Bending and Unbending of Tools by New Caledonian Crows (Corvus Moneduloides) in a Problem-Solving Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intelligence in Corvids and Apes: a Case of Convergent Evolution? Amanda Seed*, Nathan Emery & Nicola Claytonà

Ethology CURRENT ISSUES – PERSPECTIVES AND REVIEWS Intelligence in Corvids and Apes: A Case of Convergent Evolution? Amanda Seed*, Nathan Emery & Nicola Claytonà * Department of Psychology, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany School of Biological & Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK à Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (Invited Review) Correspondence Abstract Nicola Clayton, Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge, Downing Intelligence is suggested to have evolved in primates in response to com- Street, Cambridge CB23EB, UK. plexities in the environment faced by their ancestors. Corvids, a large- E-mail: [email protected] brained group of birds, have been suggested to have undergone a con- vergent evolution of intelligence [Emery & Clayton (2004) Science, Vol. Received: November 13, 2008 306, pp. 1903–1907]. Here we review evidence for the proposal from Initial acceptance: December 26, 2008 both ultimate and proximate perspectives. While we show that many of Final acceptance: February 15, 2009 (M. Taborsky) the proposed hypotheses for the evolutionary origin of great ape intelli- gence also apply to corvids, further study is needed to reveal the selec- doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2009.01644.x tive pressures that resulted in the evolution of intelligent behaviour in both corvids and apes. For comparative proximate analyses we empha- size the need to be explicit about the level of analysis to reveal the type of convergence that has taken place. Although there is evidence that corvids and apes solve social and physical problems with similar speed and flexibility, there is a great deal more to be learned about the repre- sentations and algorithms underpinning these computations in both groups. -

Why Preen Others? Predictors of Allopreening in Parrots and Corvids and Comparisons to 2 Grooming in Great Apes

1 Why preen others? Predictors of allopreening in parrots and corvids and comparisons to 2 grooming in great apes 3 Short running title: Allopreening in parrots and corvids 4 Alejandra Morales Picard1,2, Roger Mundry3,4, Alice M. Auersperg3, Emily R. Boeving5, 5 Palmyre H. Boucherie6,7, Thomas Bugnyar8, Valérie Dufour9, Nathan J. Emery10, Ira G. 6 Federspiel8,11, Gyula K. Gajdon3, Jean-Pascal Guéry12, Matjaž Hegedič8, Lisa Horn8, Eithne 7 Kavanagh1, Megan L. Lambert1,3, Jorg J. M. Massen8,13, Michelle A. Rodrigues14, Martina 8 Schiestl15, Raoul Schwing3, Birgit Szabo8,16, Alex H. Taylor15, Jayden O. van Horik17, Auguste 9 M. P. von Bayern18, Amanda Seed19, Katie E. Slocombe1 10 1Department of Psychology, University of York, UK 11 2Montgomery College, Rockville, Maryland, USA 12 3Messerli Research Institute, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Medical University 13 Vienna, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. 14 4Platform Bioinformatics and Biostatistics, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Austria. 15 5Department of Psychology, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA 16 6Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien, University of Strasbourg, 23 rue Becquerel 67087 17 Strasbourg, France 18 7Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UMR 7178, 67087 Strasbourg, France 19 8Department of Cognitive Biology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria 20 9UMR Physiologie de la Reproduction et des Comportements, INRA-CNRS-Université de Tours 21 -IFCE, 37380 Nouzilly, France 22 10School of Biological & Chemical Sciences, Queen -

At Natural Foraging Sites Corvus Moneduloides Tool Use by Wild New Caledonian Crows

Downloaded from rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org on January 30, 2014 Tool use by wild New Caledonian crows Corvus moneduloides at natural foraging sites Lucas A. Bluff, Jolyon Troscianko, Alex A. S. Weir, Alex Kacelnik and Christian Rutz Proc. R. Soc. B 2010 277, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1953 first published online 6 January 2010 Supplementary data "Data Supplement" http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/suppl/2010/01/05/rspb.2009.1953.DC1.h tml References This article cites 23 articles, 5 of which can be accessed free http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/277/1686/1377.full.html#ref-list-1 Article cited in: http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/277/1686/1377.full.html#related-urls Subject collections Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections behaviour (1094 articles) Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article - sign up in the box at the top Email alerting service right-hand corner of the article or click here To subscribe to Proc. R. Soc. B go to: http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/subscriptions Downloaded from rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org on January 30, 2014 Proc. R. Soc. B (2010) 277, 1377–1385 doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1953 Published online 6 January 2010 Tool use by wild New Caledonian crows Corvus moneduloides at natural foraging sites Lucas A. Bluff1,*,†,‡, Jolyon Troscianko2, Alex A. S. Weir1, Alex Kacelnik1 and Christian Rutz1,*,‡ 1Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK 2School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK New Caledonian crows Corvus moneduloides use tools made from sticks or leaf stems to ‘fish’ woodboring beetle larvae from their burrows in decaying wood. -

