Why Preen Others? Predictors of Allopreening in Parrots and Corvids and Comparisons to 2 Grooming in Great Apes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Behavior and Attendance Patterns of the Fork-Tailed Storm-Petrel

BEHAVIOR AND ATTENDANCE PATTERNS OF THE FORK-TAILED STORM-PETREL THEODORE R. SIMONS Wildlife Science Group, Collegeof Forest Resources, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 USA ABSTRACT.--Behavior and attendance patterns of breeding Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels (Ocea- nodromafurcata) were monitored over two nesting seasonson the Barren Islands, Alaska. The asynchrony of egg laying and hatching shown by these birds apparently reflects the influence of severalfactors, including snow conditionson the breedinggrounds, egg neglectduring incubation, and food availability. Communication between breeding birds was characterized by auditory and tactile signals.Two distinct vocalizationswere identified, one of which appearsto be a sex-specific call given by males during pair formation. Generally, both adults were present in the burrow on the night of egg laying, and the male took the first incubation shift. Incubation shiftsranged from 1 to 5 days, with 2- and 3-day shifts being the most common. Growth parameters of the chicks, reproductive success, and breeding chronology varied considerably between years; this pre- sumably relates to a difference in conditions affecting the availability of food. Adults apparently responded to changes in food availability during incubation by altering their attendance patterns. When conditionswere good, incubation shifts were shorter, egg neglectwas reduced, and chicks were brooded longer and were fed more frequently. Adults assistedthe chick in emerging from the shell. Chicks became active late in the nestling stage and began to venture from the burrow severaldays prior to fledging. Adults continuedto visit the chick during that time but may have reducedthe amountof fooddelivered. Chicks exhibiteda distinctprefledging weight loss.Received 18 September1979, accepted26 July 1980. -

Natural History and Breeding Behavior of the Tinamou, Nothoprocta Ornata

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VoL. 72 APRIL, 1955 No. 2 NATURAL HISTORY AND BREEDING BEHAVIOR OF THE TINAMOU, NOTHOPROCTA ORNATA ON the high mountainous plain of southern Peril west of Lake Titicaca live three speciesof the little known family Tinamidae. The three speciesrepresent three different genera and grade in size from the small, quail-sizedNothura darwini found in the farin land and grassy hills about Lake Titicaca between 12,500 and 13,300 feet to the large, pheasant-sized Tinamotis pentlandi in the bleak country between 14,000 and 16,000 feet. Nothoproctaornata, the third species in this area and the one to be discussedin the present report, is in- termediate in size and generally occurs at intermediate elevations. In Peril we have encountered Nothoproctabetween 13,000 and 14,300 feet. It often lives in the same grassy areas as Nothura; indeed, the two speciesmay be flushed simultaneouslyfrom the same spot. This is not true of Nothoproctaand the larger tinamou, Tinamotis, for although at places they occur within a few hundred yards of each other, Nothoproctais usually found in the bunch grassknown locally as ichu (mostly Stipa ichu) or in a mixture of ichu and tola shrubs, whereas Tinamotis usually occurs in the range of a different bunch grass, Festuca orthophylla. The three speciesof tinamous are dis- tinguished by the inhabitants, some of whom refer to Nothura as "codorniz" and to Nothoproctaas "perdiz." Tinamotis is always called "quivia," "quello," "keu," or some similar derivative of its distinctive call. The hilly, almost treeless countryside in which Nothoproctalives in southern Peril is used primarily for grazing sheep, alpacas,llamas, and cattle. -

Intelligence in Corvids and Apes: a Case of Convergent Evolution? Amanda Seed*, Nathan Emery & Nicola Claytonà

