The Railroads and San Luis Obispoâ•Žs Urban Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic P U B Lic W Ork S P Roje Cts on the Ce N Tra L

SHTOIRICHISTORIC SHTOIRIC P U B LIC W ORK S P ROJE TSCP ROJE CTS P ROJE TSC ON THE CE N TRA L OCA STCOA ST OCA ST Compiled by Douglas Pike, P.E. Printing Contributed by: Table of Contents Significant Transportation P rojects......2 El Camino Real................................................... 2 US Route 101...................................................... 3 California State Route 1...................................... 6 The Stone Arch Bridge ..................................... 11 Cold Spring Canyon Arch Bridge..................... 12 Significant W ater P rojects...................14 First Dams and Reservoirs................................ 14 First Water Company........................................ 14 Cold Spring Tunnel........................................... 15 Mission Tunnel ................................................. 16 Gibraltar Dam ................................................... 16 Central Coast Conduit....................................... 18 Water Reclamation In Santa Maria Valley....... 23 Twitchell Dam & Reservoir.............................. 24 Santa Maria Levee ............................................ 26 Nacimiento Water Project................................. 28 M iscellaneous P rojects of Interest.......30 Avila Pier .......................................................... 30 Stearns Wharf.................................................... 32 San Luis Obispo (Port Harford) Lighthouse..... 34 Point Conception Lighthouse............................ 35 Piedras Blancas Light ...................................... -

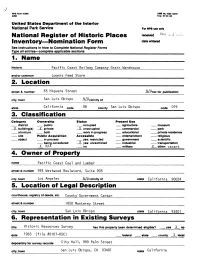

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

•V NFS Form 10-900 OMB No.1024-0018 (342) Exp. 1O-31-84 For NFS UM only National Register of Historic Places received /V|Ar - Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Pacific Coast Railway Company Grain Warehouse and/or common Loomis Feed Store 2. Location street & number 65 Higuera Street N/Anot for publication city, town San Luis Obispo vicinity of state California code 06 county San Luis Obispo code 079 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum _X_ building(s) X private _ X_ unoccupied __ commercial __ park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation X N/A no military _X__ other: vacant 4. Owner of Property name Pacific Coast Coal and Lumber street & number 924 Westwood Boulevard, Suite 905 city, town Los Angeles JU/A vicinity of state California 90024 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. County Government Center street & number 1050 Monterey Street city, town San Luis Obispo state California 93401 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic Resources Survey has this property been determined eligible? ., yes X, no date 1983 (file #0107-05C) federal state __ county —X_ local depository for survey records Clty Ha11 * "° Pa1m Street city, town San Luis Obispo, CA 93401 state California 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered X original site __ good __ ruins X altered __ moved date X fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The warehouse is a long, gable-roofed late Nineteenth Century trackside structure; light wood frame with corrugated iron panels covering both roofs and walls. -

Downloading a Copy to Your Computer

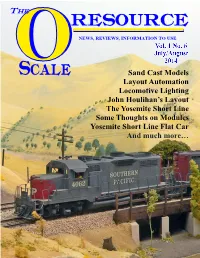

OO NEWS, REVIEWS, INFORMATION TO USE Sand Cast Models Layout Automation Locomotive Lighting John Houlihan’s Layout The Yosemite Short Line Some Thoughts on Modules Yosemite Short Line Flat Car And much more… The O Scale Resource July/August 2014 1 Bill Of Lading 2 Table of contents Published Bi Monthly 3 Editorial comment 4 News and Reviews The Model Railroad Resource LLC 8 Sand Cast Models Plymouth, Wisconsin A look at how some of the O Scale models were made Editors 25 The Yosemite Short Line Glenn Guerra A sectional modular club layout [email protected] 37 Yosemite Short Line Flat Car Dan Dawdy Some information and drawings of the last remaining car [email protected] 44 The John Hammond Car Company A brief synopsis Copy Editor 45 Looking at Layout Automation Amy Dawdy Accessory (turnout) decoders 53 John Houlihan’s Layout July-August 2014 A look at John’s layout past and present Vol 1 #6 62 Locomotive Lighting Using MV lenses Welcome to the online O Scale Resource magazine. The magazine is presented in an easy 67 Some Thoughts on Modules to use format. The blue bar above the magazine A look at some different ideas on modules has commands for previewing all the pages, advancing the pages forwards or back, searching 76 O Scale Shows & Meets to go to a specific page, enlarging pages, printing pages, enlarging the view to full screen, and 77 The O Scale Resource Classifieds downloading a copy to your computer. Front Cover Photo A Souther Pacific local freight heads up into the Tehachapi mountains on John Houlihan’s layout Advertisers Index Alleghyeney Scale Models Pg 52 Korber Models Pg 52 Altoona Model Works Pg 66 P & D Hobby Shop Pg 66 Rear Cover Photo BTS Pg 24 Rich Yoder Models Pg 44 Clover House Pg 52 San Juan Car company Pg 66 Crow River Models Pg 44 SMR Trains Pg 52 Small town on the Yosemite Short Delta Models Pg 24 Stevenson Preservation Lines Pg 66 Line Railroad. -

