Pietro Mascagni: an Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Composers Mascagni and Leoncavallo Biography

Cavalleria Rusticana Composer Biography: Pietro Mascagni Mascagni was an Italian composer born in Livorno on December 7, 1863. His father was a baker and dreamed of a career as a lawyer for his son, but following the good reception obtained by Mascagni’s first compositions was persuaded to allow him to study music at the Milan Conservatoire, where his teachers included Amilcare Ponchielli and Michele Saladino, and where he shared a furnished room with his fellow-student Giacomo Puccini. His first compositions won him financial support to study at the Milan Conservatory. He was of a rebellious nature and intolerant of discipline, and in 1885 he left the Conservatoire to join a modest operetta company as conductor. He became part of the Compagnia Maresca and, together with his future wife, Lina Carbognani, settled in Cerignola (Apulia) in 1886, where he formed a symphony orchestra. Here Mascagni composed at a single stroke, in only two months, the one-act opera Cavalleria rusticana, based on the short story by Verga, which was to win him the first prize in the Second Sonzogno Competition for new operas. The innovative strength of the opera and the resounding worldwide success which followed its first performance (1890, Teatro Costanzi, Rome) marked the beginning of an artistic life rich in achievements and satisfactions, both as composer and as conductor. He became increasingly prominent as a conductor and in 1892 conducted his opera I Rantzau around Europe. Further successes included Amica (1905) and Isabeau (1911), alongside such failures as Le maschere (1901). In 1915 he experimented with writing for cinema in Rapsodia satanicawith Nino Oxilia. -

Otello Program

GIUSEPPE VERDI otello conductor Opera in four acts Gustavo Dudamel Libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on production Bartlett Sher the play by William Shakespeare set designer Thursday, January 10, 2019 Es Devlin 7:30–10:30 PM costume designer Catherine Zuber Last time this season lighting designer Donald Holder projection designer Luke Halls The production of Otello was made possible by revival stage director Gina Lapinski a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr. The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 345th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S otello conductor Gustavo Dudamel in order of vocal appearance montano a her ald Jeff Mattsey Kidon Choi** cassio lodovico Alexey Dolgov James Morris iago Željko Lučić roderigo Chad Shelton otello Stuart Skelton desdemona Sonya Yoncheva This performance is being broadcast live on Metropolitan emilia Opera Radio on Jennifer Johnson Cano* SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Thursday, January 10, 2019, 7:30–10:30PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA Stuart Skelton in Chorus Master Donald Palumbo the title role and Fight Director B. H. Barry Sonya Yoncheva Musical Preparation Dennis Giauque, Howard Watkins*, as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello J. David Jackson, and Carol Isaac Assistant Stage Directors Shawna Lucey and Paula Williams Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Prompter Carol Isaac Italian Coach Hemdi Kfir Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Assistant Scenic Designer, Properties Scott Laule Assistant Costume Designers Ryan Park and Wilberth Gonzalez Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department; Angels the Costumiers, London; Das Gewand GmbH, Düsseldorf; and Seams Unlimited, Racine, Wisconsin Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses strobe effects. -

