The Chinese As Railroad Workers After Promontory”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limited Horizons on the Oregon Frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the Town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 Limited horizons on the Oregon frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890 Richard P. Matthews Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Matthews, Richard P., "Limited horizons on the Oregon frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3808. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5692 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Richard P. Matthews for the Master of Arts in History presented 4 November, 1988. Title: Limited Horizons on the Oregon Frontier: East Tualatin Plains and the Town of Hillsboro, Washington county, 1840 - 1890. APPROVED BY MEMBE~~~ THESIS COMMITTEE: David Johns n, ~on B. Dodds Michael Reardon Daniel O'Toole The evolution of the small towns that originated in Oregon's settlement communities remains undocumented in the literature of the state's history for the most part. Those .::: accounts that do exist are often amateurish, and fail to establish the social and economic links between Oregon's frontier towns to the agricultural communities in which they appeared. The purpose of the thesis is to investigate an early settlement community and the small town that grew up in its midst in order to better understand the ideological relationship between farmers and townsmen that helped shape Oregon's small towns. -

Transcontinental Railways and Canadian Nationalism Introduction Historiography

©2001 Chinook Multimedia Inc. Page 1 of 22 Transcontinental Railways and Canadian Nationalism A.A. den Otter ©2001 Chinook Multimedia Inc. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication or distribution is strictly prohibited. Introduction The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) has always been a symbol of Canada's nation-building experience. Poets, musicians, politicians, historians, and writers have lauded the railway as one of the country's greatest achievements. Indeed, the transcontinental railway was a remarkable accomplishment: its managers, engineers, and workers overcame incredible obstacles to throw the iron track across seemingly impenetrable bogs and forests, expansive prairies, and nearly impassable mountains. The cost in money, human energy, and lives was enormous. Completed in 1885, the CPR was one of the most important instruments by which fledgling Canada realized a vision implicit in the Confederation agreement of 1867-the building of a nation from sea to sea. In the fulfilment of this dream, the CPR, and subsequently the Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk systems, allowed the easy interchange of people, ideas, and goods across a vast continent; they permitted the settlement of the Western interior and the Pacific coast; and they facilitated the integration of Atlantic Canada with the nation's heartland. In sum, by expediting commercial, political, and cultural intercourse among Canada's diverse regions, the transcontinentals in general, and the CPR in particular, strengthened the nation. Historiography The first scholarly historical analysis of the Canadian Pacific Railway was Harold Innis's A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway. In his daunting account of contracts, passenger traffic, freight rates, and profits, he drew some sweeping conclusions. -

Historic P U B Lic W Ork S P Roje Cts on the Ce N Tra L

SHTOIRICHISTORIC SHTOIRIC P U B LIC W ORK S P ROJE TSCP ROJE CTS P ROJE TSC ON THE CE N TRA L OCA STCOA ST OCA ST Compiled by Douglas Pike, P.E. Printing Contributed by: Table of Contents Significant Transportation P rojects......2 El Camino Real................................................... 2 US Route 101...................................................... 3 California State Route 1...................................... 6 The Stone Arch Bridge ..................................... 11 Cold Spring Canyon Arch Bridge..................... 12 Significant W ater P rojects...................14 First Dams and Reservoirs................................ 14 First Water Company........................................ 14 Cold Spring Tunnel........................................... 15 Mission Tunnel ................................................. 16 Gibraltar Dam ................................................... 16 Central Coast Conduit....................................... 18 Water Reclamation In Santa Maria Valley....... 23 Twitchell Dam & Reservoir.............................. 24 Santa Maria Levee ............................................ 26 Nacimiento Water Project................................. 28 M iscellaneous P rojects of Interest.......30 Avila Pier .......................................................... 30 Stearns Wharf.................................................... 32 San Luis Obispo (Port Harford) Lighthouse..... 34 Point Conception Lighthouse............................ 35 Piedras Blancas Light ...................................... -

