9781908984807 Extract.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Passion for Valpolicella Since 1843

A passion for Valpolicella since 1843 Beyond tradition: relaunch guidelines. A passion for Valpolicella since 1843. 1.0 The value of tradition The winery’s history The Santi winery has been a leading producer in the Valpolicella area since 1843, the year it was established in Illasi, in the hills of the valley once called Longazeria. Carlo Santi was the first, followed by his successors Attilio Gino and Guido, to embark on a path that pursued excellence. Nowadays Cristian Ridolfi, Santi’s winemaker, embraces and continues this path, transforming the winery into a point of reference for the Valpolicella area in several Countries. A passion for Valpolicella since 1843. A passion for Valpolicella since 1843. 2 2.0 The land at the origins of our culture A knowledge of the terroir Santi’s wine maker constantly co-operate with the agronomic team to select the best rows in each valley of the Valpolicella area, considering the following features: soil, altitude, exposure and plant training system. This agronomic model allows Santi to create wines with a unique style, expression of the terroir variety among the several valleys that composes it. A passion for Valpolicella since 1843. 3 2.0 The land at the origins of our culture Santi’s selections in Valpolicella 1, FUMANE VALLEY Full bodied and dry wines 1 2 2, MARANO VALLEY Elegant wines of high aromatic intensity 3 4 5 3, NEGRAR VALLEY Tasty and long lived wines 4. VALPANTENA VALLEY Wines with spicy and mineral notes 5. ILLASI VALLEY Fragrant and very smooth wines with intense colour, NEW AREA OF VENTALE AREA OF PROEMIO AREA OF SOLANE VINEYARDS VINEYARDS VINEYARDS & AMARONE VINEYARDS A passion for Valpolicella since 1843. -

Massimago “Duchessa Allegra” Garganega IGT

Artisanal Cellars artisanalcellars.com [email protected] Massimago “Duchessa Allegra” Garganega IGT Winery: Massimago Category: Wine – Still – White Grape Variety: Garganega Region: Mezzane di Sotto / Veneto / Italy Vineyard: Estate Winery established: 2003 Feature: Organic Product Information Soil: Layers of limestone, marl and clay Elevation: 80 – 100 meters (262 to 330 feet) Vinification: 20% of the grapes are harvested before the main harvest to make sure to have a deep freshness in the wine. The rest is picked at perfect ripeness. Skin maceration takes place for a few days. After vinification, malolactic fermentation takes place in steel vats for 5 months. Planting Density: 3,000 vines/ha. Tasting Note: Yellowish straw color with pale green reflections. Tangy citrus aroma reminiscent of grapefruit and green apples. On the palate, crunchy clean, with fruity notes and high minerality which combine harmoniously to achieve perfect balance. “I wanted to give my Garganega the opportunity to express herself in a different way. I wanted her to finally become a real lady; she introduces herself with a citrus bouquet almost grapefruit like. The slow gentle drying of her grapes has concentrated 50 years of history into glorious essence drops. The perfect combination should be… in front of the fireplace with a fish soup.” Production: 5,000 – 8,000 bottles/ year Alc: 12.5% Producer Information Located in the Val di Mezzane valley (Eastern Valpolicella) over a hill surrounded by woods, this gorgeous estate is managed with creativity and strong determination by Camilla Rossi Chauvenet and her coworkers. The name of the winery is from the Latin "Maximum Agium", maximum benefit. -

Wine by the Glass Bin # White Glass Bottle

WINE BY THE GLASS BIN # WHITE GLASS BOTTLE 117 Prosecco - Barocco - Veneto, Italy….................................................................................. 10 38 118 Brut Rose - J. Laurens Cremant de Limoux - Languedoc, France…......................................12 46 116 Moscato d'Asti - G.D. Vajra - Piedmont, Italy…..................................................................................................................12 46 106 Riesling - Gunderloch Kabinett - Rheinhessen, Germany…............................................................12 46 110 Pinot Grigio - Le Pianure - Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, Italy…...........................................................................................................................................9 34 105 Sauvignon Blanc - Mohua - Marlborough, New Zealand…..................................................................................................10 104 Sauvignon Blanc - Domaine Fernand Girard - Sancerre, France….............................................................................................18 70 111 Nascetta - Fabio Oberto - Piedmont, Italy….........................................................................12 46 112 Garganega-Chardonnay - Scaia - Veneto, Italy…..........................................................................9 34 113 Chardonnay - Matchbook - Dunnigan Hills, CA…...................................................................................................................10 108 Chardonnay - Alois Lagedar - Trentino Alto-Adige, -

