Introducing Extended Techniques and Contemporary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration Into the Modern Clarinet Studio

UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones 5-1-2015 The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio Jennifer Beth Iles University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Music Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Iles, Jennifer Beth, "The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio" (2015). UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones. Paper 2367. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Scholarship@UNLV. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses/ Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE BASS CLARINET: SUPPORT FOR ITS INTEGRATION INTO THE MODERN CLARINET STUDIO By Jennifer Beth Iles Bachelor of Music Education McNeese State University 2005 Master of Music Performance University of North Texas 2008 A doctoral document submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada Las Vegas May 2015 We recommend the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Jennifer Iles entitled The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music Marina Sturm, D.M.A., Committee Chair Cheryl Taranto, Ph.D., Committee Member Stephen Caplan, D.M.A., Committee Member Ken Hanlon, D.M.A., Committee Chair Margot Mink Colbert, B.S., Graduate College Representative Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D., Interim Dean of the Graduate College May 2015 ii ABSTRACT The bass clarinet of the twenty-first century has come into its own. -

EPARM Conference 2020 16-18 April, Royal Academy of Music, London

European Platform for Artistic Research in Music EPARM Conference 2020 16-18 April, Royal Academy of Music, London PROGRAMME Thursday, 16th April Time Activity Location REGISTRATION 13.30 Informal Networking – Coffee available 14:30 – 15:30 Guided Tour of the Academy Opening Event Music Introduction Official Welcome by: 15:45 – 16.30 - Jonathan Freeman-Attwood, Principal of the Royal Dukes Hall Academy of Music - Stefan Gies, CEO of the AEC - Stephen Broad, EPARM Chair Plenary Session I – Keynote by Timothy Jones 16.30 – 17.30 Dukes Hall Moderated by David Gorton 17.30 –18:00 Networking with Refreshments 18:00 – 19:00 Concert 19:00 – 20:00 Reception L8 NITE Performance I A Concert Room Ghost Trance Solo’s: a solo interpretation of Anthony Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music, Kobe Van Cauwenberghe, Royal Conservatoire, Antwerp, Belgium 20:00 – 20:30 L8 NITE Performance I B David Josefowitz Recital Hall Fantasía quasi Sonata: an “in-version” of Beethoven’s Op. 27 No. 2, Luca Chiantore, ESMUC - Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya), Barcelona, Spain L8 NITE Performances I C Angela Burgess Recital Hall LEMUR: Collective Artistic Research within an Ensemble, Francis Michael Duch, NTNU – Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway 20:30 – 20:45 Break to allow room change L8 NITE Performances II A Concert Room Ensemble 1604 presents ...shadows that in darkness dwell…, Timothy Cooper, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Glasgow, UK 20:45 – 21:15 L8 NITE Performances II B David Josefowitz Recital Hall Love at first sound: engaging -

Dissertation 3.19.2021

Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Timothy Salzman, Chair David Rahbee Benjamin Lulich Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music © Copyright 2021 Caitlin Beare University of Washington Abstract Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Timothy Salzman School of Music The exploration and implementation of new timbral possibilities and techniques over the past century have redefined approaches to clarinet performance and pedagogy. As the body of repertoire involving nontraditional, or “extended,” clarinet techniques has grown, so too has the pedagogical literature on contemporary clarinet performance, yielding method books, dissertations, articles, and online resources. Despite the wealth of resources on extended clarinet techniques, however, few authors offer accessible pedagogical materials that function as a gateway to learning contemporary clarinet techniques and literature. Consequently, many clarinetists may be deterred from learning a significant portion of the repertoire from the past six decades, impeding their musical development. The purpose of this dissertation is to contribute to the pedagogical literature pertaining to extended clarinet techniques. The document consists of two main sections followed by two appendices. The first section (chapters 1-2) contains an introduction and a literature review of extant resources on extended clarinet techniques published between 1965–2020. This literature review forms the basis of the compendium of materials, found in Appendix A of this document, which aims to assist performers and teachers in searching for and selecting pedagogical materials involving extended clarinet techniques. -

