On Fraternity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danny Kruger Selected As Conservative Parliamentary Candidate for Devizes

Press Release t (Press) 020 7984 8121 t (Broadcast) 020 7984 8180 f 020 7222 1135 Saturday 9 November 2019 Danny Kruger selected as Conservative Parliamentary candidate for Devizes A close aide of Prime Minister Boris Johnson has been selected as the Conservative Parliamentary candidate for Devizes. Danny Kruger was chosen at a selection meeting at the Corn Exchange in Devizes this afternoon (Saturday), which was attended by over 300 (CHECK) local Conservative members. Danny has been political secretary to the Prime Minister since July 2019 and has previously worked as chief speechwriter to David Cameron when he was Leader of the Opposition and an adviser to former Conservative Party leaders Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard. He helped to develop Mr Cameron’s ‘Big Society’ agenda and is keen to promote the same ethos in Devizes, empowering volunteers, businesses and community groups to tackle local issues and challenges. Danny is keen to boost local NHS services, support the police to tackle rural crime, ensure schools get their fair share of increased funding, push for greater infrastructure investment, enhance the rail and bus network and help businesses be more productive. He is a strong supporter of the Armed Forces and wants to ensure the relocation of service families to Wiltshire is a success for everyone. Danny supports Mr Johnson’s determination to get Brexit done as soon as possible and forge a positive new relationship with the EU. “I’m proud and excited to be selected as the Conservative Parliamentary candidate for Devizes and I’m looking forward to knocking on doors, meeting local people and addressing their concerns,” said Danny. -

Z675928x Margaret Hodge Mp 06/10/2011 Z9080283 Lorely

Z675928X MARGARET HODGE MP 06/10/2011 Z9080283 LORELY BURT MP 08/10/2011 Z5702798 PAUL FARRELLY MP 09/10/2011 Z5651644 NORMAN LAMB 09/10/2011 Z236177X ROBERT HALFON MP 11/10/2011 Z2326282 MARCUS JONES MP 11/10/2011 Z2409343 CHARLOTTE LESLIE 12/10/2011 Z2415104 CATHERINE MCKINNELL 14/10/2011 Z2416602 STEPHEN MOSLEY 18/10/2011 Z5957328 JOAN RUDDOCK MP 18/10/2011 Z2375838 ROBIN WALKER MP 19/10/2011 Z1907445 ANNE MCINTOSH MP 20/10/2011 Z2408027 IAN LAVERY MP 21/10/2011 Z1951398 ROGER WILLIAMS 21/10/2011 Z7209413 ALISTAIR CARMICHAEL 24/10/2011 Z2423448 NIGEL MILLS MP 24/10/2011 Z2423360 BEN GUMMER MP 25/10/2011 Z2423633 MIKE WEATHERLEY MP 25/10/2011 Z5092044 GERAINT DAVIES MP 26/10/2011 Z2425526 KARL TURNER MP 27/10/2011 Z242877X DAVID MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2414680 JAMES MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2428399 PHILLIP LEE MP 31/10/2011 Z2429528 IAN MEARNS MP 31/10/2011 Z2329673 DR EILIDH WHITEFORD MP 31/10/2011 Z9252691 MADELEINE MOON MP 01/11/2011 Z2431014 GAVIN WILLIAMSON MP 01/11/2011 Z2414601 DAVID MOWAT MP 02/11/2011 Z2384782 CHRISTOPHER LESLIE MP 04/11/2011 Z7322798 ANDREW SLAUGHTER 05/11/2011 Z9265248 IAN AUSTIN MP 08/11/2011 Z2424608 AMBER RUDD MP 09/11/2011 Z241465X SIMON KIRBY MP 10/11/2011 Z2422243 PAUL MAYNARD MP 10/11/2011 Z2261940 TESSA MUNT MP 10/11/2011 Z5928278 VERNON RODNEY COAKER MP 11/11/2011 Z5402015 STEPHEN TIMMS MP 11/11/2011 Z1889879 BRIAN BINLEY MP 12/11/2011 Z5564713 ANDY BURNHAM MP 12/11/2011 Z4665783 EDWARD GARNIER QC MP 12/11/2011 Z907501X DANIEL KAWCZYNSKI MP 12/11/2011 Z728149X JOHN ROBERTSON MP 12/11/2011 Z5611939 CHRIS -