Mascagni E Il Teatro Goldoni: Un Binomio Indissolubile

Mascagni e il Teatro Goldoni: un binomio indissolubile di Alberto Paloscia, Direttore artistico stagione lirica Fondazione Teatro della Città di Livorno “Carlo Goldoni” INTERVENTI Un’altra immagine positore, dopo gli anni di oscura gavetta del giovane Pietro Mascagni prima come direttore di una compagnia girovaga di operette e successivamente come animatore della vita musicale della provincia pugliese nelle veste di fonda- tore e responsabile della Filarmonica di Cerignola, abbatteva le quinte e i fondali del melodramma un po’ imbalsamato del XIX secolo e fondava, con il crudo ed ele- mentare realismo mediterraneo ereditato da Verga, un nuovo stile operistico: quello del verismo e della “Giovine Scuola Italia- na” a cui si sarebbero affiliati, di lì a poco, i nuovi ‘campioni’ del teatro musicale italia- Mascagni e il Teatro Goldoni Teatro il e Mascagni no: Leoncavallo, Puccini, Giordano, Cilèa. Dal 1890 al 1984: quasi un secolo di spettacoli storici Pietro Mascagni e la sua musica possono nel nome di Mascagni essere considerati a buon diritto i più au- Il 14 agosto 1890, infiammato dalla calura tentici protagonisti della gloriosa storia della riviera labronica, Cavalleria approda operistica del Teatro Goldoni di Livorno. nel maggiore teatro della città di Livorno, Il primo importante capitolo è la première appena tre mesi dopo il trionfo arriso nel- per Livorno dell’opera ‘prima’ del giovane la prestigiosa sede del Teatro Costanzi di astro nascente livornese, destinata a dare Roma all’atto unico vincitore del Concor- una svolta decisiva -

Cavalleria Rusticana I Pagliacci Usporedno Sa Sve Brojnijim Izvedbama Prvi Su Put Zajedno Izvedeni 22

P. Mascagni CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA R. Leoncavallo: I PAGLIAccI Nedjelja, 3. svibnja 2015., 18:30 sati. Foto: Metropolitan opera P. Mascagni CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA R. Leoncavallo: I PAGLIAccI Nedjelja, 3. svibnja 2015., 18:30 sati. THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Pietro Mascagni CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA Opera u jednom činu Libreto: Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti i Guido Menasci prema istoimenoj noveli Giovannija Verge NEDJELJA, 3. SVIBNJA 2015. POčETAK U 18 SATI I 30 MINUTA. Praizvedba: Teatro Costanzi, Rim, 17. svibnja 1890. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Druga operna stagiona, Zagreb, 29. svibnja 1893. Prva izvedba ansambla Metropolitana 4. prosinca 1891. u Chicagu Premijera ove izvedbe u Metropolitanu: 14. travnja 2015. ZBOR I ORKESTAR METROPOLITANA SANTUZZA Eva-Maria Westbroek ZBORovođa Donald Palumbo TURIDDU Marcelo Álvarez DIRIGENT Fabio Luisi ALFIO George Gagnidze REDATELJ David McVicar LUCIA Jane Bunnell SCENOGRAF Rae Smith LOLA Ginger Costa-Jackson Tekst: talijanski Stanka poslije Cavallerije rusticane. Titlovi: engleski Svršetak oko 22 sata. Ruggero Leoncavallo I PAGLIACCI Foto:Metropolitan opera Opera u dva čina s prologom Libreto: skladatelj NEDJELJA, 3. SVIBNJA 2015. POčETAK U 18 SATI I 30 MINUTA. Praizvedba: Teatro Dal Verme, Milano, 21. kolovoza 1892. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Treća operna stagiona, Zagreb, 22. travnja 1894. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu: 11. prosinca 1893. Premijera ove izvedbe u Metropolitanu: 25. travnja 2015. KOSTIMOGRAF Moritz Junge CANIO/PAGLIACCIO Marcelo Álvarez OBLIKOVATELJICA RASVJETE Paule Constable NEDDA/COLOMBINA Patricia Racette KOREOGRAF Andrew George TONIO/TADDEO George Gagnidze KONZULTANT ZA VODVILJ Emil Wolk BEPPE/ARLECCHINO Andrew Stenson SILVIO Lucas Meachem Tekst: talijanski Titlovi: engleski CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA Radnja se događa na Uskrs u sicilijanskom selu. -

Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected]

