Making Sense of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

Heer Ranjha Qissa Qawali by Zahoor Ahmad Mp3 Download

Heer ranjha qissa qawali by zahoor ahmad mp3 download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Look at most relevant Qawali heer ranjha zahoor renuzap.podarokideal.ru websites out of 15 at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Qawali heer ranjha zahoor renuzap.podarokideal.ru found at renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru and etc. Check th. Look at most relevant Heer ranjha mp3 qawali zahoor ahmad websites out of Million at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Heer ranjha mp3 qawali zahoor ahmad found at renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru and etc. Download Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad Video Video Music Download Music Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad Video, filetype:mp3 listen Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad. Download Heer Ranjha Part 1 Zahoor Ahmed Mp3, heer ranjha part 1 zahoor ahmed, malik shani, , PT30M6S, MB, ,, 2,, , , , download-heer- ranjha-partzahoor-ahmed-mp3, WOMUSIC, renuzap.podarokideal.ru Download Planet Music Heer Ranjha Full Qawwali By Zahoor Ahmad Mp3, Metrolagu Heer Ranjha. Home» Download zahoor ahmed maqbool ahmed qawwal heer ranjha part 1 play in 3GP MP4 FLV MP3 available in p, p, p, p video formats.. Heer ni ranjha jogi ho gaya - . · Qawali pharr wanjhli badal taqdeer ranjhna teri wanjhli ty lgi hoi heer ranjhna.. (punjabi spirtual ghazal by arif feroz khan) Qawali pharr wanjhli badal taqdeer ranjhna teri wanjhli ty lgi hoi heer ranjhna.. (punjabi spirtual ghazal by arif feroz khan) Heer Ranjha Full Qawwali By Zahoor Ahmad - Duration: Khurram Rasheed , views. Heer is an extremely beautiful woman, born into a wealthy family of the Sial tribe in Jhang which is now Punjab, renuzap.podarokideal.ru (whose first name is Dheedo; Ranjha is the surname, his caste is Ranjha), a Jat of the Ranjha tribe, is the youngest of four brothers and lives in the village of Takht Hazara by the river renuzap.podarokideal.ru his father's favorite son, unlike his brothers who had to toil in. -

Poem for Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan Ending in a Beginning

Poem for Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan ending in a beginning Yours is the music of quiet 4am, of solitary afternoons that seem unending. Yours the music of desire, the exhale of the Urdu word for ‘need’, like the sound of a lung first learning breath. Yours the shape of my father’s mouth turning into song. Yours the voice of sandpaper and husk, like the call for God coming out of a garbage truck throat. Yours the voice of surrender, surrender, surrender to the longing of the living, to all bottomless need to be filled, to find another, to be whole. Yours the poet’s knowledge of how to moan a word, yours the low humming of all the world’s restless stirring. Yours the yearning, the always and forever yearning, yours the trembling lips of a muted string waiting to burst into passion. Yours the hunger of a fakir who has forsaken begging to shout from the rooftops. Yours the sweet wine of grief, the unbridled intoxication which you deliver like a lover’s return. Yours the lust. Yours the notes that land like a hand tapping on the tight drumskin of my heart, then the strum of the harmonica which struggles to keep up with your voice soaring into the sky. Yours the utterance of devotion, yours the prophet’s chant, yours the treacherous winding road harmony, yours the fevered ecstasy. Yours a wild animal wail from before words, the sound of the soul freed of the ribcage, from some ancient deep forgotten history, yours every exuberant end yours every troubled beginning. -