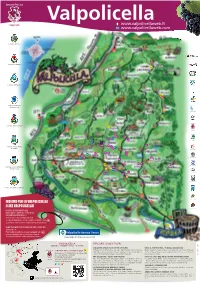

MAPPA-VALPO-2019.Pdf

Consorzio Pro Loco Valpolicella Valpolicella www.valpolicellaweb.it www.valpolicellaweb.com Comune di Dolcè Comune di Negrar 52 53 Comune di Fumane 49 39 Comune di Marano di Valpolicella 38 41 Consorzio Pro Loco Comune di Pescantina 51 Valpolicella 12 30 26 19 48 1 Pro Loco Molina 42 9 Comune di San Pietro 14 15 5 37 40 47 in Cariano 4 27 Pro Loco Volargne 7 11 13 16 35 44 17 23 46 18 10 Pro Loco Sant’Anna d’Alfaedo 29 36 54 20 21 8 31 Pro Loco Gargagnago Comune di Sant’Ambrogio 22 di Valpolicella 33 34 45 25 2 Pro Loco Breonio 3 43 24 32 6 Pro Loco San Giorgio 28 Comune di Sant’Anna d’Alfaedo Pro Loco Ospetaletto INSIEME PER LA VALPOLICELLA! 41 I LIKE VALPOLICELLA! Pro Loco Pescantina MOSTRA QUESTA MAPPA AGLI INSERZIONISTI ADERENTI E RICEVERAI UN BUONO SCONTO DEL 5% Trova l’elenco delle strutture aderenti 41 su valpolicellaweb.it o sul retro quelle con bollino rosso La promozione è valida secondo le condizioni applicate da ogni aderente. 50 SHOW THIS MAP TO PARTNERS AND GET A DISCOUNT TICKET OF 5% Find the list of partners on valpolicellaweb.com or those identi ed with a red dot on the back The promotion is valid under conditions applied by each member. www.valpolicellabenacobanca.it VALPOLICELLA PERCORSI / DAILY TOURS VERONA - VENETO - ITALY - EUROPE ANDAR PER CHIESE / TOUR OF THE CHURCHES VERSO IL PONTE DI VEJA / TOWARDS VEJA BRIDGE Consorzio Pro Loco CONSORZIO PRO LOCO VALPOLICELLA 54 Fumane (Grotta di Fumane – Santuario della Madonna de Le Salette – Negrar (Giardino Pojega, Chiesa di San Martino), Sant’Anna d’Alfaedo Villa della Torre), San Floriano (Pieve), Valgatara (Chiesa di San Marco), (Ponte di Veja – Museo Paleontologico e Preistorico), Fosse (Chiesa di Via Ingelheim, 7 - 37029 S. -

Linee E Orari Bus Extraurbani - Provincia Di Verona

Linee e orari bus extraurbani - Provincia di Verona Servizio invernale 2019/20 [email protected] 115 Verona - Romagnano - Cerro - Roverè - Velo ................................... 52 Linee da/per Verona 117 S.Francesco - Velo - Roverè - S.Rocco - Verona .............................. 53 101 S. Lucia - Pescantina - Verona ........................................................14 117 Verona - S.Rocco - Roverè - Velo - S.Francesco .............................. 53 101 Verona - Pescantina - S. Lucia ........................................................15 119 Magrano - Moruri - Castagnè - Verona .............................................54 102 Pescantina - Bussolengo - Verona .................................................. 16 119 Verona - Castagnè - Moruri - Magrano .............................................54 102 Verona - Bussolengo - Pescantina .................................................. 16 120 Pian di Castagnè/San Briccio - Ferrazze - Verona ............................ 55 90 Pescantina - Basson - Croce Bianca - Stazione P.N. - p.zza Bra - P. 120 Verona - Ferrazze - San Briccio/Pian di Castagnè ............................ 55 Vescovo ............................................................................................... 17 121 Giazza - Badia Calavena - Tregnago - Strà - Verona ......................... 56 90 P.Vescovo - p.zza Bra - Stazione P.N. - Croce Bianca - Basson - 121 Verona - Strà - Tregnago - Badia Calavena - Giazza ......................... 58 Pescantina ............................................................................................17 -

Publication of a Communication of Approval of a Standard Amendment to a Product Specification for a Name in the Wine Sector Refe

