Ghana's Police

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining the Urban Dimension of the Security Sector

Examining the Urban Dimension of the Security Sector Research Report Project Title: Providing Security in Urban Environments: The Role of Security Sector Governance and Reform Project supported by the Folke Bernadotte Academy (FBA) and the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) February 2018 Authors (in alphabetical order): Andrea Florence de Mello Aguiar, Lea Ellmanns, Ulrike Franke, Praveen Gunaseelan, Gustav Meibauer, Carmen Müller, Albrecht Schnabel, Usha Trepp, Raphaël Zaffran, Raphael Zumsteg 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents Authors Acknowledgements List of Abbreviations 1 Introduction: The New Urban Security Disorder 1.1 Puzzle and research problem 1.2 Purpose and research objectives 1.3 Research questions 1.4 Research hypotheses 1.5 Methodology 1.6 Outline of the project report 2 Studying the Security Sector in Urban Environments 2.1 Defining the urban context 2.2 Urbanisation trends 2.3 Urban security challenges 2.4 Security provision in urban contexts 2.5 The ‘generic’ urban security sector 2.6 Defining SSG and SSR: from national to urban contexts 3 The Urban SSG/R Context: Urban Threats and Urban Security Institutions 3.1 The urban SSG/R context: a microcosm of national SSG/R contexts 3.2 The urban environment: priority research themes and identified gaps 3.3 Excursus: The emergence of a European crime prevention policy 3.4 Threats prevalent and/or unique to the urban context – and institutions involved in threat mitigation 3.5 The urban security sector: key security, management and oversight institutions -

Ministry of the Interior

Republic of Ghana MEDIUM TERM EXPENDITURE FRAMEWORK (MTEF) FOR 2020-2023 MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR PROGRAMME BASED BUDGET ESTIMATES For 2020 Republic of Ghana MINISTRY OF FINANCE Responsive, Ethical, Ecient, Professional – Transforming Ghana Beyond Aid Finance Drive, Ministries-Accra Digital Address: GA - 144-2024 M40, Accra - Ghana +233 302-747-197 [email protected] mofep.gov.gh @ministryofinanceghana © 2019. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the Ministry of Finance On the Authority of His Excellency Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, President of the Republic of Ghana MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR i | 2020 BUDGET ESTIMATES The MoI MTEF PBB for 2020 is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh ii | 2020 BUDGET ESTIMATES Contents PART A: STRATEGIC OVERVIEW OF THE MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR .......... 2 1. MTDPF POLICY OBJECTIVES ........................................................................ 2 2. GOAL ............................................................................................................... 2 3. CORE FUNCTIONS ......................................................................................... 2 4. POLICY OUTCOME INDICATORS AND TARGETS ........................................ 3 5. EXPENDITURE TRENDS FOR THE MEDIUM-TERM ..................................... 4 6. SUMMARY OF KEY ACHIEVEMENTS IN 2019 ............................................. -

MINISTRY of the INTERIOR Management 45 47 53 53 55 55 Educational Letters Issued Institutions Greater Accra

Past Years Projections Output Republic of Ghana Main Outputs Budget Indicative Indicative Indicative Indicator 2017 2018 Year Year Year Year 2019 2020 2021 2022 Number of Audit of MMDAs Management 27 27 27 27 27 27 MEDIUM leTERMtters issued EXPENDITURE FRAMEWORK (MTEF) Number of Audit of MDA Management 275 280 360 360 375 375 Agencies FOR 2019-2022 letters issued Audit of Number of Traditional Management 5 5 15 15 15 15 Councils letters issued Audit of Pre- Number of tertiary MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR Management 45 47 53 53 55 55 Educational letters issued Institutions Greater Accra Region NuPROGRAMMEmber of BASED BUDGET ESTIMATES Audit of MMDAs Management 16 For16 20191 6 16 16 16 letters issued Number of Audit of MDA Management 146 150 170 170 190 190 Agencies letters issued Audit of Number of Traditional Management 5 5 6 6 6 6 Councils letters issued Audit of Pre- Number of tertiary Management 33 37 43 43 45 45 Educational letters issued Institutions Central Region Number of Audit of MMDAs Management 20 20 20 20 20 20 letters issued Number of Audit of MDA Management 198 200 260 260 265 265 Agencies letters issued Audit of Number of Traditional Management 5 5 15 15 15 15 Councils letters issued Audit of Pre- Number of tertiary Management 63 62 75 75 70 70 Educational letters issued Institutions Western Region On the Authority of His Excellency Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, 22 | President of the Republic of Ghana 2019 BUDGET ESTIMATES i | 2019 BUDGET ESTIMATES MINISTRY OFPast Yea rTHEs INTERIORProjections Output Main Outputs Budget Indicative -

