Port Henderson : Past & Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel

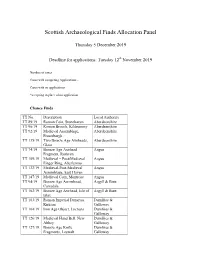

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel Thursday 5 December 2019 Deadline for applications: Tuesday 12th November 2019 Number of cases – Cases with competing Applications - Cases with no applications – *accepting in place of no application Chance Finds TT No. Description Local Authority TT 89/19 Roman Coin, Stonehaven Aberdeenshire TT 90/19 Roman Brooch, Kildrummy Aberdeenshire TT 92/19 Medieval Assemblage, Aberdeenshire Fraserburgh TT 135/19 Two Bronze Age Axeheads, Aberdeenshire Glass TT 74/19 Bronze Age Axehead Angus Fragment, Ruthven TT 109/19 Medieval – Post-Medieval Angus Finger Ring, Aberlemno TT 132/19 Medieval-Post-Medieval Angus Assemblage, East Haven TT 147/19 Medieval Coin, Montrose Angus TT 94/19 Bronze Age Arrowhead, Argyll & Bute Carradale TT 102/19 Bronze Age Axehead, Isle of Argyll & Bute Islay TT 103/19 Roman Imperial Denarius, Dumfries & Kirkton Galloway TT 104/19 Iron Age Object, Lochans Dumfries & Galloway TT 126/19 Medieval Hand Bell, New Dumfries & Abbey Galloway TT 127/19 Bronze Age Knife Dumfries & Fragments, Leswalt Galloway TT 146/19 Iron Age/Roman Brooch, Falkirk Stenhousemuir TT 79/19 Medieval Mount, Newburgh Fife TT 81/19 Late Bronze Age Socketed Fife Gouge, Aberdour TT 99/19 Early Medieval Coin, Fife Lindores TT 100/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Fife St Andrews TT 101/19 Late Medieval/Post-Medieval Fife Seal Matrix, St Andrews TT 111/19 Iron Age Button and Loop Fife Fastener, Kingsbarns TT 128/19 Bronze Age Spearhead Fife Fragment, Lindores TT 112/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Highland Muir of Ord TT -

Daytoday Catering Web-1.Pdf

bread garden market Catering breakfast savory breakfast bagel platter signature bread scrambled eggs, bacon or Bread 15 assorted bagels with 2oz pudding Garden Market sausage, croissant portions of cream cheese: plain, $35.00 pan [serves 10] french toast, and herbed potatoes veggie or strawberry $7.99 person $25 *minimum order of 10 servings *add lox and garnishes for croissant french toast $5 person $35.00 pan [serves 10] homemade quiche assorted quiche baked in our pastry platter scratch made scones flaky pie crust. choose from 20 pieces of assorted mini blueberry, chocolate, or margherita quiche lorraine, five cheese, pastries: muffins, croissants, $2.99 each or vegetable danish, and cinnamon rolls full size $18 (serves 6) $25 butter croissant personal size $2.99 each fresh baked muffins $2.99 each bgm scramble zucchini, blueberry, banana $9.99 dozen half size egg scramble with ham, peppers, chocolate chip, pumpkin pecan, caramelized onion, and lemon raspberry, or lemon pepper jack cheese $1.99 each filled croissant with a side of herbed potatoes $11.99 dozen for half-size chocolate, almond, or ham and swiss $6.99 person $3.49 each $21.99 dozen half size BG doughnuts pecan sticky buns egg casserole classic glazed doughnuts $2.99 each egg bake with potatoes, made from scratch bacon or house made sausage, $.99 each danish and cheese $10.99 dozen $6.99 person Assorted fruit or cheese fillings *minimum order of 5 dozen $2.49 each *minimum order of 10 servings Monday-Thursdays sweet breads A la carte sides breakfast burrito pumpkin, apple -