Northern Ohio Railway Museum Used Book Web Sale

NORTHERN OHIO RAILWAY MUSEUM USED BOOK 6/9/2021 1 of 20 WEB SALE No Title Author Bind Price Sale 343 100 Years of Capital Traction King Jr., Leroy O. H $40.00 $20.00 346026 Miles To Jersey City Komelski, Peter L. S $15.00 $7.50 3234 30 Years Later The Shore Line Carlson, N. S $10.00 $5.00 192436 Miles of Trouble Morse, V.L S $15.00 $7.50 192536 Miles of Trouble revised edition Morse, V.L. S $15.00 $7.50 1256 3-Axle Streetcars vol. 1 From Robinson to Rathgeber Elsner, Henry S $20.00 $10.00 1257 3-Axle Streetcars vol. 2 From Robinson to Rathgeber Elsner, Henry S $20.00 $10.00 1636 50 Best of B&O Book 3 50 favorite photos of B&O 2nd ed Kelly, J.C. S $20.00 $10.00 1637 50 Best of B&O Book 5 50 favorite photos of B&O Lorenz, Bob S $20.00 $10.00 1703 50 Best of PRR Book 2 50 favorite photos of PRR Roberts, Jr., E. L. S $20.00 $10.00 2 Across New York by Trolley QPR 4 Kramer, Frederick A. S $10.00 $5.00 2311Air Brake (New York Air Brake)1901, The H $10.00 $5.00 1204 Albion Branch - Northwestern Pacific RR Borden, S. S $10.00 $5.00 633 All Aboard - The Golden Age of American Travel Yenne, Bill, ed. H $20.00 $10.00 3145 All Aboard - The Story of Joshua Lionel Cowan Hollander, Ron S $10.00 $5.00 1608 American Narrow Gauge Railroads (Z) Hilton, George W. -

Southern Pacific Company Records MS 10MS 10

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8154q33 No online items Guide to the the Southern Pacific Company Records MS 10MS 10 CSRM Library & Archives staff 2018 edition California State Railroad Museum Library & Archives 2018 Guide to the the Southern Pacific MS 10 1 Company Records MS 10MS 10 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: California State Railroad Museum Library & Archives Title: Southern Pacific Company records creator: Southern Pacific Company Identifier/Call Number: MS 10 Physical Description: 478.15 Linear Feet Date (inclusive): 1860-1989 Abstract: This collection includes some of the corporate records of the Southern Pacific Railroad, its holding company, the Southern Pacific Company and certain of its subsidiaries and successors (such as the Southern Pacific Transportation Company) collected by the CSRM Library & Archives, focusing on financial and operational aspects of its functions from 1860 to 1989. Language of Material: English Language of Material: English Statewide Museum Collections Center Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research by appointment. Contact Library staff for details. Accruals The CSRM Library & Archives continues to add materials to this collection on a regular basis. Immediate Source of Acquisition These corporate records were pieced together through donations from multiple sources. including: the Southern Pacific Transportation Company, the Union Pacific Railroad, The Bancroft Library; University of California, Berkeley, The Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, Pacific Coast Chapter, and people including: John Vios, Erik Pierson, Timothy and Sylvia Wong, Edna Hietala, John Gilmore, Philip Harrison, Carl Bradley, Betty Jo Sunshine, Dave Henry, Anthony Thompson, Lynn D. Farrar and many others between 1977 and 2009. Arrangement Arranged by department into the following series: Series 1: Motive Power Department records Subseries 1. -

