The Effects of CSR Initiatives and CSR Communication on Customers’ Responses and Satisfaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love Ain't Got No Color?

Sayaka Osanami Törngren LOVE AIN'T GOT NO COLOR? – Attitude toward interracial marriage in Sweden Föreliggande doktorsavhandling har producerats inom ramen för forskning och forskarutbildning vid REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköpings universitet. Samtidigt är den en produkt av forskningen vid IMER/MIM, Malmö högskola och det nära samarbetet mellan REMESO och IMER/MIM. Den publiceras i Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. Vid filosofiska fakulteten vid Linköpings universitet bedrivs forskning och ges forskarutbildning med utgångspunkt från breda problemområden. Forskningen är organiserad i mångvetenskapliga forskningsmiljöer och forskarutbildningen huvudsakligen i forskarskolor. Denna doktorsavhand- ling kommer från REMESO vid Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 533, 2011. Vid IMER, Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, vid Malmö högskola bedrivs flervetenskaplig forskning utifrån ett antal breda huvudtema inom äm- nesområdet. IMER ger tillsammans med MIM, Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, ut avhandlingsserien Malmö Studies in International Migration and Ethnic Relations. Denna avhandling är No 10 i avhandlingsserien. Distribueras av: REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärsstudier, ISV Linköpings universitet, Norrköping SE-60174 Norrköping Sweden Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, IMER och Malmö Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, MIM Malmö Högskola SE-205 06 Malmö, Sweden ISSN -

Artist Title Count PURPLE DISCO MACHINE FEAT. MOSS KENA & THEFIREWORKS KNOCKS 92 LEONY FADED LOVE 83 ONEREPUBLIC RUN 82 ATB FT

Artist Title Count PURPLE DISCO MACHINE FEAT. MOSS KENA & THEFIREWORKS KNOCKS 92 LEONY FADED LOVE 83 ONEREPUBLIC RUN 82 ATB FT. TOPIC & A7S YOUR LOVE 81 JUSTIN BIEBER FT. DANIEL CAESAR PEACHES 81 COLDPLAY HIGHER POWER 80 IMAGINE DRAGONS FOLLOW YOU 80 OLIVIA RODRIGO GOOD 4 YOU 80 REGARD X TROYE SIVAN X TATE MCRAE YOU 79 ALVARO SOLER MAGIA 74 RITON X NIGHTCRAWLERS FRIDAY 74 LOST FREQUENCES RISE 70 JONAS BLUE FT. AVA SOMETHING STUPID 69 THE WEEKND SAVE YOUR TEARS 69 KUNGS NEVER GOING HOME 68 ED SHEERAN BAD HABITS 68 JUSTIN WELLINGTON FEAT. SMALL JAM IKO IKO 67 MAJESTIC X BONEY M. RASPUTIN 67 ROBIN SCHULZ FT. FELIX JAEHN & ALIDA ONE MORE TIME 66 RAG'N'BONE MAN ALL YOU EVER WANTED 64 DUA LIPA LOVE AGAIN 63 JOEL CORRY FT. RAYE & DAVID GUETTA BED 63 JASON DERULO & NUKA LOVE NOT WAR 62 MEDUZA FT. DERMOT KENNEDY PARADISE 59 AVA MAX MY HEAD & MY HEART 58 DUA LIPA WE'RE GOOD 57 MARTIN GARRIX FEAT. BONO & THE EDGE WE ARE THE PEOPLE 57 JOEL CORRY HEAD AND HEART 56 CALVIN HARRIS FT. TOM GRENNAN BY YOUR SIDE 56 DOJA CAT FEAT. SZA KISS ME MORE 56 PINK ALL I KNOW SO FAR 54 OFENBACH FT. LAGIQUE WASTED LOVE 53 PINK + WILLOW SAGE HART COVER ME IN SUNSHINE 53 MALARKEY SHACKLES (PRAISE YOU) 50 MASTER KG FT. NOMCEBO JERUSALEMA 49 SIA & DAVID GUETTA FLOATING THROUGH SPACE 48 SUPER-HI & NEEKA FOLLOWING THE SUN 48 ALVARO SOLER FT. CALI Y EL DANDEE MANANA 44 MARCO MENGONI MA STASERA 42 AVA MAX EVERYTIME I CRY 41 TATE MCRAE YOU BROKE ME FIRST [LUCA SCHREINER41 REMIX] MAROON 5 LOST 40 OFENBACH & QUARTERHEAD HEAD SHOULDERS KNEES & TOES 38 PS1 FT. -