Individual Repeatability, Species Differences, and The

Supplementary Materials: Individual repeatability, species differences, and the influence of socio-ecological factors on neophobia in 10 corvid species SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS 2 Figure S1 . Latency to touch familiar food in each round, across all conditions and species. Round 3 differs from round 1 and 2, while round 1 and 2 do not differ from each other. Points represent individuals, lines represent median. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS 3 Figure S2 . Site effect on latency to touch familiar food in azure-winged magpie, carrion crow and pinyon jay. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS 4 Table S1 Pairwise comparisons of latency data between species Estimate Standard error z p-value Blue jay - Azure-winged magpie 0.491 0.209 2.351 0.019 Carrion crow - Azure-winged magpie -0.496 0.177 -2.811 0.005 Clark’s nutcracker - Azure-winged magpie 0.518 0.203 2.558 0.011 Common raven - Azure-winged magpie -0.437 0.183 -2.392 0.017 Eurasian jay - Azure-winged magpie 0.284 0.166 1.710 0.087 ’Alal¯a- Azure-winged magpie 0.416 0.144 2.891 0.004 Large-billed crow - Azure-winged magpie 0.668 0.189 3.540 0.000 New Caledonian crow - Azure-winged magpie -0.316 0.209 -1.513 0.130 Pinyon jay - Azure-winged magpie 0.118 0.170 0.693 0.488 Carrion crow - Blue jay -0.988 0.199 -4.959 0.000 Clark’s nutcracker - Blue jay 0.027 0.223 0.122 0.903 Common raven - Blue jay -0.929 0.205 -4.537 0.000 Eurasian jay - Blue jay -0.207 0.190 -1.091 0.275 ’Alal¯a- Blue jay -0.076 0.171 -0.443 0.658 Large-billed crow - Blue jay 0.177 0.210 0.843 0.399 New Caledonian crow - Blue jay -0.808 0.228 -3.536 -

Adaptive Bill Morphology for Enhanced Tool Manipulation in New Caledonian Crows Received: 30 November 2015 Hiroshi Matsui1,*, Gavin R

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Adaptive bill morphology for enhanced tool manipulation in New Caledonian crows Received: 30 November 2015 Hiroshi Matsui1,*, Gavin R. Hunt2,*, Katja Oberhofer3, Naomichi Ogihara4, Kevin J. McGowan5, Accepted: 19 February 2016 Kumar Mithraratne3, Takeshi Yamasaki6, Russell D. Gray2,7 & Ei-Ichi Izawa1 Published: 09 March 2016 Early increased sophistication of human tools is thought to be underpinned by adaptive morphology for efficient tool manipulation. Such adaptive specialisation is unknown in nonhuman primates but may have evolved in the New Caledonian crow, which has sophisticated tool manufacture. The straightness of its bill, for example, may be adaptive for enhanced visually-directed use of tools. Here, we examine in detail the shape and internal structure of the New Caledonian crow’s bill using Principal Components Analysis and Computed Tomography within a comparative framework. We found that the bill has a combination of interrelated shape and structural features unique within Corvus, and possibly birds generally. The upper mandible is relatively deep and short with a straight cutting edge, and the lower mandible is strengthened and upturned. These novel combined attributes would be functional for (i) counteracting the unique loading patterns acting on the bill when manipulating tools, (ii) a strong precision grip to hold tools securely, and (iii) enhanced visually-guided tool use. Our findings indicate that the New Caledonian crow’s innovative bill has been adapted for tool manipulation to at least some degree. Early increased sophistication of tools may require the co-evolution of morphology that provides improved manipulatory skills. Human tool behaviour is underpinned by adaptations associated with enhanced manipulation of tools and tool material. -

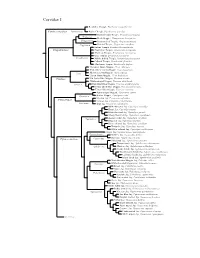

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Age-Related Differences in Diet and Foraging Behavior of the Critically Endangered Mariana Crow

