Starlings and Mynas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

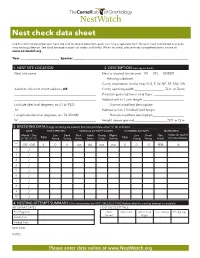

Nest Check Data Sheet

Nest check data sheet Use this form to describe your nest site and to record data from each visit. Use a separate form for each nest monitored and each new nesting attempt. See back for explanations of codes and fields. When finished, please enter completed forms online at: www.nestwatch.org. Year _________________________ Species ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. NEST SITE LOCATION 2. DESCRIPTION (see key on back) Nest site name Nest is located (circle one) IN ON UNDER __________________________________________________ Nesting substrate _______________________________ Cavity orientation (circle one) N, S, E, W, NE, SE, NW, SW Address: Nearest street address OR Cavity opening width __________________ ❏ in. or ❏ cm __________________________________________________ Predator guard ❏ None or ❏ Type: __________________ __________________________________________________ Habitat within 1 arm length _________________________ Latitude (decimal degrees; ex 47.67932) Human modified description ___________________ N _______________________________________________ Habitat within 1 football field length _________________ Longitude (decimal degrees; ex -76.45448) Human modified description ___________________ W _______________________________________________ Height above ground ____________________❏ ft. or ❏ m 3. BREEDING DATA If eggs or young are present but not countable, enter “u” for unknown. DATE HOST SPECIES STATUS & ACTIVITY CODES COWBIRD ACTIVITY MORE INFO Month / Day Live Dead Nest Adult Young -

FIRST CONTROL CAMPAIGN for COMMON MYNA (Acridotheres

FIRST CONTROL CAMPAIGN FOR COMMON MYNA ( Acridotheres tristis ) ON ASCENSION ISLAND 2009 By Susana Saavedra Project and field manager 1 Abstract This is a final report of the “First control campaign for Common myna (Acridotheres tristis ) in Ascension Island 2009”, which was undertaken as a private initiative of Live Arico Invasive Species Department. The field work took place, from the 25 th of September to 03 rd December 2009. Trapping was conducted in three phases: first on rubbish dumps and water tanks (29 days), second on a Sooty Tern Colony (15 days) and finally, again on rubbish dumps and water tanks (9 days). The goal of reducing the negative effects of the Common myna on native wildlife by trapping as many individuals as possible has been reasonably covered. The population of mynas, estimated in some 1.000 to 1.200 birds, has been reduced by culling 623 birds in 53 days. This work has been done by one person using four traps. There is a low risk of re-infestation from birds flying by their own from St Helena, and the only transport between Ascension and St Helena has been conveniently informed regarding mynas using boats as pathway and how to avoid it. Considering the present damage of the mynas for wildlife, human health and security, it is high recommended that the local Ascension Island Government or related Institutions should decide to go for eradication as soon as possible. Live Arico - P.O.Box 1132 38008 – Santa Cruz de Tenerife Canary Islands, Spain. 2 Live Arico Environmental and Animal Protection – Invasive Species Department Register Charity number: 4709 C.I.F.: G/ 38602058 e-mail : [email protected] Phone: + 34 620 126 525 I n d e x INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... -

Behavior and Attendance Patterns of the Fork-Tailed Storm-Petrel

BEHAVIOR AND ATTENDANCE PATTERNS OF THE FORK-TAILED STORM-PETREL THEODORE R. SIMONS Wildlife Science Group, Collegeof Forest Resources, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 USA ABSTRACT.--Behavior and attendance patterns of breeding Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels (Ocea- nodromafurcata) were monitored over two nesting seasonson the Barren Islands, Alaska. The asynchrony of egg laying and hatching shown by these birds apparently reflects the influence of severalfactors, including snow conditionson the breedinggrounds, egg neglectduring incubation, and food availability. Communication between breeding birds was characterized by auditory and tactile signals.Two distinct vocalizationswere identified, one of which appearsto be a sex-specific call given by males during pair formation. Generally, both adults were present in the burrow on the night of egg laying, and the male took the first incubation shift. Incubation shiftsranged from 1 to 5 days, with 2- and 3-day shifts being the most common. Growth parameters of the chicks, reproductive success, and breeding chronology varied considerably between years; this pre- sumably relates to a difference in conditions affecting the availability of food. Adults apparently responded to changes in food availability during incubation by altering their attendance patterns. When conditionswere good, incubation shifts were shorter, egg neglectwas reduced, and chicks were brooded longer and were fed more frequently. Adults assistedthe chick in emerging from the shell. Chicks became active late in the nestling stage and began to venture from the burrow severaldays prior to fledging. Adults continuedto visit the chick during that time but may have reducedthe amountof fooddelivered. Chicks exhibiteda distinctprefledging weight loss.Received 18 September1979, accepted26 July 1980. -