Nineteenth-Century Music Review, 14 (2017), pp 211–242. © Cambridge University Press, 2016 doi:10.1017/S1479409816000082 First published online 8 September 2016 Romantic Nostalgia and Wagnerismo During the Age of Verismo: The Case of Alberto Franchetti* Davide Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected] The world premiere of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana on 17 May 1890 immediately became a central event in Italy’s recent operatic history. As contemporary music critic and composer, Francesco D’Arcais, wrote: Maybe for the first time, at least in quite a while, learned people, the audience and the press shared the same opinion on an opera. [Composers] called upon to choose the works to be staged, among those presented for the Sonzogno [opera] competition, immediately picked Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana as one of the best; the audience awarded this composer triumphal honours, and the press 1 unanimously praised it to the heavens. D’Arcais acknowledged Mascagni’smeritsbut,inthesamearticle,alsourgedcaution in too enthusiastically festooning the work with critical laurels: the dangers of excessive adulation had already become alarmingly apparent in numerous ill-starred precedents. In the two decades prior to its premiere, several other Italian composers similarly attained outstanding critical and popular success with a single work, but were later unable to emulate their earlier achievements. Among these composers were Filippo Marchetti (Ruy Blas, 1869), Stefano Gobatti (IGoti, 1873), Arrigo Boito (with the revised version of Mefistofele, 1875), Amilcare Ponchielli (La Gioconda, 1876) and Giovanni Bottesini (Ero e Leandro, 1879). Once again, and more than a decade after Bottesini’s one-hit wonder, D’Arcais found himself wondering whether in Mascagni ‘We [Italians] have finally [found] … the legitimate successor to [our] great composers, the person 2 who will perpetuate our musical glory?’ This hoary nationalist interrogative returned in 1890 like an old-fashioned curse. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W. -

Pietro Mascagni Ruggero Leoncavallo

PIETRO MASCAGNI CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA RUGGERO LEONCAVALLO PAGLIACCI JONAS KAUFMANN LIUDMYLA MONASTYRSKA ANNALISA STROPPA AMBROGIO MAESTRI MARIA AGRESTA SÄCHSISCHE STAATSKAPELLE DRESDEN CONDUCTED BY CHRISTIAN THIELEMANN STAGED BY PHILIPP STÖLZL SALZBURG EASTER FESTIVAL PIETRO MASCAGNI CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA Santuzza Liudmyla Monastyrska Turiddu Jonas Kaufmann Lucia Stefania Toczyska Alfio Ambrogio Maestri Lola Annalisa Stroppa Length: approx. 75' Cat. no. A 040 50042 RUGGERO LEONCAVALLO PAGLIACCI Nedda Maria Agresta Canio Jonas Kaufmann Tonio Dimitri Platanias Beppe Tansel Akzeybek Silvio Alsessio Arduini Length: approx. 90' “Opera as Great Romantic Cinema”, wrote the Salzburger Nachrichten Cat. no. A 040 50043 about the two one-act operas Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci, which proved real crowd-pullers and ensured record attendances at the Easter Orchestra Staatskapelle Dresden Festival. No wonder, for “Jonas Kaufmann, for whom it was in both cases Conductor Christian Thielemann his role debut, was on stellar form twice” (Daily Telegraph). “Kaufmann sings Chorus Staatsopernchor Dresden both parts so lyrically, with such italianità, mellow with impeccable highs, Salzburger Bachchor as to be a pure delight.” (Kurier) Equally impressive are Thielemann – “the Salzburger Festspiele & uber-conductor” (Telegraph) – and the Dresdeners, who “take time for Theater Kinderchor sensitive, melodious soul portraits, while delivering consummate drama Chorus Master Jörn H. Andresen at just the right moment. What we hear from the pit is sensational in its Stage Director Philipp Stölzl nuances.” (Kurier) Video Director Brian Large The scene is set by film and opera director Philipp Stölzl, contributing to the performance’s huge fascination: Stölzl divides the stage into several levels, Shot in HDTV 1080/50i staging crowd scenes below, private feelings above – the latter projected A co-production of ORF, 3sat, with filmic close-ups – doubling and trebling the action. -

