Henry James and the Well-Made Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theater Matters: Female Theatricality in Hawthorne, Alcott, Brontë, and James

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 Theater Matters: Female Theatricality in Hawthorne, Alcott, Brontë, and James Keiko Miyajima Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1059 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Theater Matters: Female Theatricality in Hawthorne, Alcott, Brontë, and James by Keiko Miyajima A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 Copyright @ 2015 Keiko Miyajima ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard Kaye ___________________ ________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Mario DiGangi ___________________ ________________________ Date Executive Officer David Reynolds Talia Schaffer Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Theater Matters: Female Theatricality in Hawthorne, Alcott, Brontë, and James By Keiko Miyajima Advisor: Professor Richard Kaye This dissertation examines the ways the novelists on both sides of the Atlantic use the figure of the theatrical woman to advance claims about the nature and role of women. Theater is a deeply paradoxical art form: Seen at once as socially constitutive and promoting mass conformity, it is also criticized as denaturalizing, decentering, etiolating, queering, feminizing. -

The World Beautiful in Books TO

THE WORLD BEAUTIFUL IN BOOKS BY LILIAN WHITING Author of " The World Beautiful," in three volumes, First, Second, " " and Third Series ; After Her Death," From Dreamland Sent," " Kate Field, a Record," " Study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning," etc. If the crowns of the world were laid at my feet in exchange for my love of reading, 1 would spurn them all. — F^nblon BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY ^901 PL Copyright, 1901, By Little, Brown, and Company. All rights reserved. I\17^ I S ^ November, 1901 UNIVERSITY PRESS JOHN WILSON AND SON • CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A. Lilian SMIjttins'fii glMoriiB The World Beautiful. First Series The World Beautiful. Second Series The World Beautiful. Third Series After her Death. The Story of a Summer From Dreamland Sent, and Other Poems A Studv of Elizabeth Barrett Browning The Spiritual Significance Kate Field: a Record The World Beautiful in Books TO One whose eye may fall upon these pages; whose presence in tlie world of thought and achievement enriches life ; whose genius and greatness of spirit inspire my every day with renewed energy and faith, — this quest for " The World Beautiful" in literature is inscribed by LILIAN WHITING. " The consecration and the poeVs dream" CONTENTS. BOOK I. p,,. As Food for Life 13 BOOK II. Opening Golden Doors 79 BOOK III. The Rose of Morning 137 BOOK IV. The Chariot of the Soul 227 BOOK V. The Witness of the Dawn 289 INDEX 395 ; TO THE READER. " Great the Master And sweet the Magic Moving to melody- Floated the Gleam." |0 the writer whose work has been en- riched by selection and quotation from " the best that is known and thought in* the world," it is a special pleasure to return the grateful acknowledgments due to the publishers of the choice literature over whose Elysian fields he has ranged. -

The Early Feminists' Struggle Against Patriarchy and Its Impetus to The

The early feminists’ struggle against patriarchy and its impetus to the nineteenth century american women’s rights movement in henry james’s the bostonians SKRIPSI Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For The Sarjana Degree in English Department By: Dessy Nuraini Anggariningsih NIM. C.0397025 FACULTY OF LETTERS AND FINE ARTS SEBELAS MARET UNIVERSITY SURAKARTA 2003 1 APPROVAL Approved to be examined before The Board of Examiners Faculty of Letters and Fine Arts Sebelas Maret University Thesis Consultant : 1. Dra. Endang Sri Astuti, MS ( ) First Consultant NIP. 130 902 533 2. Dra. Rara Sugiarti, M. Tourism ( ) Second Consultant NIP. 131 918 127 2 Approved by the Board of Examiners Faculty of Letters and Fine Arts Sebelas Maret Universuty On March 27th, 2003 The Board of Examiners: 1. Dra. Hj. Tri Retno Pudyastuti, M.Hum ( ) Chairman NIP. 131 472 639 2. Dra. Zita Rarastesa, MA ( ) Secretary NIP.132 206 593 3. Dra. Endang Sri Astuti, MS ( ) First Examiner NIP.130 902 533 4. Dra. Rara Sugiarti, M.Tourism ( ) Second Examiner NIP 131 918 127 Dean Faculty of Letters and Fine Arts Sebelas Maret University Dr. Maryono Dwi Rahardjo, SU NIP. 130 675 176 3 MOTTO “Verily, along with every hardship is relief. So, when you have finished your occupation, devote yourself for Allah’s worship. And to your Lord Alone tirn all your intention and hopes.” (Surat Al Insyoroh : 6 –7) A thousand miles begins at zero … 4 DEDICATION To my beloved Ibu’ and Bapak 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENT Alhamdulillaahirabbil ‘aalamiin. Nothing else can be uttered after long exhausting struggle have been done to complete this thesis. -

