoying wild and challenging hiking. At the end of each day, we will return to our welcoming hotels to enjoy hearty Highland cooking and a peaceful night. Highlights • Immerse yourself in the wilderness of the North West Highlands - a land of magnificent mountains, sweeping glens and silvery lochs • Enjoy superb hiking, ascending both classic and rarely climbed peaks with panoramic views • Discover the Highland culture - warm hospitality, and living life close to the land Book with confidence • We guarantee this trip will run as soon as 3 people have booked • Maximum of 8 places available per departure PLEASE NOTE – The itinerary may be subject to change at the discretion of the Wilderness Scotland Guide with regard to weather conditions and other factors. Planned Itinerary Day 1 | Peaks and Crofts Day 2 | The Hills of the Birds Day 3 | A Wild Coastline Day 4 | Hiking “The Spear” Day 5 | A Torridon Summit Day 6 | A Peak of Our Own Day 7 | A Final High Point Arrival Info • Your Guide will meet you at the centre of Inverness Railway Station by the fixed seating area • 9:00am on Day 1 of your trip Departure Info • You will be returned to Inverness Railway Station • 5:00pm on the final day of your trip PLEASE NOTE – The itinerary may be subject to change at the discretion of the Wilderness Scotland Guide with regard to weather conditions and other factors. -

25 Myriapoda from Wester Ross and Skye, Scotland

BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH MYRIAPOD AND ISOPOD GROUP Volume 20 2004 MYRIAPODA FROM WESTER ROSS AND SKYE, SCOTLAND A.D.Barber Rathgar, Exeter Road, Ivybridge, Devon, PL21 0BD In the Preliminary Atlas of Millipedes (British Myriapod Group, 1988) some seven species are shown from the Isle of Skye and six from those coastal areas of Wester Ross encompassed in the 100km National Grid square NG (18). For centipedes (Barber & Keay, 1988) the corresponding numbers are six and one. A proportion of the Skye records were made by Bruce Philp in the early 1980s in the course of other surveys. The species of which I am aware of him having found are marked P. Subsequently, a number of records were made by Gordon Corbet (details held by National Recording Schemes and included here). Dick Jones (Jones, 1992) made several records from Wester Ross in his report on Myriapods from North Scotland and these are also noted (indicated RJ). We have a few Wester Ross records from the10km grid square NH (28) which are included and identified with an asterisk (*) and from NC (29) (indicated **) although any such records in the preliminary atlas are omitted. Skye and the adjacent island of Raasay are part of Watsonian vice-county 104 (along with Rum, Canna, Eigg, etc.) whilst Wester Ross is VC 105. 10km NG squares are shown for the unpublished records. In August 2003, I had the opportunity to visit these areas and make a few collections. The weather had been extremely dry for some weeks and was then followed by heavy rain, conditions hardly suitable for finding large numbers of animals. -

North West Highlands

ESSENCE OF SCOTLAND Northwest Highlands Front cover: Oldshoremore Beach near Kinlochbervie This page: Loch Maree, Wester Ross At the very edge of Europe, the majestic peaks, magical lochs and sparkling beaches of the Northwest Highlands remain relatively untouched and unvisited. Easily accessible, these landscapes are a walker’s paradise and a perfect destination for those in search of solitude. IDEAL FOR LOCATION MAP Numbers refer to attractions A838 > Those in search of ‘escape’ listed overleaf. > Nature & wildlife lovers Places in bold print indicate welcome accommodation bases. > A true ‘wilderness’ experience DON’T MISS £ Paid Entry Seasonal Disabled Access Refreshments Gift Shop WC Rainy Days A894 > Insight into Scotland’s geological heritage A838 A837 To view accommodation in this A837 area, go to visitscotland.com or to order the local 1. Handa Island – 2. Inverpolly – Situated 3. Loch Maree – Perhaps 4. Sandwood Bay – 5. Sail to the Summer accommodation brochure, call Accessible by boat from within Scotland’s first the most spectacularly Beyond the important fishing Isles – Boat trips depart 0845 22 55 121. A835 Tarbet, just north of Scourie, UNESCO-designated scenic of all Scottish lochs, port of Kinlochbervie in the from Ullapool and Achiltibuie A832 Handa is home to one of Geopark, and containing Loch Maree greets far north-west, the road throughout the summer Britain’s biggest seabird some of the country’s unsuspecting visitors comes to an end near the months to visit this tiny colonies during spring and wildest and most awe- travelling north-west on the crofting township of group of largely uninhabited MORE INFORMATION A832 early summer.