Olof Lindahl and the 1770S and 1780S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recession of 1797?

SAE./No.48/February 2016 Studies in Applied Economics WHAT CAUSED THE RECESSION OF 1797? Nicholas A. Curott and Tyler A. Watts Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise What Caused the Recession of 1797? By Nicholas A. Curott and Tyler A. Watts Copyright 2015 by Nicholas A. Curott and Tyler A. Watts About the Series The Studies in Applied Economics series is under the general direction of Prof. Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise ([email protected]). About the Authors Nicholas A. Curott ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of Economics at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana. Tyler A. Watts is Professor of Economics at East Texas Baptist University in Marshall, Texas. Abstract This paper presents a monetary explanation for the U.S. recession of 1797. Credit expansion initiated by the Bank of the United States in the early 1790s unleashed a bout of inflation and low real interest rates, which spurred a speculative investment bubble in real estate and capital intensive manufacturing and infrastructure projects. A correction occurred as domestic inflation created a disparity in international prices that led to a reduction in net exports. Specie flowed out of the country, prices began to fall, and real interest rates spiked. In the ensuing credit crunch, businesses reliant upon rolling over short term debt were rendered unsustainable. The general economic downturn, which ensued throughout 1797 and 1798, involved declines in the price level and nominal GDP, the bursting of the real estate bubble, and a cluster of personal bankruptcies and business failures. -

Empire Under Strain 1770-1775

The Empire Under Strain, Part II by Alan Brinkley This reading is excerpted from Chapter Four of Brinkley’s American History: A Survey (12th ed.). I wrote the footnotes. If you use the questions below to guide your note taking (which is a good idea), please be aware that several of the questions have multiple answers. Study Questions 1. How did changing ideas about the nature of government encourage some Americans to support changing the relationship between Britain and the 13 colonies? 2. Why did Americans insist on “no taxation without representation,” and why did Britain’s leaders find this request laughable? 3. After a quiet period, the Tea Act caused tensions between Americans and Britain to rise again. Why? 4. How did Americans resist the Tea Act, and why was this resistance important? (And there is more to this answer than just the tea party.) 5. What were the “Intolerable” Acts, and why did they backfire on Britain? 6. As colonists began to reject British rule, what political institutions took Britain’s place? What did they do? 7. Why was the First Continental Congress significant to the coming of the American Revolution? The Philosophy of Revolt Although a superficial calm settled on the colonies for approximately three years after the Boston Massacre, the crises of the 1760s had helped arouse enduring ideological challenges to England and had produced powerful instruments for publicizing colonial grievances.1 Gradually a political outlook gained a following in America that would ultimately serve to justify revolt. The ideas that would support the Revolution emerged from many sources. -

Chapter 5 the Americans.Pdf

Washington (on the far right) addressing the Constitutional Congress 1785 New York state outlaws slavery. 1784 Russians found 1785 The Treaty 1781 The Articles of 1783 The Treaty of colony in Alaska. of Hopewell Confederation, which Paris at the end of concerning John Dickinson helped the Revolutionary War 1784 Spain closes the Native American write five years earli- recognizes United Mississippi River to lands er, go into effect. States independence. American commerce. is signed. USA 1782 1784 WORLD 1782 1784 1781 Joseph II 1782 Rama I 1783 Russia annexes 1785 Jean-Pierre allows religious founds a new the Crimean Peninsula. Blanchard and toleration in Austria. dynasty in Siam, John Jeffries with Bangkok 1783 Ludwig van cross the English as the capital. Beethoven’s first works Channel in a are published. balloon. 130 CHAPTER 5 INTERACT WITH HISTORY The year is 1787. You have recently helped your fellow patriots overthrow decades of oppressive British rule. However, it is easier to destroy an old system of government than to create a new one. In a world of kings and tyrants, your new republic struggles to find its place. How much power should the national government have? Examine the Issues • Which should have more power—the states or the national government? • How can the new nation avoid a return to tyranny? • How can the rights of all people be protected? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 5 links for more information about Shaping a New Nation. 1786 Daniel Shays leads a rebellion of farmers in Massachusetts. 1786 The Annapolis Convention is held. -

Leisure Activities in the Colonial Era

PUBLISHED BY THE PAUL REVERE MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION SPRING 2016 ISSUE NO. 122 Leisure Activities in The Colonial Era BY LINDSAY FORECAST daily tasks. “Girls were typically trained in the domestic arts by their mothers. At an early age they might mimic the house- The amount of time devoted to leisure, whether defined as keeping chores of their mothers and older sisters until they recreation, sport, or play, depends on the time available after were permitted to participate actively.” productive work is completed and the value placed on such pursuits at any given moment in time. There is no doubt that from the late 1600s to the mid-1850s, less time was devoted to pure leisure than today. The reasons for this are many – from the length of each day, the time needed for both routine and complex tasks, and religious beliefs about keeping busy with useful work. There is evidence that men, women, and children did pursue leisure activities when they had the chance, but there was just less time available. Toys and descriptions of children’s games survive as does information about card games, dancing, and festivals. Depending on the social standing of the individual and where they lived, what leisure people had was spent in different ways. Activities ranged from the traditional sewing and cooking, to community wide events like house- and barn-raisings. Men had a few more opportunities for what we might call leisure activities but even these were tied closely to home and business. Men in particular might spend time in taverns, where they could catch up on the latest news and, in the 1760s and 1770s, get involved in politics. -