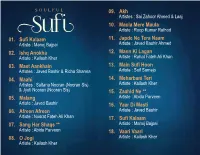

Soulful SUFI Booklet Copy

SOULFUL 09. Akh Artistes : Sai Zahoor Ahmed & Laaj 10. Maula Mere Maula Artiste : Roop Kumar Rathod 01. Sufi Kalaam 11. Japde Ne Tera Naam Artiste : Manoj Bajpai Artiste : Javed Bashir Ahmed 02. Ishq Anokha 12. Mann Ki Lagan Artiste : Kailash Kher Artiste : Rahat Fateh Ali Khan 03. Mast Aankhain 13. Main Sufi Hoon Artistes : Javed Bashir & Richa Sharma Artiste : Saif Samejo 04. Maahi 14. Meharbani Teri Artistes : Sultana Nooran (Nooran Sis) Artiste : Kailash Kher & Jyoti Nooran (Nooran Sis) 15. Zaahid Ne ** 05. Malang Artiste : Abida Parveen Artiste : Javed Bashir 16. Yaar Di Masti 06. Afreen Afreen Artiste : Javed Bashir Artiste : Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan 17. Sufi Kalaam 07. Sang Har Shaqs ** Artiste : Manoj Bajpai Artiste : Abida Parveen 18. Vaari Vaari 08. O Jogi Artiste : Kailash Kher Artiste : Kailash Kher 1 2 19. Bulleya Ki Jaana Main Kaun ** 28. Siyah Tara Artiste : Wadali Brothers Artiste : Kailash Kher 20. Bulleh Shah ** 29. Aaj Hona Deedar Mahi Da Artiste : Shafqat Amanat Ali (Medley) ** Artiste : Saleem 21. Mast Qalandar Artiste : Javed Bashir 30. Tere Ishq Nachaya ** Artiste : Wadali Brothers 22. Berukhiyan Artiste : Kailash Kher 31. Ranjha ** Artiste : Jasbir Jassi 23. Tere Ishq Nachaya ** Artiste : Hans Raj Hans 32. Turiya Turiya Artiste : Kailash Kher 24. Nadana Artiste : Javed Bashir 33. Sufi Kalaam Artiste : Manoj Bajpai 25. Dagar Panghat Ki ** Artiste : Shahid Ahmed Warsi 34. Alif Allah Chambey Di Butti Artiste : Chintoo Singh 26. Guru Ghantaal Artiste : Kailash Kher 35. Chhaap Tilak ** Artiste : Zila Khan 27. Sanu Ik Pal Artiste : Javed Bashir 36. Maula Maula - 2012 Artiste : Ustad Shujat Khan 3 4 37. Tumba- Prince Ghuman Feat. -

Coke Studio Pakistan: an Ode to Eastern Music with a Western Touch

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Coke Studio Pakistan: An Ode to Eastern Music with a Western Touch SHAHWAR KIBRIA Shahwar Kibria ([email protected]) is a research scholar at the School of Arts and Aesthetics at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Vol. 55, Issue No. 12, 21 Mar, 2020 Since it was first aired in 2008, Coke Studio Pakistan has emerged as an unprecedented musical movement in South Asia. It has revitalised traditional and Eastern classical music of South Asia by incorporating contemporary Western music instrumentation and new-age production elements. Under the religious nationalism of military dictator Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, the production and dissemination of creative arts were curtailed in Pakistan between 1977 and 1988. Incidentally, the censure against artistic and creative practice also coincided with the transnational movement of qawwali art form as prominent qawwals began carrying it outside Pakistan. American audiences were first exposed to qawwali in 1978 when Gulam Farid Sabri and Maqbool Ahmed Sabri performed at New York’s iconic Carnegie Hall. The performance was referred to as the “aural equivalent of the dancing dervishes” in the New York Times (Rockwell 1979). However, it was not until Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s performance at the popular World of Music, Arts and Dance (WOMAD) festival in 1985 in Colchester, England, following his collaboration with Peter Gabriel, that qawwali became evident in the global music cultures. Khan pioneered the fusion of Eastern vocals and Western instrumentation, and such a coming together of different musical elements was witnessed in several albums he worked for subsequently. Some of them include "Mustt Mustt" in 1990 ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 and "Night Song" in 1996 with Canadian musician Michael Brook, the music score for the film The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) and a soundtrack album for the film Dead Man Walking (1996) with Peter Gabriel, and a collaborative project with Eddie Vedder of the rock band Pearl Jam. -

Economic Impact of the Recorded Music Industry in India September 2019 Economic Impact of the Recorded Music Industry in India

Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India September 2019 Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Contents Foreword by IMI 04 Foreword by Deloitte India 05 Glossary 06 Executive summary 08 Indian recorded music industry: Size and growth 11 Indian music’s place in the world: Punching below its weight 13 An introduction to economic impact: The amplification effect 14 Indian recorded music industry: First order impact 17 “Formal” partner industries: Powered by music 18 TV broadcasting 18 FM radio 20 Live events 21 Films 22 Audio streaming OTT 24 Summary of impact at formal partner industries 25 Informal usage of music: The invisible hand 26 A peek into brass bands 27 Typical brass band structure 28 Revenue model 28 A glimpse into the lives of band members 30 Challenges faced by brass bands 31 Deep connection with music 31 Impact beyond the numbers: Counts, but cannot be counted 32 Challenges faced by the industry: Hurdles to growth 35 Way forward: Laying the foundation for growth 40 Concluding remarks: Unlocking the amplification effect of music 45 Acknowledgements 48 03 Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Foreword by IMI Foreword by Deloitte India CIRCA 2019: the story of the recorded Nusrat Fateh Ali-Khan, Noor Jehan, Abida “I know you may not At the Indian Music Convention: Dialogue Not everything that counts can be music industry would be that of David Parveen, Runa Laila, and, of course, the in August 2018, IMI had announced counted. -

Pakistaniat', a Way Forward to Also Acknowledged and Appreciated Pakistan’S Steps We Take, Are in Our Own Interest