Tosca Nixon in China a Midsummer Night's Dream

TOSCA NIXON IN CHINA A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S 19 DREAM THE GONDOLIERS BREAKING THE WAVES ZANETTO SUSANNA’S SECRET IRIS 20CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA ZINGARI UTOPIA, LIMITED FOX-TOT! MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG 5 Subscription Information 6 Tosca 8 Nixon in China 10 A Midsummer Night’s Dream 12 The Gondoliers 14 Breaking the Waves 16 Opera in Concert 20 Opera Highlights 22 Fox-tot! 24 Merrily We Roll Along 26 Amadeus & The Bard 28 Pop-up Opera 32 Emerging Artists 33 Opera Unwrapped 34 Dementia Friendly Performances 36 Audio-described Performances 37 Pre-show Talks 38 Get Involved 40 Box Office Information A huge thank you to all our business sponsors and corporate members: Thanks also to our corporate supporters: Accenture, Caledonian MacBrayne, Cameron, Eusebi Deli, Glasgow Chamber of Commerce, Glasgow Memory Clinic, M.A.C., NorthLink Ferries and Pentland Ferries. WELCOME TO SCOTTISH OPERA’S 2019|20 SEASON Scottish Opera has been entertaining At a time when, perhaps more than ever, audiences the length and breadth of the we are all thinking and talking about country for over 56 years, and still at the heart partnership, we are proud of the relationships of all we do are the words of our founder, that are critical both to Scottish Opera’s success Sir Alexander Gibson, whose vision was and to our ability to create new work for you. ‘to lay the treasures of opera at the feet We don’t work in isolation, and this Season of the people of Scotland’. exemplifies this spirit of collaboration across the world of opera, embracing our partnerships In our 2019/20 Season, we are delighted and co-productions with festivals, companies to take forward his momentous legacy and opera houses in Scotland, England, with a wealth of operatic fare – including Australia, Denmark, Spain and the United 12 operas – that takes us to over 50 venues, States, and with artists and creative teams and is augmented by numerous events in from near and far. -

Understanding the Lirico-Spinto Soprano Voice Through the Repertoire of Giovane Scuola Composers

UNDERSTANDING THE LIRICO-SPINTO SOPRANO VOICE THROUGH THE REPERTOIRE OF GIOVANE SCUOLA COMPOSERS Youna Jang Hartgraves Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Jeffrey Snider, Major Professor William Joyner, Committee Member Silvio De Santis, Committee Member Stephen Austin, Chair of the Division of Vocal Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Hartgraves, Youna Jang. Understanding the Lirico-Spinto Soprano Voice through the Repertoire of Giovane Scuola Composers. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 53 pp., 10 tables, 6 figures, bibliography, 66 titles. As lirico-spinto soprano commonly indicates a soprano with a heavier voice than lyric soprano and a lighter voice than dramatic soprano, there are many problems in the assessment of the voice type. Lirico-spinto soprano is characterized differently by various scholars and sources offer contrasting and insufficient definitions. It is commonly understood as a pushed voice, as many interpret spingere as ‘to push.’ This dissertation shows that the meaning of spingere does not mean pushed in this context, but extended, thus making the voice type a hybrid of lyric soprano voice type that has qualities of extended temperament, timbre, color, and volume. This dissertation indicates that the lack of published anthologies on lirico-spinto soprano arias is a significant reason for the insufficient understanding of the lirico-spinto soprano voice. The post-Verdi Italian group of composers, giovane scuola, composed operas that required lirico-spinto soprano voices. -

