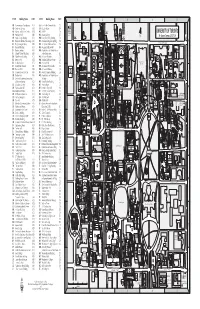

Helen Kemp's Map of the University of Toronto, 1932

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-21 STUDENT-ATHLETE HANDBOOK Your Mental Health Is Important!

VARSITY BLUES 2020-21 STUDENT-ATHLETE HANDBOOK Your mental health is important! In any given year, 1 in 5 Canadians experience a mental health illness* Mental Health Resources For YOU EMBEDDED COUNSELLOR U OF T MY SSP GOOD 2 TALK Book your confidential appointment Talk to Someone Right Now with 24/7 After hours? Always available 24 with Health & Wellness: Emergency Counseling Services: hours a day 416-978-8030 (Option 5) - Identify yourself My SSP: 1-844-451-9700 as a varsity athlete. Outside North America: 001-416-380- 6578 *According to CAMH Centre for Addiction and Mental Health ii | Student-Athlete Handbook 2020–21 Table of Contents Varsity Blues Student-Athlete Rights 4 Section 1 A Tradition of Excellence 5 Section 2 Intercollegiate and High Performance Sport Model 7 Section 3 Varsity Blues Expectations of Behaviour 9 Section 4 Eligibility 17 Section 5 Student-Athlete Services 19 Section 6 Athletic Scholarships and Financial Aid Awards 24 Section 7 Intercollegiate Program - Appeal Procedures 26 Section 8 Health Care 28 Section 9 Leadership and Governance 30 Section 10 Frequently Asked Questions 31 Safety Information for Students, Staff and Faculty 32 Helpful University Resources 33 Important Numbers Executive Director of Athletics Assistant Manager, Student-Athlete Services Mental Health Resources For YOU (Athletic Director) Steve Manchur Beth Ali 416-946-0807 416-978-7379 [email protected] [email protected] Manager, Marketing and Events Manager, Intercollegiate Sport Mary Beth Challoner Melissa Krist 416-946-5131 416-946-3712 [email protected] [email protected] Coordinator, Athletic Communications Assistant Manager, Intercollegiate Jill Clark Blue & White and Club Sports 416-978-4263 Kevin Sousa [email protected] 416-978-5431 [email protected] Student-Athlete Handbook 2020–21 | 1 About the University of Toronto The University of Toronto was founded as King’s College in 1827 and has evolved into a large and complex institution. -

3D Map1103.Pdf

CODE Building Name GRID CODE Building Name GRID 1 2 3 4 5 AB Astronomy and Astrophysics (E5) LM Lash Miller Chemical Labs (D2) AD WR AD Enrolment Services (A2) LW Faculty of Law (B4) Institute of AH Alumni Hall, Muzzo Family (D5) M2 MARS 2 (F4) Child Study JH ST. GEORGE OI SK UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO 45 Walmer ROAD BEDFORD AN Annesley Hall (B4) MA Massey College (C2) Road BAY SPADINA ST. GEORGE N St. George Campus 2017-18 AP Anthropology Building (E2) MB Lassonde Mining Building (F3) ROAD SPADINA Tartu A A BA Bahen Ctr. for Info. Technology (E2) MC Mechanical Engineering Bldg (E3) BLOOR STREET WEST BC Birge-Carnegie Library (B4) ME 39 Queen's Park Cres. East (D4) BLOOR STREET WEST FE WO BF Bancroft Building (D1) MG Margaret Addison Hall (A4) CO MK BI Banting Institute (F4) MK Munk School of Global Affairs - Royal BL Claude T. Bissell Building (B2) at the Observatory (A2) VA Conservatory LI BN Clara Benson Building (C1) ML McLuhan Program (D5) WA of Music CS GO MG BR Brennan Hall (C5) MM Macdonald-Mowat House (D2) SULTAN STREET IR Royal Ontario BS St. Basil’s Church (C5) MO Morrison Hall (C2) SA Museum BT Isabel Bader Theatre (B4 MP McLennan Physical Labs (E2) VA K AN STREET S BW Burwash Hall (B4) MR McMurrich Building (E3) PAR FA IA MA K WW HO WASHINGTON AVENUE GE CA Campus Co-op Day Care (B1) MS Medical Sciences Building (E3) L . T . A T S CB Best Institute (F4) MU Munk School of Global Affairs - W EEN'S EEN'S GC CE Centre of Engineering Innovation at Trinity (C3) CHARLES STREET WEST QU & Entrepreneurship (E2) NB North Borden Building (E1) MUSEUM VP BC BT BW CG Canadiana Gallery (E3) NC New College (D1) S HURON STREET IS ’ B R B CH Convocation Hall (E3) NF Northrop Frye Hall (B4) IN E FH RJ H EJ SU P UB CM Student Commons (F2) NL C. -