X********X************************************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made * from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 302 264 IR 052 601 AUTHOR Buckingham, Betty Jo, Ed. TITLE Iowa and Some Iowans. A Bibliography for Schools and Libraries. Third Edition. INSTITUTION Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 312p.; Fcr a supplement to the second edition, see ED 227 842. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibllographies; *Authors; Books; Directories; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; History Instruction; Learning Resources Centers; *Local Color Writing; *Local History; Media Specialists; Nonfiction; School Libraries; *State History; United States History; United States Literature IDENTIFIERS *Iowa ABSTRACT Prepared primarily by the Iowa State Department of Education, this annotated bibliography of materials by Iowans or about Iowans is a revised tAird edition of the original 1969 publication. It both combines and expands the scope of the two major sections of previous editions, i.e., Iowan listory and literature, and out-of-print materials are included if judged to be of sufficient interest. Nonfiction materials are listed by Dewey subject classification and fiction in alphabetical order by author/artist. Biographies and autobiographies are entered under the subject of the work or in the 920s. Each entry includes the author(s), title, bibliographic information, interest and reading levels, cataloging information, and an annotation. Author, title, and subject indexes are provided, as well as a list of the people indicated in the bibliography who were born or have resided in Iowa or who were or are considered to be Iowan authors, musicians, artists, or other Iowan creators. Directories of periodicals and annuals, selected sources of Iowa government documents of general interest, and publishers and producers are also provided. -

Filumena and the Canadian Identity a Research Into the Essence of Canadian Opera

Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final thesis for the Bmus-program Icelandic Academy of the Arts Music department May 2020 Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final Thesis for the Bmus-program Supervisor: Atli Ingólfsson Music Department May 2020 This thesis is a 6 ECTS final thesis for the B.Mus program. You may not copy this thesis in any way without consent from the author. Abstract In this thesis I sought to identify the essence of Canadian opera and to explore how the opera Filumena exemplifies that essence. My goal was to first establish what is unique about Canadian opera. To do this, I started by looking into the history of opera composition and performance in Canada. By tracing these two interlocking histories, I was able to gather a sense of the major bodies of work within the Canadian opera repertoire. I was, as well, able to deeper understand the evolution, and at some points, stagnation of Canadian opera by examining major contributing factors within this history. My next steps were to identify trends that arose within the history of opera composition in Canada. A closer look at many of the major works allowed me to see the similarities in terms of things such as subject matter. An important trend that I intend to explain further is the use of Canadian subject matter as the basis of the operas’ narratives. This telling of Canadian stories is one aspect unique to Canadian opera. -

Asian Heritage Month Festival 2018 Concert Artists

Asian Heritage Month Festival 2018 Concert and Arts Showcase Artistic Directors Chan Ka Nin Chan Ka Nin is a distinguished Canadian composer whose extensive repertoire draws on both East and West in its aesthetic outlook. Professor of Theory and Composition at the University of Toronto, he has written in most musical genres and received many national and international prizes, including two JUNO awards, the Jean A. Chalmers Award, the Béla Bartók International Composers' Competition in Hungary, and the Barlow International Competition in the United States. In 2001 he won the Dora Mavor Moore Award for Outstanding Musical for his opera Iron Road, written with librettist Mark Brownell, depicting the nineteenth century construction of the Canadian National Railway by Chinese migrant labourers. Characteristically luminous in texture and exotic in instrumental colours, Prof. Chan's music has been described by critics as "sensuous," "haunting" and "intricate." The composer often draws his inspiration directly from his personal experiences: for example, the birth of one of his daughters, the death of his father, his spiritual quests, or his connection to nature and concern for the environment. Many prominent ensembles and soloists have performed his music, including the Toronto Symphony, National Arts Centre Orchestra, Hong Kong Philharmonic, Calgary Philharmonic, Nova Scotia Symphony, Esprit Orchestra, Manitoba Chamber Orchestra, Amici Ensemble, Gryphon Trio, Miró Quartet, St. Lawrence Quartet, Purcell Quartet, Amherst Saxophone Quartet, violist Rivka Golani, and oboist Lawrence Cherney. His substantial discography includes releases on the CBC, Centrediscs, ATMA, Analekta, Albany, and Summit labels, among others. Born and raised in Hong Kong, Mr. Chan holds twin undergraduate degrees in electrical engineering and music from the University of British Columbia, where he studied composition with Jean Coulthard. -