The China Strategy America Needs DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, Mcqs, Magazines

Race and health: far from equal Afghanistan, a premature evacuation Remaking the British state Golf’s biggest hitters NOVEMBER 21ST–27TH 2020 The China strategy America needs DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Contents The Economist November 21st 2020 3 The world this week United States 6 A summary of political 23 To the bitter end and business news 24 Missile defence 25 Charles Koch Leaders 25 The State Department 9 China and America A new grand bargain 26 Midwestern corruption 27 Development v cemeteries 10 American politics The art of losing 27 Charters and covid-19 10 Afghanistan 28 Lexington Barack Leaving too soon Obama’s book 11 Sovereign debt A better way not to pay The Americas 29 Mexico and cannabis On the cover 14 Race and health Wanted: more data 30 Illegal fishing in Ecuador As president, Joe Biden should 16 Reforming Britain 31 Bello Peru’s chaotic aim to strike a grand bargain Remaking the state politics with America’s democratic allies: leader, page 9, and briefing, page 19. -

Brexit: Initial Reflections

Brexit: initial reflections ANAND MENON AND JOHN-PAUL SALTER* At around four-thirty on the morning of 24 June 2016, the media began to announce that the British people had voted to leave the European Union. As the final results came in, it emerged that the pro-Brexit campaign had garnered 51.9 per cent of the votes cast and prevailed by a margin of 1,269,501 votes. For the first time in its history, a member state had voted to quit the EU. The outcome of the referendum reflected the confluence of several long- term and more contingent factors. In part, it represented the culmination of a longstanding tension in British politics between, on the one hand, London’s relative effectiveness in shaping European integration to match its own prefer- ences and, on the other, political diffidence when it came to trumpeting such success. This paradox, in turn, resulted from longstanding intraparty divisions over Britain’s relationship with the EU, which have hamstrung such attempts as there have been to make a positive case for British EU membership. The media found it more worthwhile to pour a stream of anti-EU invective into the resulting vacuum rather than critically engage with the issue, let alone highlight the benefits of membership. Consequently, public opinion remained lukewarm at best, treated to a diet of more or less combative and Eurosceptic political rhetoric, much of which disguised a far different reality. The result was also a consequence of the referendum campaign itself. The strategy pursued by Prime Minister David Cameron—of adopting a critical stance towards the EU, promising a referendum, and ultimately campaigning for continued membership—failed. -

Prosperity Without Growth?Transition the Prosperity to a Sustainable Economy 2009

Prosperity without growth? The transition to a sustainable economy to a sustainable The transition www.sd-commission.org.uk Prosperity England 2009 (Main office) 55 Whitehall London SW1A 2HH without 020 7270 8498 [email protected] Scotland growth? Osborne House 1 Osbourne Terrace, Haymarket Edinburgh EH12 5HG 0131 625 1880 [email protected] www.sd-commission.org.uk/scotland Wales Room 1, University of Wales, University Registry, King Edward VII Avenue, Cardiff, CF10 3NS Commission Development Sustainable 029 2037 6956 [email protected] www.sd-commission.org.uk/wales Northern Ireland Room E5 11, OFMDFM The transition to a Castle Buildings, Stormont Estate, Belfast BT4 3SR sustainable economy 028 9052 0196 [email protected] www.sd-commission.org.uk/northern_ireland Prosperity without growth? The transition to a sustainable economy Professor Tim Jackson Economics Commissioner Sustainable Development Commission Acknowledgements This report was written in my capacity as Economics Commissioner for the Sustainable Development Commission at the invitation of the Chair, Jonathon Porritt, who provided the initial inspiration, contributed extensively throughout the study and has been unreservedly supportive of my own work in this area for many years. For all these things, my profound thanks. The work has also inevitably drawn on my role as Director of the Research group on Lifestyles, Values and Environment (RESOLVE) at the University of Surrey, where I am lucky enough to work with a committed, enthusiastic and talented team of people carrying out research in areas relevant to this report. Their research is evident in the evidence base on which this report draws and I’m as grateful for their continuing intellectual support as I am for the financial support of the Economic and Social Research Council (Grant No: RES-152-25-1004) which keeps RESOLVE going. -

