The World Beautiful in Books TO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

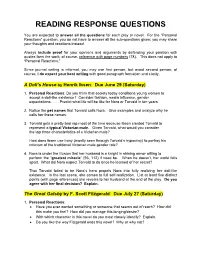

Reading Response Questions

READING RESPONSE QUESTIONS You are expected to answer all the questions for each play or novel. For the “Personal Reactions” question, you do not have to answer all the sub-questions given; you may share your thoughts and reactions instead. Always include proof for your opinions and arguments by defending your position with quotes form the work; of course, reference with page numbers (78). This does not apply to “Personal Reactions.” Since journal writing is informal, you may use first person, but avoid second person; of course, I do expect your best writing with good paragraph formation and clarity. A Doll’s House by Henrik IBsen: Due June 29 (Saturday) 1. Personal Reactions: Do you think that society today conditions young women to accept a doll-like existence? Consider fashion, media influence, gender expectations . Predict what life will be like for Nora or Torvald in ten years. 2. Notice the pet names that Torvald calls Nora. Give examples and analyze why he calls her these names. 3. Torvald gets a pretty bad rap most of the time because Ibsen created Torvald to represent a typical Victorian male. Given Torvald, what would you consider the top three characteristics of a Victorian male? How does Ibsen use irony (mostly seen through Torvald’s hypocrisy) to portray his criticism of the traditional Victorian male gender role? 4. Nora is under the illusion that her husband is a knight in shining armor willing to perform the “greatest miracle” (93, 112) if need be. When he doesn’t, her world falls apart. What did Nora expect Torvald to do once he learned of her secret? That Torvald failed to be Nora’s hero propels Nora into fully realizing her doll-like existence. -

Lilian Whiting?

lilian Whiting ? Watts Tun WO L B U IFUL First Sat in R D EA T . Tu n WO L B A IF L Secon dSeria l R D E UT U . ' Third Series Ta n WO RLD a rwux “ m m TH The St r of a Summer An n a DEA . o y Fn on D ML N S N an d Other Poems REA A D E T, A STUDY or ELI ! ABETH BARRETT Bn o wume Tun S r mrrmu . Sxe mn ca n cn KATE F xn w : A REC O RD RLD A WO B E UTIFUL. LILIAN WHITING “ ” AUTHOR or r un won w nu a 'rxm (n a s'r AND sworn) ’ ‘ ” su ms ), n on DRBAllu DlD Sn n r, u m ” ' m Dm r u. n rc. ‘ Tbe flower d nfe ls a glh wlthmt money andwlthout grlce. Dw r m B sup e e gm0! the gods can n either be discussednor deserved. Q lieve in ha i x e it ma k r In u 11 1 ' pp ness ; e p ct ; e room fo it yo }: 6. m ‘ And Ha ppin eas is of th e M& h gted mor al an dd ‘ ' ’ Im t s, escends on ly on the garlandedalta rso bet wczslJpw s. B O S T O N LITTLE MPA , O NY. est “5th BY Repai rs BROTHERS. Gnihmitg i3m n AND Sou C MB I G U. S. A. Joa n Ws o , A R D E, V . E. W N H TE . -

Contracting Female Marriage in Anthony Trollope's Can You Forgive Her? Review By: SHARON MARCUS Nineteenth-Century Literature, Vol

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Contracting Female Marriage in Anthony Trollope's Can You Forgive Her? Review by: SHARON MARCUS Nineteenth-Century Literature, Vol. 60, No. 3 (December 2005), pp. 291-325 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ncl.2005.60.3.291 . Accessed: 20/02/2013 16:42 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Nineteenth-Century Literature. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Wed, 20 Feb 2013 16:42:31 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Contracting Female Marriage in Anthony Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her? SHARON MARCUS ∞s one of literature’s most assiduous and complacent manufacturers of mar- riage plots, Anthony Trollope seems a perverse choice for inclu- sion in a discussion of lesbians and Victorian literary aesthetics, plausible only as a figure of that conjunction’s implausibility. We know the routine: marriage is the enemy of lesbian desire, and realist novels can represent passion between women only as a subversion of the natural, social, and aesthetic order upheld by marriage. -