Catellus Development Corporation Railroad Land Grant Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c89g5tqc No online items Catellus Development Corporation railroad land grant records Finding aid created by California State Railroad Museum Library and Archives staff using RecordEXPRESS California State Railroad Museum Library and Archives 111 I Street Sacramento, California 95814 (916) 323-8073 [email protected] http://csrmf.org/visit/library 2020 Catellus Development MS 634 1 Corporation railroad land grant records Descriptive Summary Title: Catellus Development Corporation railroad land grant records Dates: 1852-1982 Collection Number: MS 634 Creator/Collector: Catellus Development Corporation Extent: 243 linear feet Repository: California State Railroad Museum Library and Archives Sacramento, California 95814 Abstract: This collection includes land grant records from the Catellus Development Corporation, a holding company created in 1986 to manage Southern Pacific's California real estate holdings . This collection documents federal land grants to the Southern Pacific Railroad, Central Pacific, and other subsidiary and predecessor railroads through a series of Pacific Railway Acts from the 1860s to the 1880s. Language of Material: English Access Collection is open for research by appointment. Please contact CSRM Library staff for details. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the California State Railroad Museum. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Librarian. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the CSRM as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained by the reader. Preferred Citation Catellus Development Corporation railroad land grant records. -

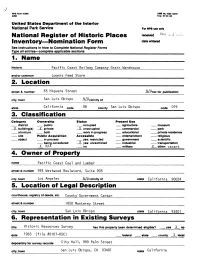

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

•V NFS Form 10-900 OMB No.1024-0018 (342) Exp. 1O-31-84 For NFS UM only National Register of Historic Places received /V|Ar - Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Pacific Coast Railway Company Grain Warehouse and/or common Loomis Feed Store 2. Location street & number 65 Higuera Street N/Anot for publication city, town San Luis Obispo vicinity of state California code 06 county San Luis Obispo code 079 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum _X_ building(s) X private _ X_ unoccupied __ commercial __ park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation X N/A no military _X__ other: vacant 4. Owner of Property name Pacific Coast Coal and Lumber street & number 924 Westwood Boulevard, Suite 905 city, town Los Angeles JU/A vicinity of state California 90024 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. County Government Center street & number 1050 Monterey Street city, town San Luis Obispo state California 93401 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic Resources Survey has this property been determined eligible? ., yes X, no date 1983 (file #0107-05C) federal state __ county —X_ local depository for survey records Clty Ha11 * "° Pa1m Street city, town San Luis Obispo, CA 93401 state California 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered X original site __ good __ ruins X altered __ moved date X fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The warehouse is a long, gable-roofed late Nineteenth Century trackside structure; light wood frame with corrugated iron panels covering both roofs and walls. -

Downloading a Copy to Your Computer

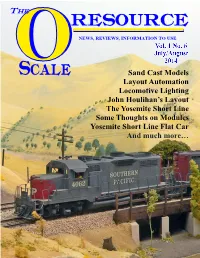

OO NEWS, REVIEWS, INFORMATION TO USE Sand Cast Models Layout Automation Locomotive Lighting John Houlihan’s Layout The Yosemite Short Line Some Thoughts on Modules Yosemite Short Line Flat Car And much more… The O Scale Resource July/August 2014 1 Bill Of Lading 2 Table of contents Published Bi Monthly 3 Editorial comment 4 News and Reviews The Model Railroad Resource LLC 8 Sand Cast Models Plymouth, Wisconsin A look at how some of the O Scale models were made Editors 25 The Yosemite Short Line Glenn Guerra A sectional modular club layout [email protected] 37 Yosemite Short Line Flat Car Dan Dawdy Some information and drawings of the last remaining car [email protected] 44 The John Hammond Car Company A brief synopsis Copy Editor 45 Looking at Layout Automation Amy Dawdy Accessory (turnout) decoders 53 John Houlihan’s Layout July-August 2014 A look at John’s layout past and present Vol 1 #6 62 Locomotive Lighting Using MV lenses Welcome to the online O Scale Resource magazine. The magazine is presented in an easy 67 Some Thoughts on Modules to use format. The blue bar above the magazine A look at some different ideas on modules has commands for previewing all the pages, advancing the pages forwards or back, searching 76 O Scale Shows & Meets to go to a specific page, enlarging pages, printing pages, enlarging the view to full screen, and 77 The O Scale Resource Classifieds downloading a copy to your computer. Front Cover Photo A Souther Pacific local freight heads up into the Tehachapi mountains on John Houlihan’s layout Advertisers Index Alleghyeney Scale Models Pg 52 Korber Models Pg 52 Altoona Model Works Pg 66 P & D Hobby Shop Pg 66 Rear Cover Photo BTS Pg 24 Rich Yoder Models Pg 44 Clover House Pg 52 San Juan Car company Pg 66 Crow River Models Pg 44 SMR Trains Pg 52 Small town on the Yosemite Short Delta Models Pg 24 Stevenson Preservation Lines Pg 66 Line Railroad. -