"The UN must play that role of responsibility which is due. The Kashmir dispute is a reality and no one can deny it or remove it from the UNSC agenda" Foreign Minister of Pakistan SHAH MEHMOOD QURESHI Thewww.theasiantelegraph.net AsianSunday June 27,Telegraph 2021 | Vol: XII, Issue: 64 ABC CERTIFIED /asian_telegraph /asian_telegraph w us /theasiantelegraph /asian_telegraph w us /theasiantelegraph /company/theasiantelegraph /theasiantelegraph /company/theasiantelegraph ollo .theasiantelegraph.net /asian_teleg/asian_telegraphraph /company/theasiantelegraph F Price Rs 8| Pages 4 w us /theasiantelegraph .theasiantelegraph.net ollo F w us /theasiantelegraph /company/theasiantelegraph .theasiantelegraph.net /company/theasiantelegraph ollo F .theasiantelegraph.net 'Noollo room' to keep Pakistan accords foremost F .theasiantelegraph.net Pakistan on grey list: priority to combatting FM Qureshi drug abuse, President President Calls For Joint Efforts To Check Cross Some Powers Desire To Keep The Sword Of Fatf Hanging Over Pakistan Border Drug Trade ISLAMABAD ISLAMABAD Every year the International Drug Day is Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi on Saturday celebrated on 26 June as a reminder to all, said there was "no room" to keep Pakistan on the including the world leaders, international Financial Action Task Force's (FATF) grey list and community, global alliances and associations of wondered if the body is a technical or a political forum. our shared responsibility to fight the menace of The foreign minister's statement came a day after the illicit trading and trafficking in drugs through joint watchdog retained Pakistan on its grey list despite the collaborative efforts. On this day, we reaffirm our country meeting 26 out of 27 conditions. Pakistan resolve to curb and eliminate trade in narcotics was also given a new six-point action plan, keeping and banned substances posing serious danger to Islamabad exposed to global pressure tactics. -

The Use of Performance As a Tool for Communicating Islamic Ideas and Teachings

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE USE OF PERFORMANCE AS A TOOL FOR COMMUNICATING ISLAMIC IDEAS AND TEACHINGS By RAHEES KASAR A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion Department of Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham July 2015 i University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. GLOSSARY Allah Arabic word for God Da’wah To call, to invite Islah Revival Balag Proclamation Dawat Islami A da’wah group, invitation to Islam Tablighi Jamaat Da’wah Group, Society for spreading faith Hikaya Tale or narrative Tamtheel Pretention Khayaal Imagination Ta’ziyah Shia passion plays Fiqh Islamic law Aqeedah Creed Sunnah Prophet Tradition Ummah Muslim Community ii ABSTRACT The emergence and growth of performance for the purpose of communicating Islamic ideas and teachings is a topic that has gained popularity with no real academic research, which is vital as it is utilised as a tool for da’wah, propagation and communication. -

VOL 16 NO 2Electrnic

anif’s QUALITY SINCE 1973 31A Central Avenue - Mayfar- 011 839 2064 Shop No. 3 Falcon Street Ext 1- Lenasia 011 852 1746 Volume 16 Number 2 1727 Lenasia 1820 011854-4543 011854-7886 2 SAFAR 1434/2012 GUARD YOUR IMAAN! Avoid the office parties! Avoid mass Truly, what's your agenda? Just need celebrations and avoid public places as far as a break, a bit of loosening up, letting your possible! If you have to socialise keep hair down? Pray there's no lasting damage! company with good people who respect their Pray its not your time! Islamic values. Malakul Mauwt. In an instant you No excuses please. As muslims you shed your imaan, and in that instant there he should know what you have to do and what stands before you! not to do at this time. Festive Season is usually welcomed with the aplomb of some religious This is the season of alcohol, drugs, occasion. and promiscuity! Is this for us? Not safe anywhere and not safe the company of Religious? Perhaps in the Shaytaani dubious fence-sitters. context. Lock your doors and keep the kids where you can see them. (The doors of No time for 'talk'...let's 'walk' together NAFS!) upon Siratul Mustaqeem! There are anti-Allah forces rampant, Here, insha Allah is good company. visible and also invisible, waiting to do a quick La tah'zan Innallaha ma'anaa! al-Quran 'smash and grab' on your imaan and your (Don't despair, Allah is with US!) soul. Are you available for this? Are you May Allah save us and our secretly hoping something like this could or community! May Allah preserve Islam and would happen? There are those who nakedly the ummah of His Beloved Muhammad r ! court it, others who secretly desire it, and some (Alhamdulillah) who detest it. -

General Awareness Questions 3Rd March Shift 3 Q1

GENERAL AWARENESS QUESTIONS 3RD MARCH SHIFT 3 Q1. Name the Indian elected to the International Narcotics Board by the UN Economic and Social Council on 23 April 2014 and re-elected by the Council for a 5-year term (2020-2025) on 7th May 2019. 1. Sudhir Rajkumar 2. Jagjit Pavadia 3. Syed Akbaruddin 4. Yasmin Ali Haque Q2. Hiuen Tsang, hailed as the prince of pilgrims, visited Indian during the reign of king_____. 1. Ashoka 2. Vishnugupta 3. Harsha 4. Samudragupta Q3. As of January 2020, which of the following countries had not independently launched a human into space? 1. USA 2. Russia 3. India 4. China Q4. The city of ______ is located at the mouth of the Yangtze river. 1. Guangzhou 2. Beijing 3. Shanghai 4. Lhasa Q5. Who among the following publishes the Economic Survey of India? 1. Ministry of Finance 2. Indian Statstical Institute 3. Institute of Finance 4. National Development Council Q6. As of December 2019, _____ was the largest crude oil supplier to India. 1. Iran 2. United Arab Emirates 3. Iraq 4. Saudi Arabia Q7. 'Kiribath' is a rice dish from ______. 1. Bhutan 2. Nepal 3. Sri Lanka 4. Myanmar Q8. Who among the following was a famous 'Qawwali' singer? 1. Bade Ghulam Ali Khan 2. Begum Akhtar 3. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan 4. Nazia Hassan Q9. The birth anniversary of _____ is celeberated as 'International Nurses day' every year. 1. Clara Barton 2. Florence Nightingale 3. Mother Teresa 4. Alice Walker Q10. In ______ economies, all productive resources are owned and controlled by the governemnt. -

Downloaded Pakistani Song of the Year of Its Release

ROCKISTAN HISTORY OF THE MOST TURBULENT MUSIC GENRE IN PAKISTAN ROCKISTAN HISTORY OF THE MOST TURBULENT MUSIC GENRE IN PAKISTAN TAYYAB KHALIL COVER DESIGNED BY ANUM AMEER Copyright © 2021 by Tayyab Khalil All rights reserved This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review ISBN: 978-969-23555-0-6 (Hard cover) ISBN: 978-969-23555-1-3 (E-book) Daastan Publications Floor # 1, Workspace 2, Office # 3, National Incubation Center, Islamabad Phone: +92-3219525753 Email: [email protected] www.daastan.com CONTENTS Preface 8 1. Only a Music Concert 11 2. A Game of Chance 20 3. Emergence of the Vital Empire 29 4. An Unholy Alliance 74 5. The Double-edged Sword 115 6. Underground Reverberations 169 7. Unveiling the Partition 236 8. Rock Renaissance 257 9. The Unconventional Path 315 10. Political Upheaval 344 11. Dimes, Crimes and Hard Times 368 12. Tragedy to Triumph 433 Acknowledgements 459 8 PREFACE The road travelled by Pakistani rock musicians is beset with challenges such as staunch criticism, struggling to have a socially acceptable image, having the door slammed in the face by record label owners and lowball offers by concert organizers. Not only are their careers mentally grueling and physically demanding but they also have an added risk of high investment and low returns. The rock genre has struggled to achieve its righteous place in the country whereas folk, qawalli, pop, bhangra and Bollywood music experienced skyrocketing popularity. -

Songs from the Other Side: Listening to Pakistani Voices in India

SONGS FROM THE OTHER SIDE: LISTENING TO PAKISTANI VOICES IN INDIA John Shields Caldwell A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music (Musicology). Chapel Hill 2021 Approved by: Michael Figueroa Jayson Beaster-Jones David Garcia Mark Katz Pavitra Sundar © 2021 John Shields Caldwell ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT John Shields Caldwell: Songs from the Other Side: Listening to Pakistani Voices in India (Under the direction of Michael Figueroa) In this dissertation I investigate how Indian listeners have listened to Pakistani songs and singing voices in the period between the 1970s and the present. Since Indian film music dominates the South Asian cultural landscape, I argue that the movement of Pakistani songs into India is both a form of resistance and a mode of cultural diplomacy. Although the two nations share a common history and an official language, cultural flows between India and Pakistan have been impeded by decades of political enmity and restrictions on trade and travel, such that Pakistani music has generally not been able to find a foothold in the Indian songscape. I chart the few historical moments of exception when Pakistani songs and voices have found particular vectors of transmission by which they have reached Indian listeners. These moments include: the vinyl invasion of the 1970s, when the Indian market for recorded ghazal was dominated by Pakistani artists; two separate periods in the 1980s and 2000s when Pakistani female and male vocalists respectively sang playback in Indian films; the first decade of the new millennium when international Sufi music festivals brought Pakistani singers to India; and the 2010s, when Pakistani artists participated extensively in television music competition shows.