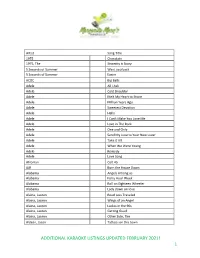

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Sorted by ARTIST * * * * Please Note That The

* * * * Sorted by ARTIST * * * * Please note that the artist could be listed by FIRST NAME, or preceded by 'THE' or 'A' Title Artist YEAR ----------------------------------------- ------------------------ ----- 7764 BURN BREAK CRASH 'ANYSA X SNAKEHIPS 2017 2410 VOICES CARRY 'TIL TUESDAY 1985 2802 GET READY 4 THIS 2 UNLIMITED 1995 9144 MOOD 24KGOLDN 2021 8180 WORRY ABOUT YOU 2AM CLUB 2010 2219 BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN 2001 6620 HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 DOORS DOWN 2003 1517 KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN 2000 5216 LET ME GO 3 DOORS DOWN 2005 0914 HOLD ON LOOSELY 38 SPECIAL 1981 8115 DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 2009 8214 MY FIRST KISS 3OH!3/ KE$HA 2010 7336 AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2014 8710 EASIER 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2019 7312 SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2014 8581 WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2018 8611 YOUNGBLOOD 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2018 7413 IN DA CLUB 50 CENT 2004 8758 ALL MY FRIENDS ARE FAKE 58TE McRAE 2020 2805 TOOTSIE ROLL 69 BOYZ 1995 8776 SAY SO 71JA CAT 2020 7318 ALREADY HOME A GREAT BIG WORLD 2014 7117 THIS IS THE NEW YEAR A GREAT BIG WORLD 2013 3109 BACK AND FORTH AALIYAH 1994 4809 MORE THAN A WOMAN AALIYAH 2002 1410 TRY AGAIN AALIYAH 2000 7744 FOOL'S GOLD AARON CARTER 2016 2112 I MISS YOU AARON HALL 1994 2903 DANCING QUEEN ABBA 1977 6157 THE LOOK OF LOVE (PART ONE) ABC 1982 8542 ODYSSEY ACCIDENTALS 2017 8154 WHATAYA WANT FROM ME ADAM LAMBERT 2010 8274 ROLLING IN THE DEEP ADELE 2011 8369 SOMEONE LIKE YOU ADELE 2012 5964 BACK IN THE SADDLE AEROSMITH 1977 5961 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 1973 5417 JADED AEROSMITH 2001 5962 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 1975 5963 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 1976 8162 RELEASE ME AGNES 2010 9132 BANG! AJR 2020 6906 I WANNA LOVE YOU AKON FEAT SNOOP DOGG 2007 7810 LOCKED UP AKON feat STYLES P. -

SONG ARTIST 375 Roar

# SONG ARTIST 400 We're All In This Together Ben Lee 399 Be The One Dua Lipa 398 Take My Breath Away Berlin 397 Treat You Better Shawn Mendes 396 The Fighter Keith Urban Feat Carrie Underwood 395 I'm Still On You're Side Jimmy Barnes 394 Dance Monkey Tones & I 393 Just Like Fire Pink 392 One Dance Drake Feat Wizkid & Kyla 391 Fire & The Flood Vance Joy 390 Hide Away Daya 389 Don't Wanna Know Maroon 5 Feat Kendrick Lamar 388 Stonger Kanye 387 Dancin with myself Billy Idol 386 London Calling Clash 385 Ain't Nobody (Loves Me Better) Felix Jaehn Feat Jasmine Thompson 384 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay & Justin Bieber 383 You Don’t Know Me Jax Jones Feat RAYE 382 You Need To Calm Down Taylor Swift 381 American Woman Lenny Kravitz 380 You Keep Me Hangin On Kim Wilde 379 Senorita Shawn Mendes & Camila Cabello 378 Whenever, Wherever Shakira 377 The Middle Zedd Feat Maren Morris & Grey 376 Get Lucky Daft Punk Feat Pharrell Williams 375 Roar Katy Perry 374 Heroes David Bowie 373 Hey Ya! Outkast 372 Left Outside Alone Anastasia 371 24K Magic Bruno Mars 370 In My Blood The Veronicas 369 Addicted To You Avicii 368 Welcome to the Jungle Guns N Roses 367 Scars To Your Beautiful Alessia Cara 366 Que Sera Justice Crew 365 I Love You Always Forever Betty Who 364 Strip That Down Liam Payne Feat Quavo 363 Starboy The Weeknd Feat Daft Punk 362 Issues Julia Michaels 361 Rather Be Clean Bandit Feat Jess Glynne 360 Your The Voice John Farnham 359 Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Feat Christina Aguilera 358 Am I Wrong Nico & Vinz 357 Take Me To Church Hozier 356 Mr Brightside -

