Riches of the Forest: Food, Spices, Crafts and Resins of Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Method to Estimate Dry-Kiln Schedules and Species Groupings: Tropical and Temperate Hardwoods

United States Department of Agriculture Method to Estimate Forest Service Forest Dry-Kiln Schedules Products Laboratory Research and Species Groupings Paper FPL–RP–548 Tropical and Temperate Hardwoods William T. Simpson Abstract Contents Dry-kiln schedules have been developed for many wood Page species. However, one problem is that many, especially tropical species, have no recommended schedule. Another Introduction................................................................1 problem in drying tropical species is the lack of a way to Estimation of Kiln Schedules.........................................1 group them when it is impractical to fill a kiln with a single Background .............................................................1 species. This report investigates the possibility of estimating kiln schedules and grouping species for drying using basic Related Research...................................................1 specific gravity as the primary variable for prediction and grouping. In this study, kiln schedules were estimated by Current Kiln Schedules ..........................................1 establishing least squares relationships between schedule Method of Schedule Estimation...................................2 parameters and basic specific gravity. These relationships were then applied to estimate schedules for 3,237 species Estimation of Initial Conditions ..............................2 from Africa, Asia and Oceana, and Latin America. Nine drying groups were established, based on intervals of specific Estimation -

NATIVE PLANTS for SONG and GAME BIRDS Trees, Shrubs, and Perennials to Attract, Feed, and Provide Habitat for Birds

Promoting Native Plants since 2003 Certified Women Owned Business Enterprise NATIVE PLANTS FOR SONG AND GAME BIRDS Trees, shrubs, and perennials to attract, feed, and provide habitat for birds TREES Botanical Name Common Name Function Acer sp. Maples (red, sugar, striped, & mountain) Cover, Nesting Alnus serrulata Hazel Alder Cover, Nesting Amelanchier canadensis Shadblow Cover, Fruit Amelanchier laevis Allegheny Serviceberry Cover, Fruit Betula sp. Birches (grey, river, yellow, paper, & sweet) Nesting, Seed Carpinus caroliniana American hornbeam Nesting, Seed Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory Nesting, Nuts Carya tomentosa Mockernut Hickory Nesting, Nuts Celtis occidentalis Common Hackberry Cover, Fruit Celtis laevigata Sugarberry Cover, Fruit Chionanthus virginicus Fringe Tree Cover, Fruit Cornus alternifolia Pagoda Dogwood Nesting, Fruit Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Cover, Fruit Crataegus sp. Hawthorns (Washington & green) Nesting, Fruit Euonymus atropurpureus Eastern Wahoo Nesting, Fruit Fagus grandifolia American Beech Cover, Nesting Hamamelis sp. Witchhazels (spring & Virginia) Cover, Seed Ilex opaca American Holly Nesting, Seed Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Cover, Fruit Magnolia sp. Magnolias (sweetbay, cucumber, & umbrella) Cover, Fruit Malus coronaria American Crabapple Nesting, Fruit Picea sp. Spruces (white & red) Cover, Seed Pinus sp. Pines (white, red, pitch, loblolly, shortleaf, & scrub) Cover, Seed Prunus americana American Plum Cover, Fruit Prunus virginiana Chokecherry Cover, Fruit Quercus sp. Oaks (red, black, pin, white, bur, scarlet, & willow) Cover, Acorns Rhus typhina Staghorn Sumac Fruit Salix nigra Black Willow Cover, Nesting Salix discolor Pussy Willow Cover, Buds Sassafras albidum Common Sassafras Cover Sorbus americana American Mountain Ash Cover, Fruit Taxodium distichum Bald Cypress Cover, Seed Tsuga canadensis Canadian Hemlock Cover, Seed Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae Cover, Seed 2415 Route 100 Orefield PA 18069 www.EdgeOfTheWoodsNursery.com SHRUBS & VINES Aronia sp. -