Driving Edinburgh to Gairloch a Personal View Ian and Lois Neal

Driving Edinburgh to Gairloch a personal view Ian and Lois Neal This is a personal account of driving the route from Edinburgh to Gairloch, supplemented by words and pictures trawled from the Internet. If we have used your material recklessly, we apologise; do let us know and we will acknowledge or remove it. Introduction to the Area As a settlement, Gairloch has a number of separately named and distinct points of focus. The most southerly is at Charlestown where you can find Gairloch's harbour. In more recent times the harbour was the base for the area's fishing fleet. Gairloch was particularly renowned for its cod. Much of the catch was dried at Badachro on the south shore of Loch Gairloch before being shipped to Spain. Today the harbour is used to land crabs, lobsters and prawns. Much of this also goes to the Spanish market, but now it goes by road. From here the road makes its way past Gairloch Golf Club. Nearby are two churches, the brown stone Free Church with its magnificent views over Loch Gairloch and the white-harled kirk on the inland side of the main road. Moving north along the A832 as it follows Loch Gairloch you come to the second point of focus, Auchtercairn, around the junction with the B8021. Half a mile round the northern side of Loch Gairloch brings you to Strath, which blends seamlessly with Smithtown. Here you will find the main commercial centre of Gairloch. Gairloch's history dates back at least as far as the Iron Age dun or fort on a headland near the golf club. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

2013 Individual Results Highland Cross 2013 Individual Prizes

Highland Cross 2013 Individual Results Highland Cross 2013 Individual Prizes 1 Joe Symonds Inverness 03:16:55 First - Gent Joe Symonds Inverness 03:16:55 2 Ewan McCarthy Kingussie 03:34:15 First - Lady Claire Gordon Bathgate 04:01:40 3 Gordon Lennox Invergordon 03:35:04 First - Over 50 Gent David Oliphant Stirling 04:03:10 4 Stewart Whitlie Edinburgh 03:40:21 First - Over 50 Lady Marion Nicolson Inverness 04:55:09 5 Dan Gay Edinburgh 03:41:33 First - Over 60 Alex Brett Dingwall 04:40:51 6 Alan Semple Aberdeen 03:42:54 First - Superveteran Gent Adrian Davis Dunkeld 03:46:07 7 Michael O'Donnell Inverness 03:46:06 First - Superveteran Lady Mary Johnson Dingwall 04:37:14 8 Adrian Davis Dunkeld 03:46:07 First - Veteran Gent Stewart Whitlie Edinburgh 03:40:21 9 David Rodgers Fort William 03:46:15 First - Veteran Lady Lorna Stanger Thurso 04:23:16 10 Andrew MacRae Inverness 03:46:51 Mark Hamilton Memorial Trophy Iain MacDonald Dingwall 04:47:49 11 Graham Bee Elgin 03:47:01 Special Endeavour Trophy Roddy Main Inverness 12 Paul Miller Beauly 03:50:04 13 Anthony Lawther Kingussie 03:50:06 Highland Cross 2013 Team Prizes 14 Gary MacDonald Kinlochleven 03:58:22 15 Richard Lonnen Dingwall 03:58:29 First - Open Team Ken's Team 16 Steven McIntyre Inverness 04:00:40 Second - Open Team Against the Odds 17 Claire Gordon Bathgate 04:01:40 Third - Open Team Stirling Triers 18 Mike Legget Edinburgh 04:01:52 First - Overall Gents Team Looking Good, Looking Skinny 19 Jamie Paterson Dingwall 04:01:53 First - Overall Ladies Team Cross Land High 20 David Oliphant -

