Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVT-PUNJAB Waitinglist Nphs.Pdf

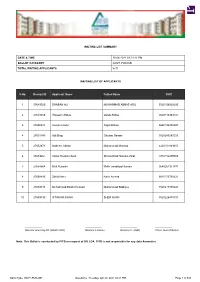

WAITING LIST SUMMARY DATE & TIME 20-04-2021 02:21:11 PM BALLOT CATEGORY GOVT-PUNJAB TOTAL WAITING APPLICANTS 8711 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 1 27649520 SHABAN ALI MUHAMMAD ABBAS ADIL 3520106922295 2 27649658 Waseem Abbas Qalab Abbas 3520113383737 3 27650644 Usman Hiader Sajid Abbasi 3650156358657 4 27651140 Adil Baig Ghulam Sarwar 3520240247205 5 27652673 Nadeem Akhtar Muhammad Mumtaz 4220101849351 6 27653461 Imtiaz Hussain Zaidi Shasmshad Hussain Zaidi 3110116479593 7 27654564 Bilal Hussain Malik tasadduq Hussain 3640261377911 8 27658485 Zahid Nazir Nazir Ahmed 3540173750321 9 27659188 Muhammad Bashir Hussain Muhammad Siddique 3520219305241 10 27659190 IFTIKHAR KHAN SHER KHAN 3520226475101 ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- Director Housing-XII (LDAC NPA) Director Finance Director IT (I&O) Chief Town Planner Note: This Ballot is conducted by PITB on request of DG LDA. PITB is not responsible for any data Anomalies. Ballot Type: GOVT-PUNJAB Date&time : Tuesday, Apr 20, 2021 02:21 PM Page 1 of 545 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 11 27659898 Maqbool Ahmad Muhammad Anar Khan 3440105267405 12 27660478 Imran Yasin Muhammad Yasin 3540219620181 13 27661528 MIAN AZIZ UR REHMAN MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520225181377 14 27664375 HINA SHAHZAD MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD ARIF 3520240001944 15 27664446 SAIRA JABEEN RAZA ALI 3110205697908 16 27664597 Maded Ali Muhammad Boota 3530223352053 17 27664664 Muhammad Imran MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520223937489 -

Judicial Officers Interested for 1 Kanal Plots-Jalozai

JUDICIAL OFFICERS INTERESTED FOR 1 KANAL PLOTS‐JALOZAI S.No Emp_name Designation Working District 1 Mr. Anwar Ali District & Sessions Judge, Peshawar 2 Mr. Sharif Ahmad Member Inspection Team, Peshawar High Court, Peshawar 3 Mr. Ishtiaq Ahmad Administrative Judge, Accountability Courts, Peshawar 4 Syed Kamal Hussain Shah Judge, Anti‐Corruption (Central), Peshawar 5 Mr. Khawaja Wajih‐ud‐Din OSD, Peshawar High Court, Peshawar 6 Mr. Fazal Subhan Judge, Anti‐Terrorism Court, Abbottabad 7 Mr. Shahid Khan Administrative Judge, ATC Courts, Malakand Division, Dir Lower (Timergara) 8 Dr. Khurshid Iqbal Director General, KP Judicial Academy, Peshawar 9 Mr. Muhammad Younas Khan Judge, Anti‐Terrorism Court, Mardan 10 Mrs. Farah Jamshed Judge on Special Task, Peshawar 11 Mr. Inamullah Khan District & Sessions Judge, D.I.Khan 12 Mr. Muhammad Younis Judge on Special Task, Peshawar 13 Mr. Muhammad Adil Khan District & Sessions Judge, Swabi 14 Mr. Muhammad Hamid Mughal Member, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Service Tribunal, Peshawar 15 Mr. Shafiq Ahmad Tanoli OSD, Peshawar High Court, Peshawar 16 Mr. Babar Ali Khan Judge, Anti‐Terrorism Court, Bannu 17 Mr. Abdul Ghafoor Qureshi Judge, Special Ehtesab Court, Peshawar 18 Mr. Muhammad Tariq Chairman, Drug Court, Peshawar 19 Mr. Muhammad Asif Khan District & Sessions Judge, Hangu 20 Mr. Muhammad Iqbal Khan Judge on Special Task, Peshawar 21 Mr. Nasrullah Khan Gandapur District & Sessions Judge, Karak 22 Mr. Ikhtiar Khan District & Sessions Judge, Buner Relieved to join his new assingment as Judge, 23 Mr. Naveed Ahmad Khan Accountability Court‐IV, Peshawar 24 Mr. Ahmad Sultan Tareen District & Sessions Judge, Kohat 25 Mr. Gohar Rehman District & Sessions Judge, Dir Lower (Timergara) Additional Member Inspection Team, Secretariat for 26 Mr. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