Toronto Academic Promotional CV Report

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Igor Jurisica Tier I Canada Research Chair in Integrative Cancer Informatics 2011-2018 Senior Scientist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Professor at University of Toronto A. Date Curriculum Vitae was Prepared: July 2015 B. Biographical Information Primary Office Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network Toronto Medical Discovery Tower, Room 11-314 IBM Life Sciences Discovery Centre 101 College Street Toronto, Ontario M5G 1L7 Telephone 416-581-7437 Email [email protected] URL http://www.cs.utoronto.ca/~juris 1. EDUCATION Degrees Jan 1993 – Jan 1998 Ph.D. University of Toronto, Department of Computer Science. Thesis title: TA3: Theory, implementation, and applications of similarity-based retrieval for case-based reasoning. Supervisor: Profs. J. Mylopoulos, Univ. of Toronto; J. Glasgow, Queen's Univ. Sep 1991 – Dec 1992 M.Sc. Univ. of Toronto, Dept. of Computer Science. Thesis title: Query optimization for knowledge base management systems; A machine learning approach. Supervisor: Prof. J. Mylopoulos, Univ. of Toronto; Dr. R. Greiner, Siemens Research. Sep 1986 – Jun 1991 Dipl. Ing, in Electrical Engineering (M.Sc. equivalent).Slovak Technical University in Bratislava, Slovakia. Thesis title: Machine learning in expert systems. Supervisor: Prof. L. Harach. 2. EMPLOYMENT Current Appointments Mar 2008 – present Senior Scientist, Ontario Cancer Institute/Princess Margaret Hospital, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Jul 2012 – present Professor at the Department of Computer Science -

Facts & Figures

1 FandF_2011.pdf 1 2/2/2012 3:20:47 PM C Facts & M Y CM Figures MY CY CMY K 2017 Facts and Figures is prepared annually by the Office of Planning & Budget. Facts and Figures provides answers to some of the most frequently asked questions about the University. It is designed and organized to serve as a useful and reliable source of reference information from year to year. The reader of Facts and Figures should take care when attempting to use the enclosed information comparatively. While some definitions are common to other universities, many others are not. Our office maintains some comparative databases and has access to others. Please contact us for assistance when using Facts and Figures comparatively. Each year we try to improve Facts and Figures to make it as useful as possible. We are always grateful for suggestions for improvement. Facts and Figures, and other official publications of the University can also be accessed on the internet at https://www.utoronto.ca/about-u-of-t/reports-and-accountability . Facts & Figures 2017 Project Manager: Xuelun Liang Xuelun can be reached via e-mail at: [email protected] Contributors include: Brian Armstrong, Lucas Barber, Michelle Broderick, Douglas Carson, Helen Chang, Helen Choy, Maya Collum, Jeniffer Francisco, Phil Harper, Mark Leighton, Shuping Liu, Derek Lund, Klara Maidenberg, Len McKee, Zoran Piljevic, Jennifer Radley, José Sigouin, Russell Smith, Skandha Sunderasen, and Donna Wall. Office of Planning and Budget Room 240, Simcoe Hall 27 King's College Circle Toronto, Ontario M5S 1A1 CONTENTS Part A General 3 1. -