Age-related differences in diet and foraging behavior of the critically endangered Mariana Crow (Corvus kubaryi) Sarah K. Faegre A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science University of Washington 2014 Committee: Renee Robinette Ha Michael Beecher Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Psychology ©Copyright 2014 Sarah K. Faegre University of Washington Abstract Age-related differences in diet and foraging behavior of the critically endangered Mariana Crow (Corvus kubaryi) Sarah K. Faegre Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Renee Robinette Ha Psychology The Mariana Crow (Corvus kubaryi) is a critically endangered, island-endemic corvid whose single remaining population is on the island of Rota, CNMI. Quantitative information on the Mariana Crow’s diet is lacking and the effects of age and season on diet and foraging behavior are unknown. Most corvids are social omnivores that typically learn from adults to master complex foraging behaviors. We hypothesized that age-related differences in the diets and foraging behaviors of Mariana Crows would occur due to both a period of physical maturation and steps in learning. This study identified 619 food items taken by 36 wild crows and determined the corresponding foraging strata and substrates for 469 and 363 items respectively. Fourteen percent of food captures were plant-based and 86% were animal prey; 65% of animal prey were insects or their larvae and eggs. The study also identified 209 food items, and their corresponding forest strata and substrates, taken by two captive-reared crows during the first eleven months post-release. Comparisons of the foraging behaviors and diets of captive-reared and wild crows indicated that the released crows foraged on all important prey types taken by wild crows; however, several differences in food category proportions were noted. -

UK-First-Breeding-Register.Pdf

INTRODUCTION TO EDITION The original author and compiler of this record, Dave Coles has devoted a great deal of his time in creating a unique reference document which I am privileged to continue working with. By its very nature the document in a living project which will continue to grow and evolve and I can only hope and wish that I have the dedication as Dave has had in ensuring the continuity of the “First Breeding Register”. Initially all my additions and edits will be indicated in italics though this will not be used in the main body of the record (when a new record is added). Simon Matthews (2011) It is over eighty years since Emilius Hopkinson collated his RECORDS OF BIRDS BRED IN CAPTIVITY, which formed the starting point for my attempt at recording first breeding records for the UK. Since the first edition of my records was published in 1986, classification has changed several times and the present edition incorporates this up-dated classification as well as first breeding recorded since then. The research needed to produce the original volume took many years to complete and covered most avicultural literature. Since that time numerous people have kept me abreast of further breedings and pointing out those that have slipped the net. This has hopefully enabled the records to be kept up-to- date. To those I would express my thanks as indeed I do to all that have cast their eyes over the new list and passed comments, especially the ever helpful Reuben Girling who continues to pass on enquiries. -

Do New Caledonian Crows Solve Physical Problems Through Causal Reasoning? A

Proc. R. Soc. B (2009) 276, 247–254 doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1107 Published online 16 September 2008 Do New Caledonian crows solve physical problems through causal reasoning? A. H. Taylor*, G. R. Hunt, F. S. Medina and R. D. Gray* Department of Psychology, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand The extent to which animals other than humans can reason about physical problems is contentious. The benchmark test for this ability has been the trap-tube task. We presented New Caledonian crows with a series of two-trap versions of this problem. Three out of six crows solved the initial trap-tube. These crows continued to avoid the trap when the arbitrary features that had previously been associated with successful performances were removed. However, they did not avoid the trap when a hole and a functional trap were in the tube. In contrast to a recent primate study, the three crows then solved a causally equivalent but visually distinct problem—the trap-table task. The performance of the three crows across the four transfers made explanations based on chance, associative learning, visual and tactile generalization, and previous dispositions unlikely. Our findings suggest that New Caledonian crows can solve complex physical problems by reasoning both causally and analogically about causal relations. Causal and analogical reasoning may form the basis of the New Caledonian crow’s exceptional tool skills. Keywords: New Caledonian crows; causal reasoning; analogical reasoning; trap tube; trap table 1. INTRODUCTION that non-human animals use sophisticated cognition when The eighteenth century philosopher David Hume solving complex physical problems has led to suggestions (1711–1776) famously used the example of one billiard that causal reasoning in humans is fundamentally different ball rolling into another to illustrate his argument that (Penn & Povinelli 2007; Penn et al. -

And Socio-Ecology of Wild Goffin's Cockatoos (Cacatua Goffiniana)