C:\Users\Jacque\Documents\Jacque\SPCRR\HOTBOX\HOTBOX-MAR APR 2021\HOTBOX Mar Apr 2021 Ver 2.Pmd

17 March/April 2021 A newsletter from SPCRR and The Railroad Museum at Ardenwood The Hotbox newsletter provides historic information on Carter Bros. Builders of Newark, CA; the South Pacific Coast Railroad, and other regional narrow gauge railroads; as well as updates for our members, volunteers, and the general public about our special events, activities, and volunteer opportunities at The Railroad Museum at Ardenwood. The museum is operated by the Society for the Preservation of Carter Railroad Resources (SPCRR). If you have any questions or comments, you can reach a staff member by email at [email protected] or call 510-508-8826. The Museum’s mission is the preservation, restoration and interpretation of regional narrow gauge railroad history, including Carter Brothers—a pioneer railroad car builder in California. We are located at Ardenwood Historic Farm, 34600 Ardenwood Blvd, Fremont, CA. We are a 501(c)(3) nonprofit and all donations are tax deductible. Donations are greatly appreciated through our website or by mail (SPCRR, PO Box 783, Newark, CA 94560). Trains operate on Thursday, Friday, Sunday and holidays between April & mid-November. See our Calendar on the last page for our current schedule and special events. To make a donation, become a member, or for more information please go to our website www.spcrr.org. Newsletters are distributed six times a year. We also have more information on our events at www.facebook.com/spcrrmuseum. A Long Time Ago... BETTERAVIA, where we obtained the rail to begin our railroad Don Marenzi, General Manager and Curator Photos by the author unless otherwise noted ere are my memories of the Betteravia cattle feed lot railroad and SPCRR's part of Hthe rail story along with some other early SPCRR recollections. -

Train Day 2014 Saturday, May 10, 2014 Was Amtrak Sponsored National Train Day

News from the San Luis Obispo Railroad Museum Issue Number 50 San Luis Obispo, California, Summer 2014 www.slorrm.com Amtrak Surfliner trundles past the Museum’s speeders on its way south. Train Day 2014 Saturday, May 10, 2014 was Amtrak sponsored National Train Day. The San Luis Obispo Railroad Museum was open to the public. Docents were on hand to explain the many exhibits. The gift shop was open and speeder rides were Here is the latest arrival at the the car for catered lunches, dinners, available. More pictures on page 7 Museum. The LaCondesa was donated meetings, birthday parties and wine to the museum in 2006 by Gordon tastings. Crosthwait, a retired teacher who lived The Santa Fe did not name the car, in Los Osos and worked in the Morro only using its number 1512. Tad Finlay Bay and San Luis Obispo schools. It named it Margareta del Oro. Gordon was stored and used by the Santa Maria renamed it La Condesa. We hope to Valley Railroad until it was moved to have a contest and change the name to the display track in May, 2014. reflect the Central Coast. The car was built by the Pullman We are fortunate that the car has a Company in 1926 for the Santa Fe large lounge. We can use the car now Railroad as a diner/lounge observation but plan to convert it back to a diner Above: Visitors line the rail as the north- car. It was purchased from the Santa lounge. All the original fixtures are in bound Coast Starlight approaches. -

MISSIONS of CALIFORNIA by Maj. Ben C. Truman

I MISSIONS OF CALIFORNIA By Maj. Ben C. Truman THE PRESS OF PUBLISHED BY Geo. Rice & Sons, (Inc.) M. R i e d e r LOS ANGELES, CAL. 234 N ew High St. Los Angeles Copyright 1903 BY M. R I E D E R flinn inun nf <Ual ifnruia BY MAJ. BEN. C. TRUMAN ---HERE is a growing interest m the Missions of Califor- and heroic memories;. no historic race beginnings, as have other nia-those first outposts of permanent civilization on lands and older peoples, in whose realms the race was cradled. Tthe Pacific Coast between San Diego and San Fran The earlier past of this new world is largely enveloped in cisco-and all those churches that were not permitted darkness, but occasionally evidences are discovered which prove to go into decay after their secularization have under conclusively that a long line of pre-historic peoples must have gone more or less repairs, and are now in a good state of preser lived and vanished before the coming of the Europeans to our vation. The churches at San Luis Rey, San Juan Capistrano, 3hores. The mighty ruins discovered in Mexico and in Central San Gabriel, Santa Barbara, Ventura, San Luis Obispo, Monte America are the hieroglyphics of dead nations; old, almost, per rey, Santa Clara and San Francisco have received marked at haps, as those who were cradled in the Orient "in the begin tention from clubs and other bodies for the past two or three ning." But possibly some future Schliemann may yet uncover decades, and a number of these may be said to rank higher than these buried monuments to unwritten history and help us to any of the other landmarks that meet the eye of the traveler in read and study the lives of the vanished races that have gone Florida, Texas, Arizona, New Mexico and Canada. -

