Family-Based Territoriality Vs Flocking in Wintering Common Cranes Grus Grus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization of Gizzards and Grits of Wild Cranes Found Dead at Izumi Plain in Japan

FULL PAPER Wildlife Science Characterization of gizzards and grits of wild cranes found dead at Izumi Plain in Japan Mima UEGOMORI1), Yuko HARAGUCHI2), Takeshi OBI3) and Kozo TAKASE3)* 1)Laboratory of Veterinary Microbiology, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Agriculture, Kagoshima University, 1-21-24 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan 2)Izumi City Crane Museum, Crane Park Izumi, Izumi, Kagoshima 899-0208, Japan 3)Department of Veterinary Medicine, Joint Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kagoshima University, 1-21-24 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan ABSTRACT. We analyzed the gizzards, and grits retained in the gizzards of 41 cranes that migrated to the Izumi Plain during the winter of 2015/2016 and died there, either due to accident or disease. These included 31 Hooded Cranes (Grus monacha) and 10 White-naped Cranes (G. vipio). We determined body weight, gizzard weight, total grit weight and number per gizzard, and size, shape, and surface roundness of the grits. Average gizzard weights were 92.4 g for Hooded Cranes and 97.1 g for White-naped Cranes, and gizzard weight positively correlated with J. Vet. Med. Sci. body weight in both species. Average total grit weights per gizzard were 19.7 g in Hooded Cranes 80(4): 642–647, 2018 and 25.7 g in White-naped Cranes, and were significantly higher in the latter. Average percentages of body weight to grit weight were 0.8% in Hooded Cranes and 0.5% in White-naped Cranes. doi: 10.1292/jvms.17-0407 Average grit number per gizzard was 693.5 in Hooded Cranes and 924.2 in White-naped Cranes, and were significantly higher in the latter. -

Hooded Crane

Hooded Crane VERTEBRATA Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Panthera Category: 1 – critically endangered species at the territory of Russia The hooded crane (Grus monacha) is a small, dark crane, categorized as ‘vulnerable’ by IUCN. Distribution and Population: Distribution of Hooded Crane The estimated population of the species is approximately 9,200. The breeding grounds of this species are in south- eastern Siberia, Russian Federation, and northern China. More than 80 per cent of hooded cranes spend the winter at Izumi Feeding Station on the Japanese island of Kyushu. Small numbers are found at Yashiro in southern Japan (8,000 for wintering), in the Republic of Korea (100 for wintering) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (100 for wintering), and at several sites along the middle Yangtze River in China (1,000 for Source: BirdLife International Species Factsheet (2013): Crus breeding and wintering). Monacha Hooded cranes nest and feed in isolated sphagnum bogs scattered through the taiga in the southeastern Russian Federation, and in China, in forested wetlands in mountain valleys. Non- breeding birds are found in shallow open wetlands, natural grasslands, and agricultural fields in southern Siberia and north-eastern Mongolia. During migration, hooded cranes often associate with Eurasian and white-naped cranes. Physical features and habitats: Adult crowns are un-feathered, red, and covered with black hair-like bristles. The head and neck are snow white, which extends down the neck. The body plumage is otherwise slaty gray. The primaries, secondaries, tail, and tail coverts are black. Juvenile crown are covered with black and white feathers during the first year, and exhibit some brownish or grayish wash on their body feathers. -

