Canterbury Christ Church University's Repository of Research Outputs Http

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration Into the Modern Clarinet Studio

UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones 5-1-2015 The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio Jennifer Beth Iles University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Music Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Iles, Jennifer Beth, "The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio" (2015). UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones. Paper 2367. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Scholarship@UNLV. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses/ Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE BASS CLARINET: SUPPORT FOR ITS INTEGRATION INTO THE MODERN CLARINET STUDIO By Jennifer Beth Iles Bachelor of Music Education McNeese State University 2005 Master of Music Performance University of North Texas 2008 A doctoral document submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada Las Vegas May 2015 We recommend the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Jennifer Iles entitled The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music Marina Sturm, D.M.A., Committee Chair Cheryl Taranto, Ph.D., Committee Member Stephen Caplan, D.M.A., Committee Member Ken Hanlon, D.M.A., Committee Chair Margot Mink Colbert, B.S., Graduate College Representative Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D., Interim Dean of the Graduate College May 2015 ii ABSTRACT The bass clarinet of the twenty-first century has come into its own. -

EPARM Conference 2020 16-18 April, Royal Academy of Music, London

European Platform for Artistic Research in Music EPARM Conference 2020 16-18 April, Royal Academy of Music, London PROGRAMME Thursday, 16th April Time Activity Location REGISTRATION 13.30 Informal Networking – Coffee available 14:30 – 15:30 Guided Tour of the Academy Opening Event Music Introduction Official Welcome by: 15:45 – 16.30 - Jonathan Freeman-Attwood, Principal of the Royal Dukes Hall Academy of Music - Stefan Gies, CEO of the AEC - Stephen Broad, EPARM Chair Plenary Session I – Keynote by Timothy Jones 16.30 – 17.30 Dukes Hall Moderated by David Gorton 17.30 –18:00 Networking with Refreshments 18:00 – 19:00 Concert 19:00 – 20:00 Reception L8 NITE Performance I A Concert Room Ghost Trance Solo’s: a solo interpretation of Anthony Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music, Kobe Van Cauwenberghe, Royal Conservatoire, Antwerp, Belgium 20:00 – 20:30 L8 NITE Performance I B David Josefowitz Recital Hall Fantasía quasi Sonata: an “in-version” of Beethoven’s Op. 27 No. 2, Luca Chiantore, ESMUC - Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya), Barcelona, Spain L8 NITE Performances I C Angela Burgess Recital Hall LEMUR: Collective Artistic Research within an Ensemble, Francis Michael Duch, NTNU – Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway 20:30 – 20:45 Break to allow room change L8 NITE Performances II A Concert Room Ensemble 1604 presents ...shadows that in darkness dwell…, Timothy Cooper, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Glasgow, UK 20:45 – 21:15 L8 NITE Performances II B David Josefowitz Recital Hall Love at first sound: engaging -

Dissertation 3.19.2021

Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Timothy Salzman, Chair David Rahbee Benjamin Lulich Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music © Copyright 2021 Caitlin Beare University of Washington Abstract Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Timothy Salzman School of Music The exploration and implementation of new timbral possibilities and techniques over the past century have redefined approaches to clarinet performance and pedagogy. As the body of repertoire involving nontraditional, or “extended,” clarinet techniques has grown, so too has the pedagogical literature on contemporary clarinet performance, yielding method books, dissertations, articles, and online resources. Despite the wealth of resources on extended clarinet techniques, however, few authors offer accessible pedagogical materials that function as a gateway to learning contemporary clarinet techniques and literature. Consequently, many clarinetists may be deterred from learning a significant portion of the repertoire from the past six decades, impeding their musical development. The purpose of this dissertation is to contribute to the pedagogical literature pertaining to extended clarinet techniques. The document consists of two main sections followed by two appendices. The first section (chapters 1-2) contains an introduction and a literature review of extant resources on extended clarinet techniques published between 1965–2020. This literature review forms the basis of the compendium of materials, found in Appendix A of this document, which aims to assist performers and teachers in searching for and selecting pedagogical materials involving extended clarinet techniques. -

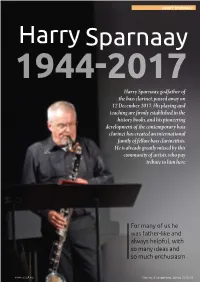

For Many of Us He Was Father-Like and Always Helpful, with So Many Ideas and So Much Enthusiasm

HARRY SPARNAAY Harry Sparnaay 1944-2017 Harry Sparnaay, godfather of the bass clarinet, passed away on 12 December 2017. His playing and teaching are firmly established in the history books, and his pioneering development of the contemporary bass clarinet has created an international family of fellow bass clarinettists. He is already greatly missed by this community of artists, who pay tribute to him here For many of us he was father-like and always helpful, with so many ideas and so much enthusiasm www.cassgb.org Clarinet & Saxophone, Spring 2018 13 HARRY SPARNAAY I think he said yes to everything, and assumed he’d figure out a way to do it, or a convincing way to fake it Oğuz Büyükberber Laura Carmichael (Netherlands/Turkey) (Netherlands) I moved to a new country in the midst Our dear Harry Sparnaay is gone from of my career at the age of 30, to study this world. What an important person with Harry after hearing him play a solo in my life. He was the reason I came to recital in Ostend. The things I learned The Netherlands in 1999, and studying from him go way beyond just the bass bass clarinet with him changed the clarinet. He keeps being a true inspiration course of my life in so many ways. His and a reminder for me when I feel lost or spirit, fortitude and knowledge will live disheartened. on in me and so many other people he At our first meeting, I asked Harry what touched. he thought about my visual impairment in The people he loved were like his relation to the conservatory curriculum. -

The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S

Vol. 47 • No. 2 March 2020 — 2020 ICA HONORARY MEMBERS — Ani Berberian Henri Bok Deborah Chodacki Paula Corley Philippe Cuper Stanley Drucker Larry Guy Francois Houle Seunghee Lee Andrea Levine Robert Spring Charles West Michael Lowenstern Anthony McGill Ricardo Morales Clarissa Osborn Felix Peikli Milan Rericha Jonathan Russell Andrew Simon Greg Tardy Annelien Van Wauwe Michele VonHaugg Steve Williamson Yuan Yuan YaoGuang Zhai Interview with Robert Spring | Rediscovering Ferdinand Rebay Part 3 A Tribute to the Hans Zinner Company | The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S. Howland Life Without Limits Our superb new series of Chedeville Clarinet mouthpieces are made in the USA to exacting standards from the finest material available. We are excited to now introduce the new ‘Chedeville Umbra’ and ‘Kaspar CB1’ Clarinet Barrels, the first products in our new line of high quality Clarinet Accessories. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] t is once again time for the membership to vote in the EDITORIAL BOARD biennial ICA election of officers. You will find complete Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, information about the slate of candidates and voting Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder instructions in this issue. As you may know, the ICA MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR bylaws were amended last summer to add the new position Gregory Barrett I [email protected] of International Vice President to the Executive Board. This position was added in recognition of the ICA initiative to AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR engage and cultivate more international membership and Kip Franklin [email protected] participation. -

Chronological Order

List of Works – Andys Skordis -In chronological order- 61 - “It’s a light blue day…” Music theatre based on “EIN HELLBLAUER TAG" by Ferdinard Von Schirach for Soprano, Mezzo Soprano, Bass, 3 Bass Trombones, Percussion, Tape Duration: ca. 35 minutes First performance: 13th May 2020, Elizabethkerk (DE) Performed by: Amelie Saaida, Derya Atakan, Ingo Witzke 61 - “Tri…Hita…Karana” For Contrabass Clarinet Duration: ca. 15 minutes First performance: ClarinetFest, April 2020, Manchester Commissioned and Performed by: Jason Alder Supported by Fonds Podium Kunsten 60 - “U…Zu” For Flute, Clarinet, Percussion, Piano, Violin, Viola, Violoncello Duration: ca. 13 minutes First performance: 9th November 2019, Opatija Tribune (HR) Commissioned and Performed by: Synchronos Ensemble 59 - “While the agitated beasts enter the garden of fear…” For Clarinet, Percussion, Piano, Violoncello Duration: ca. 45 minutes First performance: T.B.D Supported by Fonds Podium Kunsten 58 - “Crude Iron” Act I Music theatre on a novel by Sofronis Sofroniou For Narrator, voices and ensemble Duration: ca. 38 minutes First performance: 24th August 2019, Statonas - Ay. Lavrentis (GR) List of Works – Andys Skordis Commissioned and Performed by: International Festival Music Village 57 - “Lo…On” For Bass Baritone and Piano Duration: ca. 10 minutes First performance: 27th March 2019, Pallas theatre (CY) Commissioned and Performed by: Andrew Munn and Rami Sarieddine 56 - “Sisomo…Nitse” For 4 tambura Duration: ca. 6 minutes First performance: 2nd April 2019, Zagreb Bienale (HR) Commissioned and Performed by: Croatian academy of music 55 - “I…Zo” For Symphony orchestra a2 Duration: ca. 20 minutes First performance: Never Performed 54 - “In…Se - dawning-” Music theatre on a libretto by Jelena Vuksanovic For 4 roles, 3 Gamelan orchestras and Choir Duration: ca. -

