Dr Oon Chong Teik: Shuttlecock and Stethoscope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

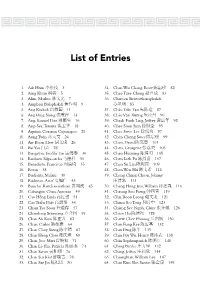

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

I N T H E S P I R I T O F S E R V I

The Old Frees’ AssOCIatION, SINGAPORE Registered 1962 Live Free IN THE SPIRIT OF SERVING Penang Free School 1816-2016 Penang Free School in August 2015. The Old Frees’ AssOCIatION, SINGAPORE Registered 1962 www.ofa.sg Live Free IN THE SPIRIT OF SERVING AUTHOR Tan Chung Lee PUBLISHER The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore PUBLISHER The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore 3 Mount Elizabeth #11-07, Mount Elizabeth Medical Centre Singapore 228510 AUTHOR Tan Chung Lee OFAS COFFEE-TABLE BOOK ADJUDICATION PANEL John Lim Kok Min (co-chairman) Tan Yew Oo (co-chairman) Kok Weng On Lee Eng Hin Lee Seng Teik Malcolm Tan Ban Hoe OFAS COFFEE-TABLE BOOK WORKGROUP Alex KH Ooi Cheah Hock Leong The OFAS Management Committee would like to thank Gabriel Teh Choo Thok Editorial Consultant: Tan Chung Lee the family of the late Chan U Seek and OFA Life Members Graphic Design: ST Leng Production: Inkworks Media & Communications for their donations towards the publication of this book. Printer: The Phoenix Press Sdn Bhd 6, Lebuh Gereja, 10200 Penang, Malaysia The committee would also like to acknowledge all others who PHOTOGRAPH COPYRIGHT have contributed to and assisted in the production of this Penang Free School Archives Lee Huat Hin aka Haha Lee, Chapter 8 book; it apologises if it has inadvertently omitted anyone. Supreme Court of Singapore (Judiciary) Family of Dr Wu Lien-Teh, Chapter 7 Tan Chung Lee Copyright © 2016 The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore. -

The Transition and Transformation of Badminton Into a Globalized Game

Title The transition and transformation of badminton into a globalized game, 1893-2012: A study of the trials and tribulations of Malaysian badminton players competing for Thomas Cup and Olympic gold medals Author(s) Lim Peng Han Source 8th International Malaysian Studies Conference (MSC8), Selangor, Malaysia, 9 - 11 July 2012 Organised by Malaysian Social Science Association © 2012 Malaysian Social Science Association Citation: Lim, P. H. (2012). The transition and transformation of badminton into a globalized game: A study of the trials and tribulations of Malaysian badminton players competing for Thomas Cup and Olympic gold medals. In Mohd Hazim Shah & Saliha Hassan (Eds.), MSC8 proceedings: Selected full papers (pp. 172 - 187). Kajang, Selangor: Malaysian Social Science Association. Archived with permission from the copyright owner. 4 The Transition and Transformation of Badminton into a Globalised Game, 1893-2012: A Study on the Trials and Tribulations of Malaysian Badminton Players Competing for Thomas Cup and the Olympic Gold Medals Lim Peng Han Department of Information Science Loughborough University Introduction Badminton was transformed as a globalised game in four phases. The first phase began with the founding of the International Badminton Federation in 1934 and 17 badminton associations before the Second World War. The second phase began after the War with the first Thomas Cup contest won by Malaya in 1949. From 1946 to 1979, Malaysia won the Cup 4 times and Indonesia, 7 times. In 1979 twenty-six countries competed for the Cup. The third phase began with China's membership into the IBF in 1981. From 1982 to 2010 China won the Thomas Cup 8 times, Indonesia won 6 times and Malaysia, only once. -