5.3.2020 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union C 72/33 Publication of a communication of approval of a standard amendment to a product specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 17(2) and (3) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 (2020/C 72/14) This communication is published in accordance with Article 17(5) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 (1). COMMUNICATING THE APPROVAL OF A STANDARD AMENDMENT ‘SOAVE’ Reference number: PDO-IT-A0472-AM05 Date of communication: 2 December 2019 DESCRIPTION OF AND REASONS FOR THE APPROVED AMENDMENT 1. Formal amendment For the ‘Classico’ type, the term ‘subarea’ has been replaced by the term ‘specification’. This is a formal amendment to take account of the exact wording provided in Italian law. This formal amendment concerns Article 1 of the Product Specification but it does not affect the Single Document. 2. Vine training systems The vine training systems have been extended to include GDC and all forms of trellises. The reason for this amendment is to adapt the Product Specification to the development of more modern and innovative vine training systems (particularly the various new kinds of trellises) and the need for agronomic methods to take account of climate change. This formal amendment concerns Article 4 of the Product Specification but it does not affect the Single Document. 3. Vine density per hectare As regards vine density per hectare (at least 3 300), the reference to the Decree of 7 May 1998 has been deleted. This is a formal amendment given that newly planted vines must have a minimum density of 3 300 plants per hectare. -

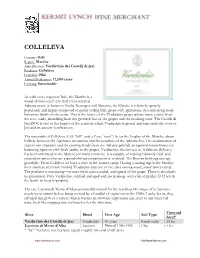

Colleleva.Pdf

COLLELEVA Country: Italy Region: Marche Appellation(s): Verdicchio dei Castelli di Jesi Producer: Colleleva Founded: 1984 Annual Production: 12,500 cases Farming: Sustainable As with every region in Italy, the Marche is a world all unto itself. On Italy’s less traveled Adriatic coast, in between Emilia-Romagna and Abruzzo, the Marche is relatively sparsely populated, and largely composed of gently rolling hills, green with agriculture, that end along steep limestone bluffs on the coast. This is the home of the Verdicchio grape, whose name comes from the root verde, describing both the greenish hue of the grapes and the resulting wine. The Castelli di Jesi DOC is one of the largest of the zones in which Verdicchio is grown and surrounds the town of Jesi and its ancient fortifications. The vineyards of Colleleva (Colle “hill”, and si Leva, “rises”) lie on the heights of the Marche: about halfway between the Apennine mountains and the coastline of the Adriatic Sea. The combination of eastern sun exposure and the cooling winds from the Adriatic provide an optimal microclimate for balancing ripeness with fresh acidity in the grapes. Verdicchio, also known as Trebbiano di Soave, has been cultivated in the Marche for many centuries. It is capable of making vibrantly fresh and crisp white wines that are a wonderful accompaniment to seafood. The Riserva bottlings can age gracefully. From Colleleva we have a wine in the former camp. During a tasting trip in the Marche, their stainless steel tank vinified Verdicchio was one of the stars among many, many wines tasted. The perfume is entrancing—at once fresh and rounded, and typical of the grape. -

Scarica Il Documento

CAPOFILA N. DISTRETTO COM CAPOFILA COM COMUNI DISTRETTO COMUNI Affi Brentino Belluno Brenzone Caprino Veronese Cavaion Veronese VR 1 Comunità Montana 18 Caprino V.se del Baldo del Baldo Costermano Ferrara di Monte Baldo Malcesine Rivoli Veronese S. Zeno di Montagna Torri del Benaco 11 Dolcè Fumane Sant’Ambrogio Marano di Valpolicella 15 VP VR 2 Negrar della Sant'Ambrogio S. Ambrogio di Valpolicella Lessinia Valpolicella S. Anna d’Alfaedo Occidentale Bussolengo Pastrengo 17 Pescantina Pescantina S. Pietro in Cariano 10 Bosco Chiesanuova Cerro Veronese Erbezzo Bosco 2 Chiesanuova Grezzana Rovere Veronese S. Mauro di Saline Velo Veronese VR 3 Badia Calavena della Comunità Montana Lessinia della Lessinia Cazzano di Tramigna Orientale Illasi Mezzane di sotto Montecchia di Crosara 3 Illasi Roncà S. Giovanni Ilarione Selva di Progno Tregnago Vestenanova 17 CAPOFILA N. DISTRETTO COM CAPOFILA COM COMUNI DISTRETTO COMUNI Belfiore Monteforte D’Alpone 4 San Bonifacio S. Bonifacio Soave Albaredo d’Adige Arcole Bevilacqua Bonavigo Boschi S.Anna VR 4 Cologna Veneta del Cologna Veneta 7 Cologna V.ta Colognese Minerbe Pressana Roveredo di Guà Terrazzo Veronella Zimella Caldiero Colognola ai Colli 8 San Martino BA Lavagno S. Martino Buon Albergo 20 San Giovanni Lupatoto 5 Zevio Zevio Angari Bovolone Isola Rizza Oppiano 6 Bovolone Palù Ronco all’Adige VR 5 Legnago delle Valli Roverchiara S. Pietro di Morubio Casaleone Cerea 9 Cerea Concamarise Sanguinetto Castagnaro 11 Legnago Legnago Villa Bartolomea 17 CAPOFILA N. DISTRETTO COM CAPOFILA COM COMUNI DISTRETTO COMUNI Buttapietra Gazzo Veronese Isola della Scala 10 Isola D/S Nogara Salizzole VR 6 Sorgà Isola della Scala Isolano Castel d’Azzano Erbè Mozzecane 12 Mozzecane Nogarole Rocca Trevenzuolo Vigasio 12 Povegliano veronese Sommacampagna 13 Villafranca Valeggio sul Mincio Villafranca Veronese VR 7 Villafranca Castelnuovo del Garda Zona Mincio Veronese 14 Peschiera D/G Peschiera del Garda Sona Bardolino 16 Bardolino Garda Lazise. -