The Herb Society of America Essential Facts for Spicebush Lindera Benzoin

The Herb Society of America Essential Facts for Spicebush Lindera benzoin Family: Lauraceae Latin Name: Lindera benzoin Common Name: spicebush Growth: Perennial shrub, 3 to 9 feet tall, yellow flowers Hardiness: Zone 4b-9a Light: Partial Shade Soil: Rich, acidic to basic soil Water: Mesic, moderately moist Use: Tea, flavoring, medicinal Lindera benzoin fruit Propagation: Seed, clonal via rhizome sprouting, cuttings Photo Wikimedia Commons History Spicebush had multiple medicinal uses Culture In 1783, Carl Peter Thunberg honored by Creek, Cherokee, Rappahannock, Spicebush is primarily an understory Johann Linder (1676-1724), a Swedish Mohegan and Chippewa tribes, who also species found in the wild in open forests botanist and physician, by naming the used the plant to make a beverage and and along forest edges in rich, moder- genus Lindera in honor of him. The to flavor game. It has little commercial ately moist soil and can also be found specific epithetbenzoin is an adaptation value now and can be hard to find in along stream banks. It has a wide grow- of the Middle French benjoin (from nurseries for landscape use. ing range across the country, subject to Arabic luban jawi) literally “Java Frank- winter kill only at the northern extreme incense” and refers to an aromatic of its range. This is an excellent landscape balsamic resin obtained from several Description shrub with multiple season interest. It species of trees in the genus Styrax. In the same family with other aromatic is most spectacular in group plantings shrubs (Laurus nobilis, Cinnamomum The common name for bothLindera spp., Persea spp., and Sassafras spp.) benzoin var. -

A Guide to Medicinal Plants of Appalachia

LACTUCA SCARZOLA L. (ASTERACEAE) COMMON NAMES: Prickly lettuce, compass plant, wild let- tuce, wild opium. DESCRIPTION: An annual or perennial that grows to 2 feet in height. Flowers are yellow, but purple or bluish when dried. Stem has a few prickles. Leaves are cleft, with lobes arranged on either side of a common axis. FLOWERING PERIOD: June to October. HABITAT: Cultivated fields, waste or disturbed areas, dry soil, and gardens. HARVEST: Leaves in summer or fall; milky juice of the stem in summer. USES: The milky juice of this plant is extremely irritating to the eyes. The whole herb has been used as a diuretic, antispasmodic, and emollient. LACTUCA SCARZOLA L. (ASTERACEAE) LEONURUS CARDZACA L. (LAM1ACEAE) COMMON NAMES: Motherwort, common motherwort, lion's ear, lion's tail, lion's tart, throwwort. DESCRIPTION: A perennial that grows to 3 to 6 feet in height. Stems are stout, with 2- to 5-inch long petioled leaves. The palmately lobed leaves have sharp teeth. Flowers are white to pink, and very hairy. FLOWERING PERIOD: May to August. HABITAT: Waste places, roadsides, gardens, and pastures. HARVEST: Herb at flowering time. USES: The herb is used as a stimulant and emmenagogue. In Europe it has been used to treat heart palpitations and asthma. LEONURUS CARDZACA L. (LAMIACEAE) LZNDERA BENZOIN (L.) BLUME (LAURACEAE) COMMON NAMES: Common spicebush, auspice bush, Benja- min bush, feverbush, spiceberry, spicebush, wild allspice. DESCRIPTION: A deciduous shrub that grows to more than, 15 feet in height. Leaves are 3 to 5 inches long, alternate, elliptical, aromatic, with smooth margins. Produces greenish- -yellow flowers in dense clusters and long, bright red berries. -

