The Hindu-Arabic Numerals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbers - the Essence

Numbers - the essence A computer consists in essence of a sequence of electrical on/off switches. Big question: How do switches become a computer? ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 1 Friday, September 25, 2009 • A single switch is called a bit • A sequence of 8 bits is called a byte • Two or more bytes are often grouped to form word • Modern laptop/desktop standardly will have memory of 1 gigabyte = 1,000,000,000 bytes ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 2 Friday, September 25, 2009 Question: How do encode information with switches ? Answer: With numbers - binary numbers using only 0’s and 1’s where for each switch on position = 1 off position = 0 ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 3 Friday, September 25, 2009 • For a byte consisting of 8 bits there are a total of 28 = 256 ways to place 0’s and 1’s. Example 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 • For each grouping of 4 bits there are 24 = 16 ways to place 0’s and 1’s. • For a byte the first and second groupings of four bits can be represented by two hexadecimal digits • this will be made clear in following slides. ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 4 Friday, September 25, 2009 Bits & Bytes imply creation of data and computer analysis of data • storing data (reading) • processing data - arithmetic operations, evaluations & comparisons • output of results ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 5 Friday, September 25, 2009 Numeral systems A numeral system is any method of symbolically representing the counting numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, . -

On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet

- ON THE <)|{I<; IN <>F TIIK INDIAN BRAHMA ALPHABET GEORG BtfHLKi; SECOND REVISED EDITION OF INDIAN STUDIES, NO III. TOGETHER WITH TWO APPENDICES ON THE OKU; IN OF THE KHAROSTHI ALPHABET AND OF THK SO-CALLED LETTER-NUMERALS OF THE BRAHMI. WITH TIIKKK PLATES. STRASSBUKi-. K A K 1. I. 1 1M I: \ I I; 1898. I'lintccl liy Adolf Ilcil/.haiisi'ii, Vicniiii. Preface to the Second Edition. .As the few separate copies of the Indian Studies No. Ill, struck off in 1895, were sold very soon and rather numerous requests for additional ones were addressed both to me and to the bookseller of the Imperial Academy, Messrs. Carl Gerold's Sohn, I asked the Academy for permission to issue a second edition, which Mr. Karl J. Trlibner had consented to publish. My petition was readily granted. In addition Messrs, von Holder, the publishers of the Wiener Zeitschrift fur die Kunde des Morgenlandes, kindly allowed me to reprint my article on the origin of the Kharosthi, which had appeared in vol. IX of that Journal and is now given in Appendix I. To these two sections I have added, in Appendix II, a brief review of the arguments for Dr. Burnell's hypothesis, which derives the so-called letter- numerals or numerical symbols of the Brahma alphabet from the ancient Egyptian numeral signs, together with a third com- parative table, in order to include in this volume all those points, which require fuller discussion, and in order to make it a serviceable companion to the palaeography of the Grund- riss. -

From Al-Khwarizmi to Algorithm (71-74)

Olympiads in Informatics, 2017, Vol. 11, Special Issue, 71–74 71 © 2017 IOI, Vilnius University DOI: 10.15388/ioi.2017.special.11 From Al-Khwarizmi to Algorithm Bahman MEHRI Sharif University of Technology, Iran e-mail: [email protected] Mohammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (780–850), Latinized as Algoritmi, was a Persian mathematician, astronomer, and geographer during the Abbasid Caliphate, a scholar in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. In the 12th century, Latin translations of his work on the Indian numerals introduced the decimal number system to the Western world. Al-Khwarizmi’s The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing resented the first systematic solu- tion of linear and quadratic equations in Arabic. He is often considered one of the fathers of algebra. Some words reflect the importance of al-Khwarizmi’s contributions to mathematics. “Algebra” (Fig. 1) is derived from al-jabr, one of the two operations he used to solve quadratic equations. Algorism and algorithm stem from Algoritmi, the Latin form of his name. Fig. 1. A page from al-Khwarizmi “Algebra”. 72 B. Mehri Few details of al-Khwarizmi’s life are known with certainty. He was born in a Per- sian family and Ibn al-Nadim gives his birthplace as Khwarazm in Greater Khorasan. Ibn al-Nadim’s Kitāb al-Fihrist includes a short biography on al-Khwarizmi together with a list of the books he wrote. Al-Khwārizmī accomplished most of his work in the period between 813 and 833 at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. Al-Khwarizmi contributions to mathematics, geography, astronomy, and cartogra- phy established the basis for innovation in algebra and trigonometry. -

Texts in Transit in the Medieval Mediterranean

Texts in Transit in the medieval mediterranean Edited by Y. Tzvi Langermann and Robert G. Morrison Texts in Transit in the Medieval Mediterranean Texts in Transit in the Medieval Mediterranean Edited by Y. Tzvi Langermann and Robert G. Morrison Th e Pennsylvania State University Press University Park, Pennsylvania This book has been funded in part by the Minerva Center for the Humanities at Tel Aviv University and the Bowdoin College Faculty Development Committee. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Langermann, Y. Tzvi, editor. | Morrison, Robert G., 1969– , editor. Title: Texts in transit in the medieval Mediterranean / edited by Y. Tzvi Langermann and Robert G. Morrison. Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “A collection of essays using historical and philological approaches to study the transit of texts in the Mediterranean basin in the medieval period. Examines the nature of texts themselves and how they travel, and reveals the details behind the transit of texts across cultures, languages, and epochs”— Provided by Publisher. Identifiers: lccn 2016012461 | isbn 9780271071091 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Transmission of texts— Mediterranean Region— History— To 1500. | Manuscripts, Medieval— Mediterranean Region. | Civilization, Medieval. Classification: lcc z106.5.m43 t49 2016 | ddc 091 / .0937—dc23 lc record available at https:// lccn .loc .gov /2016012461 Copyright © 2016 The Pennsylvania State University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 16802–1003 The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses. -

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

AL-KINDI 'Philosopher of the Arabs' Abū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb Ibn Isḥāq Al

AL-KINDI ‘Philosopher of the Arabs’ – from the keyboard of Ghurayb Abū Yūsuf Ya ʿqūb ibn Is ḥāq Al-Kindī , an Arab aristocrat from the tribe of Kindah, was born in Basrah ca. 800 CE and passed away in Baghdad around 870 (or ca. 196–256 AH ). This remarkable polymath promoted the collection of ancient scientific knowledge and its translation into Arabic. Al-Kindi worked most of his life in the capital Baghdad, where he benefitted from the patronage of the powerful ʿAbb āssid caliphs al- Ma’mūn (rg. 813–833), al-Muʿta ṣim (rg. 833–842), and al-Wāthiq (rg. 842–847) who were keenly interested in harmonizing the legacy of Hellenic sciences with Islamic revelation. Caliph al-Ma’mūn had expanded the palace library into the major intellectual institution BAYT al-ḤIKMAH (‘Wisdom House ’) where Arabic translations from Pahlavi, Syriac, Greek and Sanskrit were made by teams of scholars. Al-Kindi worked among them, and he became the tutor of Prince A ḥmad, son of the caliph al-Mu ʿtasim to whom al-Kindi dedicated his famous work On First Philosophy . Al-Kindi was a pioneer in chemistry, physics, psycho–somatic therapeutics, geometry, optics, music theory, as well as philosophy of science. His significant mathematical writings greatly facilitated the diffusion of the Indian numerals into S.W. Asia & N. Africa (today called ‘Arabic numerals’ ). A distinctive feature of his work was the conscious application of mathematics and quantification, and his invention of specific laboratory apparatus to implement experiments. Al-Kindi invented a mathematical scale to quantify the strength of a drug; as well as a system linked to phases of the Moon permitting a doctor to determine in advance the most critical days of a patient’s illness; while he provided the first scientific diagnosis and treatment for epilepsy, and developed psycho-cognitive techniques to combat depression. -

The "Greatest European Mathematician of the Middle Ages"

Who was Fibonacci? The "greatest European mathematician of the middle ages", his full name was Leonardo of Pisa, or Leonardo Pisano in Italian since he was born in Pisa (Italy), the city with the famous Leaning Tower, about 1175 AD. Pisa was an important commercial town in its day and had links with many Mediterranean ports. Leonardo's father, Guglielmo Bonacci, was a kind of customs officer in the North African town of Bugia now called Bougie where wax candles were exported to France. They are still called "bougies" in French, but the town is a ruin today says D E Smith (see below). So Leonardo grew up with a North African education under the Moors and later travelled extensively around the Mediterranean coast. He would have met with many merchants and learned of their systems of doing arithmetic. He soon realised the many advantages of the "Hindu-Arabic" system over all the others. D E Smith points out that another famous Italian - St Francis of Assisi (a nearby Italian town) - was also alive at the same time as Fibonacci: St Francis was born about 1182 (after Fibonacci's around 1175) and died in 1226 (before Fibonacci's death commonly assumed to be around 1250). By the way, don't confuse Leonardo of Pisa with Leonardo da Vinci! Vinci was just a few miles from Pisa on the way to Florence, but Leonardo da Vinci was born in Vinci in 1452, about 200 years after the death of Leonardo of Pisa (Fibonacci). His names Fibonacci Leonardo of Pisa is now known as Fibonacci [pronounced fib-on-arch-ee] short for filius Bonacci. -

On the Use of Coptic Numerals in Egypt in the 16 Th Century

ON THE USE OF COPTIC NUMERALS IN EGYPT IN THE 16 TH CENTURY Mutsuo KAWATOKO* I. Introduction According to the researches, it is assumed that the culture of the early Islamic period in Egypt was very similar to the contemporary Coptic (Qibti)/ Byzantine (Rumi) culture. This is most evident in their language, especially in writing. It was mainly Greek and Coptic which adopted the letters deriving from Greek and Demotic. Thus, it was normal in those days for the official documents to be written in Greek, and, the others written in Coptic.(1) Gold, silver and copper coins were also minted imitating Byzantine Solidus (gold coin) and Follis (copper coin) and Sassanian Drahm (silver coin), and they were sometimes decorated with the representation of the religious legends, such as "Allahu", engraved in a blank space. In spite of such situation, around A. H. 79 (698), Caliph 'Abd al-Malik b. Marwan implemented the coinage reformation to promote Arabisation of coins, and in A. H. 87 (706), 'Abd Allahi b. 'Abd al-Malik, the governor- general of Egypt, pursued Arabisation of official documentation under a decree by Caliph Walid b. 'Abd al-Malik.(2) As a result, the Arabic letters came into the immediate use for the coin inscriptions and gradually for the official documents. However, when the figures were involved, the Greek or the Coptic numerals were used together with the Arabic letters.(3) The Abjad Arabic numerals were also created by assigning the numerical values to the Arabic alphabetic (abjad) letters just like the Greek numerals, but they did not spread very much.(4) It was in the latter half of the 8th century that the Indian numerals, generally regarded as the forerunners of the Arabic numerals, were introduced to the Islamic world. -

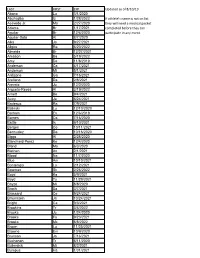

LAST FIRST EXP Updated As of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If Athlete's Name Is Not on List Acevedo Jr

LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If athlete's name is not on list Acevedo Jr. Ma 2/27/2020 they will need a medical packet Adams Br 1/17/2021 completed before they can Aguilar Br 12/6/2020 participate in any event. Aguilar-Soto Al 8/7/2020 Alka Ja 9/27/2021 Allgire Ra 6/20/2022 Almeida Br 12/27/2021 Amason Ba 5/19/2022 Amy De 11/8/2019 Anderson Ca 4/17/2021 Anderson Mi 5/1/2021 Ardizone Ga 7/16/2021 Arellano Da 2/8/2021 Arevalo Ju 12/2/2020 Argueta-Reyes Al 3/19/2022 Arnett Be 9/4/2021 Autry Ja 6/24/2021 Badeaux Ra 7/9/2021 Balinski Lu 12/10/2020 Barham Ev 12/6/2019 Barnes Ca 7/16/2020 Battle Is 9/10/2021 Bergen Co 10/11/2021 Bermudez Da 10/16/2020 Biggs Al 2/28/2020 Blanchard-Perez Ke 12/4/2020 Bland Ma 6/3/2020 Blethen An 2/1/2021 Blood Na 11/7/2020 Blue Am 10/10/2021 Bontempo Lo 2/12/2021 Bowman Sk 2/26/2022 Boyd Ka 5/9/2021 Boyd Ty 11/29/2021 Boyzo Mi 8/8/2020 Brach Sa 3/7/2021 Brassard Ce 9/24/2021 Braunstein Ja 10/24/2021 Bright Ca 9/3/2021 Brookins Tr 3/4/2022 Brooks Ju 1/24/2020 Brooks Fa 9/23/2021 Brooks Mc 8/8/2022 Brown Lu 11/25/2021 Browne Em 10/9/2020 Brunson Jo 7/16/2021 Buchanan Tr 6/11/2020 Bullerdick Mi 8/2/2021 Bumpus Ha 1/31/2021 LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Burch Co 11/7/2020 Burch Ma 9/9/2021 Butler Ga 5/14/2022 Byers Je 6/14/2021 Cain Me 6/20/2021 Cao Tr 11/19/2020 Carlson Be 5/29/2021 Cerda Da 3/9/2021 Ceruto Ri 2/14/2022 Chang Ia 2/19/2021 Channapati Di 10/31/2021 Chao Et 8/20/2021 Chase Em 8/26/2020 Chavez Fr 6/13/2020 Chavez Vi 11/14/2021 Chidambaram Ga 10/13/2019 -

Kharosthi Manuscripts: a Window on Gandharan Buddhism*

KHAROSTHI MANUSCRIPTS: A WINDOW ON GANDHARAN BUDDHISM* Andrew GLASS INTRODUCTION In the present article I offer a sketch of Gandharan Buddhism in the centuries around the turn of the common era by looking at various kinds of evidence which speak to us across the centuries. In doing so I hope to shed a little light on an important stage in the transmission of Buddhism as it spread from India, through Gandhara and Central Asia to China, Korea, and ultimately Japan. In particular, I will focus on the several collections of Kharo~thi manuscripts most of which are quite new to scholarship, the vast majority of these having been discovered only in the past ten years. I will also take a detailed look at the contents of one of these manuscripts in order to illustrate connections with other text collections in Pali and Chinese. Gandharan Buddhism is itself a large topic, which cannot be adequately described within the scope of the present article. I will therefore confine my observations to the period in which the Kharo~thi script was used as a literary medium, that is, from the time of Asoka in the middle of the third century B.C. until about the third century A.D., which I refer to as the Kharo~thi Period. In addition to looking at the new manuscript materials, other forms of evidence such as inscriptions, art and architecture will be touched upon, as they provide many complementary insights into the Buddhist culture of Gandhara. The travel accounts of the Chinese pilgrims * This article is based on a paper presented at Nagoya University on April 22nd 2004. -

2020 Language Need and Interpreter Use Study, As Required Under Chair, Executive and Planning Committee Government Code Section 68563 HON

JUDICIAL COUNCIL OF CALIFORNIA 455 Golden Gate Avenue May 15, 2020 San Francisco, CA 94102-3688 Tel 415-865-4200 TDD 415-865-4272 Fax 415-865-4205 www.courts.ca.gov Hon. Gavin Newsom Governor of California HON. TANI G. CANTIL- SAKAUYE State Capitol, First Floor Chief Justice of California Chair of the Judicial Council Sacramento, California 95814 HON. MARSHA G. SLOUGH Re: 2020 Language Need and Interpreter Use Study, as required under Chair, Executive and Planning Committee Government Code section 68563 HON. DAVID M. RUBIN Chair, Judicial Branch Budget Committee Chair, Litigation Management Committee Dear Governor Newsom: HON. MARLA O. ANDERSON Attached is the Judicial Council report required under Government Code Chair, Legislation Committee section 68563, which requires the Judicial Council to conduct a study HON. HARRY E. HULL, JR. every five years on language need and interpreter use in the California Chair, Rules Committee trial courts. HON. KYLE S. BRODIE Chair, Technology Committee The study was conducted by the Judicial Council’s Language Access Hon. Richard Bloom Services and covers the period from fiscal years 2014–15 through 2017–18. Hon. C. Todd Bottke Hon. Stacy Boulware Eurie Hon. Ming W. Chin If you have any questions related to this report, please contact Mr. Douglas Hon. Jonathan B. Conklin Hon. Samuel K. Feng Denton, Principal Manager, Language Access Services, at 415-865-7870 or Hon. Brad R. Hill Ms. Rachel W. Hill [email protected]. Hon. Harold W. Hopp Hon. Hannah-Beth Jackson Mr. Patrick M. Kelly Sincerely, Hon. Dalila C. Lyons Ms. Gretchen Nelson Mr. -

RELG 357D1 Sanskrit 2, Fall 2020 Syllabus

RELG 357D1: Sanskrit 2 Fall 2020 McGill University School of Religious Studies Tuesdays & Thursdays, 10:05 – 11:25 am Instructor: Hamsa Stainton Email: [email protected] Office hours: by appointment via phone or Zoom Note: Due to COVID-19, this course will be offered remotely via synchronous Zoom class meetings at the scheduled time. If students have any concerns about accessibility or equity please do not hesitate to contact me directly. Overview This is a Sanskrit reading course in which intermediate Sanskrit students will prepare translations of Sanskrit texts and present them in class. While the course will review Sanskrit grammar when necessary, it presumes students have already completed an introduction to Sanskrit grammar. Readings: All readings will be made available on myCourses. If you ever have any issues accessing the readings, or there are problems with a PDF, please let me know immediately. You may also wish to purchase or borrow a hard copy of Charles Lanman’s A Sanskrit Reader (1884) for ease of reference, but the ebook will be on myCourses. The exact reading on a given day will depend on how far we progressed in the previous class. For the first half of the course, we will be reading selections from the Lanman’s Sanskrit Reader, and in the second half of the course we will read from the Bhagavadgītā. Assessment and grading: Attendance: 20% Class participation based on prepared translations: 20% Test #1: 25% Test #2: 35% For attendance and class participation, students are expected to have prepared translations of the relevant Sanskrit text.