Behaviour 156 (2019) 661–690 brill.com/beh Extraction without tooling around — The first comprehensive description of the foraging- and socio-ecology of wild Goffin’s cockatoos (Cacatua goffiniana) M. O’Hara a,∗, B. Mioduszewska a,b, T. Haryoko c, D.M. Prawiradilaga c, L. Huber a and A. Auersperg a a Comparative Cognition, Messerli Research Institute, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Medical University Vienna, University of Vienna, Veterinaerplatz 1, 1210 Vienna, Austria b Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, Eberhard-Gwinner-Straße, 82319 Seewiesen, Germany c Research Center for Biology, Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Jl. Raya Jakarta - Bogor Km.46 Cibinong 16911 Bogor, Indonesia *Corresponding author’s e-mail address: [email protected] Received 7 June 2018; initial decision 14 August 2018; revised 8 October 2018; accepted 9 October 2018; published online 24 October 2018 Abstract When tested under laboratory conditions, Goffin’s cockatoos (Cacatua goffiniana) demonstrate numerous sophisticated cognitive skills. Most importantly, this species has shown the ability to manufacture and use tools. However, little is known about the ecology of these cockatoos, en- demic to the Tanimbar Islands in Indonesia. Here we provide first insights into the feeding- and socio-ecology of the wild Goffin’s cockatoos and propose potential links between their behaviour in natural settings and their advanced problem-solving capacities shown in captivity. Observational data suggests that Goffin’s cockatoos rely on a large variety of partially seasonal resources. Further- more, several food types require different extraction techniques. These ecological and behavioural characteristics fall in line with current hypotheses regarding the evolution of complex cognition and innovativeness. -

Ringing & Migration

Ringing & Migration VOLUME 24 2008 and 2009 Editor Chris Redfern Managing Editor Jacquie Clark Copy Editor John Marchant Editorial Board 2008 & 2009 Guy Anderson, Franz Bairlein, Jon Coleman, Jennifer Gill, Hugh Insley, Åke Lindström, Stephen Norman, Jane Reid, Roger Riddington and Graham Scott ISSN 0307-8698 Vol 24 Contents Ringing & Migration Contents of Vol 24, 2008 and 2009 Part 1 (June 2008) FULL PAPER Survival rates of hirundines in relation to British and African rainfall. Robert A. Robinson, Dawn E. Balmer and John H. Marchant ....................................................................................................................................................................................1 SHORT REPORTS From fledging to breeding: long-term satellite tracking of the migratory behaviour of a Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus intermedius. K. Pütz, A.J. Helbig, K.T. Pedersen, C. Rahbek, P. Saurola and R. Juvaste ....................................................7 On reading colour rings. Carl Mitchell and Mark Trinder.......................................................................................................................11 RINGING SCHEME REPORT Bird ringing in Britain and Ireland in 2006. Liz Coiffait, Jacquie A. Clark, Robert A. Robinson, Jeremy R. Blackburn, Bridget M. Griffin, Kate Risely, Mark J. Grantham, John H. Marchant, Trevor Girling and Lee Barber ..........................................15 Part 2 (December 2008) FULL PAPERS Sexual size dimorphism and moult in the Plain Swift Apus unicolor. -

Weir Thesis.Pdf

Cognitive psychology of tool use in New Caledonian crows (Corvus moneduloides ) Alexander Allan Scott Weir Magdalen College and Department of Zoology University of Oxford Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Trinity Term 2005 Cognitive psychology of tool use in New Caledonian crows (Corvus moneduloides ) Alexander Allan Scott Weir, Magdalen College and Department of Zoology Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Trinity Term, 2005 ABSTRACT Most studies into the evolution of humans’ manufacture and use of tools have concentrated on non-human primates. Within the past decade, however, it has been reported that wild New Caledonian crows make and use tools as complex as those of chimpanzees, and that aspects of their behaviour may be culturally transmitted. In this thesis, I present work examining the cognitive basis of New Caledonian crows’ tool-oriented behaviour. I begin by reviewing the hotly-disputed issue of whether non-human animals are capable of ‘reasoning’ in the physical domain, and examining experiments designed to address this issue. It has often been claimed that naturally-occurring tool use and manufacture indicates special cognitive abilities, so I critically analyse this argument and propose a framework that might allow the question to be tested empirically. After reviewing what is known of the ecology of New Caledonian crows, I address cognition directly, presenting results from two studies into their understanding of hooks and tool shape. I report that one subject showed remarkable innovation and flexibility by spontaneously making hooks out of wire when she needed a hooked tool, and by quickly transferring this ability to novel material requiring a different technique.