Book Template

CATALOG 2009/2010 A Coeducational Independent University Offering Bachelor’s and Master’s Degrees 1525 Greenspring Valley Road • Stevenson, Maryland 21153-0641 100 Campus Circle • Owings Mills, Maryland 21117-7803 For inquiries on: Contact: Undergraduate Programs and Policies Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean Accelerated Undergraduate, Graduate Dean, School of Graduate and Professional Studies Admissions and Financial Aid Vice President, Enrollment Management Payment of University Charges Student Solution Center Transcripts, Registration, Academic Records, Graduation Registrar Student Services Vice President for Student Affairs Public Information Vice President for Marketing and Public Relations Athletics Athletic Director Career Services Executive Director, Career Services For further information, write: STEVENSON UNIVERSITY 1525 Greenspring Valley Road Stevenson, MD 21153-0641 Phone (410) 486-7000 Toll free (877) 468-6852 Fax (443) 352-4440 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.stevenson.edu Visitors to the University are always welcome. On weekdays, student guides are available through the Admissions Office. Information sessions and campus tours are available during the week and on select weekends. Please make arrangements in advance by email or telephone. The Stevenson University catalog is published on an annual basis. Information in this catalog is current as o f June 2009. To obtain the most updated information on programs, policies, and courses, consult the University web site at <www.stevenson.edu>. Stevenson University admits students of any race, color, sex, religion, national or ethnic origin to all of the rights, privileges, programs, benefits, and activities generally accorded or made available to students at the University. It does not discrimina te on the basis of race, color, sex, religion, disability, and national or ethnic origin in the administration of its education policies, admission policies, scholarship and loan programs, and other university-administered programs. -

Report of the Task Force on University of Toronto Radio

University of Toronto Report of the Task Force on University of Toronto Radio Final Report – April 19, 1999 RTF Report Final.doc / JD Task Force on University of Toronto Radio Final Report – April 19, 1999 Task Force on University of Toronto Radio Final Report – April 19, 1999 © Copyright 1999, University of Toronto No part of this report may be reproduced in any form without the express written consent of the University of Toronto. Office of Student Affairs 214 College Street, Room 307 Toronto, ON M5T 2Z9 Phone: (416) 978-5536 Fax: (416) 971-2037 Email: <[email protected]> Web: <http://www.campuslife.utoronto.ca> ii Contents Final Report – April 19, 1999 Task Force on University of Toronto Radio CCoonntteennttss SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS V E. A PLAN FOR THE FU TURE 28 1. Preface.............................................................................28 2. Vision...............................................................................30 DEFINITIONS AND ABBREVIATIONS XV 3. Partnerships.....................................................................31 (a) CIUT as an Extra-Curricular Activity..........................31 (b) CIUT as a Co-Curricular Activity................................32 A. INTRODUCTION 1 (c) CIUT as an Outreach and Promotional Resource for 1. Establishment of the Task Force........................................1 the University and a Community Service .................33 2. Membership ......................................................................1 4. Finances...........................................................................33 -