Barents #Beingyounghere

#Barents #BeingYoungHere A journalistic expedition across the Barents region Organised by Barents Press Sweden and Nordic Journalist Centre 1 #Barents #BeingYoungHere A journalistic expedition across the Barents region ISBN 978-91-985034-1-8 © Författarna och Barents Press Sverige 2019 Printed in Russia Utgivare Journalistföreningen Barents Press Sverige, Box 356, 3124 Skellefteå, Apartment building in Apatity Sverige / Photo Mari Molkoselkä 2 3 Deltagere och bidragsgivare #Barents #BeingYoungHere till den här boken Tim Andersson, Barents Press Sverige A journalistic expedition across the Barents region (organizer, editor) Ole Rode Jensen, Nordiskt Journalistcenter (organizer, editor; graphics and layout) VID EN FÖRSTA ANBLICK handlar denna reportagebok Om man skulle våga sig på att på dessa första sidor om unga i Barentsregionen. Men, den handlar om sammanfatta vårt gemensamma projekt kan man SVERIGE så mycket mer. Genom de reportage som projektets nog konstatera att de unga som vi möter i boken Vendela Wikström internationella deltagare tillsammans har skapat får samtliga brinner för sin region, att skapa något Max Lewander vi som läsare även ta del av regionens utveckling. En bättre, att få möjligheten att stanna kvar och gemen- Karl Sundström region som är okänd för många av invånarna söder samt ta ansvar för klimatet. Skämtsamt brukar man Hiram Li Sergei Abrosimov in the driver’s seat om Tromsö, Luleå, Uleåborg och Apatity. En region säga att de i norr tar hand om varandra på grund av / Photo Vendela Wikström där ord som samarbete och fredlig samexistens klimatet, jag tror snarare att det handlar om en kärlek FINLAND präglar samtalen. och välvilja till sin ort. Mari Molkoselkä Jenna Louhela 4361 km på vägmätaren Barents Press har existerat i 25 år, dessa 25 år har Jag önskar dig trevlig läsning, och hoppas att ditt Sampo Nevalainen lagt grunden för ett stabilt nätverk av journalister intresse för denna spännande region växer. -

By Margaret Feinberg Awaken to the Nearness Of

CHAPTER EXTRACTS WONDER STRUCK BY MARGARET FEINBERG AWAKEN TO THE NEARNESS OF GOD In Wonderstruck, Margaret invites you to unearth the extraordinary moments in every day life, recognize the presence of God in the midst of your routine, and discover peace in knowing you’re wildly loved. Winsome yet compelling, whimsical yet profound, the stories from Wonderstruck will inspire you to fall in love anew with God. Wonderstruck consists of eleven chapters full of practical steps, challenging questions, intimate stories, and Biblical insights culminating in a 30 Days of Wonder Challenge. This book and Bible study are for anyone who wants to live astounded by God and walk in the fullness of all He offers. 1 TRANSFORMATIONAL COMMUNITY COMMUNITY TRANSFORMATIONAL “[Feinberg] succeeds in keeping the reader engaged, entertained, and edified . [She] raises questions that linger in the mind after the book is closed.” PUBLISHERS WEEKLY Margaret Feinberg is a modern-day David. With eyes on the heavens, His Word in hand, and all her heart turned towards His, she tells the wonders of His love in ways you’ve never known. Who in the world doesn’t need joy like this? ANN VOSKAMP Author of One Thousand Gifts “Feinberg turns exegesis into an art, delivering findings that invite the audience to touch, taste, smell, and see God’s handiwork throughout the Scriptures and in their own lives.” ED STETZER President, LifeWay Research We dangerously underestimate the power of wonder . Margaret recenters wonder at the heart of our relationship with God, with seismic results. This book shook my soul awake and made it impossible for me to continue following a God of my own design. -

