Regulatory Reform in Rail Transport—The UK Experience Chris Nash*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rail Accident Report

Rail Accident Report Penetration and obstruction of a tunnel between Old Street and Essex Road stations, London 8 March 2013 Report 03/2014 February 2014 This investigation was carried out in accordance with: l the Railway Safety Directive 2004/49/EC; l the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003; and l the Railways (Accident Investigation and Reporting) Regulations 2005. © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This document/publication is also available at www.raib.gov.uk. Any enquiries about this publication should be sent to: RAIB Email: [email protected] The Wharf Telephone: 01332 253300 Stores Road Fax: 01332 253301 Derby UK Website: www.raib.gov.uk DE21 4BA This report is published by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, Department for Transport. Penetration and obstruction of a tunnel between Old Street and Essex Road stations, London 8 March 2013 Contents Summary 5 Introduction 6 Preface 6 Key definitions 6 The incident 7 Summary of the incident 7 Context 7 Events preceding the incident 9 Events following the incident 11 Consequences of the incident 11 The investigation 12 Sources of evidence 12 Key facts and analysis -

Strategic Rail Authority

Guidance on Complaints Handling Procedure Strategic Rail Authority February 2005 Contents Introduction 3 Principles 3 Accessibility and publicity 4 Simplicity of understanding and use 5 Speed of response 6 Confidentiality 7 Full and fair investigation 7 Effective response and appropriate redress 8 Monitoring, auditing and review 8 Interface with insurance claim publicity and procedures 9 Consultation 9 Annex A: Principles for dealing with ‘frivolous and vexatious’ complaints 10 Annex B: Principles for dealing with complaints involving two or more operators 12 2 Introduction 1. Passenger train and station operators are required to have complaint handling procedures, approved by the Rail Regulator (before 1 February 2001) or by the Authority (after 1 February 2001), in place from commencement of licensed operations. 2. Operators may propose whatever procedures best suit the needs and expectations of their customers and the requirements of their businesses. However, this guidance document sets out fundamental principles which the Authority will expect to see reflected in any complaint handling procedure submitted to it for approval and the way in which those principles should be incorporated into operators’ procedures. Whilst this guidance document imposes no absolute requirements upon licensed operators, the Strategic Rail Authority will, as far as possible, measure complaint handling procedures proposed by operators against the contents of this guidance. Principles 3. A complaint handling system should: • Be easily accessible and well -

The Uk's Privatisation Experiment

THE UK’S PRIVATISATION EXPERIMENT: THE P ASSAGE OF TIME PERMITS A SOBER ASSESSMENT DAVID PARKER CESIFO WORKING PAPER NO. 1126 CATEGORY 9: INDUSTRIAL ORGANISATION FEBRUARY 2004 PRESENTED AT CESIFO CONFERENCE ON PRIVATISATION EXPERIENCES IN THE EU NOVEMBER 2003 An electronic version of the paper may be downloaded • from the SSRN website: www.SSRN.com • from the CESifo website: www.CESifo.de CESifo Working Paper No. 1126 THE UK’S PRIVATISATION EXPERIMENT: THE PASSAGE OF TIME PERMITS A SOBER ASSESSMENT Abstract This chapter looks at the UK’s privatisation experiment, which began from the late 1970s. It considers the background to the UK’s privatisations, which industries were privatised and how, and summarises the results of studies of performance changes in privatised companies in the UK. It looks at the relative roles of competition, regulation and ownership changes in determining performance improvement. It concludes by looking at the wider lessons that might be learned from the UK’s privatisation experiment, including the importance of developing competitive markets and, in their absence, effective regulatory regimes. Keywords: UK, privatisation, competition regulation, lessons. JEL Classification: L33, H82, L51. David Parker Cranfield University School of Management Cranfield Bedfordshire MK43 0AL United Kingdom [email protected] Introduction The Labour Government of 1974-79 arranged the sale of some of the state’s shareholding in the petroleum company BP. However, this sale was dictated by budgetary pressures and did not reflect a belief within government that state industries should be privatised. Indeed, the same Labour Government took into state ownership two major industries, namely aerospace and shipbuilding. -