Natural History and Breeding Behavior of the Tinamou, Nothoprocta Ornata

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VoL. 72 APRIL, 1955 No. 2 NATURAL HISTORY AND BREEDING BEHAVIOR OF THE TINAMOU, NOTHOPROCTA ORNATA ON the high mountainous plain of southern Peril west of Lake Titicaca live three speciesof the little known family Tinamidae. The three speciesrepresent three different genera and grade in size from the small, quail-sizedNothura darwini found in the farin land and grassy hills about Lake Titicaca between 12,500 and 13,300 feet to the large, pheasant-sized Tinamotis pentlandi in the bleak country between 14,000 and 16,000 feet. Nothoproctaornata, the third species in this area and the one to be discussedin the present report, is in- termediate in size and generally occurs at intermediate elevations. In Peril we have encountered Nothoproctabetween 13,000 and 14,300 feet. It often lives in the same grassy areas as Nothura; indeed, the two speciesmay be flushed simultaneouslyfrom the same spot. This is not true of Nothoproctaand the larger tinamou, Tinamotis, for although at places they occur within a few hundred yards of each other, Nothoproctais usually found in the bunch grassknown locally as ichu (mostly Stipa ichu) or in a mixture of ichu and tola shrubs, whereas Tinamotis usually occurs in the range of a different bunch grass, Festuca orthophylla. The three speciesof tinamous are dis- tinguished by the inhabitants, some of whom refer to Nothura as "codorniz" and to Nothoproctaas "perdiz." Tinamotis is always called "quivia," "quello," "keu," or some similar derivative of its distinctive call. The hilly, almost treeless countryside in which Nothoproctalives in southern Peril is used primarily for grazing sheep, alpacas,llamas, and cattle. -

An Introduction to Birds and Birding

AN INTRODUCTION TO BIRDS AND BIRDWATCHING Illustration: Rohan Chakravarty Bird Count India www.birdcount.in [email protected] PART- I ABOUT INDIAN BIRDS From small to large Photos: Garima Bhatia / Rajiv Lather From common to rare Photos: Nirav Bhatt / Navendu Lad From nondescript to magnificent Photos: Mohanram Kemparaju / Rajiv Lather And from deserts to dense forests Photos: Clement Francis / Ramki Sreenivasan India is home to over 1200 species of birds! Photos: Dr. Asad Rahmani, Nikhil Devasar, Dhritiman Mukherjee, Ramana Athreya, Judd Patterson Birds in Indian Culture and Mythology Source: wikipedia.org Photo: Alex Loinaz Garuda, the vahana of Lord Vishnu is thought to be a Brahminy Kite Birds in Indian Culture and Mythology Source: wikipedia.org Jatayu, sacrificed himself to rescue Sita from being kidnapped by Ravana. He was thought to be a vulture. Birds in Indian Culture and Mythology Photo: Nayan Khanolkar Photo: Kalyan Varma Sarus Cranes have a strong cultural significance in North India for their fidelity while hornbills find mention in the traditional folklore of the tribes of Arunachal Pradesh. Bird behaviour: Foraging Illustration: Aranya Pathak Broome Bird behaviour: Foraging Photos: Mike Ross, Josep del Hoyo, Pat Bonish, Shreeram M.V Bird behaviour: Migration Photos: Arthur Morris / Dubi Shapiro | Maps: Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and R. Suresh Kumar Bird behaviour: Songs Recordings: Pronoy Baidya / Neils Poul Dreyer Threats to birds Photos: www.conservationindia.org Cartoon: Rohan Chakravarty What is -