Programme • Question-And-Answer Session - Tom Williams (Chair) with Sarah Watts and Composers (Siegel, Maccann, and Whitcombe)

Schedule Saturday 5 December, 10:00 am – 9:30 pm 10:00 am – 10:15 am: Welcome • Welcome and introduction from Elizabeth Kelly & Duncan MacLeod (NottFAR, University of Nottingham) – via MS Teams 10:15 am – 11:00 am: Presentations Session 1 • Jia Cao (Durham University) - Combining elements from the ancient Chinese and contemporary art music worlds: some critical reflections on the hybridizing of compositional methods, aesthetics and playing techniques (paper presentation) • Sue Newsome (Sydney Conservatorium, University of Sydney) - The Genesis of Yggdrasil – The World Tree – a Concerto for Contrabass Clarinet and Wind Symphony by Cameron Lam (Demonstration) 11:00 am – 11:30 am: Presentations Session 1 Q&A • Question-and-answer session - Harriet Boyd-Bennett (chair) with Jia Cao and Sue Newsome 11:30 am – 12:30 pm: Presentations Session 2 • Bofan Ma (RNCM) - In Search of the in-between, and an embodied compositional practice (Paper Presentation) • Alfia Nakipbekova (University of Leeds) – Reading Khlebnikov for cello and tape (Demonstration) 12:30 pm – 1:00 pm: Presentations Session 2 Q&A • Question-and-answer session – Edmund Hunt (chair) with Bofan Ma and Alfia Nakipbekova 1:00 pm – 2:00 pm: Opening Concert • Sarah Watts (Sheffield University) & SCAW Duo perform: Memoriale II, Annachiara Gedda; Salamander, Wayne Siegel; Undulating Depths, Thomas Whitcombe; Leaks and Spills, Chris MacCann 2:00 pm – 2:30 pm: Opening Concert Q&A Symposium Programme • Question-and-answer session - Tom Williams (chair) with Sarah Watts and composers (Siegel, -

Compositions for Frederick Thurston | Ivory Clarinets Also in This Issue

Vol. 46 • No. 2 March 2019 Compositions for Frederick Thurston | Ivory Clarinets Also in this issue... Interview with Benjamin Lulich | Croatian Clarinet Concertos D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. The President’s EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] hope that 2019 is a rewarding year for everyone in the worldwide clarinet community! The ICA starts off the year EDITORIAL BOARD with much to celebrate – a healthy financial outlook, striking Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, new logo, and great excitement about ClarinetFest® 2019 in Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder Knoxville and ClarinetFest® 2020 in Reno/Lake Tahoe. I MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR Speaking of Knoxville, ClarinetFest® 2019 is rapidly approaching! The Knoxville artistic team led by Vic Chavez is doing a fantastic job Gregory Barrett of preparing for the festival. They have engaged a spectacular roster [email protected] of headline artists, including Mariam Adam, William and Catherine AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR Hudgins, Sylvie Hue, Bil Jackson, Kathy Jones, Ricardo Morales, Chris Nichols Mark Nuccio, Ken Peplowski, Milan Rericha, Anton Rist, Gabor [email protected] Mitchell Estrin Varga, and clarinet legend Stanley Drucker. We will welcome soloists from the United States military bands, and rising young artists Han GRAPHIC DESIGN Kim, winner of the 2016 Jacques Lancelot International Clarinet Competition, and Pablo Tirado Karry Thomas Graphic Design Villaescusa, winner of the 2018 ICA Young Artist Competition. ICA Honorary Memberships will [email protected] be awarded to three clarinet luminaries: Ron Odrich, Alan Stanek and Eddy Vanoosthuyse. -