Report of the Project Planning Committee for Trinity College in The

FOR ENDORSEMENT AND PUBLIC CLOSED SESSION FORWARDING TO: Executive Committee SPONSOR: Scott Mabury, Vice President, Operations and Real Estate Partnerships PRESENTER: As above CONTACT INFO: [email protected] DATE: June 9, 2020 for June 16, 2020 AGENDA ITEM: 3(e.) ITEM IDENTIFICATION: Capital Project: Report of the Project Planning Committee for Trinity College in the University of Toronto New Student Residence & Academic Building - The Lawson Centre for Sustainability JURISDICTIONAL INFORMATION: Pursuant to section 4.2.3. of the Committee’s terms of Reference, “…the Committee considers reports of project planning committees and recommends to the Academic Board approval in principle of projects (i.e. space plan, site, overall cost and sources of funds).” Under the Policy on Capital Planning and Capital Projects, “…proposals for capital projects exceeding $20 million must be considered by the appropriate Boards and Committees of Governing Council on the joint recommendation of the Vice-President and Provost and the Vice-President, University Operations. Normally, they will require approval of the Governing Council. Execution of such projects is approved by the Business Board. If the project will require financing as part of the funding, the project proposal must be considered by the Business Board.” Trinity College is governed separately from the University of Toronto and subject to its own approvals processes. As per Trinity College Statutes, there is a tricameral governance model in place: Senate (academic and policy matters), Board of Trustees (“Board” - business and financial matters) and Corporation (broad oversight). Major decisions (e.g., hiring architects, hiring construction management, final design approval, approval of funding and expenditures, business model and financing plan, etc.) are subject to oversight by these bodies and their committees, under the guidance of the above-named senior staff and governance leaders. -

UTSC from St

THE VARSITY STUDENT HANDBOOK VOL. XXXV LETTER FROM 21 Sussex Avenue, Suite 306 Toronto, ON, M5S 1J6 THE EDITOR Phone: 416-946-7600 thevarsity.ca YOU’VE ARRIVED. are part of the journey; take advantage of the resources to help you along the way, Editorial Board Your first steps on campus are the beginning from your college registrar to the many Editor-in-Chief of a journey. As in any adventure, there will available accessibility services (p. 21). Put [email protected] Danielle Klein be frustrations, excitement, and — whether yourself out there; join a club; make a few Handbook Editor they be the product of an amazing night mistakes. Soon enough, the confusion and Samantha Relich [email protected] out or a procrastinated term paper — some uncertainty of the first few months will Production Manager sleepless nights. fade into memory, and you will discover [email protected] Catherine Virelli Perhaps the most remarkable things that you really can do this. Managing Online Editor about starting university are the opportu- This guide is the product of our discoveries Shaquilla Singh [email protected] nities available to you and the chances you and journeys, and we hope it helps you find Design Editors have to push your boundaries and shape your own niche. It’s far from comprehensive, Kawmadie Karunanayake your experiences. You may be an aspiring but, hopefully, it will serve as a launch pad for Mari Zhou [email protected] scientist (p. 16), or maybe your dream is your own investigation — compiled by stu- Photo Editor to finally take centre stage (p. -

Residences on the St. George Campus

Residences on the St. George Campus The St. George campus offers residence at each of the seven colleges, Chestnut Residence, Graduate House or Student Family Housing. The more contemporary colleges feature updated residences, while the oldest colleges have more history. Each residence has its own intramural teams, events, governance, clubs and dining options. Each residence also has its own eligibility rules – some are open to all students, and others are open only to those studying in a certain academic program. There is a residence option to suit any need, including accessibility. Chestnut Residence Eligibility Chestnut Residence is open to the following students: - Arts & Science - Architecture - Engineering - Kinesiology & Physical Education - Music Cost range Cost range (2019-20): $16,699.62 – $19,877.62 Fees include a mandatory meal plan: If you have dietary concerns or questions you are welcome to contact the Residence Life Office Location/contact 89 Chestnut St. 416-585-3160 [email protected] www.chestnut.utoronto.ca Move-in dates Fall 2019: September 2 Winter 2020: January 6 Summer stays Yes – see summer housing for details. Accessibility • Low to medium lighting in carpeted corridors and stairwells • Natural lighting in residence rooms, supplemented by artificial • Adjustable air conditioning and heat in each room • Main entrance provides wheelchair access • Elevator access to all resident floors • 4 rooms designated as providing wheelchair access • Dining hall provides wheelchair access Features • 15-minute walk -