Hooded Crane Nabe-Zuru (Jpn) Grus Monacha

Bird Research News Vol.4 No.1 2007.1.12. Hooded Crane Nabe-zuru (Jpn) Grus monacha Morphology and classification Life history Classification: Gruiformes Gruidae 123456789101112 wintering Total length: About 100cm Wing length: 480-530mm period migration breeding migration Tail length: 160-190mm Culmen length: 93-107mm Tarsus length: 200-230mm Breeding system: Weight: ♂ 3280-4870g ♀ 3400-3740g Hooded Cranes are monogamous. It is assumed that once they have paired, they usually maintain the pair-bond. When a partner Total length after del Hoyo (1996) and the others after Kiyosu (1978). died, however, the bereaved one sometimes mates with another bird again. Appearance: Male and female are simi- Age of the first breeding: lar in plumage coloration. Males and females are sexually mature at the age of about three They have an area of bare and five years, respectively, but unpaired females do not lay eggs, skin on the forehead. The even if they are mature (Ellis et al. 1996). skin exposed above the eye is red, but the other is Nest: black. They are charcoal There is no detailed information about the nest, but the size is as- gray all over except for sumed to vary greatly from one bird to another. There seems to be the area from the head to a nest with a diameter of several meters and a height of one meter. the nape, which is white. The study of Fujimaki et al. (1989) showed that they built a nest at They have tan bills and a height of 15-20cm above the water. The diameter of a nest was black legs. -

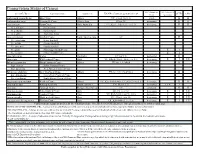

Conservation Status of Cranes

Conservation Status of Cranes IUCN Population ESA Endangered Scientific Name Common name Continent IUCN Red List Category & Criteria* CITES CMS Trend Species Act Anthropoides paradiseus Blue Crane Africa VU A2acde (ver 3.1) stable II II Anthropoides virgo Demoiselle Crane Africa, Asia LC(ver 3.1) increasing II II Grus antigone Sarus Crane Asia, Australia VU A2cde+3cde+4cde (ver 3.1) decreasing II II G. a. antigone Indian Sarus G. a. sharpii Eastern Sarus G. a. gillae Australian Sarus Grus canadensis Sandhill Crane North America, Asia LC II G. c. canadensis Lesser Sandhill G. c. tabida Greater Sandhill G. c. pratensis Florida Sandhill G. c. pulla Mississippi Sandhill Crane E I G. c. nesiotes Cuban Sandhill Crane E I Grus rubicunda Brolga Australia LC (ver 3.1) decreasing II Grus vipio White-naped Crane Asia VU A2bcde+3bcde+4bcde (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Balearica pavonina Black Crowned Crane Africa VU (ver 3.1) A4bcd decreasing II B. p. ceciliae Sudan Crowned Crane B. p. pavonina West African Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum Grey Crowned Crane Africa EN (ver. 3.1) A2acd+4acd decreasing II B. r. gibbericeps East African Crowned Crane B. r. regulorum South African Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled Crane Africa VU A2acde+3cde+4acde; C1+2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing II II Grus americana Whooping Crane North America EN, D (ver 3.1) increasing E, EX I Grus grus Eurasian Crane Europe/Asia/Africa LC unknown II II Grus japonensis Red-crowned Crane Asia EN, C1 (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Grus monacha Hooded Crane Asia VU B2ab(I,ii,iii,iv,v); C1+2a(ii) decreasing E I I,II Grus nigricollis Black-necked Crane Asia VU C2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Leucogeranus leucogeranus Siberian Crane Asia CR A3bcd+4bcd (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Conservation status of species in the wild based on: The 2015 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, www.redlist.org CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) - A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future. -

Testing the Utility of Mitochondrial Cytochrome Oxidase Subunit 1 Sequences for Phylogenetic Estimates of Relationships Between Crane (Grus) Species

Testing the utility of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 sequences for phylogenetic estimates of relationships between crane (Grus) species D.B. Yu*, R. Chen*, H.A. Kaleri, B.C. Jiang, H.X. Xu and W.-X. Du Department of Animal Science and Technology, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China *These authors contributed equally to this study. Corresponding author: W.-X. Du E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 10 (4): 4048-4062 (2011) Received November 1, 2011 Accepted December 19, 2011 Published December 21, 2011 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/2011.December.21.7 ABSTRACT. Morphology and biogeography are widely used in animal taxonomy. Recent study has suggested that a DNA-based identification system, using a 648-bp portion of the mitochondrial gene cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (CO1), also known as the barcoding gene, can aid in the resolution of inferences concerning phylogenetic relationships and for identification of species. However, the effectiveness of DNA barcoding for identifying crane species is unknown. We amplified and sequenced 894-bp DNA fragments of CO1 from Grus japonensis (Japanese crane), G. grus (Eurasian crane), G. monacha (hooded crane), G. canadensis (sandhill crane), G. leucogeranus (Siberian crane), and Balearica pavonina (crowned crane), along with those of 15 species obtained from GenBank and DNA barcoding, to construct four algorithms using Tringa stagnatilis, Scolopax rusticola, and T. erythropus as outgroups. The four phylum profiles showed good resolution of the major taxonomic groups. We concluded that reconstruction of the molecular phylogenetic tree can be helpful for classification and that Genetics and Molecular Research 10 (4): 4048-4062 (2011) ©FUNPEC-RP www.funpecrp.com.br mtDNA CO1 sequences for phylogenetic estimates in Grus species 4049 CO1 sequences are suitable for studying the molecular evolution of cranes. -