25 Haigron Ac

Cercles 25 (2012) !"#$#%&'()#*)#!"#&)+&,()-.".'/-#+/!'.'01)#2# #(34+./4)(5#*'"6-/(.'%(#).#&)4)*)(#+&/+/()(# # # # *"7'*#8"'6&/-# !"#$%&'#()*+%*,-%"# # ! "#! $%&'(#)*#*! +$+,-*#*! )$./#(*.0+.(#*! #0! 1%)($+,.*0.2)#*! 3%$/#(4#$0! 5%)(! 6.+4$%*0.2)#(! )$#! 7!3(.*#! 6#! ,+! (#5(8*#$0+0.%$! 5%,.0.2)#!9! 6+$*! ,#*! 68&%3(+0.#*!%33.6#$0+,#*:!;#!<%-+)&#=>$.!$?#*0!5+*!85+(4$8!5+(!3#!3%$*0+0:! @#3.!*?#A5(.&#B!#$0(#!+)0(#*B!5+(!)$#!*)*5.3.%$!4(+$6.**+$0#!C!,?84+(6!6#!,+! 3,+**#! 5%,.0.2)#! D4%)/#($#&#$0B! 5+(,#&#$0B! 5+(0.*EB! #A5(.&8#! 6+$*! ,#*! *%$6+4#*! 6?%5.$.%$B! 5+(! )$#! F+)**#! 6#! ,?+'*0#$0.%$! %)! 5+(! )$! /%0#! 5,)*! G,)30)+$0! #0! 5,)*! 83,+08:! ;#*! 3+)*#*! *)55%*8#*! *%$0! 6.GG)*#*B! &+.*! *#! 3(.*0+,,.*#$0!+)0%)(!6)!*#$0.&#$0!2)#!,#*!5+(0.*!5%,.0.2)#*B!#$!48$8(+,B!#0!,#*! 4%)/#($#&#$0*B!#$!5+(0.3),.#(B!$#!(#*5#30#$0!5+*!,+!/%,%$08!6#!,?8,#30%(+0!#0! 2)#!,#)(!+30.%$!$#!*#(0!5+*!#$!5(.%(.08!3#)A!2)?.,*!*%$0!3#$*8*!(#5(8*#$0#(:!@#! 2).! G+.0! 7!3(.*#!9! #*0! 6%$3! ,+! (#&.*#! #$! 3+)*#! 5+(! ,#*! 3.0%-#$*B! 6+$*! ,#*! 68&%3(+0.#*!6.0#*!(#5(8*#$0+0./#*B!6#!,+!,84.0.&.08!6#!,#)(*!(#5(8*#$0+$0*!D,#*! 8,)*E!C!,#*!(#5(8*#$0#(!D3?#*0=C=6.(#!C!5(#$6(#!6#*!683.*.%$*!#$!,#)(!$%&E:! "?)$#!&+$.H(#!48$8(+,#B!,+!$%0.%$!6#!7!3(.*#!9!*)55%*#!)$#!()50)(#!5+(! (+55%(0! C! )$! %(6(#! 80+',.! %)! .68+,:! "+$*! ,#! 6.*3%)(*! 5%,.0.2)#B! #,,#! 3%((#*5%$6! C! )$! 68(H4,#&#$0! +)2)#,! .,! G+)0! +55%(0#(! )$#! 7!*%,)0.%$!9! D,#! 5,)*! *%)/#$0! 6+$*! ,?)(4#$3#E! #0! *#*! 3+)*#*! *%$0! ,#! 5,)*! *%)/#$0! 5(8*#$08#*! 3%&&#! #A%4H$#*:! @#3.! *#! /8(.G.#! 5+(0.3),.H(#&#$0! -

Building the Big Society

Building the Big Society Defining the Big Society Delivering the Big Society Financing the Big Society Can big ideas succeed in politics? With Clive Barton, Roberta Blackman-Woods MP, Rob Brown, Sir Stephen Bubb, Patrick Butler, Chris Cummings, Michele Giddens, David Hutchison, Bernard Jenkin MP, Rt Hon Oliver Letwin MP, Jesse Norman MP, Ali Parsa, Michael Smyth CBE, Matthew Taylor and Andrew Wates Clifford Chance 10 Upper Bank Street London E14 5JJ Thursday 31 March 2011 Reform is an independent, non-party think tank whose mission is to set out a better way to deliver public services and economic prosperity. We believe that by reforming the public sector, increasing investment and extending choice, high quality services can be made available for everyone. Our vision is of a Britain with 21st Century healthcare, high standards in schools, a modern and efficient transport system, safe streets, and a free, dynamic and competitive economy. Reform 45 Great Peter Street London SW1P 3LT T 020 7799 6699 [email protected] www.reform.co.uk Building the Big Society / Reform Contents Building the Big Society Introduction 2 Pamphlet articles 5 Full transcript 14 www.reform.co.uk 1 Building the Big Society / Reform Introduction Nick Seddon, Deputy Director, Reform The Big Society is this Government’s Big “lacking a cutting edge” and “has no Sir Stephen Bubb spoke in favour of this Idea. Part philosophy, part practical teeth”. Others are outright hostile. They feature of the Government’s public service programme, it is the glue that holds see it as a cover for cuts. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

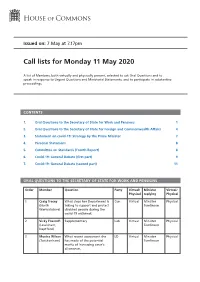

Call List for Mon 11 May 2020

Issued on: 7 May at 7.17pm Call lists for Monday 11 May 2020 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial Statements; and to participate in substantive proceedings. CONTENTS 1. Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions 1 2. Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs 4 3. Statement on covid-19: Strategy by the Prime Minister 7 4. Personal Statement 8 5. Committee on Standards (Fourth Report) 8 6. Covid-19: General Debate (first part) 9 7. Covid-19: General Debate (second part) 11 ORAL QUESTIONS TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister Virtual/ Physical replying Physical 1 Craig Tracey What steps her Department is Con Virtual Minister Physical (North taking to support and protect Tomlinson Warwickshire) disabled people during the covid-19 outbreak. 2 Vicky Foxcroft Supplementary Lab Virtual Minister Physical (Lewisham, Tomlinson Deptford) 3 Munira Wilson What recent assessment she LD Virtual Minister Physical (Twickenham) has made of the potential Tomlinson merits of increasing carer's allowance. 2 Call lists for Monday 11 May 2020 Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister Virtual/ Physical replying Physical 4 Karin Smyth What steps she has taken to Lab Virtual Minister Physical (Bristol South) help ensure prompt payment Tomlinson of access to work costs during the covid-19 outbreak. 5 Richard What recent assessment she Con Virtual Minister Virtual Graham has made of the effectiveness Quince (Gloucester) of the operation of universal credit. -