Van Cott Information Services (Incorporated 1990) Offers Books

Clarinet Catalog 9a Van Cott Information Services, Inc. 02/08/08 presents Member: Clarinet Books, Music, CDs and More! International Clarinet Association This catalog includes clarinet books, CDs, videos, Music Minus One and other play-along CDs, woodwind books, and general music books. We are happy to accept Purchase Orders from University Music Departments, Libraries and Bookstores (see Ordering Informa- tion). We also have a full line of flute, saxophone, oboe, and bassoon books, videos and CDs. You may order online, by fax, or phone. To order or for the latest information visit our web site at http://www.vcisinc.com. Bindings: HB: Hard Bound, PB: Perfect Bound (paperback with square spine), SS: Saddle Stitch (paper, folded and stapled), SB: Spiral Bound (plastic or metal). Shipping: Heavy item, US Media Mail shipping charges based on weight. Free US Media Mail shipping if ordered with another item. Price and availability subject to change. C001. Altissimo Register: A Partial Approach by Paul Drushler. SHALL-u-mo Publications, SB, 30 pages. The au- Table of Contents thor's premise is that the best choices for specific fingerings Clarinet Books ....................................................................... 1 for certain passages can usually be determined with know- Single Reed Books and Videos................................................ 6 ledge of partials. Diagrams and comments on altissimo finger- ings using the fifth partial and above. Clarinet Music ....................................................................... 6 Excerpts and Parts ........................................................ 6 14.95 Master Classes .............................................................. 8 C058. The Art of Clarinet Playing by Keith Stein. Summy- Birchard, PB, 80 pages. A highly regarded introduction to the Methods ........................................................................ 8 technical aspects of clarinet playing. Subjects covered include Music ......................................................................... -

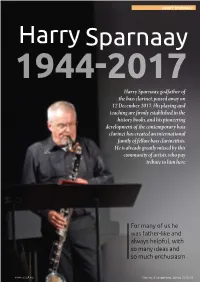

For Many of Us He Was Father-Like and Always Helpful, with So Many Ideas and So Much Enthusiasm

HARRY SPARNAAY Harry Sparnaay 1944-2017 Harry Sparnaay, godfather of the bass clarinet, passed away on 12 December 2017. His playing and teaching are firmly established in the history books, and his pioneering development of the contemporary bass clarinet has created an international family of fellow bass clarinettists. He is already greatly missed by this community of artists, who pay tribute to him here For many of us he was father-like and always helpful, with so many ideas and so much enthusiasm www.cassgb.org Clarinet & Saxophone, Spring 2018 13 HARRY SPARNAAY I think he said yes to everything, and assumed he’d figure out a way to do it, or a convincing way to fake it Oğuz Büyükberber Laura Carmichael (Netherlands/Turkey) (Netherlands) I moved to a new country in the midst Our dear Harry Sparnaay is gone from of my career at the age of 30, to study this world. What an important person with Harry after hearing him play a solo in my life. He was the reason I came to recital in Ostend. The things I learned The Netherlands in 1999, and studying from him go way beyond just the bass bass clarinet with him changed the clarinet. He keeps being a true inspiration course of my life in so many ways. His and a reminder for me when I feel lost or spirit, fortitude and knowledge will live disheartened. on in me and so many other people he At our first meeting, I asked Harry what touched. he thought about my visual impairment in The people he loved were like his relation to the conservatory curriculum. -

Instructions for Authors

Journal of Science and Arts Supplement at No. 2(13), pp. 157-161, 2010 THE CLARINET IN THE CHAMBER MUSIC OF THE 20TH CENTURY FELIX CONSTANTIN GOLDBACH Valahia University of Targoviste, Faculty of Science and Arts, Arts Department, 130024, Targoviste, Romania Abstract. The beginning of the 20th century lay under the sign of the economic crises, caused by the great World Wars. Along with them came state reorganizations and political divisions. The most cruel realism, of the unimaginable disasters, culminating with the nuclear bombs, replaced, to a significant extent, the European romanticism and affected the cultural environment, modifying viewpoints, ideals, spiritual and philosophical values, artistic domains. The art of the sounds developed, being supported as well by the multiple possibilities of recording and world distribution, generated by the inventions of this epoch, an excessively technical one, the most important ones being the cinema, the radio, the television and the recordings – electronic or on tape – of the creations and interpretations. Keywords: chamber music of the 20th century, musical styles, cultural tradition. 1. INTRODUCTION Despite all the vicissitudes, music continued to ennoble the human souls. The study of the instruments’ construction features, of the concert halls, the investigation of the sound and the quality of the recordings supported the formation of a series of high-quality performers and the attainment of high performance levels. The international contests organized on instruments led to a selection of the values of the interpretative art. So, the exceptional professional players are no longer rarities. 2. DISCUSSIONS The economic development of the United States of America after the two World Wars, the cultural continuity in countries with tradition, such as England and France, the fast restoration of the West European states, including Germany, represented conditions that allowed the flourishing of musical education. -