Ethology CURRENT ISSUES – PERSPECTIVES AND REVIEWS Intelligence in Corvids and Apes: A Case of Convergent Evolution? Amanda Seed*, Nathan Emery & Nicola Claytonà * Department of Psychology, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany School of Biological & Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK à Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (Invited Review) Correspondence Abstract Nicola Clayton, Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge, Downing Intelligence is suggested to have evolved in primates in response to com- Street, Cambridge CB23EB, UK. plexities in the environment faced by their ancestors. Corvids, a large- E-mail: [email protected] brained group of birds, have been suggested to have undergone a con- vergent evolution of intelligence [Emery & Clayton (2004) Science, Vol. Received: November 13, 2008 306, pp. 1903–1907]. Here we review evidence for the proposal from Initial acceptance: December 26, 2008 both ultimate and proximate perspectives. While we show that many of Final acceptance: February 15, 2009 (M. Taborsky) the proposed hypotheses for the evolutionary origin of great ape intelli- gence also apply to corvids, further study is needed to reveal the selec- doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2009.01644.x tive pressures that resulted in the evolution of intelligent behaviour in both corvids and apes. For comparative proximate analyses we empha- size the need to be explicit about the level of analysis to reveal the type of convergence that has taken place. Although there is evidence that corvids and apes solve social and physical problems with similar speed and flexibility, there is a great deal more to be learned about the repre- sentations and algorithms underpinning these computations in both groups. -

Uropygial Gland in Birds

UROPYGIAL GLAND IN BIRDS Prepared by Dr. Subhadeep Sarker Associate Professor, Department of Zoology, Serampore College Occurrence and Location: • The uropygial gland, often referred to as the oil or preen gland, is a bilobed gland and is found at the dorsal base of the tail of most psittacine birds. • The uropygial gland is a median dorsal gland, one per bird, in the synsacro-caudal region. A half moon-shaped row of feather follicles of the upper median and major tail coverts externally outline its position. • The uropygial area is located dorsally over the pygostyle on the midline at the base of the tail. • This gland is most developed in waterfowl but very reduced or even absent in many parrots (e.g. Amazon parrots), ostriches and many pigeons and doves. Anatomy: • The uropygial gland is an epidermal bilobed holocrine gland localized on the uropygium of most birds. • It is composed of two lobes separated by an interlobular septum and covered by an external capsule. • Uropygial secretory tissue is housed within the lobes of the gland (Lobus glandulae uropygialis), which are nearly always two in number. Exceptions occur in Hoopoe (Upupa epops) with three lobes, and owls with one. Duct and cavity systems are also contained within the lobes. • The architectural patterns formed by the secretory tubules, the cavities and ducts, differ markedly among species. The primary cavity can comprise over 90% of lobe volume in the Oilbird (Steatornis caripensis) and some woodpeckers and pigeons. • The gland is covered by a circlet or tuft of down feathers called the uropygial wick in many birds. -

At Natural Foraging Sites Corvus Moneduloides Tool Use by Wild New Caledonian Crows

Downloaded from rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org on January 30, 2014 Tool use by wild New Caledonian crows Corvus moneduloides at natural foraging sites Lucas A. Bluff, Jolyon Troscianko, Alex A. S. Weir, Alex Kacelnik and Christian Rutz Proc. R. Soc. B 2010 277, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1953 first published online 6 January 2010 Supplementary data "Data Supplement" http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/suppl/2010/01/05/rspb.2009.1953.DC1.h tml References This article cites 23 articles, 5 of which can be accessed free http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/277/1686/1377.full.html#ref-list-1 Article cited in: http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/277/1686/1377.full.html#related-urls Subject collections Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections behaviour (1094 articles) Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article - sign up in the box at the top Email alerting service right-hand corner of the article or click here To subscribe to Proc. R. Soc. B go to: http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/subscriptions Downloaded from rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org on January 30, 2014 Proc. R. Soc. B (2010) 277, 1377–1385 doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1953 Published online 6 January 2010 Tool use by wild New Caledonian crows Corvus moneduloides at natural foraging sites Lucas A. Bluff1,*,†,‡, Jolyon Troscianko2, Alex A. S. Weir1, Alex Kacelnik1 and Christian Rutz1,*,‡ 1Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK 2School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK New Caledonian crows Corvus moneduloides use tools made from sticks or leaf stems to ‘fish’ woodboring beetle larvae from their burrows in decaying wood. -