Schedule for Written Test for the Posts of Lecturers in Various Disciplines

SCHEDULE FOR WRITTEN TEST FOR THE POSTS OF LECTURERS IN VARIOUS DISCIPLINES Please be informed that written test for the posts of Lecturers in the following departments / disciplines shall be conducted by the University of Sargodha as per schedule mentioned below: Post Applied for: Date & Time Venue 16.09.2018 Department of Business LECTURER IN LAW (Sunday) Administration, (MAIN CAMPUS) University of Sargodha, 09:30 am Sargodha. Roll # Name & Father’s Name 1. Mr. Ahmed Waqas S/o Abdul Sattar 2. Ms. Mahwish Mubeen D/o Mumtaz Khan 3. Malik Sakhi Sultan Awan S/o Malik Abdul Qayum Awan 4. Ms. Sadia Perveen D/o Manzoor Hussain 5. Mr. Hassan Nawaz Maken S/o Muhammad Nawaz Maken 6. Mr. Dilshad Ahmed S/o Abdul Razzaq 7. Mr. Muhammad Kamal Shah S/o Mufariq Shah 8. Mr. Imtiaz Ali S/o Sahib Dino Soomro 9. Mr. Shakeel Ahmad S/o Qazi Rafiq Ahmad 10. Ms. Hina Sahar D/o Muhammad Ashraf 11. Ms. Tahira Yasmeen D/o Sheikh Nazar Hussain 12. Mr. Muhammad Kamran Akbar S/o Mureed Hashim Khan 13. Mr. M. Ahsan Iqbal Hashmi S/o Makhdoom Iqbal Hussain Hashmi 14. Mr. Muhammad Faiq Butt S/o Nazzam Din Butt 15. Mr. Muhammad Saleem S/o Ghulam Yasin 16. Ms. Saira Afzal D/o Muhammad Afzal 17. Ms. Rubia Riaz D/o Riaz Ahmad 18. Mr. Muhammad Sarfraz S/o Ijaz Ahmed 19. Mr. Muhammad Ali Khan S/o Farzand Ali Khan 20. Mr. Safdar Hayat S/o Muhammad Hayat 21. Ms. Mehwish Waqas Rana D/o Muhammad Waqas 22. -

War in Pakistan: the Effects of the Pakistani-American War on Terror in Pakistan

WAR IN PAKISTAN: THE EFFECTS OF THE PAKISTANI-AMERICAN WAR ON TERROR IN PAKISTAN by AKHTAR QURESHI A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Political Science in the College of Science and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2011 Thesis Chair: Dr. Houman Sadri ABSTRACT This research paper investigates the current turmoil in Pakistan and how much of it has been caused by the joint American-Pakistani War on Terror. The United States’ portion of the War on Terror is in Afghanistan against the Al-Qaeda and Taliban forces that began after the September 11th attacks in 2001, as well as in Pakistan with unmanned drone attacks. Pakistan’s portion of this war includes the support to the U.S. in Afghanistan and military campaigns within it’s own borders against Taliban forces. Taliban forces have fought back against Pakistan with terrorist attacks and bombings that continue to ravage the nation. There have been a number of consequences from this war upon Pakistani society, one of particular importance to the U.S. is the increased anti-American sentiment. The war has also resulted in weak and widely unpopular leaders. The final major consequence this study examines is the increased conflict amongst the many ethnicities within Pakistan. The consequences of this war have had an effect on local, regional, American, and international politics. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I express sincere thanks and gratitude to my committee members, who have been gracious enough to enable this project with their guidance, wisdom, and experience. -