Peasantry and the French Revolution

“1st. What is the third estate? Everything. 2nd. What has it been heretofore in the political order? Nothing. 3rd. What does it demand? To become something therein.” -Abbe Sieyes 1789 Pre-Revolution • Louis XVI came to the throne in the midst of a serious financial crisis • France was nearing bankruptcy due to the outlays that were outpacing income • A new tax code was implemented under the direction of Charles Alexandre de Calonne • This proposal included a land tax • Issues with the Three Estates and inequality within it Peasant Life pre-Revolution • French peasants lived better than most of their class, but were still extremely poor • 40% worked land, but it was subdivided into several small plots which were shared and owned by someone else • Unemployment was high due to the waning textile industry • Rent and food prices continued to rise • Worst harvest in 40 years took place during the winter of 1788-89 Peasant Life pre-Revolution • The Third Estate, which was the lower classes in France, were forced by the nobility and the Church to pay large amounts in taxes and tithes • Peasants had experienced a lot of unemployment during the 1780s because of the decline in the nation’s textile industry • There was a population explosion of about 25-30% in roughly 90 years that did not coincide with a rise in food production Direct Causes of the Revolution • Famine and malnutrition were becoming more common as a result of shortened food supply • Rising bread prices contributes to famine • France’s near bankruptcy due to their involvement in various -

The Constitutional Status of Women in 1787

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 6 Issue 1 Article 3 June 1988 The Constitutional Status of Women in 1787 Mary Beth Norton Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Mary B. Norton, The Constitutional Status of Women in 1787, 6(1) LAW & INEQ. 7 (1988). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol6/iss1/3 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. The Constitutional Status of Women in 1787 Mary Beth Norton* I am tempted to make this presentation on the constitutional status of women in 1787 extremely brief. That is, I could accu- rately declare that "women had no status in the Constitution of 1787" and immediately sit down to listen to the comments of the rest of the panelists here this morning. However, I was undoubt- edly invited here to say more than that, and so I shall. If one looks closely at the words of the original Constitution, the term "man" or "men" is not used; rather, "person," "persons" and "people" are the words of choice. That would seem to imply that the Founding Fathers intended to include women in the scope of their docu- ment. That such an assumption is erroneous, however, was demonstrated in a famous exchange between Abigail and John Ad- ams in 1776. Although John Adams was not present at the Consti- tutional Convention, his attitudes toward women were certainly representative of the men of his generation. In March, 1776, when it had become apparent that indepen- dence would soon be declared, -

355 Adelman, Joseph. Revolutionary Networks: the Business And

Book Reviews Rothstein, Richard. 2017. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. Adelman, Joseph. Revolutionary Networks: The Business and Politics of Printing the News, 1763-1789. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019. 280 Pp. In Revolutionary Networks, colonial newspapers and the men and women behind the presses dominate the headlines. Joseph Adelman explores the oft overlooked business of printing in colonial America and how the industry influenced the American Revolution and the formation of the United States. He attempts to determine how colonial printers, most located in the major ports and towns of British North America, conducted the everyday business of printing and disseminating the news in the politically turbulent period of the late 1760s, 1770s, and 1780s. Colonial printers flowed between the working class and elite society, forming information and business networks that spanned the entire Atlantic Ocean. As a result, printers developed enormous influence by curating the news; they played a central role in the political turmoil of the American Revolution and development of the United State Constitution. Adelman charts the role of printers in Britain’s North American colonies in shaping the political economy of colonial America and the early United States in six chapters, an introduction, and a conclusion. Few authors attempt to place the American Revolution as a secondary focus, but Adelman does so successfully, placing printers and their business practices at the forefront of the political and social developments. He begins, in chapter one, with a description of the economic and business practices of printers in the colonies, including mundane details such as advertising and subscription rates. -

Loyalists in War, Americans in Peace: the Reintegration of the Loyalists, 1775-1800

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 Aaron N. Coleman University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Coleman, Aaron N., "LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800" (2008). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 620. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/620 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERATION Aaron N. Coleman The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2008 LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 _________________________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _________________________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aaron N. Coleman Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Daniel Blake Smith, Professor of History Lexington, Kentucky 2008 Copyright © Aaron N. Coleman 2008 iv ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 After the American Revolution a number of Loyalists, those colonial Americans who remained loyal to England during the War for Independence, did not relocate to the other dominions of the British Empire. -

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY German Immigration to Mainland

