The Mean Curvature of the Second Fundamental Form of a Hypersurface

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scalar Curvature and Geometrization Conjectures for 3-Manifolds

Comparison Geometry MSRI Publications Volume 30, 1997 Scalar Curvature and Geometrization Conjectures for 3-Manifolds MICHAEL T. ANDERSON Abstract. We first summarize very briefly the topology of 3-manifolds and the approach of Thurston towards their geometrization. After dis- cussing some general properties of curvature functionals on the space of metrics, we formulate and discuss three conjectures that imply Thurston’s Geometrization Conjecture for closed oriented 3-manifolds. The final two sections present evidence for the validity of these conjectures and outline an approach toward their proof. Introduction In the late seventies and early eighties Thurston proved a number of very re- markable results on the existence of geometric structures on 3-manifolds. These results provide strong support for the profound conjecture, formulated by Thur- ston, that every compact 3-manifold admits a canonical decomposition into do- mains, each of which has a canonical geometric structure. For simplicity, we state the conjecture only for closed, oriented 3-manifolds. Geometrization Conjecture [Thurston 1982]. Let M be a closed , oriented, 2 prime 3-manifold. Then there is a finite collection of disjoint, embedded tori Ti 2 in M, such that each component of the complement M r Ti admits a geometric structure, i.e., a complete, locally homogeneous RiemannianS metric. A more detailed description of the conjecture and the terminology will be given in Section 1. A complete Riemannian manifold N is locally homogeneous if the universal cover N˜ is a complete homogenous manifold, that is, if the isometry group Isom N˜ acts transitively on N˜. It follows that N is isometric to N=˜ Γ, where Γ is a discrete subgroup of Isom N˜, which acts freely and properly discontinuously on N˜. -

Toponogov.V.A.Differential.Geometry

Victor Andreevich Toponogov with the editorial assistance of Vladimir Y. Rovenski Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces A Concise Guide Birkhauser¨ Boston • Basel • Berlin Victor A. Toponogov (deceased) With the editorial assistance of: Department of Analysis and Geometry Vladimir Y. Rovenski Sobolev Institute of Mathematics Department of Mathematics Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy University of Haifa of Sciences Haifa, Israel Novosibirsk-90, 630090 Russia Cover design by Alex Gerasev. AMS Subject Classification: 53-01, 53Axx, 53A04, 53A05, 53A55, 53B20, 53B21, 53C20, 53C21 Library of Congress Control Number: 2005048111 ISBN-10 0-8176-4384-2 eISBN 0-8176-4402-4 ISBN-13 978-0-8176-4384-3 Printed on acid-free paper. c 2006 Birkhauser¨ Boston All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the writ- ten permission of the publisher (Birkhauser¨ Boston, c/o Springer Science+Business Media Inc., 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA) and the author, except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and re- trieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed in the United States of America. (TXQ/EB) 987654321 www.birkhauser.com Contents Preface ....................................................... vii About the Author ............................................. -

DISCRETE DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY: an APPLIED INTRODUCTION Keenan Crane • CMU 15-458/858 LECTURE 15: CURVATURE

DISCRETE DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY: AN APPLIED INTRODUCTION Keenan Crane • CMU 15-458/858 LECTURE 15: CURVATURE DISCRETE DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY: AN APPLIED INTRODUCTION Keenan Crane • CMU 15-458/858 Curvature—Overview • Intuitively, describes “how much a shape bends” – Extrinsic: how quickly does the tangent plane/normal change? – Intrinsic: how much do quantities differ from flat case? N T B Curvature—Overview • Driving force behind wide variety of physical phenomena – Objects want to reduce—or restore—their curvature – Even space and time are driven by curvature… Curvature—Overview • Gives a coordinate-invariant description of shape – fundamental theorems of plane curves, space curves, surfaces, … • Amazing fact: curvature gives you information about global topology! – “local-global theorems”: turning number, Gauss-Bonnet, … Curvature—Overview • Geometric algorithms: shape analysis, local descriptors, smoothing, … • Numerical simulation: elastic rods/shells, surface tension, … • Image processing algorithms: denoising, feature/contour detection, … Thürey et al 2010 Gaser et al Kass et al 1987 Grinspun et al 2003 Curvature of Curves Review: Curvature of a Plane Curve • Informally, curvature describes “how much a curve bends” • More formally, the curvature of an arc-length parameterized plane curve can be expressed as the rate of change in the tangent Equivalently: Here the angle brackets denote the usual dot product, i.e., . Review: Curvature and Torsion of a Space Curve •For a plane curve, curvature captured the notion of “bending” •For a space curve we also have torsion, which captures “twisting” Intuition: torsion is “out of plane bending” increasing torsion Review: Fundamental Theorem of Space Curves •The fundamental theorem of space curves tells that given the curvature κ and torsion τ of an arc-length parameterized space curve, we can recover the curve (up to rigid motion) •Formally: integrate the Frenet-Serret equations; intuitively: start drawing a curve, bend & twist at prescribed rate. -