Imsk Week for Everyone in the Business of Ivlusic 13 MOVEMBER 1993 £2.8

imsk week For Everyone in the Business of IVlusic 13 MOVEMBER 1993 £2.8 BPI: pil himnow The music industry has roundly con- Keely Gilbert, of Chris Rea's man- Highdemned Court the judge warning last metedweek to eut alleged by a wasagement able toReal order Life, video says bootlegs the company of Rea's bootleggerCharlesworth, Stephen previously Charlesworth. of Clwyd- threeconcerts months by phone. to arrive "They and took were about rub- guilty in the High Court of breaching judgebish," isn'tshe muchadds. of "A a punishment."warning from a latingan injunction leaflets stopping advertising him from circu-video APUThe on case Designatec's arose from premises a raid inby May, the That,bootlegs Chris of Rea,top artistsand Peter such Gabriel. as Take CharlesworthMr Justice to payFerris the costs ordered of the behalfBPI, which of sixhad memberbrought thecompanies. case on Charlesworth was also wamed that and July 26 the BPI wouid have ceedingsSubsequently for conte. tl : BPI bi CourtStephen last Charlesworth week after heing leaves found the inHigh And warning to pii pirated acts unauthorised Take That_ he videoshad offered and contempt of an injunction restraining "It's laughable," says lan Grant, mai tapesCharlesworth for sale in July. appeared in the High advertisinghim from circulating pirate audio leaflets and hootleg iEVERLEY plainedager of inBig the Country, past of leafletswho has offerin con Court ins Septemberadjourned' for " but s1 the proceed-' until video cassettes. Charlesworth, of video bootlegs of the band. This maki photographerClwyd, -

M.A Urdu and Iqbaliat

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Notification No. 37/CS M.A. Urdu and Iqbaliat (Composite) Supplementary Examination, 2019 It is hereby notified that the result of the following External/Private candidates of the Master of Arts Composite Supplementary Examination, 2019 held in Feb, 2021 in the subject of Urdu and Iqbaliat has been declared as under: Maximum Marks in this Examination : 1100 Minimum Pass Marks : 40 % This notification is issued as a notice only. Errors and omissions excepted. An entry appearing in it does not in itself confer any right or privilege independently to the grant of a proper Certificate/Degree which will be issued under the Regulations in due Course. -4E -1E Appeared: 3515 Passed: 1411 Pass Percentage: 40.14 % Roll# Regd. No Name and Father's Name Result Marks Div Papers to reappear and chance II IV V VII XI 16251 07-WR-441 GHZAL SAIIF Fail SAIF-U-LLAH R/A till A-22 III V VII 16252 09-IB.b-3182 Mudssarah Kousar Fail Muhammad Aslam R/A till S-22 II IV V VI VII 16253 2012-WR-293 Sonia Hamid Fail Abdul Hamid R/A till S-22 III V VI VII VIII IX 16254 2013-IWS-46 Ifra Shafqat Fail Shafqat Nawaz R/A till S-22 III VI VII VIII IX 16255 2012-IWS-238 Fahmeeda Tariq Fail Tariq Mahmood R/A till S-22 II VII VIII IX XII XIII 16256 2019-IUP(M-II)- Rehana Kouser Fail 00079 Dilber Ali R/A till S-22 IV V VI VII IX 16257 2012-WR-115 Faiza Masood Fail Masood Habib Adil R/A till S-22 III IV V VI VII 16258 02-WR-362 Nayyer Sultana Fail Rahmat Ali R/A till S-22 III IV VI VII VIII IX 16259 2015-WR-151 Rafia Parveen Fail Noor Muhammad -

Disco Top 15 Histories

10. Billboard’s Disco Top 15, Oct 1974- Jul 1981 Recording, Act, Chart Debut Date Disco Top 15 Chart History Peak R&B, Pop Action Satisfaction, Melody Stewart, 11/15/80 14-14-9-9-9-9-10-10 x, x African Symphony, Van McCoy, 12/14/74 15-15-12-13-14 x, x After Dark, Pattie Brooks, 4/29/78 15-6-4-2-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-3-3-5-5-5-10-13 x, x Ai No Corrida, Quincy Jones, 3/14/81 15-9-8-7-7-7-5-3-3-3-3-8-10 10,28 Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us, McFadden & Whitehead, 5/5/79 14-12-11-10-10-10-10 1,13 Ain’t That Enough For You, JDavisMonsterOrch, 9/2/78 13-11-7-5-4-4-7-9-13 x,89 All American Girls, Sister Sledge, 2/21/81 14-9-8-6-6-10-11 3,79 All Night Thing, Invisible Man’s Band, 3/1/80 15-14-13-12-10-10 9,45 Always There, Side Effect, 6/10/76 15-14-12-13 56,x And The Beat Goes On, Whispers, 1/12/80 13-2-2-2-1-1-2-3-3-4-11-15 1,19 And You Call That Love, Vernon Burch, 2/22/75 15-14-13-13-12-8-7-9-12 x,x Another One Bites The Dust, Queen, 8/16/80 6-6-3-3-2-2-2-3-7-12 2,1 Another Star, Stevie Wonder, 10/23/76 13-13-12-6-5-3-2-3-3-3-5-8 18,32 Are You Ready For This, The Brothers, 4/26/75 15-14-13-15 x,x Ask Me, Ecstasy,Passion,Pain, 10/26/74 2-4-2-6-9-8-9-7-9-13post peak 19,52 At Midnight, T-Connection, 1/6/79 10-8-7-3-3-8-6-8-14 32,56 Baby Face, Wing & A Prayer, 11/6/75 13-5-2-2-1-3-2-4-6-9-14 32,14 Back Together Again, R Flack & D Hathaway, 4/12/80 15-11-9-6-6-6-7-8-15 18,56 Bad Girls, Donna Summer, 5/5/79 2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-10-13 1,1 Bad Luck, H Melvin, 2/15/75 12-4-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-4-5-5-7-10-15 4,15 Bang A Gong, Witch Queen, 3/10/79 12-11-9-8-15 -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