DIRECTIONS and GUIDANCE to the Strategic Rail Authority

DIRECTIONS AND GUIDANCE to the Strategic Rail Authority ESTABLISHMENT OF THE STRATEGIC RAIL AUTHORITY 1. The Strategic Rail Authority (“the Authority”) has been established under section 201(1) of the Transport Act 2000 (“the Act”) as a body corporate. PURPOSES OF THE STRATEGIC RAIL AUTHORITY 2.1. The Authority is to provide leadership for the rail industry and ensure that the industry works co-operatively towards common goals. This objective should underpin the whole range of the Authority’s activities. The Authority will set priorities for the successful operation and development of the railway. It will work with other industry parties to secure continuing private investment in the railway, and to deploy public funding to best effect. To this end, the Authority has been given a wide range of statutory powers and duties. 2.2. Section 205 of the Act sets out the Authority’s purposes as: • to promote the use of the railway network for the carriage of passengers and goods; • to secure the development of the railway network; and • to contribute to the development of an integrated system of transport for passengers and goods. 2.3. Section 207 of the Act requires the Authority to exercise its functions with a view to furthering its purposes and it must do so in accordance with any strategies that it has formulated with respect to them. In so doing the Authority must act in the way best calculated: • to protect the interests of users of railway services; • to contribute to the achievement of sustainable development; 1 • to promote efficiency and economy on the part of persons providing railway services; • to promote measures designed to facilitate passenger journeys involving more than one operator (including, in particular, arrangements for the issue and use of through tickets); • to impose on operators of railway services the minimum restrictions consistent with the performance of its functions; and • to enable providers of rail services to plan their businesses with a reasonable degree of assurance. -

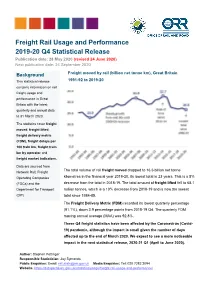

Freight Rail Usage and Performance 2019-20 Q4 Statistical Release Publication Date: 28 May 2020 (Revised 24 June 2020) Next Publication Date: 24 September 2020

Freight Rail Usage and Performance 2019-20 Q4 Statistical Release Publication date: 28 May 2020 (revised 24 June 2020) Next publication date: 24 September 2020 Freight moved by rail (billion net tonne km), Great Britain Background This statistical release 1991-92 to 2019-20 contains information on rail freight usage and performance in Great Britain with the latest quarterly and annual data to 31 March 2020. The statistics cover freight moved, freight lifted, freight delivery metric (FDM), freight delays per 100 train km, freight train km by operator and freight market indicators. Data are sourced from The total volume of rail dropped to 16.6 billion net tonne Network Rail, Freight freight moved Operating Companies kilometres in the financial year 2019-20, its lowest total in 23 years. This is a 5% (FOCs) and the decrease from the total in 2018-19. The total amount of freight lifted fell to 68.1 Department for Transport million tonnes, which is a 10% decrease from 2018-19 and is now the lowest (DfT). total since 1984-85. The Freight Delivery Metric (FDM) recorded its lowest quarterly percentage (91.1%), down 3.9 percentage points from 2018-19 Q4. The quarterly FDM moving annual average (MAA) was 92.8%. These Q4 freight statistics have been affected by the Coronavirus (Covid- 19) pandemic, although the impact is small given the number of days affected up to the end of March 2020. We expect to see a more noticeable impact in the next statistical release, 2020-21 Q1 (April to June 2020). Author: Stephen Pottinger Responsible Statistician: Jay Symonds Public Enquiries: Email: [email protected] Media Enquiries: Tel: 020 7282 2094 Website: https://dataportal.orr.gov.uk/statistics/usage/freight-rail-usage-and-performance/ 1. -