History of Badminton

Facts and Records History of Badminton In 1873, the Duke of Beaufort held a lawn party at his country house in the village of Badminton, Gloucestershire. A game of Poona was played on that day and became popular among British society’s elite. The new party sport became known as “the Badminton game”. In 1877, the Bath Badminton Club was formed and developed the first official set of rules. The Badminton Association was formed at a meeting in Southsea on 13th September 1893. It was the first National Association in the world and framed the rules for the Association and for the game. The popularity of the sport increased rapidly with 300 clubs being introduced by the 1920’s. Rising to 9,000 shortly after World War Π. The International Badminton Federation (IBF) was formed in 1934 with nine founding members: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Denmark, Holland, Canada, New Zealand and France and as a consequence the Badminton Association became the Badminton Association of England. From nine founding members, the IBF, now called the Badminton World Federation (BWF), has over 160 member countries. The future of Badminton looks bright. Badminton was officially granted Olympic status in the 1992 Barcelona Games. Indonesia was the dominant force in that first Olympic tournament, winning two golds, a silver and a bronze; the country’s first Olympic medals in its history. More than 1.1 billion people watched the 1992 Olympic Badminton competition on television. Eight years later, and more than a century after introducing Badminton to the world, Britain claimed their first medal in the Olympics when Simon Archer and Jo Goode achieved Mixed Doubles Bronze in Sydney. -

Med Stor Styrke 1

En BRITGOODS behersker alle slag... med stor styrke 1 2 Bedaktion: Knud Lunøe (ansvarshavende), P. Andersensvej 3, København F. Telf. Gothåb 1952 y (efter kl. 17). Giro 286 77. Ib Larsen, Borgbjergsvej 45, København SV. Telf. Eva 6720 (bedst kl. 17— 18). * Abonnementstegning, annoncetegning og ekspedition: Ib Larsen, ☆ Badminton udkommer een gang i august, september, april og maj — og to gange i oktober, novem ber, december, januar, februar og marts. ☆ Arsabonnement kr. 10,00. 16 numre. ☆ Eftertryk kun tilladt med kildeangivelse. ☆ Tryk: Folketidendes Bogtrykkeri, Søgade 4, Ringsted, telf. nr. 2. ☆ Faste medarbejdere: Poul Pedersen, Fyn, J. P. Kristen sen, Sjælland, N. P. Andersen, Bornholm, Ove E. Olsen, Lolland- Falster, og Ib Henry Hansen, Ma laya. ☆ Medarbejdere ved dette nummer: H. J. Guldbrandsen, Jørgen Hage man, Jørgen Hammergaard Han sen, Bjørn Holst-Christensen, Arne Huss, Poul-Erik Nielsen,John Ny gård, Jørgen Brix Steby. ☆ Indhold: Side Glasgow ..................................... 6 All-England .............................. 10 Tyske mesterskaber ................. 12 Nordskotske mesterskaber ...... 14 Ystad-Spelen ............................. 14 Vejle 25 år ................................ 15 København ................................ 16 Jylland ........................................ 18 Fyn ................................... 21 Officielle meddelelser .............. 22 Sjælland ..................................... 24 Vordingborg ............................. 25 Uber Cup .................................. 26 To af -

Speech by Tan Eng Liang, Chairman, Singapore Sports

Ace. No. NARC SPEECHBY TAN ENGLIANG, CHAIRMAN,SINGAPORE SPORTS COUNCIL, AT THE CHEQUEPRESENTATION OF THEF & N BADMINTONTRAINING SCHEME AT THE NATIONALSTADIUM THEATRETTEON 28 FEBRUARY1981 AT 11.00 AM The F & N Badminton Training Schemewill be 10 years old this year. It has the distinction of pioneering the sport training scheme concept. Today, there are eight other schemes administered by the Singapore Sports Council (SSC), patterned on the training format first a used by badminton. What has the F & N Schemecontributed to badminton? Has the Scheme attained its objectives? These questions and others have often been asked by players and officials, alike. I think that it is natural for anyone, concerned with the growth of badminton in Singapore, to come up with such questions. After all, not only huge sums of money have been invested in the scheme, but much time and effort have been spent in its organisation. Also, coaches end trainees have sacrificed a lot of their leisure time to be involved in the scheme. Without having to go into details, I can say without any reservation here that the badminton contribution of the F & N Schemehas been immense. For one thing, the schemehas consistently fed the national and youth training squads of the Singapore Badminton Association (SBA) with promising end skilled players- For another, the overall quality of young players in the Republic has improved since the scheme's inception, although none of the players has yet to make the inter- national grade. 2/... 2 Recently, an article in the NewNation painted a gloomy picture of the F & N Schemeand suggested that the schemewas "entrenched in a scrap heap". -