Student Awards and Benefactors

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 3 ADMISSION SCHOLARSHIPS 4 For newly-admitted students who register at Victoria College without transfer 4 credit, usually right after completing their secondary school studies. IN-COURSE SCHOLARSHIPS AND PRIZES 14 For students who have completed the First, Second, or Third Years of study toward 14 a Bachelor's degree. For award purposes, a year of study is defined as completion of 5.0 credits. PARTICIPATION AWARDS 78 Awarded in recognition of significant participation in extracurricular university life, 78 as well as excellent academic performance. SPECIAL AWARDS 82 Have special terms or require a special application procedure. 82 AWARDS FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDY ABROAD 86 Awarded for approved study abroad. 86 BURSARIES 89 Grants given for financial need. 89 GRADUATING AWARDS 100 Awarded at the time of graduation. They include medals awarded for outstanding 100 achievement over the entire period of work toward the degree. Most of the Victoria College medals are struck by the Royal Canadian Mint to designs created in 1993 by Professor David Blostein. POSTGRADUATE AWARDS 106 For graduates of Victoria College (i.e., students registered at Victoria College at the 106 time of their graduation from the University of Toronto) to enable them to begin or continue postgraduate studies. INDEX OF AWARDS 109 INTRODUCTION The many awards listed in this brochure have been established largely through gifts from individuals who, with only a few exceptions, were alumni or alumnae of Victoria College. Some gifts go back to Victoria's Cobourg period, 1836-1890; many are very recent donations. A significant number of awards have been funded through bequests, as graduates and friends have included Victoria University in their wills. -

Facts & Figures 2016

1 FandF_2011.pdf 1 2/2/2012 3:20:47 PM C Facts & M Y CM Figures MY CY CMY K 2016 Facts and Figures is prepared annually by the Office of Government, Institutional and Community Relations. Facts and Figures provides answers to some of the most frequently asked questions about the University. It is designed and organized to serve as a useful and reliable source of reference information from year to year. The reader of Facts and Figures should take care when attempting to use the enclosed information comparatively. While some definitions are common to other universities, many others are not. Our office maintains some comparative databases and has access to others. Please contact us for assistance when using Facts and Figures comparatively. Each year we try to improve Facts and Figures to make it as useful as possible. We are always grateful for suggestions for improvement. Facts and Figures, and other official publications of the University can also be accessed on the internet at https://www.utoronto.ca/about-u-of-t/reports-and-accountability Other official publications of the University can be found on the About U of T website: https://www.utoronto.ca/about-u-of-t/reports-and-accountability Facts & Figures 2016 Project Manager: Xuelun Liang Xuelun can be reached via e-mail at: [email protected] Contributors include: Brian Armstrong, Michelle Broderick, Douglas Carson, Helen Choy, Maya Collum, Jeniffer Francisco, Phil Harper, Richard Kellar, Mark Leighton, Shuping Liu, Derek Lund, Maureen Lynham, Klara Maidenberg, Len McKee, Nitish Mehta, Zoran Piljevi, Jennifer Radley, José Sigouin, Susan Senese, Russell Smith, Cindy Tse, Jeffrey Waldman, and Donna Wall. -

Assistantships and Fellowships in the Mathematical Sciences in 1982-1983 Supplementary List

il16 and 17)-Page 257 ta~Aellnformation- Page 27 5 ematical Society < 2. c 3 II> J~ cz 3 i"... w Calendar of AMS Meetings THIS CALENDAR lists all meetings which have been approved by the Council prior to the date this issue of the Notices was sent to press. The summer and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Association of America and the Ameri· can Mathematical Society. The meeting dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have yet been assigned. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated below. First and second announcements of the meetings will have appeared in earlier issues. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS presented at a meeting of the Society are published in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices which contains the program of the meet ing. Abstracts should be submitted on special forms which are available in many departments of mathematics and from the office of the Society in Providence. Abstracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the deadline for ab· stracts submitted for consideration for presentation at special sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For additional information consult the meeting announcement and the list of organizers of special sessions.