Book Reviews and Notes

MISCELLANEOUS. i^Os " Thou hast unmasked a nation falsely clari In altruistic garb, revealed a land Blind to distinctions between good and bad. And smiting Liberty with ruthless hand." The accusation is neither fair nor just, and can only be uttered by one who has no idea of the difficulty of the situation. repeat that our government made mistakes in We the very beginning ; but there is no justification for going to the extreme of slandering President McKinley by saying : "Whether as tool or tyrant Histor\'s pen L'pon the nation's scroll of lasting shame Shall pillory in letters black thy name. Time can alone adjudge." It is the duty of our nation to establish order in the Philippines, and to give the Filipinos full liberty of home government, retaining for the United States gov- ernment nothing except perhaps the possession of Cavite together with other stra- tegic points of the harbor of Manila, and the recognition of a protectorate. Yet the latter should be drawn up in the form of an alliance, as an older brother would treat a younger brother, with rights similar to those the territories of the United States possessed, and nothing should be contained in the treaty which might savor of imperialism or indicate the conception that the Filipino republic is subject to the United States. The best plan may prove to be a division of the territory of the Philippines into various states with different constitutions according to local requirements, ethnological as well as religious. The Mussulmans, the various mountain tribes, the Filipinos, the European colonists of the city of Manila, the Chinese colonists, etc., are too disparate elements to enter as homogeneous ingredients into the plan of a comprehensive Philippine Republic. -

Andover-1913.Pdf (7.550Mb)

TOWN OF ANDOVER ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Receipts and Expenditures ««II1IUUUI«SV FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING JANUARY 13, 1913 ANDOVER, MASS. THE ANDOVER PRESS *9 J 3 CONTENTS Almshouse Expenses, 7i Memorial Day, 58 Personal Property at, 7i Memorial Hall Trustees' Relief of, out 74 Report, 57, 121 Repairs on, 7i Miscellaneous, 66 Superintendent's Report, 75 Moth Suppression, 64 Animal Inspector, 86 Notes Given, Appropriations, 1912, 17 58 Art Gallery, 146 Notes Paid, 59 Assessors' Report 76 Overseers of Poor, 69 Assets, 93 Park Commissioner, 56 Auditor's Report, 105 Park Commissioners' Report 81 Board of Health, 65 Playstead, 55 Board of Public Works, Appen dix, Police, 53, 79 Sewer Maintenance, 63 Sewer Sinking Funds, 63 Printing and Stationery, 55 Water Maintenance, 62 Punchard Free School, Report Water Construction, 63 of Trustees, 101 Water Sinking Funds, 63 Repairs on old B. V. School, 68 Bonds, Redemption of, 62 Schedule of Town Property, 82 Collector's Account, 89 Schoolhouses, 29 Cornell Fund, 88 Schools, 23 County Tax, 56 School Books and Supplies, 3i Daughters of Revolution 68 Dog Tax 56 Selectmen's Report, 23 Dump, care of 58 Sidewalks, 42 Earnings Town Horses, 48 Soldiers' Relief, 74 Elm Square Improvements, 43 Snow, Removal of, 43 Fire Department, 51 77 Spring Grove Cemetery, 57, 87 Haggett's Pond Land, 68 State Aid, 74 Hay Scales, 58 State Tax, 55 Highways and Bridges, 33 Street Lighting, 50 Highway Surveyor, 46 Street List, 109 Horses and Drivers, 4i Town House, 54 Insurance, 63 Town Meeting, 7 Interest on Notes and Funds, 59 Town Officers, Liabilities, ior 4, 49 Town Warrant, 117 Librarian's Report, 125 Account, Macadam, 35 Treasurer's 93 Andover Street, 37 Tree Warden, 50 Salem Street, 39 Report, 85 TOWN OFFICERS, 1912 Selectmen, Assessors and Overseers of the Poor HARRY M. -