NON-EXISTENCE of METRIC on Tn with POSITIVE SCALAR

NON-EXISTENCE OF METRIC ON T n WITH POSITIVE SCALAR CURVATURE CHAO LI Abstract. In this note we present Gromov-Lawson's result on the non-existence of metric on T n with positive scalar curvature. Historical results Scalar curvature is one of the simplest invariants of a Riemannian manifold. In general dimensions, this function (the average of all sectional curvatures at a point) is a weak measure of the local geometry, hence it's suspicious that it has no relation to the global topology of the manifold. In fact, a result of Kazdan-Warner in 1975 states that on a compact manifold of dimension ≥ 3, every smooth function which is negative somewhere, is the scalar curvature of some Riemannian metric. However people know that there are manifolds which carry no metric whose scalar scalar curvature is everywhere positive. The first examples of such manifolds were given in 1962 by Lichnerowicz. It is known that if X is a compact spin manifold and A^ 6= 0 then by Lichnerowicz formula (which will be discussed later) then X doesn't carry any metric with everywhere positive scalar curvature. Note that spin assumption is essential here, since the complex projective plane has positive sectional curvature and non-zero A^-genus. Despite these impressive results, one simple question remained open: Can the torus T n, n ≥ 3, carry a metric of positive scalar curvature? This question was settled for n ≤ 7 by R. Schoen and S. T. Yau. Their method involves the existence of smooth solution of Plateau problem, so the dimension restriction n ≤ 7 is essential. -

Curvatures of Smooth and Discrete Surfaces

Curvatures of Smooth and Discrete Surfaces John M. Sullivan The curvatures of a smooth curve or surface are local measures of its shape. Here we consider analogous quantities for discrete curves and surfaces, meaning polygonal curves and triangulated polyhedral surfaces. We find that the most useful analogs are those which preserve integral relations for curvature, like the Gauß/Bonnet theorem. For simplicity, we usually restrict our attention to curves and surfaces in euclidean three space E3, although many of the results would easily generalize to other ambient manifolds of arbitrary dimension. Most of the material here is not new; some is even quite old. Although some refer- ences are given, no attempt has been made to give a comprehensive bibliography or an accurate picture of the history of the ideas. 1. Smooth curves, Framings and Integral Curvature Relations A companion article [Sul06] investigated the class of FTC (finite total curvature) curves, which includes both smooth and polygonal curves, as a way of unifying the treatment of curvature. Here we briefly review the theory of smooth curves from the point of view we will later adopt for surfaces. The curvatures of a smooth curve γ (which we usually assume is parametrized by its arclength s) are the local properties of its shape invariant under Euclidean motions. The only first-order information is the tangent line; since all lines in space are equivalent, there are no first-order invariants. Second-order information is given by the osculating circle, and the invariant is its curvature κ = 1/r. For a plane curve given as a graph y = f(x) let us contrast the notions of curvature and second derivative. -

Differential Geometry: Curvature and Holonomy Austin Christian

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler Math Theses Math Spring 5-5-2015 Differential Geometry: Curvature and Holonomy Austin Christian Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/math_grad Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Christian, Austin, "Differential Geometry: Curvature and Holonomy" (2015). Math Theses. Paper 5. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/266 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Math at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in Math Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY: CURVATURE AND HOLONOMY by AUSTIN CHRISTIAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Mathematics David Milan, Ph.D., Committee Chair College of Arts and Sciences The University of Texas at Tyler May 2015 c Copyright by Austin Christian 2015 All rights reserved Acknowledgments There are a number of people that have contributed to this project, whether or not they were aware of their contribution. For taking me on as a student and learning differential geometry with me, I am deeply indebted to my advisor, David Milan. Without himself being a geometer, he has helped me to develop an invaluable intuition for the field, and the freedom he has afforded me to study things that I find interesting has given me ample room to grow. For introducing me to differential geometry in the first place, I owe a great deal of thanks to my undergraduate advisor, Robert Huff; our many fruitful conversations, mathematical and otherwise, con- tinue to affect my approach to mathematics. -

