Developing Interactive Electronic Systems for Improvised Music-Justified

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

Interaction and Cognition in the Orchestra

Situated, embodied, distributed: interaction and cognition in the orchestra Katharine Louise Nancy Parton Submitted in total fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Abstract The orchestral ensemble exists as a group of people who come together to prepare for public performance of music and has done so for several hundred years. In this thesis I examine the interactions which occur during this process in a current day professional orchestra. My focus is on analysing how members of the orchestra, the orchestral organisation and the conductor use their bodies, artefacts, time and space. My approach to examining these behaviours is informed by social interaction methodologies and theories of distributed cognition. Chapter 5 presents an ethnographic account of the construction of space and delineation of time for rehearsal. I examine how the City Symphony Orchestra (CSO) and their management use both space and time to prioritise and privilege the work of the orchestra. Chapter 6 focuses on conductor gestures and I use this analysis to argue that the gestures are complex with components occurring simultaneously as well as sequentially. I argue that conductor gesture creates its own context as it is deployed interactionally and is deeply embedded within social and cultural context. I use the theory of composite utterances to demonstrate that conductor gesture is more than a simple single sign per semantic unit. Chapter 7 considers how orchestral musicians organise their cognition within the physical and social environment of the rehearsal. I show that orchestral musicians distribute their cognition across their bodies, other interactants and culturally constructed artefacts. -

The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration Into the Modern Clarinet Studio

UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones 5-1-2015 The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio Jennifer Beth Iles University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Music Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Iles, Jennifer Beth, "The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio" (2015). UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones. Paper 2367. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Scholarship@UNLV. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses/ Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE BASS CLARINET: SUPPORT FOR ITS INTEGRATION INTO THE MODERN CLARINET STUDIO By Jennifer Beth Iles Bachelor of Music Education McNeese State University 2005 Master of Music Performance University of North Texas 2008 A doctoral document submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada Las Vegas May 2015 We recommend the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Jennifer Iles entitled The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music Marina Sturm, D.M.A., Committee Chair Cheryl Taranto, Ph.D., Committee Member Stephen Caplan, D.M.A., Committee Member Ken Hanlon, D.M.A., Committee Chair Margot Mink Colbert, B.S., Graduate College Representative Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D., Interim Dean of the Graduate College May 2015 ii ABSTRACT The bass clarinet of the twenty-first century has come into its own. -

EPARM Conference 2020 16-18 April, Royal Academy of Music, London

European Platform for Artistic Research in Music EPARM Conference 2020 16-18 April, Royal Academy of Music, London PROGRAMME Thursday, 16th April Time Activity Location REGISTRATION 13.30 Informal Networking – Coffee available 14:30 – 15:30 Guided Tour of the Academy Opening Event Music Introduction Official Welcome by: 15:45 – 16.30 - Jonathan Freeman-Attwood, Principal of the Royal Dukes Hall Academy of Music - Stefan Gies, CEO of the AEC - Stephen Broad, EPARM Chair Plenary Session I – Keynote by Timothy Jones 16.30 – 17.30 Dukes Hall Moderated by David Gorton 17.30 –18:00 Networking with Refreshments 18:00 – 19:00 Concert 19:00 – 20:00 Reception L8 NITE Performance I A Concert Room Ghost Trance Solo’s: a solo interpretation of Anthony Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music, Kobe Van Cauwenberghe, Royal Conservatoire, Antwerp, Belgium 20:00 – 20:30 L8 NITE Performance I B David Josefowitz Recital Hall Fantasía quasi Sonata: an “in-version” of Beethoven’s Op. 27 No. 2, Luca Chiantore, ESMUC - Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya), Barcelona, Spain L8 NITE Performances I C Angela Burgess Recital Hall LEMUR: Collective Artistic Research within an Ensemble, Francis Michael Duch, NTNU – Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway 20:30 – 20:45 Break to allow room change L8 NITE Performances II A Concert Room Ensemble 1604 presents ...shadows that in darkness dwell…, Timothy Cooper, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Glasgow, UK 20:45 – 21:15 L8 NITE Performances II B David Josefowitz Recital Hall Love at first sound: engaging -