Northern Ohio Railway Museum Used Book Web Sale

NORTHERN OHIO RAILWAY MUSEUM USED BOOK 6/9/2021 1 of 20 WEB SALE No Title Author Bind Price Sale 343 100 Years of Capital Traction King Jr., Leroy O. H $40.00 $20.00 346026 Miles To Jersey City Komelski, Peter L. S $15.00 $7.50 3234 30 Years Later The Shore Line Carlson, N. S $10.00 $5.00 192436 Miles of Trouble Morse, V.L S $15.00 $7.50 192536 Miles of Trouble revised edition Morse, V.L. S $15.00 $7.50 1256 3-Axle Streetcars vol. 1 From Robinson to Rathgeber Elsner, Henry S $20.00 $10.00 1257 3-Axle Streetcars vol. 2 From Robinson to Rathgeber Elsner, Henry S $20.00 $10.00 1636 50 Best of B&O Book 3 50 favorite photos of B&O 2nd ed Kelly, J.C. S $20.00 $10.00 1637 50 Best of B&O Book 5 50 favorite photos of B&O Lorenz, Bob S $20.00 $10.00 1703 50 Best of PRR Book 2 50 favorite photos of PRR Roberts, Jr., E. L. S $20.00 $10.00 2 Across New York by Trolley QPR 4 Kramer, Frederick A. S $10.00 $5.00 2311Air Brake (New York Air Brake)1901, The H $10.00 $5.00 1204 Albion Branch - Northwestern Pacific RR Borden, S. S $10.00 $5.00 633 All Aboard - The Golden Age of American Travel Yenne, Bill, ed. H $20.00 $10.00 3145 All Aboard - The Story of Joshua Lionel Cowan Hollander, Ron S $10.00 $5.00 1608 American Narrow Gauge Railroads (Z) Hilton, George W. -

Amtrak Multiple Passenger Train Routes Crossing Montana: Are They Needed? Angelo Rosario Zigrino the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 1972 Amtrak multiple passenger train routes crossing Montana: Are they needed? Angelo Rosario Zigrino The University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Recommended Citation Zigrino, Angelo Rosario, "Amtrak multiple passenger train routes crossing Montana: Are they needed?" (1972). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 7979. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/7979 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMTRAK MULTIPLE PASSENGER TRAIN ROUTES CROSSING MONTANA* ARE THEY NEEDED? By Angelo R. Zigrino B.S., University of Tennessee, I9 6 I Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Business Administration UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1972 proved\byi 3 Chair: Board of Examiners Da Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EP38780 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI PMsIishing UMI EP38780 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

TKE HISTORY of TKE PORT of COOS BAY a Thesis Presented To

TKE HISTORY OF TKE PORT OF COOS BAY 1852 -1952 George Baxter Case, A.A., B.A. A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Pan American University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Pan American Universitir Edinburg , Texas August 1983 THE HISTORY OF THE PORT OF COOS BAY 1852-1952 / - 4 &,dL;' d/: /i~Cetrzd,Jf-~ (COMMITTEE MEMBER) DATE: O& ro.19 8.3 DL4 (DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SC by George Baxter Case PREFACE This is a study of commercial growth in the Coos Bay, Oregon region and of the physical improvements to the Port of Coos Bay which accompanied that growth during the one hundred years following modem settlement. The history of industrial development at Coos Ray has been shaped by the abundant natural resources found there and by the geographical isolation of the area. The Port of Coos Bay has been the primary means by which that isolation has been relieved and through which those resources have been marketed. Although a considerable body of literature about Coos Bay exists, no previous work deals solely with the economic development of the region as it relates to the improvements to the port. This study attempts to show not only the chronology of events during the period, but also the relationship between the commercial growth of the region and the zovernmental improvements to the port which followed and paralleled that growth. At least two masters' theses deal with Coos Bay: John Rudolph Feichtinger's "A Geographic Study of the City of Coos Bay and Its interl land" (University of Oregon, 1950), and Robert E.