Organic Commodity Chemicals from Biomass

CHAPTER 13 Organic Commodity Chemicals from Biomass I. INTRODUCTION Biomass is utilized worldwide as a source of many naturally occurring and some synthetic specialty chemicals and cellulosic and starchy polymers. High- value, low-volume products, including many flavorings, drugs, fragrances, dyes, oils, waxes, tannins, resins, gums, rubbers, pesticides, and specialty polymers, are commercially extracted from or produced by conversion of biomass feedstocks. However, biomass conversion to commodity chemicals, which includes the vast majority of commercial organic chemicals, polymers, and plastics, is used to only a limited extent. This was not the case up to the early 1900s. Chars, methanol, acetic acid, acetone, and several pyroligneous chemicals were manufactured by pyrolysis of hardwoods (Chapter 8). The naval stores industry relied upon softwoods as sources of turpentines, terpenes, rosins, pitches, and tars (Chapter 10). The fermentation of sugars and starches supplied large amounts of ethanol, acetone, butanol, and other organic chemi- cals (Chapter 11). Biomass was the primary source of organic chemicals up to the mid- to late 1800s when the fossil fuel era began, and was then gradually displaced by 495 496 Organic Commodity Chemicals from Biomass fossil raw materials as the preferred feedstock for most organic commodities. Aromatic chemicals began to be manufactured in commercial quantities as a by-product of coal coking and pyrolysis processes in the late 1800s. The production of liquid hydrocarbon fuels and organic chemicals by the destruc- tive hydrogenation of coal (Bergius process) began in Germany during World War I. The petrochemical industry started in 1917 when propylene in cracked refinery streams was used to manufacture isopropyl alcohol by direct hydration. -

Flower and Fruit Production of Understory Shrubs in Western Washington and Oregon About This File: This File Was Created by Scanning the Printed Publication

Bryan W. Wender, Constance A. Harrington,1 USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Olympia, Washington 98512-9193 and John C. Tappeiner, II, Department of Forest Resources, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Flower and Fruit Production of Understory Shrubs in Western Washington and Oregon About This File: This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Misscans identified by the software have been corrected; however, some mistakes may remain. Abstract We observed flower and fruit production for nine understory shrub species in western Washington and Oregon and examined the relationships between shrub reproductive output and plant size, plant age, site factors, and overstory density to determine the factors that control flowering or fruiting in understory shrubs. In Washington, 50 or more shrubs or microplots (for rhizomatous species) were sampled for each of eight species. The variables examined were more useful for explaining abundance of flowers or fruit on shrubs than they were for explaining the probability that a shrub would produce flowers or fruit. Plant size was consistently the most useful predictor of flower/fruit abundance in all species; plant age was also a good predictor of abundance and was strongly correlated with plant size. Site variables (e.g., slope) and overstory competition variables (e.g., presence/absence of a canopy gap) also helped explain flower/fruit abundance for some species. At two Oregon sites, the responses of five species to four levels of thinning were observed for 2-4 yr (15± shrubs or microplots per treatment per year). Thinning increased the probability and abundance of flowering/fruiting for two species, had no effect on one species, and responses for two other species were positive but inconsistent between sites or from year to year. -

WO 2016/067138 Al 6 May 2016 (06.05.2016) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/067138 Al 6 May 2016 (06.05.2016) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, A61K 36/00 (2006.01) A23G 4/06 (2006.01) BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, A24B 15/16 (2006.01) DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, (21) International Application Number: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, PCT/IB2015/057766 MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (22) International Filing Date: PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, 10 October 2015 (10.10.201 5) SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (30) Priority Data: GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, 10201407034R 28 October 2014 (28. 10.2014) SG TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, (71) Applicant: R K TECHNOLOGY & INVESTMENTS DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, PTE. -