The Cranes Compiled by Curt D

Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan The Cranes Compiled by Curt D. Meine and George W. Archibald IUCN/SSC Crane Specialist Group IUCN The World Conservation Union IUCN/Species Survival Commission Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Fund and The Cranes: Status Survey & Conservation Action Plan The IUCN/Species Survival Commission Conservation Communications Fund was established in 1992 to assist SSC in its efforts to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, deci- sion-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, occasional papers, news magazine (Species), Membership Directory and other publi- cations are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation; to date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to Specialist Groups. As a result, the Action Plan Programme has progressed at an accelerated level and the network has grown and matured significantly. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and sup- port for species conservation worldwide. The Chicago Zoological Society (CZS) provides significant in-kind and cash support to the SSC, including grants for special projects, editorial and design services, staff secondments and related support services. The President of CZS and Director of Brookfield Zoo, George B. Rabb, serves as the volunteer Chair of the SSC. The mis- sion of CZS is to help people develop a sustainable and harmonious relationship with nature. The Zoo carries out its mis- sion by informing and inspiring 2,000,000 annual visitors, serving as a refuge for species threatened with extinction, developing scientific approaches to manage species successfully in zoos and the wild, and working with other zoos, agencies, and protected areas around the world to conserve habitats and wildlife. -

Hooded Crane (Grus Monachus)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences January 1983 Cranes of the World: Hooded Crane (Grus monachus) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscicranes Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Cranes of the World: Hooded Crane (Grus monachus)" (1983). Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard. 18. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscicranes/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hooded Crane Grus monachus Temminck 1835 Other Vernacular Names. None in general English use; grams, but four fresh eggs averaged 149.6 grams Huan-has (Chinese); Grue-moine (French); Monch- (Christine Sheppard, pers. comm.). skranich (German); Nabe-zuru (Japanese); Chernyi zhuravl (Russian); Grulla capachina (Spanish). Description Range. Breeding range not well known, but currently known to breed only in a few isolated areas of the Adults of both sexes are alike, with the forepart of the USSR, including the Ussuri River and the lower crown unfeathered, red, and covered with black hairlike Amur, in the basin of the middle reaches of the bristles. The upper eyelid is also bare and is horn- Vilyuy, and in the Olekma-Chara uplands. Breed- colored. The rest of the head and neck are white, ing probably also occurs in the upper Nizhnaya sometimes tinged with gray. -

Birds of Indiana

Birds of Indiana This list of Indiana's bird species was compiled by the state's Ornithologist based on accepted taxonomic standards and other relevant data. It is periodically reviewed and updated. References used for scientific names are included at the bottom of this list. ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Anseriformes Anatidae Dendrocygna autumnalis Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Waterfowl: Swans, Geese, and Ducks Dendrocygna bicolor Fulvous Whistling-Duck Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose Anser caerulescens Snow Goose Anser rossii Ross's Goose Branta bernicla Brant Branta leucopsis Barnacle Goose Branta hutchinsii Cackling Goose Branta canadensis Canada Goose Cygnus olor Mute Swan X Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan SE Cygnus columbianus Tundra Swan Aix sponsa Wood Duck Spatula discors Blue-winged Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cinnamon Teal Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mareca strepera Gadwall Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mareca americana American Wigeon Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Anas rubripes American Black Duck Anas fulvigula Mottled Duck Anas acuta Northern Pintail Anas crecca Green-winged Teal Aythya valisineria Canvasback Aythya americana Redhead Aythya collaris Ring-necked Duck Aythya marila Greater Scaup Aythya affinis Lesser Scaup Somateria spectabilis King Eider Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Melanitta perspicillata Surf Scoter Melanitta deglandi White-winged Scoter ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Melanitta americana Black Scoter Clangula hyemalis Long-tailed Duck Bucephala -