UN Police Magazine 8

8th edition, January 2012 MAGAZINE United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations asdf Sustainable Peace through Justice and Security January 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 8th Edition [ INTRODUCTION ] [ BUILDING NATIONAL CAPACITY ] 1 ] United Nations Police Play an Invaluable Role 8 ] Peace: Keep it. Build it. Ban Ki-moon, United Nations Secretary-General Dmitry Titov, Assistant Secretary-General Office of 2 ] Helping to Build Accountable Police Services Rule of Law and Security Institutions, Hervé Ladsous, Under-Secretary-General Department of Peacekeeping Operations Department of Peacekeeping Operations 5 ] UN Policing 3 ] Professionalism: UN Policing 2012 6 ] Côte D’Ivoire Ann-Marie Orler, United Nations Police Adviser 7 ] Democratic Republic of the Congo 9 ] Haiti [ UNITED NATIONS GLOBAL EFFORT ] 12 ] Liberia 13 ] South Sudan 20 ] International Network of Female Police 17 ] Special Political Missions Peacekeepers launched at IAWP 24 ] International Female Police Peacekeeper Award 2011 26 ] Sexual and Gender Based Violence Training [ FACTS & FIGURES ] 19 ] Top Ten Contributors of UN Police [ POLICE DIVISION ] 22 ] Actual/Authorized/Female Deployment of UN Police in Peacekeeping Missions 28 ] Consolidating Formed Police Units 27 ] Top Ten Contributors of Female UN 29 ] UNPOL and Interpol: Global Partnership Police Officers 31 ] All Points Bulletin 37 ] FPU Deployment 32 ] Policiers Francophones l’ONU a besoin de vous ! 38 ] UN Police Contributing Countries (PCCs) 33 ] Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie 39 ] Police Division Staff 36 ] Harnessing Technology for Efficiency Photo caption: UN and PNTL officers conducting a foot 37 ] Deputy Police Adviser Shoaib Dastgir patrol on market day in Atauro, Timor-Leste. (UN Photo/Martine Perret) Cover illustration: Conor Hughes/United Nations PROFESSIONAL Service – LASTING IMPACT UNITED NATIONS POLICE PLAY AN INVALUABLE ROLE Since UN Police are typically deployed into situ- Garten) (UN Photo/Mark Ban Ki-moon. -