Individual Repeatability, Species Differences, and The

Supplementary Materials: Individual repeatability, species differences, and the influence of socio-ecological factors on neophobia in 10 corvid species SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS 2 Figure S1 . Latency to touch familiar food in each round, across all conditions and species. Round 3 differs from round 1 and 2, while round 1 and 2 do not differ from each other. Points represent individuals, lines represent median. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS 3 Figure S2 . Site effect on latency to touch familiar food in azure-winged magpie, carrion crow and pinyon jay. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS 4 Table S1 Pairwise comparisons of latency data between species Estimate Standard error z p-value Blue jay - Azure-winged magpie 0.491 0.209 2.351 0.019 Carrion crow - Azure-winged magpie -0.496 0.177 -2.811 0.005 Clark’s nutcracker - Azure-winged magpie 0.518 0.203 2.558 0.011 Common raven - Azure-winged magpie -0.437 0.183 -2.392 0.017 Eurasian jay - Azure-winged magpie 0.284 0.166 1.710 0.087 ’Alal¯a- Azure-winged magpie 0.416 0.144 2.891 0.004 Large-billed crow - Azure-winged magpie 0.668 0.189 3.540 0.000 New Caledonian crow - Azure-winged magpie -0.316 0.209 -1.513 0.130 Pinyon jay - Azure-winged magpie 0.118 0.170 0.693 0.488 Carrion crow - Blue jay -0.988 0.199 -4.959 0.000 Clark’s nutcracker - Blue jay 0.027 0.223 0.122 0.903 Common raven - Blue jay -0.929 0.205 -4.537 0.000 Eurasian jay - Blue jay -0.207 0.190 -1.091 0.275 ’Alal¯a- Blue jay -0.076 0.171 -0.443 0.658 Large-billed crow - Blue jay 0.177 0.210 0.843 0.399 New Caledonian crow - Blue jay -0.808 0.228 -3.536 -

Feather Destructive Behaviour

FEATHER DESTRUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR Feather destructive behaviour (FDB) is a common presentation in pet and aviary birds, although it is not usually seen in their wild counterparts. It often has a multi-factorial aetiology, and can be a complex and challenging condition to treat. This article will give an outline of the potential causes of FDB and suggests an approach to its investigation and management in pet parrots. What is FDB? Birds are unique amongst the animal kingdom in possessing feathers. Feathers have a number of functions; providing a means for flight, being involved in thermoregulation, and acting as a means of communication, especially for reproductive purposes. FDB occurs when a bird plucks out or damages its feathers. It may progress from feather picking, where a bird may just chew on its feathers, to a more severe form that involves self-trauma to the skin or underlying structures. Why do birds pick their feathers? The causes of FDB can be divided into two main categories: medical and behavioural. Stress, in some form, is often part of the cause. It is important to investigate and rule out medical causes of FDB before considering a behavioural aetiology. Medical causes of FDB may directly relate to the skin and feathers, or may relate to stressors from a primary disease process elsewhere in the body. Factors such as an inadequate diet, infection (bacterial/viral/fungal/parasitic), access or exposure to toxins or allergens, and internal metabolic or endocrine disease may all result in birds displaying FDB and/or self- mutilating. In some birds mild irritation from over-preening moulting feathers may trigger an itch-chew cycle and progress to FDB. -

Comparative Preening Behavior of Wild-Caught Canada Geese and Mallards.- Comfort Movements Have Been Described for Many Birds (C.F., Goodwin, Br

690 THE WILSON BULLETIN - Vol. 95, No. 4, December 1983 of winter above that in the preceding spring, depending upon over-all productivity, mortality in other habitats and wintering areas, and other factors. It is impossible for a single team of observers to adequately census all habitats in a region within the time limitations required, but studies that do not cover all of the habitats used by the winter species are likely to be misleading on questions of population change during the season. Habitat availability must also be considered in such studies, but data on availability of even gross (vs micro) habitat types are generally lacking. Two patterns that seem clear from this and our previous (1979) study is that notable declines occur over winter in natural habitats in mild as well as in severe winters, and that the steepness of the decline is related especially to the size of the starting population. The observation that bird populations declined through the winter in both mild and severe winters is important to those who census winter birds. The seasonal limits designated for Audubon winter bird studies is 20 December-10 February (Robbins, Studies in Avian Biology 6:52-57, 1981). The results would differ according to the pattern of censusing in that period- early censuses indicating high populations, later censuses lower populations. Fortunately the dates of censuses are usually presented, but the rules of censusing may need to be more precisely delineated, as Robhins (1981) has suggested. Acknowledgments.-We are indebted to Richard E. Warner and Glen C. Sanderson of the Illinois Natural History Survey for helpful suggestions on the original manuscript.-JEAN W. -