Guerrieri Rizzardi 2016 Soave Dop Classico

GUERRIERI RIZZARDI 2016 SOAVE DOP CLASSICO PRODUCER INFO Guerrieri-Rizzardi, the historic house in Veneto, dates back to the unification of two ancient estates in 1913, when Carlo Rizzardi from Valpolicella, married Guiseppina Guerrieri of Bardolino. The new winery is completely solar powered, combining the best that technology offers in a carbon neutral way with vineyards that have been in the family for centuries. With the energy of the new younger generation in the family, Guerrieri-Rizzardi has experienced a renaissance of sorts over the last twenty years and is known throughout Europe as one of the finest, most classical producers in the region, with wines built on tension and "cut." ABOUT THE WINE “Classico” designated Soave is a relatively rare thing to find nowadays, representing only 15% of the Soave region’s production – “Classico” designated wines are sourced from the (far superior) original hillside plots that were the zone’s standard prior to the massive/controversial expansion of the DOC in the 1970’s. Grapes are sourced from two “cru” vineyards – Costeggiola (limestone soil) and Rocca (volcanic soil). The Garanega here is picked when extremely ripe, the Chardonnay is picked early to provide acidic balance, the ancient vine Trebbiano d’Soave lends some heirloom charm. Fermented/aged in cement, lees aging provides extra texture. While some of Rizzardi’s peers in the top echelon of Soave Classico focus on aromatics, Rizzardi’s Soave has always been about palate detail and mineral character. Vintage: 2016 | Wine Type: White Wine Varietal: 75% Garganega, 20% Chardonnay and 5% Trebbiano di Soave Origin: Italy | Appellation: Soave Classico DOP Elaboration: All grapes destemmed then follow alcoholic fermentation in cement vats for 10 days at between 15 to 16°C. -

Vicenza, Italia Settentrionale) (Decapoda, Stomatopoda, Isopoda)

CCITTÀITTÀ DDII MMONTECCHIOONTECCHIO MAGGIOREMAGGIORE MMUSEOUSEO DDII AARCHEOLOGIARCHEOLOGIA E SCIENZESCIENZE NNATURALIATURALI ““G.G. ZZANNATO”ANNATO” CLLAUDIOAUDIO BEESCHINSCHIN, ANNTONIOTONIO DE ANNGELIGELI, ANNDREADREA CHHECCHIECCHI, GIIANNINOANNINO ZAARANTONELLORANTONELLO CCROSTACEIROSTACEI DELDEL GGIACIMENTOIACIMENTO EEOCENICOOCENICO DDII GGROLAROLA PPRESSORESSO SSPAGNAGOPAGNAGO DDII CORNEDOCORNEDO VICENTINOVICENTINO ((VICENZA,VICENZA, ITALIAITALIA SETTENTRIONALE)SETTENTRIONALE) ((DECAPODA,DECAPODA, STOMATOPODA,STOMATOPODA, ISOPODA)ISOPODA) MONTECCHIO MAGGIORE (VICENZA) 2012 Iniziativa realizzata con il contributo della Regione del Veneto Museo di Archeologia e Scienze Naturali “G. Zannato” Sistema Museale Agno-Chiampo Città di Montecchio Maggiore Associazione Amici del Museo Zannato Montecchio Maggiore Copyright © Museo di Archeologia e Scienze Naturali “G. Zannato” Piazza Marconi, 15 36075 Montecchio Maggiore (Vicenza) Tel.-Fax 0444 492565 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-88-900625-2-0 Casa editrice Cooperativa Tipografica Operai - Vicenza Le riproduzioni dei beni di proprietà dello Stato Italiano sono state realizzate su concessione del Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali; è vietata l’ulteriore riproduzione e duplicazione con qualsiasi mezzo. In copertina: disegni di A. De Angeli ©. Claudio BesChin, antonio de angeli, andrea CheCChi, giannino Zarantonello CROSTACEI DEL GIACIMENTO EOCENICO DI GROLA PRESSO SPAGNAGO DI CORNEDO VICENTINO (VICENZA, ITALIA SETTENTRIONALE) (DECAPODA, STOMATOPODA, ISOPODA) -