The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S

Vol. 47 • No. 2 March 2020 — 2020 ICA HONORARY MEMBERS — Ani Berberian Henri Bok Deborah Chodacki Paula Corley Philippe Cuper Stanley Drucker Larry Guy Francois Houle Seunghee Lee Andrea Levine Robert Spring Charles West Michael Lowenstern Anthony McGill Ricardo Morales Clarissa Osborn Felix Peikli Milan Rericha Jonathan Russell Andrew Simon Greg Tardy Annelien Van Wauwe Michele VonHaugg Steve Williamson Yuan Yuan YaoGuang Zhai Interview with Robert Spring | Rediscovering Ferdinand Rebay Part 3 A Tribute to the Hans Zinner Company | The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S. Howland Life Without Limits Our superb new series of Chedeville Clarinet mouthpieces are made in the USA to exacting standards from the finest material available. We are excited to now introduce the new ‘Chedeville Umbra’ and ‘Kaspar CB1’ Clarinet Barrels, the first products in our new line of high quality Clarinet Accessories. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] t is once again time for the membership to vote in the EDITORIAL BOARD biennial ICA election of officers. You will find complete Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, information about the slate of candidates and voting Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder instructions in this issue. As you may know, the ICA MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR bylaws were amended last summer to add the new position Gregory Barrett I [email protected] of International Vice President to the Executive Board. This position was added in recognition of the ICA initiative to AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR engage and cultivate more international membership and Kip Franklin [email protected] participation. -

Závěrečné Práce

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Hudební fakulta Katedra dechových nástrojů Hra na klarinet Umělec pedagog Charles Neidich a jeho vliv na vývoj americké klarinetové školy Diplomová práce Autor práce: Jakub Hrdlička Vedoucí práce: doc. Milan Polák Oponent práce: doc. Vít Spilka Brno 2015 Bibliografický záznam HRDLIČKA, Jakub. Umělec a pedagog Charles Neidich a jeho vliv na vývoj americké klarinetové školy [Artist educator Charles Neidich and his influence on the American Clarinet school] Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hudební fakulta, Katedra dechových nástrojů, 2015 doc. Milan Polák s. [69] Anotace Diplomová práce Umělec a pedagog Charles Neidich a jeho vliv na vývoj americké klarinetové školy pojednává o osobnosti Charlese Neidicha. Práce je rozdělena do několika částí, ve kterých se zaměřuji na americkou klarinetovou školu, Ch. N. jako umělce a pedagoga a v další fázi analýzu a popis jeho metodiky a rozhovor s nejúspěšnějšími žáky. Annotation Diploma thesis „Artist educator Charles Neidich and his influence on the American Clarinet school” deals with personality of Charles Neidich. The work is divided into several sections in which I focus on American Clarinet school, Ch. N. as an artist and educator and in the next phase analyze and description of his pedagogical methods and interview with the most renowned students. Klíčová slova Americká klarinetová škola, Charles Neidich, umělec, pedagog Keywords American clarinet school, Charles Neidich, artist, educator Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem předkládanou práci zpracoval samostatně a použil jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. Jakub Hrdlička V Brně dne 14. 8. 2015 Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád poděkoval docentu Milanu Polákovi za laskavou spolupráci při tvorbě této práce a také umělcům Mate Bekavac, Sharon Kam, Kari Kriikku za poskytnutí rozhovorů. -

Van Cott Information Services, Inc. Presents Woodwind Books, Music

Member: Van Cott Information Services, Inc. International Clarinet presents Association Woodwind Books, Music, CDs and More! This is our complete woodwind price list. Ask for the catalog for your area of interest or visit our web site at http://www.vcisinc.com for a complete description of all our products and downloadable catalogs. We accept orders by phone, fax, and the internet. Price List dated 4/01/20 – Price and Availability Subject to Change B115. Concerto for Bassoon & Orch (Pn Reduc) (Mancusi) ................... 19.95 Bassoon B112. Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra in B-flat (PR) (JC Bach) ....... 17.95 B103. 2 Duos Concertants Op. 65 for 2 Bassoons (Fuchs) ...................... 18.50 B113. Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra in E-flat (PR) (JC Bach) ......... 6.95 B098. 6 Sonates Op. 40 Vol. 1 for 2 Bassoons (Bodin de Boismortier) ..... 13.95 B118. Concerto for Bassoon & Orch Op. 75 (PR) (Weber/Waterhouse) .. 23.95 B099. 6 Sonates Op. 40 Vol. 2 for 2 Bassoons (Bodin de Boismortier) ..... 13.95 B170. Concerto for Contrabassoon Piano Reduction (Dorff) .................. 16.95 B100. 6 Sonates Vol. 1 for 2 Bassoons (Braun) ........................................ 10.95 B148. Concerto in F major Op. 75 for Bassoon & Pn (Weber/Sharrow) .. 14.75 B101. 6 Sonates Vol. 2 for 2 Bassoons (Braun) ........................................ 13.95 B147. Concerto for F Major for Bassoon and Piano (Hummel) .............. 14.95 B166. 8 More Original Jazz Duos for Clarinet and Bassoon (Curtis) ....... 14.50 B035. Concerto for Bassoon and Wind Ens. (bs & piano ed.) (Ewazen) .. 24.95 B128. 10 (Ten) Etudes for Bassoon (Lowman) .......................................... 4.00 B132. -