House of Commons Wednesday 10 September 2014 Votes and Proceedings

No. 36 305 House of Commons Wednesday 10 September 2014 Votes and Proceedings The House met at 11.30 am. PRAYERS. 1 Queen’s Speech (Answer to Address) The Vice-Chamberlain of the Household reported to the House, That Her Majesty, having been attended with its Address of 12 June, was pleased to receive the same very graciously and give the following Answer: I have received with great satisfaction the dutiful and loyal expression of your thanks for the speech with which I opened the present Session of Parliament. 2 Electoral Commission (Answer to Address) The Vice-Chamberlain of the Household reported to the House, That the Address of 15 July, praying that Her Majesty will re-appoint Lord Horam and David Howarth as Electoral Commissioners for the period ending on 30 September 2018, was presented to Her Majesty, who was graciously pleased to comply with the request. 3 Heywood and Middleton Ordered, That the Speaker do issue his Warrant to the Clerk of the Crown to make out a new Writ for the electing of a Member to serve in this present Parliament for the County Constituency of Heywood and Middleton in the room of James Dobbin, deceased.—(Ms Rosie Winterton.) 4 Questions to (1) the Minister for the Cabinet Office (2) the Prime Minister 5 Mobile Phones and Other Devices Capable of Connection to the Internet (Distribution of Sexually Explicit Images and Manufacturers’ Anti-Pornography Default Setting) Bill: Presentation (Standing Order No. 57) Geraint Davies, supported by Jessica Morden, Mrs Siân C. James, Chris Evans, Mr Mark Williams and Nia Griffith, presented a Bill to prohibit the distribution of sexually explicit images via the internet and text message without the consent of the subjects of the images; to provide that mobile phones and other devices capable of connection to the internet be set by manufacturers as a default to deny access to pornography; and for connected purposes. -

Britain's European Question and an In/Out Referendum

To be or not to be in Europe: is that the question? Britain’s European question and an in/out referendum TIM OLIVER* ‘It is time to settle this European question in British politics.’ David Cameron, 23 January 2013.1 Britain’s European question It came as no surprise to those who follow the issue of the European Union in British politics that David Cameron’s January 2013 speech on Europe excited a great deal of comment. The EU is among the most divisive issues in British politics. Cameron himself drew on this to justify his committing the Conservative Party, should it win the general election in 2015, to seek a renegotiated position for the UK within the EU which would then be put to the British people in an in/out referendum. Growing public frustrations at UK–EU relations were, he argued, the result of both a longstanding failure to consult the British people about their country’s place in the EU, and a changing EU that was undermining the current relationship between Britain and the Union. As a result, he argued, ‘the democratic consent for the EU in Britain is now wafer-thin’. Cameron’s speech was met with both criticism and praise from Eurosceptics and pro-Europeans alike.2 In a speech at Chatham House backing Cameron’s plan, the former Conservative prime minister Sir John Major best captured some of the hopes for a referendum: ‘The relationship with Europe has poisoned British politics for too long, distracted parliament from other issues and come close to destroying the Conservative Party. -

Dimeo and Henning Final.Pdf

This is an Accepted Manuscript of a chapter published by Taylor & Francis Group in Fincoeur B, Gleaves J & Ohl F (eds.) Doping in Cycling: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Ethics and Sport. Doping in Cycling: Interdisciplinary Perspectives: Routledge, pp. 177-188. https://www.routledge.com/Doping-in-Cycling-Interdisciplinary-Perspectives-1st- Edition/Fincoeur-Gleaves-Ohl/p/book/9781138477902 The Decline of Trust in British Sport since the London Olympics: Team Sky’s Fall from Grace Paul Dimeo and April Henning Abstract The success of Team Sky has been over-shadowed by a range of allegations and controversies, leaving significant doubts around their much-vaunted pro anti-doping stance. This chapter aims to contextualise these doubts within the wider frame of British sport, and more specifically the decline of trust. We trace the emergence of Team Sky from the National Lottery funded track team, arguing that the London Olympics was a pinnacle of medal-winning and public admiration. The turn towards professional road cycling was accompanied by new approaches to medicalisation. The Fancy Bears hack of WADA’s database, whistle-blower insights, Government inquiries, and media scrutiny have presented the public with sufficient evidence and critique to undermine the reputation of Team Sky’s management and riders. Other factors have contributed to the decline of trust, not least evidence of doping from the Russia investigations, the leaked IAAF blood files, the role of the IAAF senior managers, the conflict between WADA and the IOC over banning Russian athletes, and other related debates. We argue that the high-profile debate over the use of drugs in British professional cycling can be understood as symptomatic of a wider malaise affecting British sport, which in turn can be contextualised, explained, and seen as part of a broader shift in scepticism regarding political leaders and media organisations.