Introducing Robert Smalls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

FORMER MEMBERS H 1870–1887 ������������������������������������������������������������������������ Robert Smalls 1839 –1915 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE H 1875–1879; 1882–1883; 1884–1887 REPUBLICAN FROM SOUTH CAROLINA n escaped slave and a Civil War hero, Robert Smalls publication of his name and former enslaved status in A served five terms in the U.S. House, representing northern propaganda proved demoralizing for the South.7 a South Carolina district described as a “black paradise” Smalls spent the remainder of the war balancing his role because of its abundant political opportunities for as a spokesperson for African Americans with his service freedmen.1 Overcoming the state Democratic Party’s in the Union Armed Forces. Piloting both the Planter, repeated attempts to remove that “blemish” from its goal which was re-outfitted as a troop transport, and later the of white supremacy, Smalls endured violent elections and a ironclad Keokuk, Smalls used his intimate knowledge of the short jail term to achieve internal improvements for coastal South Carolina Sea Islands to advance the Union military South Carolina and to fight for his black constituents in the campaign in nearly 17 engagements.8 face of growing disfranchisement. “My race needs no special Smalls’s public career began during the war. He joined defense, for the past history of them in this country proves free black delegates to the 1864 Republican National them to be equal of any people anywhere,” Smalls asserted. Convention, the first of seven total conventions he “All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”2 attended as a delegate.9 While awaiting repairs to the Robert Smalls was born a slave on April 5, 1839, in Planter, Smalls was removed from an all-white streetcar Beaufort, South Carolina. -

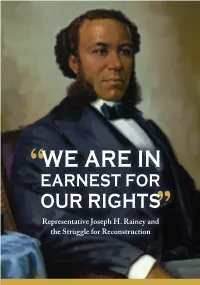

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

16Goodreads the History Book Club

29/04/2015 Goodreads | The History Book Club AMERICAN GOVERNMENT: HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES (showing 143 of 43) Title / Author / ISBN Home My Books Groups Recommendations Explore The History Book Club discussion AMERICAN GOVERNMENT > HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 208 views The History Book Club Comments (showing 143 of 43) (43 new) post a comment » date newest » message 1: by Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief (new) May 26, 2011 08:12PM Group Home Events Invite People This is a thread which can be used to discuss the House of Representatives. Bookshelf Photos Members Discussions Videos Polls flag * message 2: by Alisa (last edited Aug 05, 2013 01:50PM) (new) May 26, 2011 09:03PM search discussion posts search I recently purchased this book and am looking forward to reading it. unread topics | mark unread Capitol Men: The Epic Story of Reconstruction Through the Lives of the First Black Congressmen Primeiro apê Conquiste seu sonho by Philip Dray com a MRV. Mensais a Synopsis: partir de 299. Simule. Reconstruction was a time of idealism and sweeping change, as the victorious Union created citizenship rights for the freed slaves and granted the vote to black men. Sixteen black Southerners, elected to the U.S. Congress, arrived in Washington to advocate reforms such as public education, equal rights, land distribution, and the suppression of the Ku Klux Klan. But these men faced astounding odds. They were belittled as corrupt and inadequate by their white political opponents, who used legislative trickery, libel, bribery, and the brutal intimidation of their constituents to rob them of their base of support. -

Reconstruction Era U.S

National Park Service Reconstruction Era U.S. Department of the Interior Reconstruction Era National Monument Five Generations on Smith’s Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina The Reconstruction era, 1861-1898, was the historic period in which the United LOC Image / LC-DIG-ppmsc-00057 States grappled with the question of how to integrate millions of newly freed African Americans into social, political, economic and labor systems. The historical events that transpired in Beaufort County, South Carolina, make it an ideal place to tell stories of experimentation, transformation, hope, accomplishment, and disappointment. The Rise of Reconstruction In November 1861 the Sea Islands or people could begin integrating themselves into in South Carolina “Lowcountry” of southeastern South Carolina free society. Many enlisted into the army, and the came under Union control. Wealthy plantation government began early efforts to redistribute owners fled as Federal forces came ashore. More land to former slaves. Missionaries and other than 10,000 African Americans — about one- groups established schools, and some of the third of the enslaved population — refused to Reconstruction era’s most significant African flee the area with their former owners. American politicians, including Robert Smalls, came to prominence here. Beaufort County became one of the first places in the United States where formerly enslaved The Port Royal Experiment With Federal forces in charge of the Sea Islands, Towne and Ellen Murray from Pennsylvania the military occupation was remodeled into a were among the first northern teachers to arrive novel social venture. The effort to help formerly in Beaufort County. They soon moved their enslaved people become self-sufficient became school into the Brick Church, a Baptist church known as the Port Royal Experiment. -

GULLAH GEECHEE SUMMER SCHOOL South Carolina, Georgia and Florida — PART I: Origins and Early Development | June 6, 2018 from Pender County, North Carolina, to St

7/8/2018 + The Corridor is a federal National Heritage Area and it was established by Congress to recognize the unique culture of the Gullah Geechee people who have traditionally resided in the coastal areas and the sea islands of North Carolina, GULLAH GEECHEE SUMMER SCHOOL South Carolina, Georgia and Florida — PART I: Origins and Early Development | June 6, 2018 from Pender County, North Carolina, to St. Johns County, Florida. © 2018 Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission Do not reproduce without permission. + + Overview Overview “Gullah” or “Geechee”: Etymologies and Conventions West African Origins of Gullah Geechee Ancestors First Contact: Native Americans, Africans and Europeans Transatlantic Slave Trade through Charleston and Savannah Organization of Spanish Florida + England’s North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia Colonies The Atlantic Rice Coast Charter Generation of Africans in the Low Country Incubation of Gullah Geechee Creole Culture in the Sea Colonies Islands and Coastal Plantations ©Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission | Do not reproduce without permission. ©Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission | Do not reproduce without permission. + + “Gullah” or “Geechee”? “Gullah” or “Geechee”? Scholars are not in agreement as to the origins of the terms “Although Gullah and Geechee — terms whose “Gullah” and “Geechee.” origins have been much debated and may trace to specific African tribes or words — are often Gullah people are historically those located in coastal South used interchangeably these days, Mrs. [Cornelia Carolina and Geechee people are those who live along the Walker] Bailey always stressed that she was Georgia coast and into Florida. Geechee. And, specifically, Saltwater Geechee (as opposed to the Freshwater Geechee, who Geechee people in Georgia refer to themselves as “Freshwater lived 30 miles inland). -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

Grade 5 Packet 5.Pdf

Introducing the Words Read the following nonfiction narrative about a tourist attraction with an odd history. Notice how the highlighted words are used. These are the words you will be learning in this unit. (Nonfiction Narrative) he well diggers on William Newell's farm News of this singular discovery traveled fast. T in Cardiff, New York, got quite a shock Was this proof that giants had once walked one October morning in 1869. A few feet the earth? People from all over swarmed to down, their shovels uncovered a ten-foot long see the giant fossil. Newell's relative, George man. The body appeared to be petrified-that Hull, spotted a money-making opportunity and is, over a very long time, it had turned to stone. charged each visitor ten cents a peek. As the crowds increased, Hull raised the price to fifty page »4 =, • xi cents, the equivalent of about six dollars today. Soon, a group of businessmen began to •3, {' pursue Hull, begging him to sell them "the "w' jg" Kr; Cardiff Giant." Hull finally agreed to a price \'[A « The Cardiff Giant { Crowds formed to see the Giant. 140 f $37,000, and the stone creature was moved Why would George Hull do such a thing? Syracuse, New York. Now even more people At the time of the hoax, many people believed ined up to see it. that real-life giants had once walked the earth. Among the visitors were several Hull disagreed. Apparently, he just wanted aleontologists-scientists who study ancient to poke fun at this belief. -

Review 25 Robert Smalls

Called "The Gullah Statesman," Robert Smalls served longer in Congress than any other black Carolinian except Joseph Hayne Rainey. After reading Smalls' biography that is provided, complete the activities on the next page. (See page 245 in your textbook for a picture of Robert Smalls.) ROBERT SMALLS The future Civil War hero and Congressman was born into slavery on April 5, 1839, the only child of Lydia, a house-servant of Henry McKee of Beaufort. Young Robert became the favorite of his new master, John McKee who inherited him in 1848. Afraid that her son would not understand the horrors of slavery, Lydia forced her son to watch slaves being whipped in the Beaufort jail and to attend slave auctions at the Arsenal. In 1851 at the age of seventeen Smalls was hired out to work in Charleston. Eventually he was allowed to purchase his families freedom and that of his wife, whom he married in 1856. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Smalls was pressed into service by the Confederate authorities to pilot The Planter , a transport steamer assigned to Charleston harbor and the coastal waterways. In the cold hours before dawn on May 13, 1862, Smalls and the black members of the crew seized the ship and sailed it into the Union lines. On December 1, 1863, when the commander of The Planter deserted under attack, Smalls took charge and maneuvered the ship to safety. Subsequently he was promoted to the rank of captain and given command of the steamer. During Reconstruction Smalls became political leader of his native district and earned the title, "King of Beaufort." A Republican, he nevertheless won the respect of whites by his moderate political views and his charity toward the family of his former owner. -

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

H PART ONE H Former Black-American Members “The Fifteenth Amendment in Flesh and Blood” THE SYMBOLIC GeneratION OF BLACK AMERICans IN Congress, 1870–1887 When Senator Hiram Revels of Mississippi—the first African American to serve in Congress—toured the United States in 1871, he was introduced as the “Fifteenth Amendment in flesh and blood.”1 Indeed, the Mississippi-born preacher personified African-American emancipation and enfranchisement. On January 20, 1870, the state legislature chose Revels to briefly occupy a U.S. Senate seat, previously vacated by Albert Brown when Mississippi seceded from the Union in 1861.2 As Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts escorted Revels to the front of the chamber to take his oath on February 25, the Atlanta Constitution reported that “the crowded galleries rose almost en masse, and each particular neck was stretched to its uttermost to get a view. A curious crowd (colored and white) rushed into the Senate chamber and gazed at the colored senator, some of them congratulating him. A very respectable looking, well dressed company of colored men and women then came up and took Revels captive, and bore him off in glee and triumph.”3 The next day, the Chicago Tribune jubilantly declared that “the first letter with the frank of a negro was dropped in the Capitol Post Office.”4 But Revels’s triumph was short-lived. When his appoint- Joseph Rainey of South Carolina, the first black Representative in Congress, earned the distinction of also being the first black man to preside over a session of the House, in April 1874. -

Three Sides of the Smalls Story Parent Guide,Page 1 of 2

OurStory: Full Steam to Freedom Three Sides of the Smalls Story Parent Guide, page 1 of 2 Read the “Directions” sheets for step-by-step instructions. SUMMARY In this activity, students will identify and analyze the historical data found within two newspapers reporting on Robert Smalls and the CSS Planter. WHY Through analyzing these two primary sources, students can better exercise critical thinking skills and consider perspective in written documents. Most documents include a bias of some kind, and comparing two stories about the same event helps students understand the roles of bias and perspective. TIME ■ 30 minutes or more, depending on student reading levels RECOMMENDED AGE GROUP This activity will work best for children in 4th through 6th grade. CHALLENGE WORDS See the individual articles for definitions. GET READY ■ Read Seven Miles to Freedom together. Seven Miles to Freedom is a biography of Robert Smalls, a brave man who used his boat-piloting skills to escape slavery and help the Union navy during the Civil War. For tips on reading this book together, check out the Guided Reading Activity (http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/pdf/ smalls/smalls_reading.pdf). ■ Read the Step Back in Time sheets. Students will need a basic understanding of the Civil War to complete this activity thoughtfully. More information at http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/activities/smalls/ OurStory: Full Steam to Freedom Three Sides of the Smalls Story Parent Guide, page 2 of 2 YOU NEED ■ Directions sheets (attached) ■ Step Back in Time sheets (attached) ■ Copies of the ThinkAbout sheet (attached) ■ Copies of the transcripts of articles from the New York Herald and the Charleston Daily Courier (attached) ■ 1 or more copies of Seven Miles to Freedom More information at http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/activities/smalls/ OurStory: Full Steam to Freedom Three Sides of the Smalls Story Step Back in Time, page 1 of 2 For more information, visit the National Museum of American History website http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/activities/smalls. -

Robert Smalls—February 17, 2021 the Story of Robert Smalls Is One of My Favorites in American History

Robert Smalls—February 17, 2021 The story of Robert Smalls is one of my favorites in American History. Robert Smalls was born in Beaufort, South Carolina, on April 5, 1839 and worked as a house slave until the age of 12. At that point his owner, John K. McKee, sent him to Charleston to work as a waiter, ship rigger, and sailor, with all earnings going to McKee. In his teen years, his love of the sea led him to work on the docks and wharves of Charleston. As a result of this work, eventually Smalls became very knowledgeable about Charleston harbor. This arrangement continued until Smalls was 18 when he negotiated to keep all but $15 of his monthly pay, a deal which allowed Smalls to begin saving money. The savings that he accumulated were used to eventually purchase his wife and children from their owner for a sum of $800. In 1861 Smalls was hired as a deckhand on the Confederate transport steamer The Planter captained by General Roswell Ripley, the commander of the Second Military District of South Carolina. The Planter was assigned the job of delivering armaments to the Confederate forts. However, the Union Navy has set up a blockade around much of the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. To the Confederate the Northern blockade was another example of northern enslavement of the south. The Confederates were dug in defending Charleston, S.C., and its coastal waters, dense with island forts, including Sumter, where the first shots of the Civil War were fired exactly one year and one month before. -

Robert Smalls Resources

Essential Civil War Curriculum | Ethan J. Kytle, Robert Smalls | September 2020 Robert Smalls By Ethan J. Kytle, California State University, Fresno Resources If you can read only one book Author Title. City: Publisher, Year. Lineberry, Cate Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls’ Escape from Slavery to Union Hero. New York: Picador, 2017. Books and Articles Author Title. City: Publisher, Year. Billingsley, Andrew Yearning to Breathe Free: Robert Smalls of South Carolina and His Families. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007. Dray, Philip Capitol Men: The Epic Story of Reconstruction Through the Lives of the First Black Congressmen. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2008. Holt, Thomas C. Black over White: Negro Political Leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977. Miller Jr., Edward A. Gullah Statesman: Robert Smalls from Slavery to Congress, 1839-1915. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1995. Uya, Okon Edet From Slavery to Political Service: Robert Smalls, 1839-1915. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971. Essential Civil War Curriculum | Copyright 2020 Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech Page 1 of 2 Essential Civil War Curriculum | Ethan J. Kytle, Robert Smalls | September 2020 Organizations Web Resources Other Sources Scholars Name Email Ethan J. Kytle [email protected] Topic Précis Born into slavery in 1839 in Beaufort, South Carolina, Robert Smalls seized his and his family’s freedom by commandeering a Confederate ship, the Planter, in nearby Charleston in 1862. After sailing out of the city’s well-guarded harbor, Smalls surrendered the vessel to the Union fleet blockading Charleston, earning fame across the North and infamy across the South.