International Responses to Human Trafficking: the Ghanaian Experience

Vol.7(7), pp. 62-68, November 2016 DOI: 10.5897/IJPDS2016.0282 Article Number: B02B4AF61520 International Journal of Peace and Development ISSN 2141–6621 Copyright © 2016 Studies Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJPDS Full Length Research Paper International responses to human trafficking: The Ghanaian experience Gerald Dapaah Gyamfi University of Professional Studies, Accra, Ghana . Recieved 14 September, 2016; Accepted 26 October, 2016 Human trafficking in this era has been conceptualized as a global event that is likened to slavery because of the inhumane treatment that the victims go through. The scope and the criminal aspect of it demands police initiative to curb the menace. The current researcher used semi-structured qualitative interview, direct observation, and review of documents to gather data from Ghana Police Service and some anti-human trafficking institutions in Ghana to identify the nature, scope and responses to reduce or eradicate this menace that has detrimental effect on the people of Ghana, as a case study. Contemporarily, in terms of origin, destination and transit of people to engage in this criminal act, the menace put Ghana into Tier Two Watch-List classification in 2015 on the international level. Human trafficking in Ghana was characterized as violence, debt bondage, exploitation, deprivation of the freedom of the victims, and confiscation of travelling and other documents. The study revealed that the government of Ghana had put in only a minimal effort to curb the menace, and that the trafficking of people had created a security concern that the police must be apt to control. -

Ghana Police Service

Published by: Global Facilitation Network for Security Sector Reform University of Cranfield Shrivenham, UK ISSN 1740-2425 Volume 4 Number 2 - April 2006 An Overview Of The Ghana Police Service Emmanuel Kwesi Aning Acknowledgements In the preparation of this paper, several individuals and organisations have given support. Let me first thank Prosper Nii Nortey Addo, a Researcher at the African Security Dialogue and Research, who was instrumental in tracking down rare documents and setting up meetings with key officials. Probably, this work could not have been completed on time but for the consistent interest and support of two key Police officers whose personal and professional support disproves the generally held negative public view of the Police. Heartfelt thanks for DSP Paul Avuyi who took time off his busy schedule to talk and patiently ask questions. His personal interest in the work did not only end with his intellectual input, he carefully read the work and made suggestions. From the Records and Archival Department, thanks to Michael Teku for providing documents, the state of which definitely demonstrate the need for proper storage and care. There are several individuals who for several reasons want to remain unmentioned. They were instrumental in providing documents relevant to the study and sharing diverse perspectives on the Police, which has gone to enrich this short paper. The genesis of this short paper can be located within two totally separate but linked projects. One was the initiation of a study of public perceptions of the police by the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA) and a conference on Police and Policing in Ghana organised by the African Security Dialogue and Research (ASDR) in conjunction with MFWA and the Ministry of Interior. -

Leph2018 Program

MONDAY 22 OCTOBER LEPH2018 PROGRAM 8:30-10:00 a.m. PLENARY SESSION P1 Room: Ballroom East and Center Chair: Nick Crofts, LEPH2018 Conference Director & Director, Centre for Law Enforcement and Public Health Speakers: • Nick Crofts, see above Welcome to the LEPH2018 Conference • Howard Sapers, Independent Advisor on Corrections Reform, Ontario, Canada Prison health IS public health • Charles H Ramsey, Philadelphia Police Commissioner, USA (ret) Police, crisis intervention and officer well being • Shannon Cosgrove, Director of Health Policy at Cure Violence, USA Health at the center of violence prevention 10.00 – 10.30 MORNING TEA 10:30-11:55 MAJOR SESSIONS M1 The Crisis Intervention Team Model: What we have learned after 30 years The Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) model was developed 30 years ago in Memphis, Tennessee. There is now a growing body of research evidence on it’s effectiveness. However, there remains some confusion about the model. This session will discuss the Core Elements of the CIT model and what is meant by "more than just training." Community collaboration, a responsive mental health system and the specialized CIT officer role will be covered. Room: Ballroom East Chair: Tom VonHemert, CIT International, USA Speakers: Amy Watson, University of Illinois Chicago, USA CIT – The evidence to date Don Kamin, Institute for Police, Mental Health & Community Collaboration, USA & Pat Strode, Georgia Public Safety Training Center, USA Perspectives on developing and implementing CIT programs – collaboration is key Ron Bruno, CIT Utah, USA The core elements of the CIT model – the “More” explained and why it matters Thomas Vonhemert, CIT International, USA The CIT Model: what have we learned after 30 years 1 MONDAY 22 OCTOBER M2 Public health and policing in England: an opportunity to improve health through partnership Working in partnership is essential if we are to address the ‘causes of the causes’ which lead people into contact with the police. -