The Strategic Case for Hs2

THE STRATEGIC CASE FOR HS2 October 2013 THE STRATEGIC CASE FOR HS2 October 2013 High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. Department for Transport Great Minster House 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR Telephone: 0300 330 3000 Website: www.gov.uk/dft Department for Transport has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the Department’s website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact the Department. © Crown Copyright, 2013, except where otherwise stated. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v2.0. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. To order further copies contact: DfT Publications Tel: 0300 123 1102 Web: www.dft.gov.uk/orderingpublications Product code: DfT 014 Printed in Great Britain on paper containing at least 75% recycled fibre. -

Members and Parish/Neighbourhood Councils RAIL UPDATE

ITEM 1 TRANSPORT COMMITTEE NEWS 07 MARCH 2000 This report may be of interest to: All Members and Parish/Neighbourhood Councils RAIL UPDATE Accountable Officer: John Inman Author: Stephen Mortimer 1. Purpose 1.1 To advise the Committee of developments relating to Milton Keynes’ rail services. 2. Summary 2.1 West Coast Main Line Modernisation and Upgrade is now in the active planning stage. It will result in faster and more frequent train services between Milton Keynes Central and London, and between Milton Keynes Central and points north. Bletchley and Wolverton will also have improved services to London. 2.2 Funding for East-West Rail is now being sought from the Shadow Strategic Rail Authority (SSRA) for the western end of the line (Oxford-Bedford). Though the SSRA have permitted a bid only for a 60 m.p.h. single-track railway, excluding the Aylesbury branch and upgrade of the Marston Vale (Bedford-Bletchley) line, other Railtrack investment and possible developer contributions (yet to be investigated) may allow these elements to be included, as well as perhaps a 90 m.p.h. double- track railway. As this part of East-West Rail already exists, no form of planning permission is required; however, Transport and Works Act procedures are to be started to build the missing parts of the eastern end of the line. 2.3 New trains were introduced on the Marston Vale line, Autumn 1999. A study of the passenger accessibility of Marston Vale stations identified various desirable improvements, for which a contribution of £10,000 is required from this Council. -

Eighth Annual Market Monitoring Working Document March 2020

Eighth Annual Market Monitoring Working Document March 2020 List of contents List of country abbreviations and regulatory bodies .................................................. 6 List of figures ............................................................................................................ 7 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 9 2. Network characteristics of the railway market ........................................ 11 2.1. Total route length ..................................................................................................... 12 2.2. Electrified route length ............................................................................................. 12 2.3. High-speed route length ........................................................................................... 13 2.4. Main infrastructure manager’s share of route length .............................................. 14 2.5. Network usage intensity ........................................................................................... 15 3. Track access charges paid by railway undertakings for the Minimum Access Package .................................................................................................. 17 4. Railway undertakings and global rail traffic ............................................. 23 4.1. Railway undertakings ................................................................................................ 24 4.2. Total rail traffic ......................................................................................................... -

The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 2 Report

Responsibility for the regulation of health and safety on the railways was transferred from the Health and Safety Commission (HSC) and Health and Safety Executive (HSE) to the Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) on 1 April 2006. This document was originally produced by HSC/E but responsibility for the subject/work area in the document has now moved to ORR. If you would like any further information, please contact the ORR's Correspondence Section - [email protected] The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 2 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 2 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC © Crown copyright 2001 Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ First published 2001 ISBN 0 7176 2107 3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. 1 Front cover: Taken from a photograph supplied by Milepost 92 /2 ii Contents Chapters 1 Executive summary 3 2 The Inquiry 11 3 The rail industry and its regulation 19 4 The implications of privatisation 39 5 The management and culture of safety 59 6 Railway Group Standards 79 7 Safety cases, accreditation and licensing 85 8 Railtrack and Railway Safety 109 9 The safety regulator 123 10 A rail industry safety body 155 11 An accident investigation body -