NASG S Scale Magazine Index PDF Report

NASG S Scale Magazine Index PDF Report Bldg Article Title Author(s) Scale Page Mgazine Vol Iss Month Yea Dwg Plans "1935 Ridgeway B6" - A Fantasy Crawler in 1:24 Scale Bill Borgen 80 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 2004 "50th Anniversary of S" - 1987 NASG Convention Observations Bob Jackson S 6 Dispatch Dec 1987 "Almost Painless" Cedar Shingles Charles Goodrich 72 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 1994 "Baby Gauge" in the West - An Album of 20-Inch Railroads Mallory Hope Ferrell 47 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Jul - Aug 1998 "Bashing" a Bachmann On30 Gondola into a Quincy & Torch Lake Rock Car Gary Bothe On30 67 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Jul - Aug 2014 "Been There - Done That" (The Personal Journey of Building a Model Railroad) Lex A. Parker On3 26 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 1996 "Boomer" CRS Trust "E" (D&RG) Narrow Gauge Stock Car #5323 -Drawings Robert Stears 50 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz May - Jun 2019 "Brakeman Bill" used AF trains on show C. C. Hutchinson S 35 S Gaugian Sep - Oct 1987 "Cast-Based" Rock Work Phil Hodges 34 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Nov - Dec 1991 "Causey's Coach" Mallory Hope Ferrell 53 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Sep - Oct 2013 "Chama," The PBL Display Layout Bill Peter, Dick Karnes S 26 3/16 'S'cale Railroading 2 1 Oct 1990 "Channel Lock" Bench Work Ty G. Treterlaar 59 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 2001 "Clinic in a Bag" S 24 S Gaugian Jan - Feb 1996 "Creating" D&RGW C-19 #341 in On3 - Some Tips Glenn Farley On3 20 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Jan - Feb 2010 "Dirting-In" -

Model Railroads of Southern California & the Central Coast

Model Railroads of Southern California & The Central Coast Railroad Festival Layout Tour No. 50 October 6 - 9, 2016 (Thur. - Sun.) http://ccrrf.com/ http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Model_Railroads_Of_Southern_California/ Copyright 2016 Model Railroads of Southern California Updated 9/19/16 Owner / Dates & Railroad Major Cross Scale Address Phone Group Times Open Name Streets Thursday & Friday Model Central 10:00 - 6:00 Train 7600 El Camino Real, HO, N, El Camino Real & Coast Saturday Store Suite 3, 805-466-1391 O & G Pueblo Avenue Trains 10:00 - 5:00 Display Atascadero Sunday By Layouts Appointment Geoff Sunday Garden G Clinton 10:00 - 3:00 Railroad Doc Thursday Village Burnstein's through 114 W. Branch Street, Grand Ave. & U.S. Overhead G 805-474-4068 Ice Cream Sunday Arroyo Grande Highway 101 Railroad Lab 12:00 - 9:00 Doc Thursday Village Burnstein's through 168 W. Clark Avenue, Broadway Street & Overhead G 805-614-7644 Ice Cream Sunday Orcutt Clark Avenue Railroad Lab 1:00 - 9:00 Mark Saturday Unnamed G Edwards 10:00 - 3:00 DK & George Friday Pacific HO & This layout open only to members of Model Railroads of Gibson 11:00 - 4:00 Mountain HOn3 Southern California and their guests. Railway Anthony Saturday Unnamed N Harris 10:00 - 4:00 Lompoc Valley Saturday & Valley 428 North “I” Street, Laurel Avenue & Model RR & Sunday Coast HO 805-757-0249 Lompoc “H” St. (Highway 1) Historical 10:00 - 4:00 Lines Society Friday 7:00 - 10:00 Andrew SP Coast Sunday HO Merriam Line 10:00 - 2:00 Sunday Garden Ed Morse G 10:00 - 3:00 Railroad Obermeye Bill Sunday r Ranch HO Obermeyer 9:00 - 6:00 Railroad Saturday Museum Oceano 10:00 - 7:00 1650 Front Street Belridge & 805-489-5446 Display HO Depot Assn. -