OCCUPATIONAL FRAUD: a Comparative Study of Ghana and Nigeria

Institute of Criminal Justice Studies OCCUPATIONAL FRAUD: A Comparative Study of Ghana and Nigeria MICHELLE ODUDU BA, MSc The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth Submitted 31 Oct 2017 WHILST REGISTERED AS A CANDIDATE FOR THE ABOVE DEGREE, I HAVE NOT BEEN REGISTERED FOR ANY OTHER RESEARCH AWARD. THE RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS EMBODIED IN THIS THESIS ARE THE WORK OF THE NAMED CANDIDATE AND HAVE NOT BEEN SUBMITTED FOR ANY OTHER ACADEMIC AWARD i Abstract Ghana and Nigeria are known for their high levels of Occupational Fraud in public offices. The governments of both countries have emphasised their commitment to reducing the losses caused to the state by pledging their allegiance to the counter fraud agencies to help tackle Occupational Fraud. Yet it seems that the prosecution of such cases are ineffective as high-profile fraudsters can operate with immunity and their cases remain unprosecuted. This research project was based on in-depth examinations of 50 occupational fraud cases, involving high profile individuals in both countries. In doing so, it established the characteristics of those who were prosecuted; the extent to which prosecutions were effectively managed; the barriers to effective prosecutions; and the similarities or differences between the occurrences in both countries. The aim of the project is to examine the practice of, and barriers to prosecution of large scale occupational fraud of those in senior public positions in Ghana and Nigeria. The study drew on the experiences of stakeholders such as defence and prosecution barristers, academics and fraud analysts via semi- structured interviews and questionnaires. -

Downloads/RHM%20Article.Pdf)

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details MAKING A DIFFERENCE: A STUDY OF THE ‘SOCIAL MARKETING’ CAMPAIGN IN AWARENESS CREATION OF GENDER BASED VIOLENCE IN GHANA MARIAN TSEGAH THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF D.PHIL UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX DECEMBER 2015 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signed Marian Tsegah iii UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX MARIAN TSEGAH DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY MAKING A DIFFERENCE: A STUDY OF THE ‘SOCIAL MARKETING’ CAMPAIGN IN AWARENESS CREATION OF GENDER BASED VIOLENCE IN GHANA SUMMARY Within feminist scholarship advertising – representing women as wives, mothers and sexual objects – has long been regarded as patriarchal, blocking women’s liberation (Talbot 2000) and thus an impossible practice for progressive activism. More recently, however, approaches acknowledge advertising as a ‘tool’ deployed for a range of ‘political’ ends, encouraging changes in values, understandings and behaviors. Such advertising is often referred to as ‘social marketing’. -

Ghana Police Service Standard Operating Procedures

Ghana Police Service Standard Operating Procedures GHANA POLICE SERVICE (LEGAL AND PROSECUTIONS Page 1 of 1 DIRECTORATE) SUBJECT: CODE OF CONDUCT NUMBER: GPS - SP001-15 EFFECTIVE DATE: REVIEW DATE: AMENDS/SUPERSEDES: APPROVED: 1. POLICY 1.1. Police officers shall at all times act impartially and in accordance with existing laws, which must be enforced on all persons without discrimination. 1.2. Police officers shall respect and protect human dignity, maintain and uphold rights of all persons. 1.3. Police officers shall perform their duties without partiality and discrimination to all persons. 1.4. Police officers shall treat suspects as innocent persons, politely, respectfully and professionally. 1.5. Police officers shall respect and uphold the rule of law. 1.6. Police officers shall ensure that they treat all persons in a courteous manner and that their conduct is exemplary and consistent with the demands of the profession and the public they serve. 1 | P a g e GHANA POLICE SERVICE (LEGAL AND PROSECUTIONS Page 1 of 1 DIRECTORATE) SUBJECT: PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATIONS NUMBER: GPS - SP002-15 EFFECTIVE DATE: REVIEW DATE: AMENDS/SUPERSEDES: APPROVED: 1. PURPOSE This standard operating procedure provides guidelines for Police personnel in conducting preliminary investigations. 2. PROCEDURE 2.1. If there are reasonable grounds to suspect that a crime has been committed or is about to be committed, the police must take the steps necessary; 2.1.1. To identify and arrest the perpetrator(s) of the crime 2.1.2. To prevent the perpetrator or accomplice from absconding 2.1.3. To detect and secure all material and documentary evidence relating to the crime, which might serve as evidence 2.1.4. -

