Closing the Last Chapter of the Atlantic Revolution: the Iß^'J-^S Rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

OECD/IMHE Project Self Evaluation Report: Atlantic Canada, Canada

OECD/IMHE Project Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development Self Evaluation Report: Atlantic Canada, Canada Wade Locke (Memorial University), Elizabeth Beale (Atlantic Provinces Economic Council), Robert Greenwood (Harris Centre, Memorial University), Cyril Farrell (Atlantic Provinces Community College Consortium), Stephen Tomblin (Memorial University), Pierre-Marcel Dejardins (Université de Moncton), Frank Strain (Mount Allison University), and Godfrey Baldacchino (University of Prince Edward Island) December 2006 (Revised March 2007) ii Acknowledgements This self-evaluation report addresses the contribution of higher education institutions (HEIs) to the development of the Atlantic region of Canada. This study was undertaken following the decision of a broad group of partners in Atlantic Canada to join the OECD/IMHE project “Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development”. Atlantic Canada was one of the last regions, and the only North American region, to enter into this project. It is also one of the largest groups of partners to participate in this OECD project, with engagement from the federal government; four provincial governments, all with separate responsibility for higher education; 17 publicly funded universities; all colleges in the region; and a range of other partners in economic development. As such, it must be appreciated that this report represents a major undertaking in a very short period of time. A research process was put in place to facilitate the completion of this self-evaluation report. The process was multifaceted and consultative in nature, drawing on current data, direct input from HEIs and the perspectives of a broad array of stakeholders across the region. An extensive effort was undertaken to ensure that input was received from all key stakeholders, through surveys completed by HEIs, one-on-one interviews conducted with government officials and focus groups conducted in each province which included a high level of private sector participation. -

THE SPECIAL COUNCILS of LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 By

“LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 by Maxime Dagenais Dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree in History. Department of History Faculty of Arts Université d’Ottawa\ University of Ottawa © Maxime Dagenais, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 ii ABSTRACT “LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 Maxime Dagenais Supervisor: University of Ottawa, 2011 Professor Peter Bischoff Although the 1837-38 Rebellions and the Union of the Canadas have received much attention from historians, the Special Council—a political body that bridged two constitutions—remains largely unexplored in comparison. This dissertation considers its time as the legislature of Lower Canada. More specifically, it examines its social, political and economic impact on the colony and its inhabitants. Based on the works of previous historians and on various primary sources, this dissertation first demonstrates that the Special Council proved to be very important to Lower Canada, but more specifically, to British merchants and Tories. After years of frustration for this group, the era of the Special Council represented what could be called a “catching up” period regarding their social, commercial and economic interests in the colony. This first section ends with an evaluation of the legacy of the Special Council, and posits the theory that the period was revolutionary as it produced several ordinances that changed the colony’s social, economic and political culture This first section will also set the stage for the most important matter considered in this dissertation as it emphasizes the Special Council’s authoritarianism. -

Empire Under Strain 1770-1775

The Empire Under Strain, Part II by Alan Brinkley This reading is excerpted from Chapter Four of Brinkley’s American History: A Survey (12th ed.). I wrote the footnotes. If you use the questions below to guide your note taking (which is a good idea), please be aware that several of the questions have multiple answers. Study Questions 1. How did changing ideas about the nature of government encourage some Americans to support changing the relationship between Britain and the 13 colonies? 2. Why did Americans insist on “no taxation without representation,” and why did Britain’s leaders find this request laughable? 3. After a quiet period, the Tea Act caused tensions between Americans and Britain to rise again. Why? 4. How did Americans resist the Tea Act, and why was this resistance important? (And there is more to this answer than just the tea party.) 5. What were the “Intolerable” Acts, and why did they backfire on Britain? 6. As colonists began to reject British rule, what political institutions took Britain’s place? What did they do? 7. Why was the First Continental Congress significant to the coming of the American Revolution? The Philosophy of Revolt Although a superficial calm settled on the colonies for approximately three years after the Boston Massacre, the crises of the 1760s had helped arouse enduring ideological challenges to England and had produced powerful instruments for publicizing colonial grievances.1 Gradually a political outlook gained a following in America that would ultimately serve to justify revolt. The ideas that would support the Revolution emerged from many sources. -