Molecular Ecology of Petrels

M o le c u la r e c o lo g y o f p e tr e ls (P te r o d r o m a sp p .) fr o m th e In d ia n O c e a n a n d N E A tla n tic , a n d im p lic a tio n s fo r th e ir c o n se r v a tio n m a n a g e m e n t. R u th M a rg a re t B ro w n A th e sis p re se n te d fo r th e d e g re e o f D o c to r o f P h ilo so p h y . S c h o o l o f B io lo g ic a l a n d C h e m ic a l S c ie n c e s, Q u e e n M a ry , U n iv e rsity o f L o n d o n . a n d In stitu te o f Z o o lo g y , Z o o lo g ic a l S o c ie ty o f L o n d o n . A u g u st 2 0 0 8 Statement of Originality I certify that this thesis, and the research to which it refers, are the product of my own work, and that any ideas or quotations from the work of other people, published or otherwise, are fully acknowledged in accordance with the standard referencing practices of the discipline. -

Adaptive Bill Morphology for Enhanced Tool Manipulation in New Caledonian Crows Received: 30 November 2015 Hiroshi Matsui1,*, Gavin R

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Adaptive bill morphology for enhanced tool manipulation in New Caledonian crows Received: 30 November 2015 Hiroshi Matsui1,*, Gavin R. Hunt2,*, Katja Oberhofer3, Naomichi Ogihara4, Kevin J. McGowan5, Accepted: 19 February 2016 Kumar Mithraratne3, Takeshi Yamasaki6, Russell D. Gray2,7 & Ei-Ichi Izawa1 Published: 09 March 2016 Early increased sophistication of human tools is thought to be underpinned by adaptive morphology for efficient tool manipulation. Such adaptive specialisation is unknown in nonhuman primates but may have evolved in the New Caledonian crow, which has sophisticated tool manufacture. The straightness of its bill, for example, may be adaptive for enhanced visually-directed use of tools. Here, we examine in detail the shape and internal structure of the New Caledonian crow’s bill using Principal Components Analysis and Computed Tomography within a comparative framework. We found that the bill has a combination of interrelated shape and structural features unique within Corvus, and possibly birds generally. The upper mandible is relatively deep and short with a straight cutting edge, and the lower mandible is strengthened and upturned. These novel combined attributes would be functional for (i) counteracting the unique loading patterns acting on the bill when manipulating tools, (ii) a strong precision grip to hold tools securely, and (iii) enhanced visually-guided tool use. Our findings indicate that the New Caledonian crow’s innovative bill has been adapted for tool manipulation to at least some degree. Early increased sophistication of tools may require the co-evolution of morphology that provides improved manipulatory skills. Human tool behaviour is underpinned by adaptations associated with enhanced manipulation of tools and tool material. -

Birds and Mammals)

6-3.1 Compare the characteristic structures of invertebrate animals... and vertebrate animals (...birds and mammals). Also covers: 6-1.1, 6-1.2, 6-1.5, 6-3.2, 6-3.3 Birds and Mammals sections More Alike than Not! Birds and mammals have adaptations that 1 Birds allow them to live on every continent and in 2 Mammals every ocean. Some of these animals have Lab Mammal Footprints adapted to withstand the coldest or hottest Lab Bird Counts conditions. These adaptations help to make Virtual Lab How are birds these animal groups successful. adapted to their habitat? Science Journal List similar characteristics of a mammal and a bird. What characteristics are different? 254 Theo Allofs/CORBIS Start-Up Activities Birds and Mammals Make the following Foldable to help you organize information about the Bird Gizzards behaviors of birds and mammals. You may have observed a variety of animals in your neighborhood. Maybe you have STEP 1 Fold one piece of paper widthwise into thirds. watched birds at a bird feeder. Birds don’t chew their food because they don’t have teeth. Instead, many birds swallow small pebbles, bits of eggshells, and other hard materials that go into the gizzard—a mus- STEP 2 Fold down 2.5 cm cular digestive organ. Inside the gizzard, they from the top. (Hint: help grind up the seeds. The lab below mod- From the tip of your els the action of a gizzard. index finger to your middle knuckle is about 2.5 cm.) 1. Place some cracked corn, sunflower seeds, nuts or other seeds, and some gravel in an STEP 3 Fold the rest into fifths. -

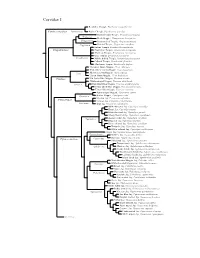

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus