Foreign Clientelae in the Roman Empire Foreign Clientelae in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROMAN POLITICS DURING the JUGURTHINE WAR by PATRICIA EPPERSON WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State

ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR By PATRICIA EPPERSON ,WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State University Tahlequah, Oklahoma 1971 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1975 SEP Ji ·J75 ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR Thesis Approved: . Dean of the Graduate College 91648 ~31 ii PREFACE The Jugurthine War occurred within the transitional period of Roman politics between the Gracchi and the rise of military dictators~ The era of the Numidian conflict is significant, for during that inter val the equites gained political strength, and the Roman army was transformed into a personal, professional army which no longer served the state, but dedicated itself to its commander. The primary o~jec tive of this study is to illustrate the role that political events in Rome during the Jugurthine War played in transforming the Republic into the Principate. I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Neil Hackett, for his patient guidance and scholarly assistance, and to also acknowledge the aid of the other members of my counnittee, Dr. George Jewsbury and Dr. Michael Smith, in preparing my final draft. Important financial aid to my degree came from the Dr. Courtney W. Shropshire Memorial Scholarship. The Muskogee Civitan Club offered my name to the Civitan International Scholarship Selection Committee, and I am grateful for their ass.istance. A note of thanks is given to the staff of the Oklahoma State Uni versity Library, especially Ms. Vicki Withers, for their overall assis tance, particularly in securing material from other libraries. -

HCS — History of Classical Scholarship

ISSN: 2632-4091 History of Classical Scholarship www.hcsjournal.org ISSUE 1 (2019) Dedication page for the Historiae by Herodotus, printed at Venice, 1494 The publication of this journal has been co-funded by the Department of Humanities of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and the School of History, Classics and Archaeology of Newcastle University Editors Lorenzo CALVELLI Federico SANTANGELO (Venezia) (Newcastle) Editorial Board Luciano CANFORA Marc MAYER (Bari) (Barcelona) Jo-Marie CLAASSEN Laura MECELLA (Stellenbosch) (Milano) Massimiliano DI FAZIO Leandro POLVERINI (Pavia) (Roma) Patricia FORTINI BROWN Stefan REBENICH (Princeton) (Bern) Helena GIMENO PASCUAL Ronald RIDLEY (Alcalá de Henares) (Melbourne) Anthony GRAFTON Michael SQUIRE (Princeton) (London) Judith P. HALLETT William STENHOUSE (College Park, Maryland) (New York) Katherine HARLOE Christopher STRAY (Reading) (Swansea) Jill KRAYE Daniela SUMMA (London) (Berlin) Arnaldo MARCONE Ginette VAGENHEIM (Roma) (Rouen) Copy-editing & Design Thilo RISING (Newcastle) History of Classical Scholarship Issue () TABLE OF CONTENTS LORENZO CALVELLI, FEDERICO SANTANGELO A New Journal: Contents, Methods, Perspectives i–iv GERARD GONZÁLEZ GERMAIN Conrad Peutinger, Reader of Inscriptions: A Note on the Rediscovery of His Copy of the Epigrammata Antiquae Urbis (Rome, ) – GINETTE VAGENHEIM L’épitaphe comme exemplum virtutis dans les macrobies des Antichi eroi et huomini illustri de Pirro Ligorio ( c.–) – MASSIMILIANO DI FAZIO Gli Etruschi nella cultura popolare italiana del XIX secolo. Le indagini di Charles G. Leland – JUDITH P. HALLETT The Legacy of the Drunken Duchess: Grace Harriet Macurdy, Barbara McManus and Classics at Vassar College, – – LUCIANO CANFORA La lettera di Catilina: Norden, Marchesi, Syme – CHRISTOPHER STRAY The Glory and the Grandeur: John Clarke Stobart and the Defence of High Culture in a Democratic Age – ILSE HILBOLD Jules Marouzeau and L’Année philologique: The Genesis of a Reform in Classical Bibliography – BEN CARTLIDGE E.R. -

The Impossible Dream W. W. Tarn's Alexander in Retrospect*

F LASHBACKS Karanos 2, 2019 77-95 The Impossible Dream W. W. Tarn’s Alexander in Retrospect* by A. Brian Bosworth The University of Western Australia First published in 1948, Tarn’s Alexander the Great was soon out of print. In 1956 the first volume was republished in paperback under the auspices of Beacon Press in Boston, but the more substantial second volume remained inaccessible and was a collector’s item for decades. I myself had a standing order with Blackwell’s from 1967, but it was at the end of a long list and eventually after much persuasion I received personal permission to make my own photocopy of the work. At long last in 1979 both volumes were reissued in matching format, exact and uncorrected reprints of the original, and they are now available in Australia**. It must be said at once that it is twenty years too late. Virtually every major statement made by Tarn has been critically examined over the last two and a half decades and in almost every case rejected. His work on Alexander is now a historical curiosity, valuable as a document illustrating his own emotional and intellectual make-up but practically worthless as a serious history of the Macedonian conqueror. As will be seen, Tarn’s attitudes and methods are interesting in their own right, but they are not interesting enough to justify the outrageous and exorbitant price that is demanded of the Australian market. Hard pressed school librarians would make a far better investment by acquiring a range of more recent publications. -

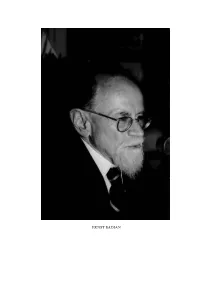

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011 THE ANCIENT HISTORIAN ERNST BADIAN was born in Vienna on 8 August 1925 to Josef Badian, a bank employee, and Salka née Horinger, and he died after a fall at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 1 February 2011. He was an only child. The family was Jewish but not Zionist, and not strongly religious. Ernst became more observant in his later years, and received a Jewish funeral. He witnessed his father being maltreated by Nazis on the occasion of the Reichskristallnacht in November 1938; Josef was imprisoned for a time at Dachau. Later, so it appears, two of Ernst’s grandparents perished in the Holocaust, a fact that almost no professional colleague, I believe, ever heard of from Badian himself. Thanks in part, however, to the help of the young Karl Popper, who had moved to New Zealand from Vienna in 1937, Josef Badian and his family had by then migrated to New Zealand too, leaving through Genoa in April 1939.1 This was the first of Ernst’s two great strokes of good fortune. His Viennese schooling evidently served Badian very well. In spite of knowing little English at first, he so much excelled at Christchurch Boys’ High School that he earned a scholarship to Canterbury University College at the age of fifteen. There he took a BA in Classics (1944) and MAs in French and Latin (1945, 1946). After a year’s teaching at Victoria University in Wellington he moved to Oxford (University College), where 1 K. R. Popper, Unended Quest: an Intellectual Autobiography (La Salle, IL, 1976), p. -

Tutorium Quercopolitanum

Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt Geschichts- und Gesellschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultät Lehrstuhl für Alte Geschichte TUTORIUM QUERCOPOLITANUM Ein althistorisches Proseminar © Andreas Hartmann, Eichstätt 10-2009 http://www.gnomon.ku-eichstaett.de/LAG/proseminar TUTORIUM QUERCOPOLITANUM – ANDREAS HARTMANN VORWORT 1 VORWORT Das vorliegende Tutorium hat eine komplexe Entstehungsgeschichte, die schon in sich ein ge- eignetes Objekt für „German Quellenforschung“ wäre: Bis vor etlichen Jahren wurde in den althistorischen Proseminaren an der Katholischen Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt ein „Alt- historisches Proseminarheft“ eingesetzt, das im Kern von Kai Brodersen für die Universitäten München bzw. Mannheim erstellt, dann von Beate Greif und vor allem Gregor Weber auf die Eichstätter Verhältnisse angepasst und aktualisiert wurde. Dieses Proseminarheft, das auch über Eichstätt hinaus eine sehr positive Resonanz erfahren hat, steht mittlerweile in einer aktualisierten Version auf den Seiten des Lehrstuhls für Alte Geschichte an der Universität Augsburg (http://www.philhist.uni-augsburg.de/lehrstuehle/geschichte/alte/links/Studienhilfe) zur Verfügung und wurde auch vom Seminar für Alte Geschichte der Universität Freiburg in geringfügig adaptierter Form übernommen (http://www.sag.uni-freiburg.de/materialien-zu- den-lehrveranstaltungen/proseminare/proseminarheft/view). Als der Autor im Wintersemester 2002/03 erstmals das Proseminar in Eichstätt durchführte, war zunächst daran gedacht, einfach das vorliegende „Proseminarheft“ dafür -

Illinois Classical Studies

immmmmu NOTICE: Return or renew alt Library Materials! The Minimum Fee for each Lost Book Is $50.00. The person charging this material is responsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for discipli- nary action and may result In dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN m •' 2m MAR1 m ' 9. 2011 m nt ^AR 2 8 7002 H«ro 2002 - JUL 2 2ii^ APR . -.^ art Ll( S~tH ^ v^ a ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XIX 1994 ISSN 0363-1923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XIX 1994 SCHOLARS PRESS ISSN 0363-1923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XIX Studies in Honor of Mirosiav Marcovich Volume 2 The Board of Trustees University of Illinois Copies of the journal may be ordered from: Scholars Press Membership Services P.O. Box 15399 Aaanta,GA 30333-0399 Printed in the U.S.A. EDITOR David Sansone ADVISORY EDITORIAL COMMITTEE William M. Calder IH J. K. Newman Eric Hostetter S. Douglas Olson Howard Jacobson Maryline G. Parca CAMERA-READY COPY PRODUCED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF MARY ELLEN FRYER Illinois Classical Studies is published annually by Scholars Press. Camera- ready copy is edited and produced in the Department of the Classics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Each contributor receives fifty offprints free of charge. Contributions should be addressed to: The Editor, Illinois Classical Studies Department of the Classics 4072 Foreign Languages Building 707 South Mathews Avenue Urbana, Illinois 61801 Miroslav Marcovich Doctor of Humane Letters, Honoris Causa The University of Illinois 15 May 1994 . -

Pleonexia, Parasitic Greed, and Decline in Greek Thought from Thucydides to Polybius

ABSTRACT Title of Document: HOW THINGS FALL APART: PLEONEXIA, PARASITIC GREED, AND DECLINE IN GREEK THOUGHT FROM THUCYDIDES TO POLYBIUS William D. Burghart, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Directed By: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Department of History This dissertation examines how Greek authors from the fifth to the second century BCE employed the concept of pleonexia to explain why cities lost power on the international stage and why they lost internal cohesion. First, it argues that Greek authors understood pleonexia to mean “the desire for more at the expense of another” as opposed simply “greed” as most modern authors translate it. Second, it contends that Greeks authors deployed the concept of pleonexia to describe situations that modern authors would describe as societal collapse—defined as the reduction of societal complexity, which can be measured through either the loss of material or immaterial means, e.g., land, wealth, political power, influence over others, political stability, or political autonomy. Greek authors used the language of pleonexia to characterize the motivation of an entity, either an individual within a community or a city or state, to act in a way that empowered the entity by taking or somehow depriving another similar entity of wealth, land, or power. In a city, pleonexia manifested as an individual seeking to gain power through discrediting, prosecuting, or eliminating rivals. In international affairs, it materialized as attempts of a power to gain more territory or influence over others. Acting on such an impulse led to conflict within cities and in the international arena. The inevitable result of such conflict was the pleonexic power losing more than it had had before. -

CU Classics Graduate Handbook

Graduate Handbook (CU Boulder, Classics) 1 Graduate Handbook University of Colorado Boulder Department of Classics Last updated: October 2018; minor corrections September 2020 Graduate Handbook (CU Boulder, Classics) 2 Contents Graduate Introduction .................................................................................................................... 4 M.A. Tracks.................................................................................................................................. 4 Ph.D. Track .................................................................................................................................. 4 Graduate Degrees in Classics .......................................................................................................... 5 Graduate Degrees and Requirements ........................................................................................ 5 Doctor of Philosophy in Classics ................................................................................................. 6 M.A. in Classics, with Concentration in Greek or Latin ............................................................... 8 M.A. in Classics, with Concentration in Classical Antiquity ........................................................ 9 M.A. in Classics, with Concentration in Classical Art and Archaeology .................................... 11 M.A. in Classics, with Concentration in the Teaching of Latin .................................................. 12 Ph.D. Requirements ..................................................................................................................... -

Schedule of Meetings for Affiliated Groups

144TH APA ANNUAL MEETING ABSTRACTS WASHINGTON STATE CONVENTION CENTER January 3-6, 2013 Seattle, WA ii PREFACE The abstracts in this volume appear in the form submitted by their authors without editorial intervention. They are arranged in the same order as the Annual Meeting Program. An index by name at the end of the volume is provided. This is the thirty first volume of Abstracts published by the Association in as many years, and suggestions of improvements in future years are welcome. Again this year, the Program Committee has invited affiliated groups holding sessions at the Annual Meeting to submit abstracts for publication in this volume. The following groups have published abstracts this year. AFFILIATED GROUPS American Association for Neo-Latin Studies American Classical League American Society of Greek and Latin Epigraphy American Society of Papyrologists Eta Sigma Phi Friends of Numismatics International Plutarch Society International Society for Neoplatonic Studies Lambda Classical Caucus Medieval Latin Studies Group Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Society for Ancient Medicine and Pharmacy Society for Ancient Mediterranean Religions Society for Late Antiquity Women’s Classical Caucus The Program Committee thanks the authors of these abstracts for their cooperation in making the timely production of this volume possible. 2012 ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM COMMITTEE MEMBERS Joseph Farrell, Chair Christopher A. Faraone Kirk Freudenburg Maud Gleason Corinne O. Pache Adam D. Blistein (ex officio) Heather H. Gasda (ex officio) iii iv -

SDSU Template, Version 11.1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CSUN ScholarWorks MOTIVES FOR ROMAN IMPERIALISM IN NORTH AFRICA, 300 BCE TO 100 CE _______________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of San Diego State University _______________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History _______________ by Michael A. DeMonto Summer 2015 iii Copyright © 2015 by Michael A. DeMonto All Rights Reserved iv DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Sara. Thank you for supporting my education venture for these past six years. Your love and support means everything to me. I love you! v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Motives For Roman Imperialism in North Africa, 300 BCE to 100 CE by Michael A. DeMonto Master of Arts in History San Diego State University, 2015 Previous examinations of Roman imperialism in North Africa are insufficient because they lack an appreciation of the balance between the defensive, political, and economic motives. These past arguments have focused on specific regions around the Mediterranean world, but have failed to include North Africa – an integral part of the Roman Empire. This region was politically and economically integrated into the empire during the first century CE. This study closely examines the ancient sources for Roman imperialism in North Africa from 300 BCE to 100 CE to construct the narrative for Roman imperialism while juxtaposing corresponding ancient and archaeological evidence. This study examines the ancient and modern constructed narratives against anthropological models for interstate warfare and cooperation. The ancient written sources include Polybius’s Histories, Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita and Periochae, Appian’s Roman History, Dio Cassius’s Roman History, Sallust’s Jugurthine War, Julius Caesar’s De Africo Bello, Velleius Paterculus’s Roman History, Augustus’s Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Tacitus’s Annals and Histories, and Pliny the Elder’s Natural Histories. -

Views of Rome in Athenian Inscriptions Connor Q

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Classics Honors Projects Classics Department Spring 4-23-2017 The oS vereign Ideal: Views of Rome in Athenian Inscriptions Connor Q. North [email protected], [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation North, Connor Q., "The oS vereign Ideal: Views of Rome in Athenian Inscriptions" (2017). Classics Honors Projects. 23. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors/23 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Sovereign Ideal: Views of Rome in Athenian Inscriptions By Connor Q. North Advised by Professor Beth Severy-Hoven Macalester College Classics Department Submitted April 23rd, 2017 N o r t h | 1 Chapter 1: Introduction At the peak of Athenian influence in the fifth century BCE its envoys addressed independent states in the same terms that the defeated Athens would later describe Rome.1 The course of events that led to the effective annexation of Athens in 27 BCE illustrates the gradual erosion of Athenian authority in easy contrast to the ascent of Rome; and yet, the rhetorical evidence that survives for us in the literary and epigraphic record reveals no such decline.2 Instead, -

Historische Literatur, 7. Band · 2009 · Heft 4 1 © Clio-Online – Historisches Fachinformationssystem E.V

Historisc e Literatur Band 7 · 2009 · Hef 4 Oktober – Dezember Rezensionszeitsc rif von IS N 1611-9509 H-Soz-u-Kult Veröff entlic ungen von Clio-online, Nr. 1 Cover_Bd7_1.indd 1 16.04.2010 14:32:40 Historische Literatur Rezensionszeitschrift von H-Soz-u-Kult Band 7 · 2009 · Heft 4 Veröffentlichungen von Clio-online, Nr. 1 Titelseiten_Bd7_1.indd 1 16.04.2010 14:40:45 Historische Literatur Rezensionszeitschrift von H-Soz-u-Kult Herausgegeben von der Redaktion H-Soz-u-Kult Geschäftsführende Herausgeber Rüdiger Hohls / Thomas Meyer / Claudia Prinz Technische Leitung Daniel Burckhardt / Kai Pätzke Titelseiten_Bd7_1.indd 2 16.04.2010 14:41:01 Historische Literatur Rezensionszeitschrift von H-Soz-u-Kult Band 7 · 2009 · Heft 4 Titelseiten_Bd7_1.indd 3 16.04.2010 14:41:01 Historische Literatur Rezensionszeitschrift von H-Soz-u-Kult Redaktionsanschrift H-Soz-u-Kult-Redaktion c/o Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Philosophische Fakultät I Institut für Geschichtswissenschaften Sitz: Friedrichstrasse 191-193 D-10099 Berlin Telefon: ++49-(0)30/2093-70602,-70605 und -70606 Telefax: ++49-(0)30/2093-70656 E-Mail: [email protected] www: http://hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de ISSN 1611-9509 Titelseiten_Bd7_1.indd 4 16.04.2010 14:41:01 Redaktion 1 Alte Geschichte 4 Birley, Anthony R.: The Roman Government of Britain. Oxford u.a. 2005. (Jorit Wintjes) 4 Burckhardt, Leonhard: Militärgeschichte der Antike. München 2008. (Andrea Schütze) 5 Griffin, Miriam (Hrsg.): A Companion to Julius Caesar. Oxford 2009. (Andreas Klingen- berg)............................................ 7 Gruen, Erich S. (Hrsg.): Cultural Borrowings and Ethnic Appropriations in Antiquity. Stuttgart 2005. (Ted Kaizer)..............................