Eight History Lessons Grade 8

Eight History Lessons Grade 8 Submitted By: Rebecca Neadow 05952401 Submitted To: Ted Christou CURR 355 Submitted On: November 15, 2013 INTRODUCTORY ACTIVITY OVERVIEW This is an introductory assignment for students in a grade 8 history class dealing with the Red River Settlement. LEARNING GOAL AND FOCUSING QUESTION - During this lesson students activate their prior knowledge and connections to gain a deeper understanding of the word Rebellion and what requires to set up a new settlement. CURRICULUM EXPECTATIONS - Interpret and analyse information and evidence relevant to their investigations, using a variety of tools. MATERIALS - There are certain terms students will need to understand within this lesson. They are: 1. Emigrate – to leave one place or country in order to settle in another 2. Lord Selkirk – Scottish born 5th Earl of Selkirk, used his money to buy the Hudson’s Bay Company in order to get land to establish a settlement on the Red River in Rupert’s Land in 1812 3. Red River – a river that flows North Dakota north into Lake Winnipeg 4. Exonerate – to clear or absolve from blame or a criminal charge 5. Hudson’s Bay Company – an English company chartered in 1670 to trade in all parts of North America drained by rivers flowing into Hudson’s Bay 6. North West Company – a fur trading business headquartered in Montréal from 1779 to 1821 which competed, often violently, with the Hudson’s Bay Company until it merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821 7. Rupert’s Land – the territories granted by Charles II of England to the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670 and ceded to the Canadian government in 1870 - For research: textbook, computer, dictionaries or whatever you have available to you. -

Chapter 1: Introduction

AN ANALYSIS OF THE 1875-1877 SCARLET FEVER EPIDEMIC OF CAPE BRETON ISLAND, NOVA SCOTIA ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia ___________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ by JOSEPH MACLEAN PARISH Dr. Lisa Sattenspiel, Dissertation Supervisor DECEMBER 2004 © Copyright by Joseph MacLean Parish 2004 All Rights Reserved Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the people of Cape Breton and in particular the people of Chéticamp, both past and present. Your enduring spirits, your pioneering efforts and your selfless approach to life stand out amongst all peoples. Without these qualities in you and your ancestors, none of this would have been possible. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my fiancée Demmarest who has been a constant source of support throughout the process of creating this dissertation and endured my stress with me every step of the way. I will never forget your patience and selflessness. My mother Ginny was a steady source of encouragement and strength since my arrival in Missouri so shortly after the passing of my father. Your love knows no bounds mom. I would also like to thank my close friends who have believed in me throughout my entire academic “career” and supported my choices including, in no particular order, Mickey ‘G’, Alexis Dolphin, Rhonda Bathurst, Michael Pierce, Jason Organ and Ahmed Abu-Dalou. I owe special thanks to my aunt and uncle, Muriel and Earl “Curly” Gray of Sydney, Nova Scotia, and my cousins Wallace, Carole, Crystal and Michelle AuCoin and Auguste Deveaux of Chéticamp, Nova Scotia for being my gracious hosts numerous times throughout the years of my research. -

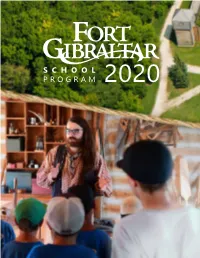

S C H O O L Program

SCHOOL PROGRAM 2020 INTRODUCTION We invite you to learn about Fort Gibraltar’s influence over the cultural development of the Red River settlement. Delve into the lore of the French Canadian voyageurs who paddled across the country, transporting trade-goods and the unique customs of Lower Canada into the West. They married into the First Nations communities and precipitated the birth of the Métis nation, a unique culture that would have a lasting impact on the settlement. Learn how the First Nations helped to ensure the success of these traders by trapping the furs needed for the growing European marketplace. Discover how they shared their knowledge of the land and climate for the survival of their new guests. On the other end of the social scale, meet one of the upper-class managers of the trading post. Here you will get a glimpse of the social conventions of a rapidly changing industrialized Europe. Through hands-on demonstrations and authentic crafts, learn about the formation of this unique community nearly two hundred years ago. Costumed interpreters will guide your class back in time to the year 1815 to a time of immeasurable change in the Red River valley. 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Fort Gibraltar Admission 866, Saint-Joseph St. Guided Tour Managed by: Festival du Voyageur inc. School Groups – $5 per student Phone: 204.237.7692 Max. 80 students, 1.877.889.7692 Free admission for teachers Fax: 204.233.7576 www.fortgibraltar.com www.heho.ca Dates of operation for the School Program Reservations May 11 to June 26, 2019 Guided tours must be booked at least one week before your outing date. -

Leisure Activities in the Colonial Era

PUBLISHED BY THE PAUL REVERE MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION SPRING 2016 ISSUE NO. 122 Leisure Activities in The Colonial Era BY LINDSAY FORECAST daily tasks. “Girls were typically trained in the domestic arts by their mothers. At an early age they might mimic the house- The amount of time devoted to leisure, whether defined as keeping chores of their mothers and older sisters until they recreation, sport, or play, depends on the time available after were permitted to participate actively.” productive work is completed and the value placed on such pursuits at any given moment in time. There is no doubt that from the late 1600s to the mid-1850s, less time was devoted to pure leisure than today. The reasons for this are many – from the length of each day, the time needed for both routine and complex tasks, and religious beliefs about keeping busy with useful work. There is evidence that men, women, and children did pursue leisure activities when they had the chance, but there was just less time available. Toys and descriptions of children’s games survive as does information about card games, dancing, and festivals. Depending on the social standing of the individual and where they lived, what leisure people had was spent in different ways. Activities ranged from the traditional sewing and cooking, to community wide events like house- and barn-raisings. Men had a few more opportunities for what we might call leisure activities but even these were tied closely to home and business. Men in particular might spend time in taverns, where they could catch up on the latest news and, in the 1760s and 1770s, get involved in politics. -