1967 P I OLLHD M

har finalister i alle klasser - se dem hos Rådhuspladsen, Kbhvn. V. Tlf. 1212 34 Gladsaxe Møllevej 14, Søb. }CAhllAD AM “ AUT FORD-FORHANDLER Tlf. 6912 34 Herlev Hovedgade 97 - 99 Hovedvejen 149, Glostrup Islevdalvej 100, Rødovre Tlf. 94 85 33 Tlf. 4512 34 Tlf. 94 76 88 Lyøvej 20, Frederiksberg Amager Landevej 102-104 Røde Mellemvej 6, Kbh. S Tlf. FA 78 88 Tlf. 51-12 34 Tlf. 55 54 56 2 BADMINTON officielt organ for Dansk Badminton Forbund under Dansk Idræts-Forbund og The International Badminton Federation ☆ Bedaktion: Knud Lunøe (ansvarshavende), P. Andersensvej 3, 2000 København F. Tlf. (01) Gothåb 8019 (eft. kl. 18) Giro 286 77. ☆ DBF’s kontor: Vester Voldgade 11, 1552 Køben- havn V. Tlf. (01) 1175 38. Åbent tirsdag og torsdag kl. 10-13. ☆ Abonnementstegning og ekspedition: DBF’s kontor. * Annoncetegning: Annoncechef Henry Jessen, Bladforlagene, Dr. Tværgade 30, 1302 København K. Tlf. (01) Minerva 8666. ☆ Årsabonnement kr. 20,00 + 10 % FEJLSLAG - NO SHOT moms. — 12 numre. Under det danske Thomas Cup-holds rejse til det fje rne Østen havde jeg ☆ rig lejlighed til at konstatere, hvor forskellig fo rtolkningen af den så for Eftertryk kun tilladt med kætrede „no shot regel“ er; med den engelske og den østerlandske fortolk kildeangivelse. ning som de diametrale modsætninger. Problemet diskuteres jo meget over ☆ alt, hvor man spiller badminton, og det må betegnes som direkte katastro Tryk: falt, at der hersker så stor uklarhed på et for spillet så afgørende punkt. Folketidendes Bogtrykkeri, Søgade 4, 4100 Ringsted. I det meste af Europa, specielt i England, fortolke s reglen derhen, at næ Tlf. -

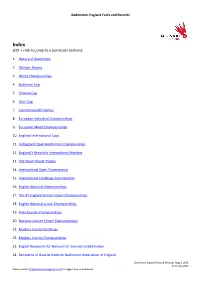

Facts and Records

Badminton England Facts and Records Index (cltr + click to jump to a particular section): 1. History of Badminton 2. Olympic Games 3. World Championships 4. Sudirman Cup 5. Thomas Cup 6. Uber Cup 7. Commonwealth Games 8. European Individual Championships 9. European Mixed Championships 10. England International Caps 11. All England Open Badminton Championships 12. England’s Record in International Matches 13. The Stuart Wyatt Trophy 14. International Open Tournaments 15. International Challenge Tournaments 16. English National Championships 17. The All England Seniors’ Open Championships 18. English National Junior Championships 19. Inter-County Championships 20. National Leisure Centre Championships 21. Masters County Challenge 22. Masters County Championships 23. English Recipients for Honours for Services to Badminton 24. Recipients of Awards made by Badminton Association of England Badminton England Facts & Records: Page 1 of 86 As at May 2021 Please contact [email protected] to suggest any amendments. Badminton England Facts and Records 25. English recipients of Awards made by the Badminton World Federation 1. The History of Badminton: Badminton House and Estate lies in the heart of the Gloucestershire countryside and is the private home of the 12th Duke and Duchess of Beaufort and the Somerset family. The House is not normally open to the general public, it dates from the 17th century and is set in a beautiful deer park which hosts the world-famous Badminton Horse Trials. The Great Hall at Badminton House is famous for an incident on a rainy day in 1863 when the game of badminton was said to have been invented by friends of the 8th Duke of Beaufort. -