Railways: 2004 White Paper

Railways: 2004 White Paper Standard Note: SN/BT/3142 Last updated: 31 March 2010 Author: Louise Butcher Section Business and Transport This note summarises the White Paper The Future of Rail published on 15 July 2004. The document and associated information can be found on the Department for Transport's archive. The then Secretary of State for Transport, Alistair Darling, announced a review of the railways in January 2004; this was followed by a report of the Transport Select Committee in April; and the Government’s conclusions and response to the Committee was published in a White Paper in July. The Secretary of State had ruled out renationalising the railways before the review took place and after consideration, he decided against radically changing the structure to a system of common ownership of the track and train. The White Paper identified weaknesses in the existing system for managing the railways and proposed changing the structure by: • Abolishing the Strategic Rail Authority (SRA) and moving its strategic functions and financial obligations to the Department for Transport; • Giving responsibility for operating the network and for its performance to Network Rail; • Reducing the number of passenger franchises and aligning them more closely with Network Rail's regional structure; • Increasing the role of the Scottish Executive, the Welsh Assembly and the London Mayor, in determining passenger services and where appropriate, infrastructure; and • Giving the Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) responsibility for safety, performance and cost. A number of these changes – notably the closure of the SRA, the transfer of safety regulation, and proposals relating to devolved decision-making – were legislated for in the Railways Act 2005. -

Appointment of Her Majesty's Chief

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Appointment of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary Third Report of Session 2012–13 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 26 June 2012 HC 183-II Published on 9 August 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £7.50 The Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Keith Vaz MP (Labour, Leicester East) (Chair) Nicola Blackwood MP (Conservative, Oxford West and Abingdon) James Clappison MP (Conservative, Hertsmere) Michael Ellis MP (Conservative, Northampton North) Lorraine Fullbrook MP (Conservative, South Ribble) Dr Julian Huppert MP (Liberal Democrat, Cambridge) Steve McCabe MP (Labour, Birmingham Selly Oak) Rt Hon Alun Michael MP (Labour & Co-operative, Cardiff South and Penarth) Bridget Phillipson MP (Labour, Houghton and Sunderland South) Mark Reckless MP (Conservative, Rochester and Strood) Mr David Winnick MP (Labour, Walsall North) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/homeaffairscom. Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are Tom Healey (Clerk), Richard Benwell (Second Clerk), Ruth Davis (Committee Specialist), Eleanor Scarnell (Committee Specialist), Andy Boyd (Senior Committee Assistant), John Graddon (Committee Support Officer) and Alex Paterson (Select Committee Media Officer). -

Competition Act 1998

Competition Act 1998 Decision of the Office of Rail Regulation* English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited Relating to a finding by the Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) of an infringement of the prohibition imposed by section 18 of the Competition Act 1998 (the Act) and Article 82 of the EC Treaty in respect of conduct by English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited. Introduction 1. This decision relates to conduct by English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited (EWS) in the carriage of coal by rail in Great Britain. 2. The case results from two complaints. 3. On 1 February 2001 Enron Coal Services Limited (ECSL)1 submitted a complaint to the Director of Fair Trading2. Jointly with ECSL, Freightliner Limited (Freightliner) also, within the same complaint, alleged an infringement of the Chapter II prohibition in respect of a locomotive supply agreement between EWS and General Motors Corporation of the United States (General Motors). Together these are referred to as the Complaint. The Complaint alleges: “[…] that English, Welsh and Scottish Railways Limited (‘EWS’), the dominant supplier of rail freight services in England, Wales and Scotland, has systematically and persistently acted to foreclose, deter or limit Enron Coal Services Limited’s (‘ECSL’) participation in the market for the supply of coal to UK industrial users, particularly in the power sector, to the serious detriment of competition in that market. The complaint concerns abusive conduct on the part of EWS as follows. • Discriminatory pricing as between purchasers of coal rail freight services so as to disadvantage ECSL. *Certain information has been excluded from this document in order to comply with the provisions of section 56 of the Competition Act 1998 (confidentiality and disclosure of information) and the general restrictions on disclosure contained at Part 9 of the Enterprise Act 2002.