Read This Article

International Seminar for UNESCO Integral Study of the Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue: “India and the Roman world between 1st and 4th Century A.D.”, “India’s Cultural Relationship with East and Southeast Asia during the 4th to 13th Century A.D.”. 19-24 December 1990. Madras, India. Trade Contacts with the Indonesian Archipelago: 6th to 14th Centuries E. Edwards McKinnon Sea routes from South India and Sri Lanka to the Indonesian islands of Sumatra, Java, Bali, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and beyond appear to have been established by the beginning of the Christian era. Tangible evidence for such contacts appears in the form of Romano-Indian rouletted ware of the first or second centuries A.D. found in the Buni area of West Java (Walker & Santoso 1977) and, more recently, from controlled excavations at Sembiran on the north coast of Bali (Ardika 1989). An early bronze Buddha of Amaravati type from Sulawesi indicates possible connections with Sri Lanka by the c5. Evidence of Indianising influences, from Sanskrit inscriptions written in Tamil Grantha characters of the early/mid fifth century, appears in East Kalimantan and West Java. Monsoons: the crossing of the Oceans. The monsoon winds, which carried ships across the Indian Ocean, blow for six months of the year in one direction and for the other six in the opposite way. Although the changeover periods are somewhat squally, with unsteady winds, the monsoons themselves provide favorable conditions to blow ships from Arabia to China and back. From the end of October to January or February, the northeast monsoon carried ships from Java and Sumatra to Sri Lanka and South India in relatively fine weather. -

Chemical Composition of the Leaf Essential Oil of Lindera Benzoin

American Journal of Essential Oils and Natural Products 2016; 4(3): 01-03 ISSN: 2321 9114 AJEONP 2016; 4(3): 01-03 Chemical composition of the leaf essential oil of Lindera © 2016 AkiNik Publications benzoin growing in North Alabama Received: 01-05-2016 Accepted: 02-06-2016 William N Setzer William N Setzer Department of Chemistry, University of Alabama in Huntsville Abstract Huntsville, AL 35899, USA The leaf essential oil of Lindera benzoin (L.) Blume (Lauraceae), growing in Huntsville, Alabama, was isolated by hydrodistillation. This plant, known commonly as spicebush, was used in native American traditional medicine, and is a host plant of the spicebush swallowtail butterfly, Papilio troilus. The chemical composition of the leaf oil of L. benzoin was determined by GC–MS. The most abundant essential oil components were 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one (42.9%), β-caryophyllene (7.7%), bicyclogermacrene (5.1%), δ-cadinene (4.9%), and (E)-nerolidol (4.8%). Keywords: Lauraceae, host plant, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, sesquiterpenes 1. Introduction Lindera benzoin (L.) Blume var. pubescens (Palmer & Steyermark) Rehd. “northern spicebush”, is a shrub, up to 5 m tall, dioecious. Twigs are olive-green to brown with numerous light lenticels; leaves are alternate, simple, entire, glabrous or pubescent, elliptic to obovate, 7-13 × 2-6 cm, emit a spicy odor when crushed; the bark is brown to gray-brown with light colored lenticels; flowers, in axillary clusters, are small, pale green to yellow; fruit is a bright red oblong drupe, about 10 mm long [1, 2]. L. benzoin ranges in moist forests of eastern North America from southern Ontario to Florida. -

A Art of Essential Oils

The Essence’s of Perfume Materials Glen O. Brechbill FRAGRANCE BOOKS INC. www.perfumerbook.com New Jersey - USA 2009 Fragrance Books Inc. @www.perfumerbook.com GLEN O. BRECHBILL “To my parents & brothers family whose faith in my work & abilities made this manuscript possible” II THE ESSENCES OF PERFUME MATERIALS © This book is a work of non-fiction. No part of the book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Please note the enclosed book is based on The Art of Fragrance Ingredients ©. Designed by Glen O. Brechbill Library of Congress Brechbill, Glen O. The Essence’s of Perfume Materials / Glen O. Brechbill P. cm. 477 pgs. 1. Fragrance Ingredients Non Fiction. 2. Written odor descriptions to facillitate the understanding of the olfactory language. 1. Essential Oils. 2. Aromas. 3. Chemicals. 4. Classification. 5. Source. 6. Art. 7. Thousand’s of fragrances. 8. Science. 9. Creativity. I. Title. Certificate Registry # 1 - 164126868 Copyright © 2009 by Glen O. Brechbill All Rights Reserved PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Fragrance Books Inc. @www.perfumerbook.com THE ESSENCE’S OF PERFUME MATERIALS III My book displays the very best of essential oils. It offers a rich palette of natural ingredients and essences. At its fullest it expresses a passion for the art of perfume. With one hundred seventy-seven listings it condenses a great deal of pertinent information in a single text. -