Phylogeny of Cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae) Based on Cytochrome-B Dna Sequences

The Auk 111(2):351-365, 1994 PHYLOGENY OF CRANES (GRUIFORMES: GRUIDAE) BASED ON CYTOCHROME-B DNA SEQUENCES CAREY KRAJEWSKIAND JAMESW. FETZNER,JR. • Departmentof Zoology,Southern Illinois University, Carbondale,Illinois 62901-6501, USA ABS?RACr.--DNAsequences spanning 1,042 nucleotide basesof the mitochondrial cyto- chrome-b gene are reported for all 15 speciesand selected subspeciesof cranes and an outgroup, the Limpkin (Aramusguarauna). Levels of sequencedivergence coincide approxi- mately with current taxonomicranks at the subspecies,species, and subfamilial level, but not at the generic level within Gruinae. In particular, the two putative speciesof Balearica (B. pavoninaand B. regulorum)are as distinct as most pairs of gruine species.Phylogenetic analysisof the sequencesproduced results that are strikingly congruentwith previousDNA- DNA hybridization and behavior studies. Among gruine cranes, five major lineages are identified. Two of thesecomprise single species(Grus leucogeranus, G. canadensis), while the others are speciesgroups: Anthropoides and Bugeranus;G. antigone,G. rubicunda,and G. vipio; and G. grus,G. monachus,G. nigricollis,G. americana,and G. japonensis.Within the latter group, G. monachusand G. nigricollisare sisterspecies, and G. japonensisappears to be the sistergroup to the other four species.The data provide no resolutionof branchingorder for major groups, but suggesta rapid evolutionary diversification of these lineages. Received19 March 1993, accepted19 August1993. THE 15 EXTANTSPECIES of cranescomprise the calls.These -

Origin of Three Red-Crowned Cranes Grus Japonensis Found in Northeast Honshu and West Hokkaido, Japan, from 2008 to 2012

NOTE Wildlife Science Origin of Three Red-Crowned Cranes Grus japonensis Found in Northeast Honshu and West Hokkaido, Japan, from 2008 to 2012 Yoshiaki MIURA1), Junya SHIRAISHI1), Akira SHIOMI1), Takio KITAZAWA1), Takeo HIRAGA1), Fumio MATSUMOTO2), Hiroki TERAOKA1,2)* and Hiroyuki MASATOMI2) 1)School of Veterinary Medicine, Rakuno Gakuen University, Ebetsu 069–8501, Japan 2)Tancho Protection Group, Kushiro 085–0036, Japan (Received 19 February 2013/Accepted 12 April 2013/Published online in J-STAGE 26 April 2013) ABSTRACT. The Red-crowned Crane Grus japonensis is an endangered species that has two separate breeding populations, one in the Amur River basin and the other in north and east Hokkaido, Japan. So far, only two (Gj1 and Gj2) and seven (Gj3-Gj9) haplotypes in D-loop of mtDNA were identified in Japan and in the continent, respectively. We obtained feathers from three cranes found in northeast Honshu. The crane in Akita in 2008, which also arrived at west Hokkaido, had a novel haplotype (Gj10). Another crane in Akita in 2009 showed a heteroplasmy (Gj7 and a novel type, Gj12). The third crane in Miyagi in 2010 also showed another type, Gj11. These results suggest that three Red-crowned Cranes appeared in Honshu and west Hokkaido were from the continent. KEY WORDS: continental population, genetic diversity, Hokkaido, island population, Red-crowned (Japanese) Crane. doi: 10.1292/jvms.13-0090; J. Vet. Med. Sci. 75(9): 1241–1244, 2013 The Red-crowned (or Japanese) Crane Grus japonensis is cranes in our previous study [9] as well as a pilot study with one of the most endangered species in the world, with an es- microsatellites [2]. -