The Flow and the Composition of German Immigration to Philadelphia, 1727-177 5 IGHTEENTH-CENTURY German immigration to mainland British America was the only large influx of free white political E aliens unfamiliar with the English language.1 The German settlers arrived relatively late in the colonial period, long after the diversity of seventeenth-century mainland settlements had coalesced into British dominance. Despite its singularity, German migration has remained a relatively unexplored topic, and the sources for such inquiry have not been adequately surveyed and analyzed. Like other pre-Revolutionary migrations, German immigration af- fected some colonies more than others. Settlement projects in New England and Nova Scotia created clusters of Germans in these places, as did the residue of early though unfortunate German settlement in New York. Many Germans went directly or indirectly to the Carolinas. While backcountry counties of Maryland and Virginia acquired sub- stantial German populations in the colonial era, most of these people had entered through Pennsylvania and then moved south.2 Clearly 1 'German' is used here synonymously with German-speaking and 'Germany' refers primar- ily to that part of southwestern Germany from which most pre-Revolutionary German-speaking immigrants came—Cologne to the Swiss Cantons south of Basel 2 The literature on German immigration to the American colonies is neither well defined nor easily accessible, rather, pertinent materials have to be culled from a large number of often obscure publications -

Constitution of the United States of America, As Amended

110TH CONGRESS DOCUMENT " ! 1st Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES No. 110–50 THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA As Amended Unratified Amendments Analytical Index E PL UR UM IB N U U S PRESENTED BY MR. BRADY OF PENNSYLVANIA July 25, 2007 • Ordered to be printed UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-001 [ISBN 978–0–16–079091–1] VerDate Aug 31 2005 11:11 Dec 10, 2007 Jkt 036932 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5229 Sfmt 5229 E:\HR\OC\36932.XXX 36932 cprice-sewell on PROD1PC72 with HEARING E:\seals\congress.#15 House Doc. 110–50 The printing of the revised version of The Constitution of the United States of America As Amended (Document Size) is hereby ordered pursuant to H. Con. Res. 190 as passed on July 25, 2007, 110th Congress, 1st Session. This document was compiled at the di- rection of Chairman Robert A. Brady of the Joint Committee on Printing, and printed by the U.S. Government Printing Office. (ii) VerDate Aug 31 2005 11:19 Dec 10, 2007 Jkt 036932 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 7601 Sfmt 7601 E:\HR\OC\932.CC 932 cprice-sewell on PROD1PC72 with HEARING CONTENTS Historical Note ......................................................................................................... v Text of the Constitution .......................................................................................... 1 Amendments -

Colonists Respond to the Outbreak of War, 1774-1775, Compilation

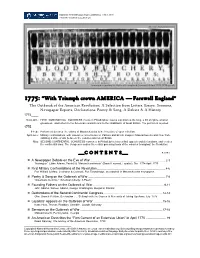

MAKING THE REVOLUTION: AMERICA, 1763-1791 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION American Antiquarian Society broadside reporting the Battle of Lexington & Concord,19 April 1775; 1775 (detail) 1775: “With Triumph crown AMERICA Farewell England” The Outbreak of the American Revolution: A Selection from Letters, Essays, Sermons, Newspaper Reports, Declarations, Poetry & Song, A Debate & A History 1774____* Sept.-Oct.: FIRST CONTINENTAL CONGRESS meets in Philadelphia; issues a petition to the king, a bill of rights, a list of grievances, and letters to the American colonists and to the inhabitants of Great Britain. The petition is rejected. 1775____ 9 Feb.: Parliament declares the colony of Massachusetts to be in a state of open rebellion. April-June: Military confrontations with casualties occur between Patriots and British troops in Massachusetts and New York, initiating a state of war between the colonies and Great Britain. May: SECOND CONTINENTAL CONGRESS convenes in Philadelphia, issues final appeals and declarations, and creates the continental army. The Congress remains the central governing body of the colonies throughout the Revolution. PAGES ___CONTENT S___ A Newspaper Debate on the Eve of War ............................................................................. 2-3 “Novanglus” (John Adams, Patriot) & “Massachusettensis” (Daniel Leonard, Loyalist), Dec. 1774-April 1775 First Military Confrontations of the Revolution...................................................................... 4-6 Fort William & Mary, Lexington & Concord, -

Few Americans in the 1790S Would Have Predicted That the Subject Of

AMERICAN NAVAL POLICY IN AN AGE OF ATLANTIC WARFARE: A CONSENSUS BROKEN AND REFORGED, 1783-1816 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jeffrey J. Seiken, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor John Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Margaret Newell _______________________ Professor Mark Grimsley Advisor History Graduate Program ABSTRACT In the 1780s, there was broad agreement among American revolutionaries like Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton about the need for a strong national navy. This consensus, however, collapsed as a result of the partisan strife of the 1790s. The Federalist Party embraced the strategic rationale laid out by naval boosters in the previous decade, namely that only a powerful, seagoing battle fleet offered a viable means of defending the nation's vulnerable ports and harbors. Federalists also believed a navy was necessary to protect America's burgeoning trade with overseas markets. Republicans did not dispute the desirability of the Federalist goals, but they disagreed sharply with their political opponents about the wisdom of depending on a navy to achieve these ends. In place of a navy, the Republicans with Jefferson and Madison at the lead championed an altogether different prescription for national security and commercial growth: economic coercion. The Federalists won most of the legislative confrontations of the 1790s. But their very success contributed to the party's decisive defeat in the election of 1800 and the abandonment of their plans to create a strong blue water navy.