Report of the Librarian

216 American Antiquarian Society [Oct., REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN "My library was dukedom large enough. " —Tempest, i:2 HEN Joseph's brethren came to his adopted W country during the seven lean years, they were made happy by discovering an abundance of food stored up for their need. And so it is with the historians and college professors from the far corners of the United States who flock to us all the year long, but especially during the summer vacation and the Christmas holidays, eager for our books and newspaper files, our manuscripts, maps and prints, for which they have hungered during the months when they had available only the less fortunately stored historical granaries of their various institutions. From Florida to Vancouver they have journeyed to Worcester in ever-increasing numbers to buy with their enthusiastic appreciation the rich grain of our histori- cal, biographical, and literary resources. As we watch them at their work, we cannot but share their enthu- siasm when they find here the varied materials they need for the scholarly work in which they are engaged. A Seventh Day Adventist historian from Washing- ton found our collections particularly rich in the rare periodicals, pamphlets, and broadsides relating to the Millerite delusion. A business historian was delighted with our wealth of editions of the early manuals of bookkeeping which he needed for his bibliography. A Yale graduate' student delved into our source material on the question of war guilt at the beginning of the Civil War. A Radcliffe graduate was made happy with an abundance of material on the practice of medicine in Colonial days. -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939 -

How to Read Literature Like a Professor Notes

How to Read Literature Like a Professor (Thomas C. Foster) Notes Introduction Archetypes: Faustian deal with the devil (i.e. trade soul for something he/she wants) Spring (i.e. youth, promise, rebirth, renewal, fertility) Comedic traits: tragic downfall is threatened but avoided hero wrestles with his/her own demons and comes out victorious What do I look for in literature? - A set of patterns - Interpretive options (readers draw their own conclusions but must be able to support it) - Details ALL feed the major theme - What causes specific events in the story? - Resemblance to earlier works - Characters’ resemblance to other works - Symbol - Pattern(s) Works: A Raisin in the Sun, Dr. Faustus, “The Devil and Daniel Webster”, Damn Yankees, Beowulf Chapter 1: The Quest The Quest: key details 1. a quester (i.e. the person on the quest) 2. a destination 3. a stated purpose 4. challenges that must be faced during on the path to the destination 5. a reason for the quester to go to the destination (cannot be wholly metaphorical) The motivation for the quest is implicit- the stated reason for going on the journey is never the real reason for going The real reason for ANY quest: self-knowledge Works: The Crying of Lot 49 Chapter 2: Acts of Communion Major rule: whenever characters eat or drink together, it’s communion! Pomerantz 1 Communion: key details 1. sharing and peace 2. not always holy 3. personal activity/shared experience 4. indicates how characters are getting along 5. communion enables characters to overcome some kind of internal obstacle Communion scenes often force/enable reader to empathize with character(s) Meal/communion= life, mortality Universal truth: We all eat to live, we all die. -

Henry James and Romantic Revisionism: the Quest for the Man of Imagination in the Late Work

HENRY JAMES AND ROMANTIC REVISIONISM: THE QUEST FOR THE MAN OF IMAGINATION IN THE LATE WORK A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (OF ENGLISH ) By Daniel Rosenberg Nutters May 2017 Examining Committee Members: Daniel T. O’Hara, Advisory Chair, English Alan Singer, English Steve Newman, English Robert L. Caserio, External Member, Pennsylvania State University Jonathan Arac, External Member, University of Pittsburgh © Copyright 2017 by Daniel Rosenberg Nutters All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This study situates the late work of Henry James in the tradition of Romantic revisionism. In addition, it surveys the history of James criticism alongside the academic critique of Romantic-aesthetic ideology. I read The American Scene, the New York Edition Prefaces, and other late writings as a single text in which we see James refashion an identity by transforming the divisions or splits in the modern subject into the enabling condition for renewed creativity. In contrast to the Modernist myth of Henry James the master reproached by recent scholarship, I offer a new critical fiction – what James calls the man of imagination – that models a form of selfhood which views our ironic and belated condition as a fecund limitation. The Jamesian man of imagination encourages the continual (but never resolvable) quest for a coherent creative identity by demonstrating how our need to sacrifice elements of life (e.g. desires and aspirations) when we confront tyrannical circumstances can become a prerequisite for pursuing an unreachable ideal. This study draws on the work of post-war Romantic revisionist scholarship (e.g. -

