Statism by Stealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Populist Backlash Against Europe : Why Only Alternative Economic and Social Policies Can Stop the Rise of Populism in Europe

This is a repository copy of The populist backlash against Europe : why only alternative economic and social policies can stop the rise of populism in Europe. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/142119/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Bugaric, B. (2020) The populist backlash against Europe : why only alternative economic and social policies can stop the rise of populism in Europe. In: Bignami, F., (ed.) EU Law in Populist Times : Crises and Prospects. Cambridge University Press , pp. 477-504. ISBN 9781108485081 https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108755641 © 2020 Francesca Bignami. This is an author-produced version of a chapter subsequently published in EU Law in Populist Times. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. See: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108755641. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Populist Backlash Against Europe: Why Only Alternative Economic and Social Policies Can Stop the Rise of Populism in Europe Bojan Bugarič1 I. -

Philosophical Statism and the Illusions of Citizenship Reflections on the Neutral State

1 Philosophical Statism and the Illusions of Citizenship Reflections on the Neutral State Frank van Dun ∗ Is the welfare state neutral to personal morality? 1 In today's welfare states one can find numerous life-styles existing side by side. These indicate a wide scope for 'personal mo- ralities' 2, but do not prove that the welfare state is 'neutral' to them. Welfare states interfere in more or less onerous ways with the business of (private) life with police checks, administrative controls and a vast arsenal of regulatory, penal and/or fiscal regimes. Some of the regulations may be more or less reasonable attempts to minimise the risk of one person inflicting irreparable damage on others or their property, but a great many are not. It is not too difficult to see the hand of special (economic, ideological, even sectarian) interests in the bulk of the rules and regulations on the books. 3 The state's non-neutrality is often an unintended outcome, but not always. Officials introduce new regulations with proud declarations of their intention to enforce particular 'moral choices', to treat one thing as a 'merit good' and another as an evil. They also justify intrusive policies with blatantly paternalistic arguments—remember their promise, or was it threat, to take care of us "from the cradle to the grave"—, with self-congratulatory references to an unspecified 'responsibility of the government'. There is no more direct negation of the role of private mo- rality than the claim that one discharges one's own responsibility by depriving others of the opportunity to exercise theirs. -

Reconciling Statism with Freedom: Turkey's Kurdish Opening

Reconciling Statism with Freedom Turkey’s Kurdish Opening Halil M. Karaveli SILK ROAD PAPER October 2010 Reconciling Statism with Freedom Turkey’s Kurdish Opening Halil M. Karaveli © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 1619 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20036 Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodav. 2, Stockholm-Nacka 13130, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Reconciling Statism with Freedom: Turkey’s Kurdish Opening” is a Silk Road Paper published by the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and the Silk Road Studies Program. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and ad- dresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of Johns Hopkins University and the Stockholm-based Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse commu- nity of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lec- tures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public dis- cussion regarding the region. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this study are those of the authors only, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Joint Center or its sponsors. -

Danny Kruger Selected As Conservative Parliamentary Candidate for Devizes

Press Release t (Press) 020 7984 8121 t (Broadcast) 020 7984 8180 f 020 7222 1135 Saturday 9 November 2019 Danny Kruger selected as Conservative Parliamentary candidate for Devizes A close aide of Prime Minister Boris Johnson has been selected as the Conservative Parliamentary candidate for Devizes. Danny Kruger was chosen at a selection meeting at the Corn Exchange in Devizes this afternoon (Saturday), which was attended by over 300 (CHECK) local Conservative members. Danny has been political secretary to the Prime Minister since July 2019 and has previously worked as chief speechwriter to David Cameron when he was Leader of the Opposition and an adviser to former Conservative Party leaders Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard. He helped to develop Mr Cameron’s ‘Big Society’ agenda and is keen to promote the same ethos in Devizes, empowering volunteers, businesses and community groups to tackle local issues and challenges. Danny is keen to boost local NHS services, support the police to tackle rural crime, ensure schools get their fair share of increased funding, push for greater infrastructure investment, enhance the rail and bus network and help businesses be more productive. He is a strong supporter of the Armed Forces and wants to ensure the relocation of service families to Wiltshire is a success for everyone. Danny supports Mr Johnson’s determination to get Brexit done as soon as possible and forge a positive new relationship with the EU. “I’m proud and excited to be selected as the Conservative Parliamentary candidate for Devizes and I’m looking forward to knocking on doors, meeting local people and addressing their concerns,” said Danny. -