INCI Terminology

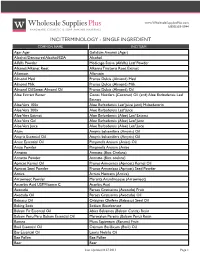

www.WholesaleSuppliesPlus.com 1(800)359-0944 INCI TERMINOLOGY - SINGLE INGREDIENT COMMON NAME INCI TERM Agar Agar Gelidium Amansii (Agar) Alcohol/Denatured Alcohol/SDA Alcohol Alfalfa Powder Medicago Sativa (Alfalfa) Leaf Powder Alkanet/Alkanet Root Alkanna Tinctoria Root Extract Allantoin Allantoin Almond Meal Prunus Dulcis (Almond) Meal Almond Milk Prunus Dulcis (Almond) Milk Almond Oil/Sweet Almond Oil Prunus Dulcis (Almond) Oil Aloe Extract Butter Cocos Nucifera (Coconut) Oil (and) Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Extract Aloe Vera 100x Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Juice (and) Maltodextrin Aloe Vera 200x Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Juice Aloe Vera Extract Aloe Barbadensis (Aloe) Leaf Extract Aloe Vera Gel Aloe Barbadensis (Aloe) Leaf Juice Aloe Vera Juice Aloe Barbadensis (Aloe) Leaf Juice Alum Amyris balsamifera (Amyris) Oil Amyris Essential Oil Amyris balsamifera (Amyris) Oil Anise Essential Oil Pimpinella Anisum (Anise) Oil Anise Powder Pimpinella Anisum (Anise Annatto Annatto (Bixa Orelana) Annatto Powder Annatto (Bixa orelana) Apricot Kernel Oil Prunus Armeniaca (Apricot) Kernel Oil Apricot Seed Powder Prunus Armeniaca (Apricot) Seed Powder Arnica Arnica Montana (Arnica) Arrowroot Powder Maranta Arundinaceae (Arrowroot) Ascorbic Acid USP/Vitamin C Acorbic Acid Avocado Persea Gratissima (Avocado) Fruit Avocado Oil Persea Gratissima (Avocado) Oil Babassu Oil Orbignya Oleifera (Babassu) Seed Oil Baking Soda Sodium Bicarbonate Balsam Fir Essential Oil Abies Balsamea (Balsam Canda) Resin Balsam Peru/Peru Balsam Essential Oil Myroxylon Pereira (Balsam Peru) -

Rasayana: Ayurvedic Herbs for Longevity and Rejuvenation

Rasayana Traditional Herbal Medicines for Modern Times Each volume in this series provides academia, health sciences and the herbal medicines industry with in-depth coverage of the herbal remedies for infectious diseases, certain medical conditions or the plant medicines of a particular country. Edited by Dr Roland Hardman Volume 1 Shengmai San, edited by Kam-Ming Ko Volume 2 Rasayana, by H.S. Puri Rasayana Ayurvedic herbs for longevity and rejuvenation H.S. Puri First published 2003 by Taylor & Francis 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Taylor & Francis Inc, 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Taylor & Francis is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 2003 Taylor & Francis All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Every effort has been made to ensure that the advice and information in this book is true and accurate at the time of going to press. However, neither the publisher nor the authors can accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. In the case of drug administration, any medical procedure or the use of technical equipment mentioned within this book, you are strongly advised to consult the