The Comprehensive Pedagogical Approach to Clarinet of D

THE COMPREHENSIVE PEDAGOGICAL APPROACH TO CLARINET OF D. RAY MCCLELLAN By AMANDY BANDEIRA DE ARAÚJO (Under the Direction of D. Ray McClellan) ABSTRACT This document is a case study of Dr. D. Ray McClellan’s clarinet teaching. His distinctive pedagogy relies on a comprehensive approach towards clarinet playing. Different aspects of his teaching are explored, starting with a description of his background in music, followed by a presentation of his concepts about clarinet techniques, warm-ups, practice techniques, and musicianship. The data collected for this research came from interviews and observation of lessons. I also compare Dr. McClellan’s approach with other professors’ pedagogy and concepts of clarinet playing. The warm-ups are a fundamental part of Dr. McClellan’s approach, and the document includes a compendium with most of Dr. McClellan’s warm-up exercises. My goal was to create a document that is a source of valuable information about clarinet techniques and clarinet teaching. INDEX WORDS: Clarinet pedagogy, Clarinet performance, Practice techniques, Clarinet warm-ups, Music interpretation. THE CLARINET TEACHING OF D. RAY MCCLELLAN By AMANDY BANDEIRA DE ARAÚJO B. Mus., Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil, 2004 M.M. University of South Carolina, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Amandy Bandeira de Araújo All Rights Reserved The Clarinet Teaching of D. Ray McClellan By Amandy Bandeira de Araújo Major Professor: D. Ray McClellan Committee: Reid G. Messich David Haas Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 Acknowledgements To all my family (uncles, aunts, and cousins) who always supported my dreams, especially to my mother Ana, my father Gildásio, and my sister Amanara. -

Chronological Order

List of Works – Andys Skordis -In chronological order- 61 - “It’s a light blue day…” Music theatre based on “EIN HELLBLAUER TAG" by Ferdinard Von Schirach for Soprano, Mezzo Soprano, Bass, 3 Bass Trombones, Percussion, Tape Duration: ca. 35 minutes First performance: 13th May 2020, Elizabethkerk (DE) Performed by: Amelie Saaida, Derya Atakan, Ingo Witzke 61 - “Tri…Hita…Karana” For Contrabass Clarinet Duration: ca. 15 minutes First performance: ClarinetFest, April 2020, Manchester Commissioned and Performed by: Jason Alder Supported by Fonds Podium Kunsten 60 - “U…Zu” For Flute, Clarinet, Percussion, Piano, Violin, Viola, Violoncello Duration: ca. 13 minutes First performance: 9th November 2019, Opatija Tribune (HR) Commissioned and Performed by: Synchronos Ensemble 59 - “While the agitated beasts enter the garden of fear…” For Clarinet, Percussion, Piano, Violoncello Duration: ca. 45 minutes First performance: T.B.D Supported by Fonds Podium Kunsten 58 - “Crude Iron” Act I Music theatre on a novel by Sofronis Sofroniou For Narrator, voices and ensemble Duration: ca. 38 minutes First performance: 24th August 2019, Statonas - Ay. Lavrentis (GR) List of Works – Andys Skordis Commissioned and Performed by: International Festival Music Village 57 - “Lo…On” For Bass Baritone and Piano Duration: ca. 10 minutes First performance: 27th March 2019, Pallas theatre (CY) Commissioned and Performed by: Andrew Munn and Rami Sarieddine 56 - “Sisomo…Nitse” For 4 tambura Duration: ca. 6 minutes First performance: 2nd April 2019, Zagreb Bienale (HR) Commissioned and Performed by: Croatian academy of music 55 - “I…Zo” For Symphony orchestra a2 Duration: ca. 20 minutes First performance: Never Performed 54 - “In…Se - dawning-” Music theatre on a libretto by Jelena Vuksanovic For 4 roles, 3 Gamelan orchestras and Choir Duration: ca.