The China Strategy America Needs DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, Mcqs, Magazines

Race and health: far from equal Afghanistan, a premature evacuation Remaking the British state Golf’s biggest hitters NOVEMBER 21ST–27TH 2020 The China strategy America needs DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Contents The Economist November 21st 2020 3 The world this week United States 6 A summary of political 23 To the bitter end and business news 24 Missile defence 25 Charles Koch Leaders 25 The State Department 9 China and America A new grand bargain 26 Midwestern corruption 27 Development v cemeteries 10 American politics The art of losing 27 Charters and covid-19 10 Afghanistan 28 Lexington Barack Leaving too soon Obama’s book 11 Sovereign debt A better way not to pay The Americas 29 Mexico and cannabis On the cover 14 Race and health Wanted: more data 30 Illegal fishing in Ecuador As president, Joe Biden should 16 Reforming Britain 31 Bello Peru’s chaotic aim to strike a grand bargain Remaking the state politics with America’s democratic allies: leader, page 9, and briefing, page 19. -

The Rise and Fall of Fascism

The Rise and Fall of Fascism Michael Mann, Professor of Sociology, University of California at Los Angeles. E-mail: [email protected] Fascism was probably the most important political ideology created during the 20th century. In th e inter -war period it dominated half of Europe and threatened to overwhelm the other half. It also influenced many countries across the Middle East, Asia, Latin America and South Africa. In Asia, for example, its influence was probably strongest on the Chinese Kuomintang, Japanese militarists and Hindu nationalists. My book Fascists (Cambridge University Press, 2004) is based on research on fascists where they were strongest, in six European countries -- Austria, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Romania and Spain. In the book I ask the question, why did fascism rise to such prominence? And I answer it looking at the men and women who became fascists: who were they, what did they believe in, and how did they act? There are two main schools of interpretation among scholars as to the rise of fascism. An idealist school has focused on fascists' beliefs and doctrines, emphasizing their nationalist values. Most recently, some of these scholars have termed fascism a form of “political religion”. 1 A more materialist school has focused on fascism’s supposed lower -middle class or middle class (petit bourgeois or bourgeois) base and the supposed way in which fascism was used to save capitalism when it was in difficulties. The debates between them constitute yet another replay of ongoing polemics between idealism and materialism in the social sciences. Both nationalism and class were important in fascism. -

The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 2 Report

Responsibility for the regulation of health and safety on the railways was transferred from the Health and Safety Commission (HSC) and Health and Safety Executive (HSE) to the Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) on 1 April 2006. This document was originally produced by HSC/E but responsibility for the subject/work area in the document has now moved to ORR. If you would like any further information, please contact the ORR's Correspondence Section - [email protected] The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 2 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 2 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC © Crown copyright 2001 Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ First published 2001 ISBN 0 7176 2107 3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. 1 Front cover: Taken from a photograph supplied by Milepost 92 /2 ii Contents Chapters 1 Executive summary 3 2 The Inquiry 11 3 The rail industry and its regulation 19 4 The implications of privatisation 39 5 The management and culture of safety 59 6 Railway Group Standards 79 7 Safety cases, accreditation and licensing 85 8 Railtrack and Railway Safety 109 9 The safety regulator 123 10 A rail industry safety body 155 11 An accident investigation body -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

The Immoral Equivalent of War

1 The Immoral Equivalent of War Deirdre Nansen McCloskey We are in a war, say all the presidents, the thoughtful and quasi-liberal presidents such as Emmanuel Macron in France and Moon Jae-in in Korea, as well as the thoughtless and quasi- fascist ones such as Donald Trump in the US and Viktor Orbán in Hungary. A terrible war. But the worst part is not the war itself against the disease and, as collateral damage, the crushing of the economy, wretched though they are. The worst part is the post-War likelihood of a triumphant statism, and then the fascism to which triumphant statism regularly gives rise. The disease is for 2020. The fascism is forever. The young historian Eliah Bures wrote six months ago a collective review in Foreign Affairs of books from left and right, books that all used prominently what he calls “the other F- word,” fascism. He notes that the word can be used foolishly, to mean “politics I don’t like.” Thus the “Anti-Fa,” that is, “Anti-Fascist,” movement of the loony left in the US. Bures is correct. But slipping into extremes of nationalism, socialism, racism, and the rest of the quicksand of the 1930s is not impossible. The 1930s, after all, happened. In the 1930s. Late in Bures’ essay, by way of a comforting conclusion from the apparent safety of November 2019, he pens a sentence that has acquired a terrifying salience: “Barring a crisis of capitalism and democratic representation on the scale of the 1920s and ’30s, there is no reason to expect today’s populism to revert to fascism.” Uh oh. -