General Relativity Fall 2019 Lecture 11: the Riemann Tensor

General Relativity Fall 2019 Lecture 11: The Riemann tensor Yacine Ali-Ha¨ımoud October 8th 2019 The Riemann tensor quantifies the curvature of spacetime, as we will see in this lecture and the next. RIEMANN TENSOR: BASIC PROPERTIES α γ Definition { Given any vector field V , r[αrβ]V is a tensor field. Let us compute its components in some coordinate system: σ σ λ σ σ λ r[µrν]V = @[µ(rν]V ) − Γ[µν]rλV + Γλ[µrν]V σ σ λ σ λ λ ρ = @[µ(@ν]V + Γν]λV ) + Γλ[µ @ν]V + Γν]ρV 1 = @ Γσ + Γσ Γρ V λ ≡ Rσ V λ; (1) [µ ν]λ ρ[µ ν]λ 2 λµν where all partial derivatives of V µ cancel out after antisymmetrization. σ Since the left-hand side is a tensor field and V is a vector field, we conclude that R λµν is a tensor field as well { this is the tensor division theorem, which I encourage you to think about on your own. You can also check that explicitly from the transformation law of Christoffel symbols. This is the Riemann tensor, which measures the non-commutation of second derivatives of vector fields { remember that second derivatives of scalar fields do commute, by assumption. It is completely determined by the metric, and is linear in its second derivatives. Expression in LICS { In a LICS the Christoffel symbols vanish but not their derivatives. Let us compute the latter: 1 1 @ Γσ = @ gσδ (@ g + @ g − @ g ) = ησδ (@ @ g + @ @ g − @ @ g ) ; (2) µ νλ 2 µ ν λδ λ νδ δ νλ 2 µ ν λδ µ λ νδ µ δ νλ since the first derivatives of the metric components (thus of its inverse as well) vanish in a LICS. -

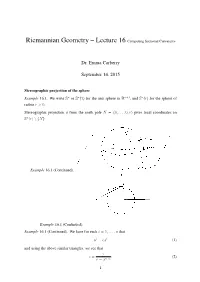

Riemannian Geometry – Lecture 16 Computing Sectional Curvatures

Riemannian Geometry – Lecture 16 Computing Sectional Curvatures Dr. Emma Carberry September 14, 2015 Stereographic projection of the sphere Example 16.1. We write Sn or Sn(1) for the unit sphere in Rn+1, and Sn(r) for the sphere of radius r > 0. Stereographic projection φ from the north pole N = (0;:::; 0; r) gives local coordinates on Sn(r) n fNg Example 16.1 (Continued). Example 16.1 (Continued). Example 16.1 (Continued). We have for each i = 1; : : : ; n that ui = cxi (1) and using the above similar triangles, we see that r c = : (2) r − xn+1 1 Hence stereographic projection φ : Sn n fNg ! Rn is given by rx1 rxn φ(x1; : : : ; xn; xn+1) = ;:::; r − xn+1 r − xn+1 The inverse φ−1 of stereographic projection is given by (exercise) 2r2ui xi = ; i = 1; : : : ; n juj2 + r2 2r3 xn+1 = r − : juj2 + r2 and so we see that stereographic projection is a diffeomorphism. Stereographic projection is conformal Definition 16.2. A local coordinate chart (U; φ) on Riemannian manifold (M; g) is conformal if for any p 2 U and X; Y 2 TpM, 2 gp(X; Y ) = F (p) hdφp(X); dφp(Y )i where F : U ! R is a nowhere vanishing smooth function and on the right-hand side we are using the usual Euclidean inner product. Exercise 16.3. Prove that this is equivalent to: 1. dφp preserving angles, where the angle between X and Y is defined (up to adding multi- ples of 2π) by g(X; Y ) cos θ = pg(X; X)pg(Y; Y ) and also to 2 2. -

SECTIONAL CURVATURE-TYPE CONDITIONS on METRIC SPACES 2 and Poincaré Conditions, and Even the Measure Contraction Property

SECTIONAL CURVATURE-TYPE CONDITIONS ON METRIC SPACES MARTIN KELL Abstract. In the first part Busemann concavity as non-negative curvature is introduced and a bi-Lipschitz splitting theorem is shown. Furthermore, if the Hausdorff measure of a Busemann concave space is non-trivial then the space is doubling and satisfies a Poincaré condition and the measure contraction property. Using a comparison geometry variant for general lower curvature bounds k ∈ R, a Bonnet-Myers theorem can be proven for spaces with lower curvature bound k > 0. In the second part the notion of uniform smoothness known from the theory of Banach spaces is applied to metric spaces. It is shown that Busemann functions are (quasi-)convex. This implies the existence of a weak soul. In the end properties are developed to further dissect the soul. In order to understand the influence of curvature on the geometry of a space it helps to develop a synthetic notion. Via comparison geometry sectional curvature bounds can be obtained by demanding that triangles are thinner or fatter than the corresponding comparison triangles. The two classes are called CAT (κ)- and resp. CBB(κ)-spaces. We refer to the book [BH99] and the forthcoming book [AKP] (see also [BGP92, Ots97]). Note that all those notions imply a Riemannian character of the metric space. In particular, the angle between two geodesics starting at a com- mon point is well-defined. Busemann investigated a weaker notion of non-positive curvature which also applies to normed spaces [Bus55, Section 36]. A similar idea was developed by Pedersen [Ped52] (see also [Bus55, (36.15)]). -