Kygo X Donna Summer “Hot Stuff” Out

KYGO X DONNA SUMMER “HOT STUFF” OUT NOW Global superstar, producer and DJ, Kyrre Gørvell-Dahll – a.k.a Kygo releases a brand new remix of Donna Summer’s Grammy Award winning, platinum, #1 song “Hot Stuff” today via Sony Music International/Ultra Records/RCA Records. The original track was produced by Pete Bellotte and Giorgio Moroder and was ranked as one of Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time and was the lead single from Donna Summer’s album ‘Bad Girls’. Summer won the Grammy Award for Best Female Rock Vocal Performance in the inaugural year the award was given out for “Hot Stuff”. “Hot Stuff” comes alongside a brand new video produced by Lighthouse Films, directed by Bo Webb and shot by Brad Walker, starring Chase Stokes and Madelyn Cline who are best known as John B and Sarah Cameron from Netflix’s Outer Banks. Listen / Watch HERE – out now via Sony Music International/Ultra Records/RCA Records. Says Kygo, “Donna Summer is one of my favorite artists of all time. Her catalogue of music is brilliant and her vocals are unmatched. I am honored and humbled to get to work on an iconic track like “Hot Stuff”. This has always been one of those songs that instantly puts me in a good mood and I hope that this version can continue to bring joy and happiness to people who want to celebrate the legendary Donna Summer.” It’s been a big summer for Kygo who recently released his remix of Tina Turner’s “What’s Love Got To Do With It” to rave reviews as well as his critically acclaimed third full-length album Golden Hour which features his hit single “Lose Somebody” with OneRepublic as well as “Higher Love” with Whitney Houston, the latter of which has more than 651 million audio and video streams combined and charted at Top 40 radio. -

Shock and Awe, Sectarianism, and Violence in Iraq Post-2003

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Shock and Awe, Sectarianism, and Violence in Iraq Post-2003 Sarim Al-Rawi The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3869 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SHOCK AND AWE, SECTARIANISM, AND VIOLENCE IN IRAQ POST-2003 by SARIM AL-RAWI A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2020 [Ty pe text] [Type text] © 2020 SARIM AL-RAWI All Rights Reserved !ii Shock and Awe, Sectarianism, and Violence in Iraq Post-2003: A Case Study by Sarim Al-Rawi This manuscript has been read and approved for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Arts/International Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________ ____________________________ Date Samira Haj Thesis Advisor ___________________ ____________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK !iii ABSTRACT Shock and Awe, Sectarianism, and Violence in Iraq Post-2003: A Case Study by Sarim Al-Rawi Advisor: Dr. Samira Haj The violence systematically deployed upon the prosperous nation of Iraq in 2003 was directly influenced by the Shock and Awe doctrine set forth by Harlan K. -

Samsung Galaxy S21 5G

User manual Contents Features S Pen | Mobile continuity | Bixby | Biometric security | Dark mode Getting started Device layout: Galaxy S21 5G | Galaxy S21+ 5G | Galaxy S21 Ultra 5G Set up your device: Charge the battery | Wireless power sharing Start using your device: Turn on your device | Use the Setup Wizard | Transfer data from an old device | Lock or unlock your device | Side key settings | Accounts | Set up voicemail | Navigation | Navigation bar | Customize your home screen | S Pen | Bixby | Digital wellbeing and parental controls | Always On Display | Biometric security | Mobile continuity | Multi window | Edge panels | Enter text | Emergency mode Customize your home screen: App icons | Wallpaper | Themes | Icons | Widgets | Home screen settings | Easy mode | Status bar | Notification panel Camera and Gallery Camera: Navigate the camera screen | Configure shooting mode | AR Zone | Scene optimizer | Single take | Space Zoom | Record videos | Director’s view | Zoom-in mic | Camera settings Gallery: View pictures | Edit pictures | Play video | Video enhancer | Edit video | Share pictures and videos | Delete pictures and videos | Group similar images | Take a screenshot | Screen recorder Mobile continuity Link to Windows | Samsung DeX | Continue apps on other devices 2 SAM_G991U_G996U_G998U_EN_UM_TN_TLF_011421_FINAL Contents Samsung apps Galaxy Essentials | AR Zone | Bixby | Galaxy Shop | Galaxy Store | Galaxy Wearable | Game Launcher | PENUP | Samsung Free | Samsung Global Goals | Samsung Members | Samsung TV Plus | SmartThings | -