The Opera: a Brief Overview

The opera: a brief overview Claudio Toscani Cavalleria rusticana by Pietro Mascagni Pagliacci by Ruggero Leoncavallo When Pietro Mascagni won the Sonzogno prize for an opera in a single act, he was a complete unknown. Even so, the excitement roused and the extraordinary success met by Cavalleria rusticana on its first night at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome on 17th May 1890 are almost unknown in the history of opera. What the audience saw on stage appeared to be the fruit of a new sensitivity: the attention for the lower social classes that verist literatu - re had been preaching for some time as an inevitable necessity in politics and the arts. But that was not all: by placing ordinary characters at the centre of the opera and focusing the plot on a brutal case of the time, his Cavalleria rusticana broke the familiar mould of romantic opera, which other literary movements had failed to do. Another factor was, of course, the sharpness of the violent and dramatic action, along with an overwhelming, although not always refined musical vein. Success was immediate and worldwide. In Giovanni Verga’s short story of the same title, from which the libretto was taken, the characters move in and are deeply part of a Sicilian society imbued with age-old codes of behaviour. Their margin for initiative is practically non- existent and reflects the conviction held by Italian verists and French naturalists, that the environment has a determining influence on the individual’s psycho - logy. Therefore, the dramatic roles in Mascagni’s opera are rigid and correspond to stereotypes. -

IRIS Libretto-Edited

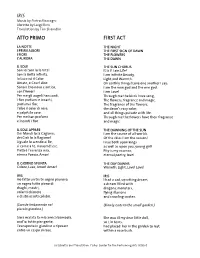

IRIS Music by Pietro Mascagni Libretto by Luigi Illica Translation by Tim Shaindlin ATTO PRIMO FIRST ACT LA NOTTE THE NIGHT I PRIMI ALBORI THE FIRST SIGN OF DAWN I FIORI THE FLOWERS L'AURORA THE DAWN IL SOLE THE SUN CHORUS Son Io! Son Io la Vita! It is I! I am Life! Son la Beltà infinita, I am infinite Beauty, la Luce ed il Calor. Light and Warmth. Amate, o Cose! dico: Oh earthly things! Love one another I say: Sono il Dio novo e antico, I am the new god and the one god. son l'Amor! I am Love! Per me gli augeli han canti, Through me the birds have song, I fior profumi e incanti, The flowers, fragrance and magic. profumi i fior, The fragrance of the flowers, l'albe il color di rose, the dawn's rosy color, e palpiti le cose. and all things pulsate with life. Per me han profumi Through me the flowers have their fragrance e incanti i fior. and magic. IL SOLE APPARE THE DAWNING OF THE SUN Dei Mondi Io la Cagione; I am the source of all worlds. dei Cieli Io la Ragione! Of the skies I am the reason! Uguale Io scendo ai Re, I rise both upon kings sì come a te, mousmè! ecc. as well as upon you, young girl! Pietà è l'essenza mia, Pity is my essence, eterna Poesia, Amor! eternal poetry, love! IL GIORNO SPUNTA THE DAY DAWNS Calore, Luce, Amor! Amor! Warmth, Light, Love! Love! IRIS IRIS Ho fatto un triste sogno pauroso, I had a sad, upsetting dream, un sogno tutto pieno di a dream filled with draghi, mostri, dragons, monsters, volanti chimere flying illusions e di striscianti cólubri. -

Performing Fascism: Opera, Politics, and Masculinities in Fascist Italy, 1935-1941

Performing Fascism: Opera, Politics, and Masculinities in Fascist Italy, 1935-1941 by Elizabeth Crisenbery Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Advisor ___________________________ Benjamin Earle ___________________________ Philip Rupprecht ___________________________ Louise Meintjes ___________________________ Roseen Giles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2020 ABSTRACT Performing Fascism: Opera, Politics, and Masculinities in Fascist Italy, 1935-1941 by Elizabeth Crisenbery Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Advisor ___________________________ Benjamin Earle ___________________________ Philip Rupprecht ___________________________ Louise Meintjes ___________________________ Roseen Giles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2020 Copyright by Elizabeth Crisenbery 2020 Abstract Roger Griffin notes that “there can be no term in the political lexicon which has generated more conflicting theories about its basic definition than ‘fascism’.” The difficulty articulating a singular definition of fascism is indicative of its complexities and ideological changes over time. This dissertation offers