Iacp New Members

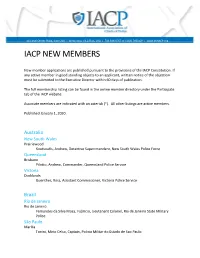

44 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 200 | Alexandria, VA 22314, USA | 703.836.6767 or 1.800.THEIACP | www.theIACP.org IACP NEW MEMBERS New member applications are published pursuant to the provisions of the IACP Constitution. If any active member in good standing objects to an applicant, written notice of the objection must be submitted to the Executive Director within 60 days of publication. The full membership listing can be found in the online member directory under the Participate tab of the IACP website. Associate members are indicated with an asterisk (*). All other listings are active members. Published January 1, 2020. Australia New South Wales Prairiewood Koutsoufis, Andrew, Detective Superintendent, New South Wales Police Force Queensland Brisbane Pilotto, Andrew, Commander, Queensland Police Service Victoria Docklands Guenther, Ross, Assistant Commissioner, Victoria Police Service Brazil Rio de Janeiro Rio de Janeiro Fernandes da Silva Moca, Fabricio, Lieutenant Colonel, Rio de Janeiro State Military Police São Paulo Marilia Tonini, Mirio Celso, Captain, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Piracicaba Gonzales, Pablo, Captain, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Sao Paulo de Godoy, Flavia Feliciano, CB PM, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo de Mendonca, Fabiano Soares, Captain, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Kitsuwa, Mario, Major, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Rodrigues Rosa, Hudson Arthur, Captain, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Canada Alberta Calgary *Barrett, Nicole, Sergeant, Calgary Police Service -

CTS Brochure May 2010 Aman:Layout 1

Understand the threat….reduce the risk Enhancing our knowledge of how and why Course commences terrorists plot against their targets makes a 5th May 2010 “ huge difference to our security strategy Andy Blackwell, Head of Aviation Security, Enrolling Now Virgin Atlantic Airways ” Further intakes commence 13th September 2010 17th January 2011 Advance registrations being accepted 16 week Approved by MoD in support of the ELC Scheme online course Provider number 2035 Course Programme: Core Module (compulsory) • Key Issues in International Terrorism Elective Modules • Terrorist Ideologies, Aims, Beliefs and Motivations • Terrorist Modus Operandi • International Policing Policy • Introduction to Aviation Terrorism and Security • Introduction to Maritime Terrorism and Security Supported by www.terrorismstudies.com ACPO TAM [email protected] +44 (0)20 3377 3210 (UK) +1 (646) 957 8929 (North America) This brochure has been produced using environmentally friendly paper sourced from sustainable forests and is chlorine free “”The need for businesses to understand and meet the threats has never been greater Dear Colleague, Why study by distance If it's part of your responsibility to protect people, infrastructure, organisations or learning? investments, you need to understand the threats, then prepare and implement best practice strategies to reduce risk. • Access the course whenever and wherever you have internet access Established in September 2006, in partnership with Informa, our Certificate in Terrorism Studies is the first transnational e-learning course to provide individuals, • Benefit from having access to the world’s military, and police, as well as public and private sector organisations with an leading experts at the touch of a button understanding of the latest thinking on terrorism.