Riemannian Submanifolds: a Survey

RIEMANNIAN SUBMANIFOLDS: A SURVEY BANG-YEN CHEN Contents Chapter 1. Introduction .............................. ...................6 Chapter 2. Nash’s embedding theorem and some related results .........9 2.1. Cartan-Janet’s theorem .......................... ...............10 2.2. Nash’s embedding theorem ......................... .............11 2.3. Isometric immersions with the smallest possible codimension . 8 2.4. Isometric immersions with prescribed Gaussian or Gauss-Kronecker curvature .......................................... ..................12 2.5. Isometric immersions with prescribed mean curvature. ...........13 Chapter 3. Fundamental theorems, basic notions and results ...........14 3.1. Fundamental equations ........................... ..............14 3.2. Fundamental theorems ............................ ..............15 3.3. Basic notions ................................... ................16 3.4. A general inequality ............................. ...............17 3.5. Product immersions .............................. .............. 19 3.6. A relationship between k-Ricci tensor and shape operator . 20 3.7. Completeness of curvature surfaces . ..............22 Chapter 4. Rigidity and reduction theorems . ..............24 4.1. Rigidity ....................................... .................24 4.2. A reduction theorem .............................. ..............25 Chapter 5. Minimal submanifolds ....................... ...............26 arXiv:1307.1875v1 [math.DG] 7 Jul 2013 5.1. First and second variational formulas -

Chapter 13 Curvature in Riemannian Manifolds

Chapter 13 Curvature in Riemannian Manifolds 13.1 The Curvature Tensor If (M, , )isaRiemannianmanifoldand is a connection on M (that is, a connection on TM−), we− saw in Section 11.2 (Proposition 11.8)∇ that the curvature induced by is given by ∇ R(X, Y )= , ∇X ◦∇Y −∇Y ◦∇X −∇[X,Y ] for all X, Y X(M), with R(X, Y ) Γ( om(TM,TM)) = Hom (Γ(TM), Γ(TM)). ∈ ∈ H ∼ C∞(M) Since sections of the tangent bundle are vector fields (Γ(TM)=X(M)), R defines a map R: X(M) X(M) X(M) X(M), × × −→ and, as we observed just after stating Proposition 11.8, R(X, Y )Z is C∞(M)-linear in X, Y, Z and skew-symmetric in X and Y .ItfollowsthatR defines a (1, 3)-tensor, also denoted R, with R : T M T M T M T M. p p × p × p −→ p Experience shows that it is useful to consider the (0, 4)-tensor, also denoted R,givenby R (x, y, z, w)= R (x, y)z,w p p p as well as the expression R(x, y, y, x), which, for an orthonormal pair, of vectors (x, y), is known as the sectional curvature, K(x, y). This last expression brings up a dilemma regarding the choice for the sign of R. With our present choice, the sectional curvature, K(x, y), is given by K(x, y)=R(x, y, y, x)but many authors define K as K(x, y)=R(x, y, x, y). Since R(x, y)isskew-symmetricinx, y, the latter choice corresponds to using R(x, y)insteadofR(x, y), that is, to define R(X, Y ) by − R(X, Y )= + . -

Simulation of a Soap Film Catenoid

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kanazawa University Repository for Academic Resources Simulation of A Soap Film Catenoid ! ! Pornchanit! Subvilaia,b aGraduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Kanazawa University, Kakuma, Kanazawa 920-1192 Japan bDepartment of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Pathumwan, Bangkok 10330 Thailand E-mail: [email protected] ! ! ! Abstract. There are many interesting phenomena concerning soap film. One of them is the soap film catenoid. The catenoid is the equilibrium shape of the soap film that is stretched between two circular rings. When the two rings move farther apart, the radius of the neck of the soap film will decrease until it reaches zero and the soap film is split. In our simulation, we show the evolution of the soap film when the rings move apart before the !film splits. We use the BMO algorithm for the evolution of a surface accelerated by the mean curvature. !Keywords: soap film catenoid, minimal surface, hyperbolic mean curvature flow, BMO algorithm !1. Introduction The phenomena that concern soap bubble and soap films are very interesting. For example when soap bubbles are blown with any shape of bubble blowers, the soap bubbles will be round to be a minimal surface that is the minimized surface area. One of them that we are interested in is a soap film catenoid. The catenoid is the minimal surface and the equilibrium shape of the soap film stretched between two circular rings. In the observation of the behaviour of the soap bubble catenoid [3], if two rings move farther apart, the radius of the neck of the soap film will decrease until it reaches zero.