Loyalists in War, Americans in Peace: the Reintegration of the Loyalists, 1775-1800

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 Aaron N. Coleman University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Coleman, Aaron N., "LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800" (2008). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 620. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/620 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERATION Aaron N. Coleman The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2008 LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 _________________________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _________________________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aaron N. Coleman Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Daniel Blake Smith, Professor of History Lexington, Kentucky 2008 Copyright © Aaron N. Coleman 2008 iv ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 After the American Revolution a number of Loyalists, those colonial Americans who remained loyal to England during the War for Independence, did not relocate to the other dominions of the British Empire. -

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY German Immigration to Mainland

The Flow and the Composition of German Immigration to Philadelphia, 1727-177 5 IGHTEENTH-CENTURY German immigration to mainland British America was the only large influx of free white political E aliens unfamiliar with the English language.1 The German settlers arrived relatively late in the colonial period, long after the diversity of seventeenth-century mainland settlements had coalesced into British dominance. Despite its singularity, German migration has remained a relatively unexplored topic, and the sources for such inquiry have not been adequately surveyed and analyzed. Like other pre-Revolutionary migrations, German immigration af- fected some colonies more than others. Settlement projects in New England and Nova Scotia created clusters of Germans in these places, as did the residue of early though unfortunate German settlement in New York. Many Germans went directly or indirectly to the Carolinas. While backcountry counties of Maryland and Virginia acquired sub- stantial German populations in the colonial era, most of these people had entered through Pennsylvania and then moved south.2 Clearly 1 'German' is used here synonymously with German-speaking and 'Germany' refers primar- ily to that part of southwestern Germany from which most pre-Revolutionary German-speaking immigrants came—Cologne to the Swiss Cantons south of Basel 2 The literature on German immigration to the American colonies is neither well defined nor easily accessible, rather, pertinent materials have to be culled from a large number of often obscure publications -

The Montreal Natural History Society's Survey of Rupert's Land, 1827

An Extensive and Unknown Portion of the Empire: The Montreal Natural History Society’s Survey of Rupert’s Land, 1827-1830 Geoffrey Robert Little A Thesis in The Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2015 © Geoffrey Robert Little, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Geoffrey Robert Little Entitled: An Extensive and Unknown Portion of the Empire: The Montreal Natural History Society’s Survey of Rupert’s Land, 1827-1830 and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: ____________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska ____________________ Examiner Dr. Elsbeth Heaman ____________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick ____________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Taylor Approved by ____________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director __________2015 _____________________________ Dean of Faculty ABSTRACT An Extensive and Unknown Portion of the Empire: The Montreal Natural History Society’s Survey of Rupert’s Land, 1827-1830 Geoffrey Robert Little Shortly after it was founded in May 1827, the Montreal Natural History Society constituted an Indian Committee to study the “the native inhabitants...and the Natural History of the Interior, and its fitness for the purposes of commerce and agriculture.” The Interior was Rupert’s Land, the territory to the west and the north of Montreal governed by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). -

From Lower Canadian Colonists to Bermudan Convicts – Political Slavery and the Politics of Unfreedom

“By What Authority Do You Chain Us Like Felons?”: From Lower Canadian Colonists to Bermudan Convicts – Political Slavery and the Politics of Unfreedom Jarett Henderson, Mount Royal University At 3:00 PM on 2 July 1838, Wolfred Nelson stepped, for the first time since his arrest in December 1837, outside the stone walls of the newly built Montreal Gaol. Iron shackles hung from his wrists and ankles. Heavy chains bound him to Robert Bouchette, who, like 515 other Lower Canadian reformers, had been arrested under the auspices of leading an insurrection against the British empire. That July day Nelson, Bouchette, and six other white British subjects – often identified as patriots – began a journey that took them from Montreal to Quebec to Hamilton, the capital of the British penal colony of Bermuda. Their procession from the gaol to the Canada steamer moored in the St. Lawrence provided these eight men one final opportunity to demonstrate their frustration with irresponsible colonial government. The rhetoric of political enslavement once used by Nelson to agitate for reform had been replaced with iron shackles. This symbol of unfreedom was both personal and political. Furthermore, it provides a vivid example of how Nelson, Bouchette, and their fellow compatriots Rodolphe DesRivières, Henri Gauvin, Siméon Marchesseault, Luc Masson, Touissant Goddu, and Bonaventure Viger’s ideas about the reach of empire had encouraged their political engagement and transformed them from loyal to disloyal, from free to unfree, and from civil to uncivil subjects. Though there is little record of the removal of these men from Lower Canada, we must not take this as an indication that their transportation to Bermuda went unnoticed.