Maailmameistrivõistlused Sulgpallis. Meeste Paarismäng

MAAILMAMEISTRIVÕISTLUSED SULGPALLIS. MEESTE PAARISMÄNG Jrk Aasta & võistluspaik Riik Kuld Riik Hõbe Riik Pronksid 1977 Tjun TJUN Christian HADINATA Bengt FRÖMAN Ray STEVENS 1 INA INA SWE ENG Malmö (Swe) Johan WAHJUDI Ade CHANDRA Thomas KIHLSTRÖM Mike TREDGETT F: 15:6, 15:4 PF T/F: 7:15, 11:15 PF H/C: 8:15, 10:15 1980 Christian HADINATA Hariamanto KARTONO Misbun SIDEK Flemming DELFS 2 INA INA MAS DEN Jakarta (Ina) Ade CHANDRA Rudy HERYANTO Jalani SIDEK Steen SKOVGAARD F: 5:15, 15:5, 15:7 PF C/H: 9:15, 10:15 PF K/H: 7:15, 7:15 1983 Steen FLADBERG Martin DEW Christian HADINATA Joo-Bong PARK 3 DEN ENG INA KOR Kopenhaagen (Den) Jesper HELLEDIE Mike TREDGETT Bobby ERTANTO Eun-Ku LEE F: 15:10, 15:10 PF H/E: 16:18, 11:15 PF D/T: 8:15, 15:2, 4:15 1985 Joo-Bong PARK Yongbo LI Liem Swie KING Mark CHRISTENSEN 4 KOR CHN INA DEN Calgary (Can) Moon-Soo KIM Bingyi TIAN Hariamanto KARTONO Michael KJELDSEN F: 5:15, 15:7, 15:9 PF P/K: 11:15, 15:17 PF L/T: 16:18, 18:14, 3:15 1987 Yongbo LI Jalani SIDEK Jens Peter NIERHOFF Joo-Bong PARK 5 CHN MAS DEN KOR Peking (Chn) Bingyi TIAN Razif SIDEK Michael KJELDSEN Moon-Soo KIM F: 15:2, 8:15, 15:9 PF L/T: 4:15, 4:15 PF S/S: 16:17, 4:15 1989 Yongbo LI Hongyong CHEN Jalani SIDEK Rudy GUNAWAN 6 CHN CHN MAS INA Jakarta (Ina) Bingyi TIAN Kang CHEN Razif SIDEK Eddy HARTONO F: 15:3, 15:12 PF L/T: 10:15, 9:15 PF C/C: 11:15, 7:15 1991 Joo-Bong PARK Jon HOLST-CHRISTENSEN Bagus SETIADI Yongbo LI 7 KOR DEN INA CHN Kopenhaagen (Den) Moon-Soo KIM Thomas LUND Imay HENDRA Bingyi TIAN F: 15:10, 12:15, 17:16 PF P/K: 2:15, 12:15 PF -

2001-2002 02.Pdf

DBFs hovedsponsor: DBFs officielle boldleverandør: In d h o ld 1: jREALKREDIT Fokus på en hold kamp: ........................ Danmark Ungdomsturnering i Hillerod:................... Portræt af sportschefen: .... Breddekonsulen- ternes side: .... Haderslev er vært for DM :........... 12-13 Badminton-bladet har fået Det siger reglerne: . 15 to elektroniske brødre Program for Realkredit Danmark Open:. 17-39 Du sidder lige nu med sæsonens største blad, der ud over det sædvanlige stof også Tag med til M asters :. 41 rummer en masse om verdens største badm intonturnering - Realkredit Danm ark Veteranturnering på Open. Alligevel er der som sædvanlig meget stof, vi ikke har plads til. Lanzarote:............. 42-43 M en på en måde lysner det. Lillerød Elite Grand Badm inton-bladet har nemlig fået to elektroniske brødre: Et nyhedsbrev på e-mail Prix:........................ og nyhederne på DBFs hjemmeside. Sammen udgør de, hvad vi kalder DBFs nyheds M ellem 2. og service. 3. sæ t: ..................... 46-47 Nyhederne på DBFs hjem m eside har ganske vist eksisteret i flere år. D et nye er, at ØBD får bredde- man nu kan abonnere på dem. Gør man det, får man en e-mail, hver gang der lægges konsulent:................ en nyhed på w w w .badminton.dk. E-mailen fortæller ko rt, hvad nyheden går ud på og Øvelse fra har et kvik-link til resten af nyheden på DBFs hjem meside. Træningsskolen: . .. 5 0 Helt splinternyt er im idlertid det elektroniske nyhedsbrev. Også det består i en e-mail, m en til forskel fra nyhedsbrevet er det ret langt. Nyhedsbrevet kan m an også DBSs øvrige sponsorer: abonnere på. -