Bardolino Veneto

Bardolino Veneto Appellation: BARDOLINO DOC Zone: Custoza (Sommacampagna, province of Verona) Cru: n/a Vineyard extension (hectares): 7 Blend: 60% Corvina - 30% Rondinella - 10% Molinara Vineyard age (year of planting): Corvina 1911, 2013 - Molinara 1911,2013 - Rondinella 1911,2013 Soil Type: morainic Exposure: South Altitude: 150 meters above sea level Colour: bright ruby red Nose: Fruity with cherry and hard black cherry notes Serving temperature (°C): 16-18 Match with: Average no. bottles/year: 65,000 Grape yield per hectare tons: n/a Notes: The yield is approx. 60 hectolitres of wine/hec- tare. Destemming and crushing of the clusters, fermentation for 72 hours at 28 degrees Celsius, the temperature is then lowered to 25 degrees Celsius for 24 hours. The wine is racked off and the alcoholic fermentation is completed after 8/10 days at 20 degrees Celsius. Malolactic fermentation. The wine Awards: n/a Estate History Azienda Agricola Cavalchina is located in Custoza, a district of Sommacampagna, province of Verona The estate was established at Fernanda, Trebbiano and Garganega grapes) “Custoza” and to sell it in Rome and in Milan, the most important markets of the time. Only the grape varietals that are most suited for the area are grown, yields are kept low and only the best clusters go into the wine that is bottled. Modern techno- logy is used in the cellar, but tradition is also respected. The wines produced are: Bianco di Custoza DOC, Bardolino DOC, Bardolino Chiaretto, Bardolino Superiore DOCG. MARC DE GRAZIA SELECTIONS SRL www.marcdegrazia.com FINE WINES FROM THE GREAT CRUS OF ITALY. -

Sant'ambrogio Di Valpolicella Verona - IT Tel +39 045 6832611 Fax +39 045 6860592 [email protected]

SANT’AMBROGIO DI VALPOLICELLA The Gateway to Valpolicella INDEX Sant’Ambrogio di Valpolicella THE GATEWAY TO VALPOLICELLA p. 2 La Valpolicella THE ORIGINS p. 4 Sant’Ambrogio di Valpolicella THE HAMLET OF THE FOUNTAIN I p. 6 San Giorgio di Valpolicella ONE OF “ITALY’S MOST BEAUTIFUL HAMLETS” II p. 12 Gargagnago THE HAMLET OF THE AMARONE III p. 16 Ponton THE HAMLET BY THE RIVER ADIGE IV p. 20 Monte THE HAMLET OF THE FORTRESS V p. 24 Domegliara THE HAMLET OF THE STATION VI p. 28 Sant’Ambrogio di Valpolicella THE GATEWAY TO VALPOLICELLA Thanks to its position on the crossing of some major transport routes, the town of Sant’Ambrogio can be considered “the natural gateway to Valpolicella”, as well as being host to one of Italy’s finest vineyards. The town of Sant’Ambrogio di Valpolicella is located 20 km from Verona and can be reached by car, train, bus and bicycle. Lake Garda is just 12 km away, and the highway and the railway connect it with Northern Italy and Northern Europe, through the beautiful Valdadige. The region of Sant’Ambrogio di Valpolicella, including the main town and its five hamlets, distinguishes itself for its typical historical villages. The area has varied features: smooth hills with vineyards, sharp rocks hanging on the valley, massive quarries from which the world-famous stones are extracted, the 1.112 meters high Mount Pastello, marking the northern border of the area, the river Adige, running slowly but at times fierily. Valpolicella overview A unique region, that offers a wide choice of history, culture and tradition, typical products, villas, ancient churches, Austrian fortresses and walls, trails in the nature, gourmet foods, renown wineries and different hosting solutions: little hotels, bed and breakfasts, charming relais.