The Tragic Muse, by Henry James 1

The Tragic Muse, by Henry James 1 The Tragic Muse, by Henry James The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Tragic Muse, by Henry James This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Tragic Muse Author: Henry James Release Date: December 10, 2006 [eBook #20085] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 The Tragic Muse, by Henry James 2 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TRAGIC MUSE*** E-text prepared by Chuck Greif, R. Cedron, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team Europe (http://dp.rastko.net/) THE TRAGIC MUSE by HENRY JAMES MacMillan and Co., Limited St. Martin's Street, London 1921 PREFACE I profess a certain vagueness of remembrance in respect to the origin and growth of The Tragic Muse, which appeared in the Atlantic Monthly again, beginning January 1889 and running on, inordinately, several months beyond its proper twelve. If it be ever of interest and profit to put one's finger on the productive germ of a work of art, and if in fact a lucid account of any such work involves that prime identification, I can but look on the present fiction as a poor fatherless and motherless, a sort of unregistered and unacknowledged birth. I fail to recover my precious first moment of consciousness of the idea to which it was to give form; to recognise in it--as I like to do in general--the effect of some particular sharp impression or concussion. -

MISALLIANCE : Know-The-Show Guide

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey MISALLIANCE: Know-the-Show Guide Misalliance by George Bernard Shaw Know-the-Show Audience Guide researched and written by the Education Department of The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey Artwork: Scott McKowen The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey MISALLIANCE: Know-the-Show Guide In This Guide – MISALLIANCE: From the Director ............................................................................................. 2 – About George Bernard Shaw ..................................................................................................... 3 – MISALLIANCE: A Short Synopsis ............................................................................................... 4 – What is a Shavian Play? ............................................................................................................ 5 – Who’s Who in MISALLIANCE? .................................................................................................. 6 – Shaw on — .............................................................................................................................. 7 – Commentary and Criticism ....................................................................................................... 8 – In This Production .................................................................................................................... 9 – Explore Online ...................................................................................................................... 10 – Shaw: Selected -

A Novel, by Henry James. Author of "The Awkward Age," "Daisy Miller," "An International Episode," Etc

LIU Post, Special Collections Brookville, NY 11548 Henry James Book Collection Holdings List The Ambassadors ; a novel, by Henry James. Author of "The Awkward Age," "Daisy Miller," "An International Episode," etc. New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1903. First American edition. Light blue boards with dark blue diagonal-fine-ribbed stiff fabric-paper dust jacket, lettered and ruled in gilt. - A58b The American, by Henry James, Jr. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, late Ticknor and Fields, and Fields, Osgood & Company, 1877. First edition, third variant binding - in dark green cloth. Facing title page, advertisement of "Mr. James' Writings." - A4a The American, by Henry James, Jr. London: Ward, Lock & Co. [1877]. 1st English edition [unauthorized]. Publisher's advertisements before half- title page and on its verso. Advertisements on verso of title page. 15 pp of advertisements after the text and on back cover. Pictorial front cover missing. - A4b The American, by Henry James, Jr. London: Macmillan and Co., 1879. 2nd English edition (authorized). 1250 copies published. Dark blue cloth with decorative embossed bands in gilt and black across from cover. Variant green end- papers. On verso of title page: "Charles Dickens and Evans, Crystal Palace Press." Advertisements after text, 2 pp. -A4c The American Scene, by Henry James. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907. 1st edition. 1, 500 copies published. Second binding of red cross-grain cloth. " This is a remainder binding for 700 copies reported by the publisher as disposed of in 1913." Advertisements after text, 6 pp. - A63a The American Scene, by Henry James. New York and London: Harper &Brothers Publishers, 1907. -

Bernard Shaw: Profiling His Own ‘New Women’ in ‘Plays

© April 2021| IJIRT | Volume 7 Issue 11 | ISSN: 2349-6002 Bernard Shaw: Profiling his own ‘New Women’ in ‘Plays Pleasant’ and ‘Plays Unpleasant’ Shakuntala Mukherjee Department of English Literature, AMITY University Kolkata, Hooghly, India Abstract - Shaw was successful to shake men’s beliefs to lecture on Ibsen. Shaw was already familiar with the the foundation in all branches of life- be it science, Norwegian dramatist, having seen the London philosophy, economics, theology, drama, music, art, performance of ‘A Doll’s House’. The lecture became novel, politics, criticism, health, education, and what not. ‘The Quintessence of Ibsenism’. Shaw’s brilliant and George Bernard Shaw, who was regarded as a writer promising answers formed the contents of the without a moral purpose at the beginning of his career in literary circles, is today looked upon as a profound Saturday Review. It turned ‘Shaw’s attention to the thinker who saw the truth and revealed it through art. drama as a means of expression on the ideas crowding The brilliance of his dramatic technique and philosophy his mind’. His plays were the truth of life. Shaw’s aim is aptly illuminated by his unconventional art and as a dramatist was to understand everything around dramatic technique. him and through his plays he tried to convey what he Shaw through his drama brought things like realism and understood. He made efforts to enable the public to idealism, individualism and socialism, together. The understand his vision. Regarding this aspect of Shaw; ‘New Woman’ introduced by Shaw; was treated with Purdom writes: contempt or fear as it discussed on the age-old ‘He wrote plays to delight his audiences and to change assumptions on how a man or woman should be. -