Three Faces of Fascism Sheri Berman

B•• KS Sheri Berman is a visiting associate professor of political science at Barnard College, Columbia University, and the author of The Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Ideological Dynamics of the Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, forthcoming. Three Faces of Fascism Sheri Berman Fascists Michael Mann New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004 The Anatomy of Fascism Robert O. Paxton New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004 The Seduction of Unreason: The Intellectual Romance with Fascism from Nietzsche to Postmodernism Richard Wolin Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004 In recent decades, the term “fascism” has terpretations of fascism’s nature and histori- basically been stripped of all substantive cal significance, and their impressive books content. People on the left often apply the should interest academics and general read- “fascist” tag to describe any right-wing thug ers alike. Together they provide an excellent they don’t like, and their opposite numbers opportunity to assess what is and is not have reciprocated with coinages such as known about fascism, as well as the rele- “feminazi” and “econazi.” Academics have vance of the topic for contemporary political been less glib, but even they have fought life. In particular, we will see that while passionately over how to characterize and old-style fascism is defunct in its original even analyze the phenomenon. Almost 85 home—Europe—its spirit lives on in years since fascism’s appearance and almost another part of the world in the guise of 60 years since its demise, reams of books radical Islam. about it still appear regularly, their authors Robert Paxton’s The Anatomy of Fascism often disagreeing sharply with one another is the most comprehensive of the three. -

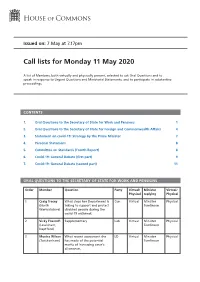

Call List for Mon 11 May 2020

Issued on: 7 May at 7.17pm Call lists for Monday 11 May 2020 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial Statements; and to participate in substantive proceedings. CONTENTS 1. Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions 1 2. Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs 4 3. Statement on covid-19: Strategy by the Prime Minister 7 4. Personal Statement 8 5. Committee on Standards (Fourth Report) 8 6. Covid-19: General Debate (first part) 9 7. Covid-19: General Debate (second part) 11 ORAL QUESTIONS TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister Virtual/ Physical replying Physical 1 Craig Tracey What steps her Department is Con Virtual Minister Physical (North taking to support and protect Tomlinson Warwickshire) disabled people during the covid-19 outbreak. 2 Vicky Foxcroft Supplementary Lab Virtual Minister Physical (Lewisham, Tomlinson Deptford) 3 Munira Wilson What recent assessment she LD Virtual Minister Physical (Twickenham) has made of the potential Tomlinson merits of increasing carer's allowance. 2 Call lists for Monday 11 May 2020 Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister Virtual/ Physical replying Physical 4 Karin Smyth What steps she has taken to Lab Virtual Minister Physical (Bristol South) help ensure prompt payment Tomlinson of access to work costs during the covid-19 outbreak. 5 Richard What recent assessment she Con Virtual Minister Virtual Graham has made of the effectiveness Quince (Gloucester) of the operation of universal credit. -

Constitutionalising Political Parties in Britain

Constitutionalising Political Parties in Britain Jongcheol Kim Department of Law London School of Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U117335 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U117335 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Constitutionalising Political Parties in Britain A Thesis Submitted to the University of London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jongcheol Kim (LL.B., LL.M.) Department of Law London School of Economics and Political Science 1998 S F 75S2 70/43Z Preface When almost five years ago I came to London to study British public law, I had no specific topic in mind that might form the basis for my Ph.D. course. I came with no particular background in British law, but having studied American constitutional law, the oldest written constitution in the modem world, I have decided it would be of considerable interest to further my understanding of modem constitutionalism by looking at the oldest example of an unwritten constitution. My knowledge of British public law was, then, extremely shallow and came almost exclusively from translating into Korean A.V.Dicey’s classic work,An Introduction to the Law o f the Constitution.