Vertebral Formula in Red-Crowned Crane (Grus Japonensis) and Hooded Crane (Grus Monacha)

FULL PAPER Wildlife Science Vertebral Formula in Red-Crowned Crane (Grus japonensis) and Hooded Crane (Grus monacha) Takeo HIRAGA1)*, Haruka SAKAMOTO1), Sayaka NISHIKAWA1), Ippei MUNEUCHI1), Hiromi UEDA1), Masako INOUE2), Ryoji SHIMURA2), Akiko UEBAYASHI2), Nobuhiro YASUDA3), Kunikazu MOMOSE4), Hiroyuki MASATOMI4) and Hiroki TERAOKA1,4) 1)School of Veterinary Medicine, Rakuno Gakuen University, 582 Midori-machi, Ebetsu, Hokkaido 069–8501, Japan 2)Kushiro Zoo, Akan-cho, Kushiro, Hokkaido 085–0201, Japan 3)Department of Veterinary Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Kagoshima University, 1–21–24 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890–0065, Japan 4)NPO Tancho Protection Group, Wakatake-cho, Kushiro, Hokkaido 085–0036, Japan (Received 7 June 2013/Accepted 27 November 2013/Published online in J-STAGE 11 December 2013) ABSTRACT. Red-crowned cranes (Grus japonensis) are distributed separately in the east Eurasian Continent (continental population) and in Hokkaido, Japan (island population). The island population is sedentary in eastern Hokkaido and has increased from a very small number of cranes to over 1,300, thus giving rise to the problem of poor genetic diversity. While, Hooded cranes (Grus monacha), which migrate from the east Eurasian Continent and winter mainly in Izumi, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan, are about eight-time larger than the island population of Red-crowned cranes. We collected whole bodies of these two species, found dead or moribund in eastern Hokkaido and in Izumi, and observed skeletons with focus on vertebral formula. Numbers of cervical vertebrae (Cs), thoracic vertebrae (Ts), vertebrae composing the synsacrum (Sa) and free coccygeal vertebrae (free Cos) in 22 Red-crowned cranes were 17 or 18, 9–11, 13 or 14 and 7 or 8, respectively. -

Migratory Stopover and Wintering Locations in Eastern China Used by White-Naped Cranes Grus Vipio and Hooded Cranes G

FORKTAIL 16 (2000): 93-99 Migratory stopover and wintering locations in eastern China used by White-naped Cranes Grus vipio and Hooded Cranes G. monacha as determined by satellite tracking JAMES HARRIS, SU LIYING, HIROYOSHI HIGUCHI, MUTSUYUKI UETA, ZHANG ZHENGWANG, ZHANG YANYUN and NI XIJUN Conservation efforts for the threatened White-naped Grus vipio and Hooded Cranes G. monacha have focused on breeding and wintering areas, in part because of a lack of information on migratory habitats. From 1991–1993, satellite tracking was used to determine stopover locations for these species. This paper reports on migratory sites in eastern China and also on the Russian side of Lake Khanka, near the international border with China. In addition, satellite tracking documented local crane movements in winter at Poyang Lake. Ground surveys provided valuable supplementation of satellite data. We discuss the conservation implications of our study, particularly the need to expand protected areas for both migratory and wintering habitats. North-east Asia has seven crane species, more than any migration corridors. Six of the seven cranes of northeast other region on earth (Table 1). Like most waterbirds Asia migrate across eastern China; four of these six breeding in northern latitudes, the cranes perform long species are threatened. The threatened White-naped migrations each spring and fall. These migrations pass Crane Grus vipio and Hooded Crane G. monacha nest through some of the most heavily populated areas on along the Russian-Chinese border and winter in earth, including the eastern plains of China. Rapid southern Japan, the Korean Peninsula, and the Chang economic development has created intense pressure on Jiang river basin of southern China (Figure 1).