Railroads of Los Gatos by Edward Kelley, 979.473 H64

Railroads of Los Gatos by Edward Kelley, 979.473 H64 Aahmes Temple Shrine 61 Adams, David 75 ALCO Brooks Works 52 Alma 12,27 Alexander, Myron 69,75 American Car Company 23 Amtrack's Coast Starlight 7 Antelope and Western Railroad 84 Anti-Chinese sentiments 8 Arizona Eastern Railway 86,96 “Ashcan” headlight 97 Austin Corners 24 Automatic braking systems 65 Baggerly, John 30 Baldwin Locomotive Works 7,14 Bamburg, Marvin 105 Bank of America 4 Barlow, George 117 Beattie, Dorothy 112 Bell at Vasona Junction 66 Big Trees and Pacific Railroad 126 “Billy Cat” 74,114 Billy Jones Wildcat Railroad 105, 108,111 “Black Widow” paint scheme 120 Blowdown 44 Boulder Creek 8 Broad gauge trains 8-9,16,19 Broggie, Roger 55 Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers 51 Caboose 63,82,106 Calistoga Steam Railway 108 Camino, Cable and Northern 84 Canadian Pacific Railway 76 Carolwood Pacific railroad 56 Carrick, John 83 Carter Brothers of Newark 17 Casper Lumber Company Mallet 83 Cats' Canyon 8,12,20,34 Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia 1876 7 Centennial, Billy Jones Wildcat Railroad 119 Central Coast Railway Club 92,98,101 Charitable donations via Wildccd Railroad 64 Chess, T. Louis 30,99,100 Children’s Holiday Parade 112,118 Chinese laborers 8,12 Clark, F. Norman 73 Cleveland, L.H. 101 Coast Daylight, Southern Pacific Company 41,44 Coit, John 46-47,113 Colgrove, George 14 Comstock Lode 8 Congress Junction 9 Cooney, Russell 75 Courtside Club 124 Crider’s Department Store 88 Crossing gates and crossing signals 18 “Crummy” 63 Cuesta Grade 43,44 Custom Locomotive Works of Chicago 120,121 “Dancing Man” 56 Daves Avenue prune orchard 2 Davis, Alfred “Hog” 7 Deadheading 39,40 Denver and Rio Grande Railroad 7 De Paolo, Betty 75 Derailments 37 “Desert Chime” 83 Dieselization 97 Diridon, Rod 125 Disney, Walt 55-57 Disneyland 56,57 Donner Pass fire train 100 Dual gauge track 17 Earthquake, 1906 8,19 Eastlake Park Railway No. -

City Profile

CITY PROFILE DEMOGRAPHICS, STATISTICS, AND HISTORICAL INFORMATION More than 150,000 people a year attend the Santa Downtown Fridays draw more than 1,500 people each Barbara County Fair held in Santa Maria. The popular week for entertainment and food. The event is a Strawberry Festival also is hosted at the Santa Maria partnership among the City and local organizers, to Valley Fairpark. stimulate the community’s downtown core. The Santa Maria Valley is rich in agriculture and home Tens of thousands of travelers per day along Highway 101 to some of the ripest, juiciest, largest strawberries in are welcomed into town by this sign. Santa Maria has long the country. Farmers grow multiple varieties and been a regional shopping center and continues to attract harvest more than 7,500 acres annually. more companies due to its business-friendly approach. Homebuyers appreciate Santa Maria’s affordability Before Sunset Magazine named our valley’s classic feast on California’s Central Coast. More than 1,000 the “best barbecue in the world”, the California Visitor’s housing units are either under construction or in plan Guide dubbed our famous Santa Maria Style Barbecue review as of mid-2020. “the number one food not to miss while visiting California.” xvii CITY PROFILE DEMOGRAPHICS, STATISTICS, AND HISTORICAL INFORMATION The City of Santa Maria is located in Santa Barbara Composition of Population: County on the west coast of California in what is Age Analysis: City: State: known as the Central Coast. Santa Maria is the Male 50.33% 49.7% largest city by population and geographic area in the Female 49.67% 50.3% County (23.2 square miles).