Bdo International Directory 2017

International Directory 2017 Latest version updated 5 July 2017 1 ABOUT BDO BDO is an international network of public accounting, tax and advisory firms, the BDO Member Firms, which perform professional services under the name of BDO. Each BDO Member Firm is a member of BDO International Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee. The BDO network is governed by the Council, the Global Board and the Executive (or Global Leadership Team) of BDO International Limited. Service provision within the BDO network is coordinated by Brussels Worldwide Services BVBA, a limited liability company incorporated in Belgium with VAT/BTW number BE 0820.820.829, RPR Brussels. BDO International Limited and Brussels Worldwide Services BVBA do not provide any professional services to clients. This is the sole preserve of the BDO Member Firms. Each of BDO International Limited, Brussels Worldwide Services BVBA and the member firms of the BDO network is a separate legal entity and has no liability for another such entity’s acts or omissions. Nothing in the arrangements or rules of BDO shall constitute or imply an agency relationship or a partnership between BDO International Limited, Brussels Worldwide Services BVBA and/or the member firms of the BDO network. BDO is the brand name for the BDO network and all BDO Member Firms. BDO is a registered trademark of Stichting BDO. © 2017 Brussels Worldwide Services BVBA 2 2016* World wide fee Income (millions) EUR 6,844 USD 7,601 Number of countries 158 Number of offices 1,401 Partners 5,736 Professional staff 52,486 Administrative staff 9,509 Total staff 67,731 Web site: www.bdointernational.com (provides links to BDO Member Firm web sites world wide) * Figures as per 30 September 2016 including exclusive alliances of BDO Member Firms. -

Ferry Sonneville

FERRY SONNEVILLE _. Karya dan Pengabdiannya MILIK DEPDIKBUD TIDAK DIPERDAGANGKAN FERRY SONNEVILLE Karya dan Pengabdiannya Oleh: Wisnu Subagyo p . 1 Nomor lnduk : I Tanggal ii 0 ,_DEC 20W DEPARTEMEN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN DIREKTORAT SEJARAH DAN NILAI TRADISIONAL PROYEK INVENTARISASI DAN DOKUMENTASI SEJARAH NASIONAL JAKARTA 1985 SAMBUTAN DIREKTUR JENDERAL KEBUDAY AAN Proyek lnventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Sejarah Nasional (IDSN) yang berada pada Direktorat Sejarah dan Nilai Tradi sional Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan telah berhasil menerbitkan seri buku-buku biografi tokoh dan pahlawan nasional. Saya menyambut dengan gembira hasil penerbitan tersebut. Buku-buku tersebut dapat diselesaikan berkat adanya kerja sama antara para penulis dengan tenaga-tenaga di dalam proyek. Karena baru merupakan langkah pertama, maka dalam buku-buku hasil Proyek IDSN itu masih terdapat kelemahan dan kekurangan. Diharapkan hal itu dapat disempurnakan pada masa yang akan datang. Usaha penulisan buku-buku kesejarahan wajib kita ting katkan untuk memupuk, memperkaya dan memberi corak pa da kebudayaan nasional dengan tetap memelihara dan mem bina tradisi dan peninggalan sejarah yang mempunyai nilai perjuangan bangsa, kebanggaan serta kemanfaatan nasional. Saya meng1'arapkan dengan terbitnya buK.u-buku ini da pat menarribah sarana penelitian dan kepustakaan yang diperlu kan untuk pembangunan bangsa dan negara, khususnya pem- iii bangunan kebudayaan. Akhirnya saya mengucapkan terima kasih kepada semua pihak yang telah membantu penerbitan ini. Jakarta, Desember 1984 Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan )f M� Prof. Dr. Haryati Soebadio NIP. 1301191 23 iv KATA PENGANTAR Proyek lnventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Sejarah Nasional merupakan salah satu proyek dalam lingkungan Direktorat Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudaya an, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, yang antara lain mengerjakan penulisan biografi "tokoh" yang telah berjasa da lam masyarakat.