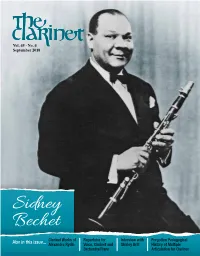

Sidney Bechet Clarinet Works of Repertoire for Interview with Forgotten Pedagogical Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 4 September 2018 Sidney Bechet Clarinet Works of Repertoire for Interview with Forgotten Pedagogical Also in this issue... Alexandre Rydin Voice, Clarinet and Shirley Brill History of Multiple Orchestra/Piano Articulation for Clarinet D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear Members and Jessica Harrie Friends of the International Clarinet Association: [email protected] s I write this message just days after the conclusion of EDITORIAL BOARD ClarinetFest® 2018, I continue to marvel at the fantastic Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, festival held on the beautiful Belgian coast of Ostend. We Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder are grateful to our friends Eddy Vanoosthuyse, artistic Adirector of ClarinetFest® 2018, and the Ostend team and family of MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR the late Guido Six – Chantal Six Vandekerckhove, Bert Six and Gaby Gregory Barrett – [email protected] Six – who together organized a truly extraordinary and memorable festival featuring artists from over 55 countries. AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR The first day alone contained an amazing array of concerts Chris Nichols – [email protected] including an homage to the legendary Guido Six by the Claribel Clarinet Choir, followed by the Honorary Member concert featuring Caroline Hartig GRAPHIC DESIGN Karl Leister, Luis Rossi, Antonio Saiote and the newest ICA honorary Karry Thomas Graphic Design member inductee, Charles Neidich. Later that evening was the [email protected] world premiere of the Piovani Clarinet Concerto with the Brussels Philharmonic, performed by Artistic Director Eddy Vanoosthuyse. -

FLOWERS WITHOUT BORDERS July 9-11, 16-18, 23-25, 30-31 Enter to Win a Vocalise Mouthpiece Scan the Code and Complete Your Entry

FLOWERS WITHOUT BORDERS July 9-11, 16-18, 23-25, 30-31 Enter to Win a Vocalise Mouthpiece Scan the code and complete your entry. backunmusical.com gives a soul to theMusic universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, and charm and gaiety to life and to everything. ~Plato Now, more than ever, E DWIN • HUD RE EIGAN SO • • W D N H R • T • C E R D I D IP i V Y I L E N P U S S IT T I A S play on! • S N I L R A E Meet Some I K W B • I A K S T • E L Players D A L G A E N R O R D We Love! O c a B M • B • U E L S N F O I V A D A • Z M H E Patents. See website. www.rovnerproducts.com Established 2013 Heather Rodriguez Alcides Rodriguez RMS offers a premium selection of Hand selected Buffet clarinets clarinets for the demanding artist, and accessories educator and student. Artist level set ups, upgrades, repair work and overhauls www.rodriguezmusical.com 470-545-9803 [email protected] A NEW SPECIES OF REED VENN signals the dawn of a new era in woodwinds innovation: combining the stability and longevity of a synthetic reed with the sound and feel of natural cane. To mimic the organic structure of cane, we reverse-engineered cane itself, layering di erent strengths of polymer fi bers with resin and organic reed elements to make up the reed blank. -

Clarinetfest 2019 Working Program

Wednesday, July 24, 2019 Program Wednesday, July 24, 2019 8:00 AM – 5:00 PM Student Union Lobby Registration 1:00 PM James R. Cox Auditorium - Alumni Memorial Building Gala Opening Recital Viktor’s Lament from The Terminal John Williams (b.1932) I Fall in Love Too Easily Jule Styne/Sammy Kahn (1905-1994)/(1913-1993) Knoxville ’19 Ron Odrich Ron Odrich, clarinet Sean Claire, violin Audrey Price, violin Sherri Fleshner, viola D. Scot Williams, cello Jeffrey Whaley, horn Mark Boling, guitar Gary Mazzaroppi, bass Ron Odrich’s appearance is sponsored in part by Backun Musical Services Première rhapsodie Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Pablo Tirado, clarinet (Winner, 2018 ICA Young Artist Competition) Samuel Tirado Villaescusa, piano Elegy & Tango Dirk Brossé (b.1960) Eddy Vanoosthuyse, clarinet Esther Park, piano Eddy Vanoosthuyse’s appearance is sponsored in part by Buffet Crampon and Vandoren Wednesday, July 24, 2019 Sonate in B Paul Hindemith I. Mäßig bewegt (1895-1963) II. Lebhaft III. Sehr langsam IV. Kleines Rondo, gemächlich Stanley Drucker, clarinet Esther Jung, piano Stanley Drucker’s appearance is sponsored in part by Buffet Crampon and Vandoren 2:00 – 3:30 PM Powell Recital Hall - School of Music ICA Research Competition – Session 1 Michael Gersten (USA) Modern Interpretation of Ornamentation in Naftule Brandwein’s Firn di Mekhutonim Aheym and Der Heyser Bulgar Austin McFarland (USA) The Forgotten Works of Ivana Loudová: A Post-World War II Composer and Her Gifts to the Clarinet Repertoire Bryce Newcomer (USA) Performer as Composer: A Guide to the Clarinet Eingänge in Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto K. 622 ICA Research Competition Semi-Final Round Judges Sarah Watts, Sheffield University, Royal Northern College of Music Timothy Phillips.