The Use of Starlicide in Preliminary Trials to Control Invasive Common

Conservation Evidence (2010) 7, 52-61 www.ConservationEvidence.com The use of Starlicide ® in preliminary trials to control invasive common myna Acridotheres tristis populations on St Helena and Ascension islands, Atlantic Ocean Chris J. Feare WildWings Bird Management, 2 North View Cottages, Grayswood Common, Haslemere, Surrey GU27 2DN, UK Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY Introduced common mynas Acridotheres tristis have been implicated as a threat to native biodiversity on the oceanic islands of St Helena and Ascension (UK). A rice-based bait treated with Starlicide® was broadcast for consumption by flocks of common mynas at the government rubbish tips on the two islands during investigations of potential myna management techniques. Bait was laid on St Helena during two 3-day periods in July and August 2009, and on Ascension over one 3-day period in November 2009. As a consequence of bait ingestion, dead mynas were found, especially under night roosts and also at the main drinking area on Ascension, following baiting. On St Helena early morning counts at the tip suggested that whilst the number of mynas fell after each treatment, lower numbers were not sustained; no reduction in numbers flying to the main roost used by birds using the tip as a feeding area was detected post-treatment. On Ascension, the number of mynas that fed at the tip and using a drinking site, and the numbers counted flying into night roosts from the direction of the tip, both indicated declines of about 70% (from about 360 to 109 individuals). Most dead birds were found following the first day of bait application, with few apparently dying after baiting on days 2 and 3. -

A Complete Species-Level Molecular Phylogeny For

Author's personal copy Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 47 (2008) 251–260 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A complete species-level molecular phylogeny for the ‘‘Eurasian” starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnus, Acridotheres, and allies): Recent diversification in a highly social and dispersive avian group Irby J. Lovette a,*, Brynn V. McCleery a, Amanda L. Talaba a, Dustin R. Rubenstein a,b,c a Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Laboratory of Ornithology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA b Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA c Department of Integrative Biology and Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Received 2 August 2007; revised 17 January 2008; accepted 22 January 2008 Available online 31 January 2008 Abstract We generated the first complete phylogeny of extant taxa in a well-defined clade of 26 starling species that is collectively distributed across Eurasia, and which has one species endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. Two species in this group—the European starling Sturnus vulgaris and the common Myna Acridotheres tristis—now occur on continents and islands around the world following human-mediated introductions, and the entire clade is generally notable for being highly social and dispersive, as most of its species breed colonially or move in large flocks as they track ephemeral insect or plant resources, and for associating with humans in urban or agricultural land- scapes. Our reconstructions were based on substantial mtDNA (4 kb) and nuclear intron (4 loci, 3 kb total) sequences from 16 species, augmented by mtDNA NDII gene sequences (1 kb) for the remaining 10 taxa for which DNAs were available only from museum skin samples. -

Winter Bird Feeding

BirdNotes 1 Winter Bird Feeding birds at feeders in winter If you feed birds, you’re in good company. Birding is one of North America’s favorite pastimes. A 2006 report from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that about 55.5 mil- lion Americans provide food for wild birds. Chickadees Titmice Cardinals Sparrows Wood- Orioles Pigeons Nuthatches Finches Grosbeaks Blackbirds Jays peckers Tanagers Doves Sunflower ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Safflower ◆ ◆ ◆ Corn ◆ ◆ ◆ Millet ◆ ◆ ◆ Milo ◆ ◆ Nyjer ◆ Suet ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Preferred ◆ Readily Eaten Wintertime—and the Living’s counting birds at their feeders during selecting the best foods daunting. To Not Easy this winterlong survey. Great Back- attract a diversity of birds, provide a yard Bird Count participants provide variety of food types. But that doesn’t n much of North America, winter valuable data with a much shorter mean you need to purchase one of ev- Iis a difficult time for birds. Days time commitment—as little as fifteen erything on the shelf. are often windy and cold; nights are minutes in mid-February! long and even colder. Lush vegeta- Which Seed Types tion has withered or been consumed, Types of Bird Food Should I Provide? and most insects have died or become uring spring and summer, most dormant. Finding food can be espe- lack-oil sunflower seeds attract songbirds eat insects and spi- cially challenging for birds after a D Bthe greatest number of species. ders, which are highly nutritious, heavy snowfall. These seeds have a high meat-to- abundant, and for the most part, eas- shell ratio, they are nutritious and Setting up a backyard feeder makes ily captured. -

Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone Bumbuna Hydroelectric

Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone Ministry of Energy and Power Public Disclosure Authorized Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project Environmental Impact Assessment Draft Final Report - Appendices Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized in association with BMT Cordah Ltd Appendices Document Orientation The present EIA report is split into three separate but closely related documents as follows: Volume1 – Executive Summary Volume 2 – Main Report Volume 3 – Appendices This document is Volume 3 – Appendices. Nippon Koei UK, BMT Cordah and Environmental Foundation for Africa i Appendices Glossary of Acronyms AD Anno Domini AfDB African Development Bank AIDS Auto-Immune Deficiency Syndrome ANC Antenatal Care BCC Behavioural Change Communication BHP Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project BWMA Bumbuna Watershed Management Authority BOD Biochemical Oxygen Demand BP Bank Procedure (World Bank) CBD Convention on Biodiversity CHC Community Health Centre CHO Community Health Officer CHP Community Health Post CLC Community Liaison Committee COD Chemical Oxygen Demand dbh diameter at breast height DFID Department for International Development (UK) DHMT District Health Management Team DOC Dissolved Organic Carbon DRP Dam Review Panel DUC Dams Under Construction EA Environmental Assessment ECA Export Credit Agency EFA Environmental Foundation for Africa EHS Environment, Health and Safety EHSO Environment, Health and Safety Officer EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA -

Records of Four Critically Endangered Songbirds in the Markets of Java Suggest Domestic Trade Is a Major Impediment to Their Conservation

20 BirdingASIA 27 (2017): 20–25 CONSERVATION ALERT Records of four Critically Endangered songbirds in the markets of Java suggest domestic trade is a major impediment to their conservation VINCENT NIJMAN, SUCI LISTINA SARI, PENTHAI SIRIWAT, MARIE SIGAUD & K. ANNEISOLA NEKARIS Introduction 1.2 million wild-caught birds (the vast majority Bird-keeping is a popular pastime in Indonesia, and of them songbirds) were sold in the Java and Bali nowhere more so than amongst the people of Java. markets each year. Taking a different approach, It has deep cultural roots, and traditionally a kukilo Jepson & Ladle (2005) made use of a survey of (bird in the Javanese language) was one of the five randomly selected households in the Javan cities things a Javanese man should pursue or obtain in of Jakarta, Bandung, Semarang and Surabaya, order to live a fulfilling life (the others being garwo, and Medan in Sumatra, which together make up a wife, curigo, a Javanese dagger, wismo, a house or a quarter of the urban Indonesian population, to a place to live, and turonggo, a horse, as a means estimate that between 600,000 and 760,000 wild- of transportation). A kukilo represents having a caught native songbirds were acquired each year. hobby, and it often takes the form of owning a Extrapolating this to the urban population of Java, perkutut (Zebra Dove Geopelia striata) or a kutilang which amounts to 60% of Indonesia’s total, it (Sooty-headed Bulbul Pycnonotus aurigaster) but suggests that a total of 1.4–1.8 million wild-caught also a wide range of other birds (Nash 1993, Chng native songbirds were acquired. -

Illegal Trade Pushing the Critically Endangered Black-Winged Myna Acridotheres Melanopterus Towards Imminent Extinction

Bird Conservation International, page 1 of 7 . © BirdLife International, 2015 doi:10.1017/S0959270915000106 Short Communication Illegal trade pushing the Critically Endangered Black-winged Myna Acridotheres melanopterus towards imminent extinction CHRIS R. SHEPHERD , VINCENT NIJMAN , KANITHA KRISHNASAMY , JAMES A. EATON and SERENE C. L. CHNG Summary The Critically Endangered Black-winged Myna Acridotheres melanopterus is being pushed towards the brink of extinction in Indonesia due to continued demand for it as a cage bird and the lack of enforcement of national laws set in place to protect it. The trade in this species is largely to supply domestic demand, although an unknown level of international demand also persists. We conducted five surveys of three of Indonesia’s largest open bird markets (Pramuka, Barito and Jatinegara), all of which are located in the capital Jakarta, between July 2010 and July 2014. No Black-winged Mynas were observed in Jatinegara, singles or pairs were observed during every survey in Barito, whereas up to 14 birds at a time were present at Pramuka. The average number of birds observed per survey is about a quarter of what it was in the 1990s when, on average, some 30 Black-winged Mynas were present at Pramuka and Barito markets. Current asking prices in Jakarta are high, with unbartered quotes averaging USD 220 per bird. Our surveys of the markets in Jakarta illustrate an ongoing and open trade. Dealers blatantly ignore national legislation and are fearless of enforcement actions. Commercial captive breeding is unlikely to remove pressure from remaining wild populations of Black-winged Mynas. Efforts to end the illegal trade in this species and to allow wild populations to recover are urgently needed.