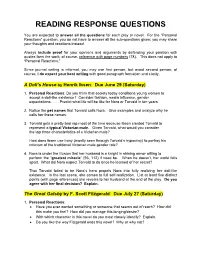

Reading Response Questions

READING RESPONSE QUESTIONS You are expected to answer all the questions for each play or novel. For the “Personal Reactions” question, you do not have to answer all the sub-questions given; you may share your thoughts and reactions instead. Always include proof for your opinions and arguments by defending your position with quotes form the work; of course, reference with page numbers (78). This does not apply to “Personal Reactions.” Since journal writing is informal, you may use first person, but avoid second person; of course, I do expect your best writing with good paragraph formation and clarity. A Doll’s House by Henrik IBsen: Due June 29 (Saturday) 1. Personal Reactions: Do you think that society today conditions young women to accept a doll-like existence? Consider fashion, media influence, gender expectations . Predict what life will be like for Nora or Torvald in ten years. 2. Notice the pet names that Torvald calls Nora. Give examples and analyze why he calls her these names. 3. Torvald gets a pretty bad rap most of the time because Ibsen created Torvald to represent a typical Victorian male. Given Torvald, what would you consider the top three characteristics of a Victorian male? How does Ibsen use irony (mostly seen through Torvald’s hypocrisy) to portray his criticism of the traditional Victorian male gender role? 4. Nora is under the illusion that her husband is a knight in shining armor willing to perform the “greatest miracle” (93, 112) if need be. When he doesn’t, her world falls apart. What did Nora expect Torvald to do once he learned of her secret? That Torvald failed to be Nora’s hero propels Nora into fully realizing her doll-like existence. -

Henry James , Edited by Adrian Poole Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01143-4 — The Princess Casamassima Henry James , Edited by Adrian Poole Frontmatter More Information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01143-4 — The Princess Casamassima Henry James , Edited by Adrian Poole Frontmatter More Information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01143-4 — The Princess Casamassima Henry James , Edited by Adrian Poole Frontmatter More Information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES general editors Michael Anesko, Pennsylvania State University Tamara L. Follini, University of Cambridge Philip Horne, University College London Adrian Poole, University of Cambridge advisory board Martha Banta, University of California, Los Angeles Ian F. A. Bell, Keele University Gert Buelens, Universiteit Gent Susan M. Grifn, University of Louisville Julie Rivkin, Connecticut College John Carlos Rowe, University of Southern California Ruth Bernard Yeazell, Yale University Greg Zacharias, Creighton University © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01143-4 — The Princess Casamassima Henry James , Edited by Adrian Poole Frontmatter More Information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES 1 Roderick Hudson 23 A Landscape Painter and Other Tales, 2 The American 1864–1869 3 Watch and Ward 24 A Passionate -

Habegger CV July 2014

Alfred Habegger CV July 2014 Vital facts Born February 6, 1941 Married to Nellie J. Weaver Contact Email: [email protected] Postal: 85400 Lost Prairie Road, Enterprise OR, 97828, USA Phone: 1-541-828-7768 Education Ph.D. in English, Stanford University, 1967 Dissertation: “Secrecy in the Fiction of Henry James” B.A., Bethel College (Kansas), 1962 Employment English Department, University of Kansas 1996 to date: Professor Emeritus and independent biographer 1982-96 Professor 1971-82 Associate Professor 1966-71 Assistant Professor 1972-73 Fulbright Lecturer in American Literature, University of Bucharest Fellowships 1997-98 and 1991-92 NEH Fellowships for University Teachers 1990 and 1988 Hall Center Research Fellowships 1986-87 and 1978-79 NEH Senior Independent Study Fellowships 1975 Huntington Library Fellowship 1962-66 Danforth Foundation Graduate Fellowship 1962-63 Woodrow Wilson Graduate Fellowship Books 2014 Masked: The Life of Anna Leonowens, Schoolmistress at the Court of Siam. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. 2001 My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson. Random House. In paperback with Modern Library from 2002 to present. Chapter 9 was reprinted in 2012 in Social Issues in Literature: Death and Dying in the Poetry of Emily Dickinson (Gale). A full Chinese translation was brought out in 2013 by Peking University Press. 1994 The Father: A Life of Henry James, Sr. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Paperback with U of Massachusetts Press 2002. 1989 Henry James and the “Woman Business”. Cambridge UP. Paperback 2004. 1982 Gender, Fantasy, and Realism in American Literature. Columbia UP. Paperback circa 1990. Prizes, Honors 2002 Oregon Book Award for My Wars Are Laid Away in Books 2001 Best-book honors for My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: One Hundred Best of 2001, Amazon.com Six Best Nonfiction Books of 2001, Maureen Corrigan, NPR’s Fresh Air 2 Book World Raves, Washington Post (Dec. -