Gaelic Names of Plants

[DA 1] <eng> GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS [DA 2] “I study to bring forth some acceptable work: not striving to shew any rare invention that passeth a man’s capacity, but to utter and receive matter of some moment known and talked of long ago, yet over long hath been buried, and, as it seemed, lain dead, for any fruit it hath shewed in the memory of man.”—Churchward, 1588. [DA 3] GAELIC NAMES OE PLANTS (SCOTTISH AND IRISH) COLLECTED AND ARRANGED IN SCIENTIFIC ORDER, WITH NOTES ON THEIR ETYMOLOGY, THEIR USES, PLANT SUPERSTITIONS, ETC., AMONG THE CELTS, WITH COPIOUS GAELIC, ENGLISH, AND SCIENTIFIC INDICES BY JOHN CAMERON SUNDERLAND “WHAT’S IN A NAME? THAT WHICH WE CALL A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME WOULD SMELL AS SWEET.” —Shakespeare. WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXXXIII All Rights reserved [DA 4] [Blank] [DA 5] TO J. BUCHANAN WHITE, M.D., F.L.S. WHOSE LIFE HAS BEEN DEVOTED TO NATURAL SCIENCE, AT WHOSE SUGGESTION THIS COLLECTION OF GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS WAS UNDERTAKEN, This Work IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. [DA 6] [Blank] [DA 7] PREFACE. THE Gaelic Names of Plants, reprinted from a series of articles in the ‘Scottish Naturalist,’ which have appeared during the last four years, are published at the request of many who wish to have them in a more convenient form. There might, perhaps, be grounds for hesitation in obtruding on the public a work of this description, which can only be of use to comparatively few; but the fact that no book exists containing a complete catalogue of Gaelic names of plants is at least some excuse for their publication in this separate form. -

Your Detailed Itinerary Scotland Will Bring You to the A96 to the North- Its Prehistory, Including the Standing This Is the ‘Outdoor Capital’ of the UK

Classic Scotland Classic Your Detailed Itinerary Scotland will bring you to the A96 to the north- its prehistory, including the Standing This is the ‘outdoor capital’ of the UK. east. At Keith, you can enjoy a typical Stones at Calanais, a setting of great Nearby Nevis Range, for example, is a Day 1 distillery of the area, Strathisla. presence and mystery which draws ski centre in winter, while, without Day 13 From Jedburgh, with its abbey visitor many to puzzle over its meaning. snow, it has Britain’s longest downhill Glasgow, as Scotland’s largest city, centre, continue northbound to (Option here to stay for an extra day mountain bike track, from 2150 ft offers Scotland’s largest shopping experience the special Borders to explore the island.) Travel south to (655m), dropping 2000ft (610m) over choice, as well as museums, galleries, landscape of rolling hills and wooded Day 4/5 Tarbert in Harris for the ferry to Uig almost 2 miles (3km). It’s fierce and culture, nightlife, pubs and friendly river valley. Then continue to Go west to join the A9 at Inverness in Skye. demanding but there are plenty of locals. Scotland’s capital, Edinburgh, with its for the journey north to Scrabster, other gentler forest trails nearby. Fort choice of cultural and historic ferryport for Orkney. From Stromness, William also offers what is arguably attractions. Explore the Old Town, the Stone Age site of Skara Brae lies Scotland’s most scenic rail journey, the city’s historic heart, with its quaint north, on the island’s west coast. -

The Invertebrate Fauna of Dune and Machair Sites In

INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY (NATURAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL) REPORT TO THE NATURE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL ON THE INVERTEBRATE FAUNA OF DUNE AND MACHAIR SITES IN SCOTLAND Vol I Introduction, Methods and Analysis of Data (63 maps, 21 figures, 15 tables, 10 appendices) NCC/NE RC Contract No. F3/03/62 ITE Project No. 469 Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton Huntingdon Cambs September 1979 This report is an official document prepared under contract between the Nature Conservancy Council and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without permission from both the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology and the Nature Conservancy Council. (i) Contents CAPTIONS FOR MAPS, TABLES, FIGURES AND ArPENDICES 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 OBJECTIVES 2 3 METHODOLOGY 2 3.1 Invertebrate groups studied 3 3.2 Description of traps, siting and operating efficiency 4 3.3 Trapping period and number of collections 6 4 THE STATE OF KNOWL:DGE OF THE SCOTTISH SAND DUNE FAUNA AT THE BEGINNING OF THE SURVEY 7 5 SYNOPSIS OF WEATHER CONDITIONS DURING THE SAMPLING PERIODS 9 5.1 Outer Hebrides (1976) 9 5.2 North Coast (1976) 9 5.3 Moray Firth (1977) 10 5.4 East Coast (1976) 10 6. THE FAUNA AND ITS RANGE OF VARIATION 11 6.1 Introduction and methods of analysis 11 6.2 Ordinations of species/abundance data 11 G. Lepidoptera 12 6.4 Coleoptera:Carabidae 13 6.5 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae 14 6.6 Araneae 15 7 THE INDICATOR SPECIES ANALYSIS 17 7.1 Introduction 17 7.2 Lepidoptera 18 7.3 Coleoptera:Carabidae 19 7.4 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae -

A FREE CULTURAL GUIDE Iseag 185 Mìle • 10 Island a Iles • S • 1 S • 2 M 0 Ei Rrie 85 Lea 2 Fe 1 Nan N • • Area 6 Causeways • 6 Cabhsi WELCOME

A FREE CULTURAL GUIDE 185 Miles • 185 Mìl e • 1 0 I slan ds • 10 E ile an an WWW.HEBRIDEANWAY.CO.UK• 6 C au sew ays • 6 C abhsiarean • 2 Ferries • 2 Aiseag WELCOME A journey to the Outer Hebrides archipelago, will take you to some of the most beautiful scenery in the world. Stunning shell sand beaches fringed with machair, vast expanses of moorland, rugged hills, dramatic cliffs and surrounding seas all contain a rich biodiversity of flora, fauna and marine life. Together with a thriving Gaelic culture, this provides an inspiring island environment to live, study and work in, and a culturally rich place to explore as a visitor. The islands are privileged to be home to several award-winning contemporary Art Centres and Festivals, plus a creative trail of many smaller artist/maker run spaces. This publication aims to guide you to the galleries, shops and websites, where Art and Craft made in the Outer Hebrides can be enjoyed. En-route there are numerous sculptures, landmarks, historical and archaeological sites to visit. The guide documents some (but by no means all) of these contemplative places, which interact with the surrounding landscape, interpreting elements of island history and relationships with the natural environment. The Comhairle’s Heritage and Library Services are comprehensively detailed. Museum nan Eilean at Lews Castle in Stornoway, by special loan from the British Museum, is home to several of the Lewis Chessmen, one of the most significant archaeological finds in the UK. Throughout the islands a network of local historical societies, run by dedicated volunteers, hold a treasure trove of information, including photographs, oral histories, genealogies, croft histories and artefacts specific to their locality. -

WESTER ROSS Wester Ross Ross Wester 212 © Lonelyplanet Walk Tooneofscotland’Sfinestcorries, Coire Mhicfhearchair

© Lonely Planet 212 Wester Ross Wester Ross is heaven for hillwalkers: a remote and starkly beautiful part of the High- lands with lonely glens and lochs, an intricate coastline of rocky headlands and white-sand beaches, and some of the finest mountains in Scotland. If you are lucky with the weather, the clear air will provide rich colours and great views from the ridges and summits. In poor conditions the remoteness of the area makes walking a much more serious proposition. Whatever the weather, the walking can be difficult, so this is no place to begin learning mountain techniques. But if you are fit and well equipped, Wester Ross will be immensely rewarding – and addictive. The walks described here offer a tantalising taste of the area’s delights and challenges. An Teallach’s pinnacle-encrusted ridge is one of Scotland’s finest ridge walks, spiced with some scrambling. Proving that there’s much more to walking in Scotland than merely jumping out of the car (or bus) and charging up the nearest mountain, Beinn Dearg Mhór, in the heart of the Great Wilderness, makes an ideal weekend outing. This Great Wilderness – great by Scottish standards at least – is big enough to guarantee peace, even solitude, during a superb two-day traverse through glens cradling beautiful lochs. Slioch, a magnificent peak overlooking Loch Maree, offers a comparatively straightforward, immensely scenic ascent. In the renowned Torridon area, Beinn Alligin provides an exciting introduction to its consider- WESTER ROSS able challenges, epitomised in the awesome traverse of Liathach, a match for An Teallach in every way. -