Dissertation 3.19.2021

Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Timothy Salzman, Chair David Rahbee Benjamin Lulich Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music © Copyright 2021 Caitlin Beare University of Washington Abstract Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Timothy Salzman School of Music The exploration and implementation of new timbral possibilities and techniques over the past century have redefined approaches to clarinet performance and pedagogy. As the body of repertoire involving nontraditional, or “extended,” clarinet techniques has grown, so too has the pedagogical literature on contemporary clarinet performance, yielding method books, dissertations, articles, and online resources. Despite the wealth of resources on extended clarinet techniques, however, few authors offer accessible pedagogical materials that function as a gateway to learning contemporary clarinet techniques and literature. Consequently, many clarinetists may be deterred from learning a significant portion of the repertoire from the past six decades, impeding their musical development. The purpose of this dissertation is to contribute to the pedagogical literature pertaining to extended clarinet techniques. The document consists of two main sections followed by two appendices. The first section (chapters 1-2) contains an introduction and a literature review of extant resources on extended clarinet techniques published between 1965–2020. This literature review forms the basis of the compendium of materials, found in Appendix A of this document, which aims to assist performers and teachers in searching for and selecting pedagogical materials involving extended clarinet techniques. -

French Musical Broadcasting in 1939 Through a Comparison Between Radio-Paris and Radio-Cité Christophe Bennet

French Musical Broadcasting in 1939 through a Comparison between Radio-Paris and Radio-Cité Christophe Bennet To cite this version: Christophe Bennet. French Musical Broadcasting in 1939 through a Comparison between Radio-Paris and Radio-Cité. 2015. hal-01146878 HAL Id: hal-01146878 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01146878 Submitted on 6 May 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. French Musical Broadcasting in 1939 – PLM – Christophe Bennet – May 2014 FRENCH MUSICAL BROADCASTING IN 1939 THROUGH A COMPARISON BETWEEN RADIO-PARIS AND RADIO-CITÉ by Christophe BENNET THE year 1939 leads us to conclude the annual panorama of the French musical broadcasting of the thirties, a panorama organized through the prism of two big stations of the public and private networks. We have seen that in 1938, while the influence of the Government was weighing even more on the public stations (without any improvement of the programs), the commercial stations, strengthened by several years of experience, were adapting their program schedules in accordance with the success of their new formulas. By responding to the expectations of their audience, those stations continue their action in 1939. -

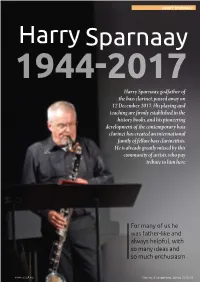

For Many of Us He Was Father-Like and Always Helpful, with So Many Ideas and So Much Enthusiasm

HARRY SPARNAAY Harry Sparnaay 1944-2017 Harry Sparnaay, godfather of the bass clarinet, passed away on 12 December 2017. His playing and teaching are firmly established in the history books, and his pioneering development of the contemporary bass clarinet has created an international family of fellow bass clarinettists. He is already greatly missed by this community of artists, who pay tribute to him here For many of us he was father-like and always helpful, with so many ideas and so much enthusiasm www.cassgb.org Clarinet & Saxophone, Spring 2018 13 HARRY SPARNAAY I think he said yes to everything, and assumed he’d figure out a way to do it, or a convincing way to fake it Oğuz Büyükberber Laura Carmichael (Netherlands/Turkey) (Netherlands) I moved to a new country in the midst Our dear Harry Sparnaay is gone from of my career at the age of 30, to study this world. What an important person with Harry after hearing him play a solo in my life. He was the reason I came to recital in Ostend. The things I learned The Netherlands in 1999, and studying from him go way beyond just the bass bass clarinet with him changed the clarinet. He keeps being a true inspiration course of my life in so many ways. His and a reminder for me when I feel lost or spirit, fortitude and knowledge will live disheartened. on in me and so many other people he At our first meeting, I asked Harry what touched. he thought about my visual impairment in The people he loved were like his relation to the conservatory curriculum. -

Interpreting Musical Structure Through Choreography in Gershwin's

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-23-2019 Music in Motion: Interpreting Musical Structure through Choreography in Gershwin’s "An American in Paris" Spencer Reese University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Reese, Spencer, "Music in Motion: Interpreting Musical Structure through Choreography in Gershwin’s "An American in Paris"" (2019). Doctoral Dissertations. 2172. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/2172 Abstract Music in Motion Interpreting Musical Structure through Choreography in Gershwin’s An American in Paris Spencer Matthew Reese, D.M.A. University of Connecticut, 2019 This dissertation explores the relationship between the theoretic interpretation of music (through analysis of a score) and the kinesthetic interpretation of it (through dance). While compelling choreography often evokes the same expressive qualities as a score, music and dance each have expressive and structural components. This study looks beyond expressive unity to examine how formal elements of a musical score are embodied in a choreographic interpretation of it. George Gershwin’s now-iconic symphonic poem An American in Paris, while conceived as concert music, was almost immediately interpreted in dance onstage. It also inspired larger narrative works, including a film choreographed by Gene Kelly and a musical helmed by Christopher Wheeldon. When a score is written for dance, the logistical considerations of choreography likely influence the piece’s composition. But in the case of Paris, the structural details of the music itself have consistently given artists the impression that it is danceable. Gershwin’s life and musical style are examined, including his synthesis of popular and Western art music. -

The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S

Vol. 47 • No. 2 March 2020 — 2020 ICA HONORARY MEMBERS — Ani Berberian Henri Bok Deborah Chodacki Paula Corley Philippe Cuper Stanley Drucker Larry Guy Francois Houle Seunghee Lee Andrea Levine Robert Spring Charles West Michael Lowenstern Anthony McGill Ricardo Morales Clarissa Osborn Felix Peikli Milan Rericha Jonathan Russell Andrew Simon Greg Tardy Annelien Van Wauwe Michele VonHaugg Steve Williamson Yuan Yuan YaoGuang Zhai Interview with Robert Spring | Rediscovering Ferdinand Rebay Part 3 A Tribute to the Hans Zinner Company | The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S. Howland Life Without Limits Our superb new series of Chedeville Clarinet mouthpieces are made in the USA to exacting standards from the finest material available. We are excited to now introduce the new ‘Chedeville Umbra’ and ‘Kaspar CB1’ Clarinet Barrels, the first products in our new line of high quality Clarinet Accessories. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] t is once again time for the membership to vote in the EDITORIAL BOARD biennial ICA election of officers. You will find complete Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, information about the slate of candidates and voting Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder instructions in this issue. As you may know, the ICA MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR bylaws were amended last summer to add the new position Gregory Barrett I [email protected] of International Vice President to the Executive Board. This position was added in recognition of the ICA initiative to AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR engage and cultivate more international membership and Kip Franklin [email protected] participation. -

Musical Washing Machines, Composer-Performers, and Other Blurring Boundaries: How Women Make a Difference in Electroacoustic Music Hannah Bosma