Andover-1913.Pdf (7.550Mb)

TOWN OF ANDOVER ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Receipts and Expenditures ««II1IUUUI«SV FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING JANUARY 13, 1913 ANDOVER, MASS. THE ANDOVER PRESS *9 J 3 CONTENTS Almshouse Expenses, 7i Memorial Day, 58 Personal Property at, 7i Memorial Hall Trustees' Relief of, out 74 Report, 57, 121 Repairs on, 7i Miscellaneous, 66 Superintendent's Report, 75 Moth Suppression, 64 Animal Inspector, 86 Notes Given, Appropriations, 1912, 17 58 Art Gallery, 146 Notes Paid, 59 Assessors' Report 76 Overseers of Poor, 69 Assets, 93 Park Commissioner, 56 Auditor's Report, 105 Park Commissioners' Report 81 Board of Health, 65 Playstead, 55 Board of Public Works, Appen dix, Police, 53, 79 Sewer Maintenance, 63 Sewer Sinking Funds, 63 Printing and Stationery, 55 Water Maintenance, 62 Punchard Free School, Report Water Construction, 63 of Trustees, 101 Water Sinking Funds, 63 Repairs on old B. V. School, 68 Bonds, Redemption of, 62 Schedule of Town Property, 82 Collector's Account, 89 Schoolhouses, 29 Cornell Fund, 88 Schools, 23 County Tax, 56 School Books and Supplies, 3i Daughters of Revolution 68 Dog Tax 56 Selectmen's Report, 23 Dump, care of 58 Sidewalks, 42 Earnings Town Horses, 48 Soldiers' Relief, 74 Elm Square Improvements, 43 Snow, Removal of, 43 Fire Department, 51 77 Spring Grove Cemetery, 57, 87 Haggett's Pond Land, 68 State Aid, 74 Hay Scales, 58 State Tax, 55 Highways and Bridges, 33 Street Lighting, 50 Highway Surveyor, 46 Street List, 109 Horses and Drivers, 4i Town House, 54 Insurance, 63 Town Meeting, 7 Interest on Notes and Funds, 59 Town Officers, Liabilities, ior 4, 49 Town Warrant, 117 Librarian's Report, 125 Account, Macadam, 35 Treasurer's 93 Andover Street, 37 Tree Warden, 50 Salem Street, 39 Report, 85 TOWN OFFICERS, 1912 Selectmen, Assessors and Overseers of the Poor HARRY M. -

2395-1885 ISSN -2395-1877 Research Paper Impact Factor

IJMDRR Research Paper E- ISSN –2395-1885 Impact Factor - 2.262 Peer Reviewed Journal ISSN -2395-1877 THE UNCONVENTIONAL WOMEN IN THE PLAYS OF GEORGE BERNARD SHAW S.Jeyalakshmi Assistant Professor of English, PG Department of English (UA),Kongunadu Arts & Science College, Coimbatore . George Bernard Shaw was a committed socialist, a successful, controversial dramatist, an inspired theatre director of his own work and an influential commentator on contemporary music, drama and fine art. In all his endeavors he demonstrated an indefatigable zeal to reform existing social conditions, sterile theatrical conventions and outworn artistic orthodoxies. Shaw’s opinions on art and artists are scattered throughout his works, in his critical and journalistic writing, in letters and notebooks, as well as in his plays and the prefaces to them. He wrote essays of very high quality which are still read and praised. More than half a century after they were first printed. Shaw had moved to London because he felt that London was the literary centre of the English language. He occupied a central position from the opening of the modern period to his last play in 1950. Shaw dominates the theatre from 1890 right through to the Second World War. In play after play, in preface after preface, he has presented his analysis of the evils and errors of the time and has indicated his own solutions. He has constantly infused into his ideas. The stage-platform has given him the opportunity of shattering numerous false idols and also of awakening minds to thoughts beyond the superficial conventions. Feminist ideas spread among the educated female middle classes and the women's suffrage movements gained momentum of the Victorian Era.