Mr Alexander Mackenzie Land 45M NW of Braeburn, 4 Aultgrishan, Melvaig

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda Item 5.1 NORTH PLANNING APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE Report No PLN/050/16 18 OCTOBER 2016 16/00342/FUL: Mr Alexander Mackenzie Land 45M NW of Braeburn, 4 Aultgrishan, Melvaig. Report by Area Planning Manager SUMMARY Description : Erection of house Recommendation - GRANT Ward : 06 - Wester Ross, Strathpeffer And Lochalsh Development category : Local Development Pre-determination hearing : Hearing not required Reason referred to Committee : Five or more representations 1. PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 1.1 Planning permission is sought for the erection of a three bedroomed property. The house has traditional features including a 45 degree roof pitch, vertical emphasis to the windows and a modest pitched roof porch. A simple palette of materials are proposed; grey tiles, wet dash harl for the walls and vertical larch cladding to the porch. 1.2 The house will be served by a private drainage system with a septic tank and soakaway located at the rear of the property. An area of garden ground will be created around the house by the construction of a fence. 1.3 The site will be accessed from the public road by an existing junction which currently serves the neighbouring property Braeburn, 4 Aultgrishan. It is proposed to upgrade the junction to provide a shared access and service layby which is compliant with current guideline standards. 1.4 The application is accompanied by a statutory design statement which makes reference to the scale and proportions of the house being considered to reflect that of existing properties in the area. 1.5 Variations: Revised plans have been received on four occasions: 07-03-2016 – revised site layout plan and house elevations. -

All Notices Gazette

ALL NOTICES GAZETTE CONTAINING ALL NOTICES PUBLISHED ONLINE BETWEEN 5 AND 7 JUNE 2015 PRINTED ON 8 JUNE 2015 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY | ESTABLISHED 1665 WWW.THEGAZETTE.CO.UK Contents State/2* Royal family/ Parliament & Assemblies/ Honours & Awards/ Church/ Environment & infrastructure/3* Health & medicine/ Other Notices/28* Money/ Companies/29* People/97* Terms & Conditions/134* * Containing all notices published online between 5 and 7 June 2015 STATE STATE Departments of State CROWN OFFICE 2344367THE QUEEN has been pleased by Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the Realm dated 2 June 2015 to appoint Alistair William Orchard MacDonald, Esquire, Q.C., to be a Justice of Her Majesty’s High Court. C I P Denyer (2344367) 2344364THE QUEEN has been pleased by Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the Realm dated 2 June 2015 to appoint: The Right Honourable David William Donald Cameron, The Right Honourable George Gideon Oliver Osborne, David Anthony Evennett, Esquire, John David Penrose, Esquire, Alun Hugh Cairns, Esquire, Melvyn John Stride, Esquire, George Hollingbery, Esquire and Charles Elphicke, Esquire, to be Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Treasury. C.I.P Denyer (2344364) Honours & awards State Awards THE ROYAL VICTORIAN ORDER CENTRAL2344362 CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD St. James’s Palace, London S.W.1. 5 June 2015 THE QUEEN has been graciously pleased to give orders for the following appointment to the Royal Victorian Order: KCVO To be a Knight Commander: His Royal Highness PRINCE HENRY OF WALES. (To be dated 4 June 2015.) (2344362) 2 | CONTAINING ALL NOTICES PUBLISHED ONLINE BETWEEN 5 AND 7 JUNE 2015 | ALL NOTICES GAZETTE ENVIRONMENT & INFRASTRUCTURE • Full Planning Permission (ref: K/2006/0164/F) granted 02nd December 2008 for 3 x wind turbines with maximum overall ENVIRONMENT & height of 100m, later amended to 3 x wind turbines with overall height of 110m, and granted permission on 12th November 2014 (ref: K/2012/0034/F).