Katharine Susan Anthony and the Birth of Modern Feminist Biography, 1877-1929

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Féminisme Oblige: Katharine Susan Anthony and the Birth of Modern Feminist Biography, 1877-1929 Anna C. Simonson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1992 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Féminisme Oblige: Katharine Susan Anthony and the Birth of Modern Feminist Biography, 1877-1929 by Anna Simonson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 ANNA SIMONSON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Nasaw Date Chair of Examining Committee Helena Rosenblatt Date Executive Officer Kathleen D. McCarthy Blanche Wiesen Cook Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Féminisme Oblige: Katharine Susan Anthony and the Birth of Modern Feminist Biography, 1877-1929 By Anna Simonson Advisor: David Nasaw Féminisme Oblige examines the life and work of Katharine Susan Anthony (1877-1965), a feminist, socialist, and pacifist whose early publications on working mothers (Mothers Who Must Earn [1914]) and women’s movements in Europe (Feminism in Germany and Scandinavia [1915]) presaged her final chosen vocation as a feminist biographer. -

And Charlotte Smith (1840-1917)

Scribbling Women as Entrepreneurs: Kate Field (1838-96) and Charlotte Smith (1840-1917) Autumn Stanley Institutefor HistoricalStudy Berkeley,California Two women outwardlymore different than Mary Katherine Keemle Field andCharlotte Odlum Smith can hardly be imagined.Kate wasstrikingly attractive--oftencalled "bonny Kate Field." Charlotte, though not unattractive, wassimply never spoken of in suchterms. • Kate Field wasby somelights a childof privilege. Thoughher family wasnot wealthy,as the only childshe was much indulged, given the best St. Louis schooling.A wealthyaunt and unclegave her further schoolingin Bostonand took her to Europe for two years. The Odlums,by contrast,had sevenchildren, three of whom died in infancy[25, A]. Charlotte'sown poor health reportedlyinterrupted her schooling[15, p. 756]. WhateverCharlotte's father, Richard Odium, did for a living,it evidentlydid not suffice,for CatherineOdium was obliged to keep boarders[24a, b; 1; 2]. At Richard'sdeath, Charlotte became the "manof the family"at age 16. IKatewas petite, "very slender and graceful, with a wealth of chestnut hair falling in clustering curls,...faircomplexion and luminousblue eyes"[29, 37]. Many men, includingsome famous literarynames, fell in lovewith her or foundthemselves charmed. Biographical information on Field,where not specificallyreferenced, comes from References29, 8, and (variousissues of) 6. Charlottewas tall and, thoughattractive as a younggirl [25, Kirby and Lee depositions], became focused on her reforms to the exclusion of worries about attractiveness to men. As a PittsburghLeader reporter put it in 1893[12], Miss Smithis the pictureof earnestnessand strength. Her everythought and purpose has evidentlybeen given to her noble life work,...elevatingthe conditionof the wage-earnersof her sexand compelling from employers[equal pay for equalwork]. -

2010 Exam Day Lunch Schedule

Ontario H. S. 2016-17 English Department Reading Material Freshmen Books: Summer: Animal Farm School Year: To Kill a Mockingbird Romeo and Juliet The Odyssey Sophomore Books Summer: Of Mice and Men ...alternative The Pearl Honors: Summer: The Hunger Games by Collins Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card School Year: Dover Thrift edition of Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton Dover Thrift edition of Bullfinch's Mythology Julius Caesar by Shakespeare Lord of the Flies by William Golding Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes Twelve Angry Men by Reginald Rose A Long Way Gone by Ishmael Beah Junior Books: Summer: Celia Garth by Gwen Bristow Recommended- not required: Celebrate Liberty! Famous Patriotic Speeches and Sermons Complied by David Barton Thomas Paine’s Common Sense School Year: 1984 by Orwell The Scarlet Letter by Hawthorne The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Twain The Athena Project by Brad Thor Anthem by Ayn Rand Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand Salem’s Lot by Stephen King Advanced Placement: The Language of Composition: Reading. Writing. Rhetoric by Shea(2013) 5 Steps to a 5 AP English Language : McGraw Hill American Literature opposite College Credit +: Celia Garth by Gwen Bristow Senior Books: Summer: No Fear Shakespeare: Hamlet by Shakespeare School Year: Dover Thrift edition of Daisy Miller by James Dover Thrift Edition of A Doll’s House by Ibsen Dover Thrift Edition of Metamorphosis by Kafka Dover Thrift edition of The Importance of Being Ernest by Wilde Novel of Choice from the Multi-Genre book list (200+ books) Textbook: Literature