Document generated on 09/25/2021 8:20 a.m. Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique Musical Washing Machines, Composer-Performers, and Other Blurring Boundaries: How Women Make a Difference in Electroacoustic Music Hannah Bosma In and Out of the Sound Studio Article abstract Volume 26, Number 2, 2006 This essay explores the possibilities and limitations of an écriture féminine musicale in electroacoustic music. Theories by Cox, Dame, and Citron about URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013229ar "women's music" are discussed alongside research on women electroacoustic DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1013229ar composers by McCartney and Hinkle-Turner, and analyses of works by Rudow, Isadora, and LaBerge. The operation of gendered musical categories is See table of contents analysed in the appropriation of Cathy Berberian's "voice" by Berio. Strategies for destabilizing historically gendered categories in music are discussed, including feminine/feminist content, composer-performers, interdisciplinarity, and collaboration. The interdisciplinary character of many women's work may Publisher(s) hamper its documentation and thus its survival. The author's research at Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités NEAR/Donemus focuses on this problem. canadiennes ISSN 1911-0146 (print) 1918-512X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Bosma, H. (2006). Musical Washing Machines, Composer-Performers, and Other Blurring Boundaries: How Women Make a Difference in Electroacoustic Music. Intersections, 26(2), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013229ar Copyright © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit universités canadiennes, 2007 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra JEAN MARTINON, Conductor

1967 Eighty-ninth Season 1968 UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Charles A. Sink, President Gail W. Rector, Executive Director Lester McCoy, Conductor First Concert Eighty-ninth Annual Choral Union Series Complete Series 3585 Forty-first program in the Sesquicentennial Year of The University of Michigan Chicago Symphony Orchestra JEAN MARTINON, Conductor SUNDAY AFTERNOON, OCTOBER 1, 1967, AT 2:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM "Ciaconna" .. BUXTEHUDE-CHAVEZ Concerto for Trumpet in D major TELEMANN Adagio Allegro Grave Allegro ADoLPH HmsETlI, Trumpet Symphony No.7 (world premiere) ROGER SESSIONS (Commissioned by The University of Michigan for its Sesquicentennial Year) Allegro con fuoco Lento e dolce Allegro misurato-Tempo 1, ma impetuoso; Epilogue: Largo INTERMISSION Suite, N obilissima visione HINDEMITH Introduction and Rondo March and Pastorale Passacaglia La Valse RAVEL A R S LON G A V I T A BREVIS PROGRAM NOTES "Ciaconna" (transcribed by Carlos Chavez) DIETRICH BUXTEHUDE The Ciaconna, or Chaco nne, which is identical with the Passacaglia, originated as a device in which a passage was continually repeated in a composition, usually in the same part. It should also be pointed out that the Chaco nne was used as a dance form, more particularly in the theater. The Chaconne that is performed on this occasion is a transcription for orchestra by Chavez of one originally composed for organ by Dietrich Buxtehude. The work, in E minor, is scored for two piccolos, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, three bassoons, four horns, four trumpets, three trombones, tuba, five kettledrums and strings. FELIX BOROWSKI Concerto for Trumpet in D major GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN George Philipp Telemann (1681-1767), a contemporary of Bach and Handel, was a renowned figure in the musical life of his time, in his way as famous as Handel in his, and far more widely known than Bach. -

Perspectives on Memory for Musical Timbre

Perspectives on Memory for Musical Timbre Kai Kristof Siedenburg Music Technology Area Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University Montreal, Canada March 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. c 2016 Kai Siedenburg 2016/03/29 bong bing bang bung bäng für Eliza ii Contents Abstract/Résumé .................................. vi Acknowledgments ................................. x Contribution of authors .............................. xii List of Figures ................................... xvii List of Tables .................................... xx List of Acronyms .................................. xxi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Ideas and questions ............................. 1 1.2 Methods ................................... 8 1.3 Thesis outline ................................ 9 I Background 13 2 Three conceptual distinctions for timbre 15 2.1 Introduction ................................. 15 2.2Soundeventvs.timbre........................... 16 2.3 Qualitative vs. source timbre ........................ 18 2.4 Timbre on different scales of detail .................... 19 2.5 Conclusion .................................. 21 3 A review of research on memory for timbre 23 3.1 Introduction ................................. 23 3.2 Basic concepts in memory ......................... 25 3.3 Key findings in auditory memory ..................... 28 Contents iii 3.3.1 Auditory sensory memory ..................... 29 3.3.2 Memory for noise .........................