GLOBAL SUPERSTAR KYGO UNVEILS MUSIC VIDEO for NEW SINGLE “Remind Me to Forget” FEATURING MIGUEL WATCH HERE

GLOBAL SUPERSTAR KYGO UNVEILS MUSIC VIDEO FOR NEW SINGLE “Remind Me To Forget” FEATURING MIGUEL WATCH HERE DUO SET TO PERFORM ON The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon MAY 14TH! KIDS IN LOVE TOUR MAKES FINAL STOPS IN WASHINGTON D.C, BROOKLYN, NY, AND BOSTON, MA PURCHASE YOUR TICKETS HERE May 7th, 2018 - New York, NY- Today, global superstar/producer/DJ, Kyrre Gørvell-Dahll - a.k.a. Kygo, releases the music video for his explosive new single “Remind Me To Forget” with GRAMMY® Winner, Miguel. The visual showcases a ballerina performing a gritty emotional dance around a darkened, self- destructive home “leaving her mark” in the middle of the chaos. You can watch “Remind Me To Forget” here : http://smarturl.it/xRMTF Kygo performs his final four shows of his Phase 2 Kids In Love Tour- with back to back stops in Washington D.C at The Anthem, a performance in NY at the Barclays Center, wrapping up in Boston, MA at TD Garden. You can purchase tickets here. KIDS IN LOVE TOUR Monday, May 07, 2018- Washington, DC @ The Anthem Tuesday, May 8, 2018- Washington DC @ The Anthem Friday, May 11, 2018- Brooklyn, NY @ Barclays Center Saturday, May 12, 2018- Boston, MA @ TD Garden ABOUT KYGO Kygo is a Norwegian-born, world-renowned producer, songwriter, DJ and music marvel who has turned himself into an international sensation in unprecedented time. He was crowned Spotify’s Breakout Artist of 2015, as songs including “Firestone (feat. Conrad Sewell)” and “Stole The Show (feat. Parson James)”, which was certified gold or platinum in sixteen countries, helped him become the fastest artist to reach 1 billion streams on Spotify. -

'Remind Me to Forget' Feat. Miguel

KYGO Releases New Song Featuring MIGUEL “Remind Me To Forget” Set To Headline At Coachella Festival April 13th & April 20th Listen To “Remind Me To Forget” Here New York, NY - March 16th, 2018- Today, global superstar/producer/DJ, Kyrre Gørvell-Dahll, a.k.a Kygo, teams up with Grammy-Award Winner Miguel to release a brand new single titled “Remind Me To Forget” via Sony Music Sweden/Ultra Records/RCA Records. The new Kygo produced track infuses his upbeat tropical house sound mixed with Miguel’s seductive and sultry vocals to create an endlessly- playable melody. You can listen to the catchy single here: LINK? Praise For Kids In Love Album Kygo Displays Artistic Maturity on Sophomore Album 'Kids In Love'- Billboard We can't really expect anything less from the young, iconic tropical house prodigy. - EDM.COM Kygo steals the show, yet again, but this time, his sophomore studio album, Kids In Love, is the topic of 52000 conversation. - The Nocturnal Times Currently, Kygo is set for a double headline at Coachella Festival onApril 13th and April 20th while actively on the road for his rapidly selling Kids In Love Tour. Phase 2 dates have been added and include stops in Seattle, WA, Berkeley, CA, Red Rocks, CO, Montreal, QC, Toronto, ON, Detroit, MI, and an additional date in Washington, DC. You can purchase tickets here. KIDS IN LOVE TOUR PHASE 2 Tuesday, April 10, 2018 - Seattle, WA @ Showare Center Saturday, April 14th, 2018 – Berkeley, CA @ Greek Theatre Wednesday, April 25th, 2018 – Morrison, CO @ Red Rocks Amphitheatre Tuesday, May, 01,2018-