Heer Ranjha Qissa Qawali by Zahoor Ahmad Mp3 Download

Heer ranjha qissa qawali by zahoor ahmad mp3 download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Look at most relevant Qawali heer ranjha zahoor renuzap.podarokideal.ru websites out of 15 at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Qawali heer ranjha zahoor renuzap.podarokideal.ru found at renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru and etc. Check th. Look at most relevant Heer ranjha mp3 qawali zahoor ahmad websites out of Million at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Heer ranjha mp3 qawali zahoor ahmad found at renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru and etc. Download Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad Video Video Music Download Music Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad Video, filetype:mp3 listen Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad. Download Heer Ranjha Part 1 Zahoor Ahmed Mp3, heer ranjha part 1 zahoor ahmed, malik shani, , PT30M6S, MB, ,, 2,, , , , download-heer- ranjha-partzahoor-ahmed-mp3, WOMUSIC, renuzap.podarokideal.ru Download Planet Music Heer Ranjha Full Qawwali By Zahoor Ahmad Mp3, Metrolagu Heer Ranjha. Home» Download zahoor ahmed maqbool ahmed qawwal heer ranjha part 1 play in 3GP MP4 FLV MP3 available in p, p, p, p video formats.. Heer ni ranjha jogi ho gaya - . · Qawali pharr wanjhli badal taqdeer ranjhna teri wanjhli ty lgi hoi heer ranjhna.. (punjabi spirtual ghazal by arif feroz khan) Qawali pharr wanjhli badal taqdeer ranjhna teri wanjhli ty lgi hoi heer ranjhna.. (punjabi spirtual ghazal by arif feroz khan) Heer Ranjha Full Qawwali By Zahoor Ahmad - Duration: Khurram Rasheed , views. Heer is an extremely beautiful woman, born into a wealthy family of the Sial tribe in Jhang which is now Punjab, renuzap.podarokideal.ru (whose first name is Dheedo; Ranjha is the surname, his caste is Ranjha), a Jat of the Ranjha tribe, is the youngest of four brothers and lives in the village of Takht Hazara by the river renuzap.podarokideal.ru his father's favorite son, unlike his brothers who had to toil in. -

KLF-10 Programme 2019

Friday, 1 March 2019 Inauguration of the 10th Karachi Literature Festival Main Garden, Beach Luxury Hotel, Karachi 5.00 p.m. Arrival of Guests 5.30 p.m. Welcome Speeches by Festival Organizers 5.45 p.m. Speech by the Chief Guest: Honourable Governor Sindh, Imran Ismail Speeches by: Mark Rakestraw, Deputy Head of Mission, BDHC, Didier Talpain, Consul General of France, Enrico Alfonso Ricciardi, Deputy Head of Mission, Italian Consulate 6.00 p.m. Karachi Literature Festival-Infaq Foundation Best Urdu Literature Prize 6.05 p.m. Keynote Speeches by Zehra Nigah and Muneeza Shamsie 6.45 p.m. KLF Recollection Documentary 7.00 p.m. Aao Humwatno Raqs Karo: Performance by Sheema Kermani 7.45–8.45 p.m. Panel Discussions 9.00–9.30 p.m. Safr-e-Pakistan: Pakistan’s Travelogue in String Puppets by ThespianzTheatre MC: Ms Sidra Iqbal 7.45 p.m. – 8.45 p.m. Pakistani Cinema: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Yasir Hussain, Munawar Saeed, Nabeel Qureshi, Asif Raza Main Garden Mir, Fizza Ali Meerza, and Satish Anand Moderator: Ahmed Shah Documentary: Qalandar Code: Rise of the Divine Jasmine Feminine Atiya Khan, David C. Heath, and Syed Mehdi Raza Shah Subzwari Moderator: Arieb Azhar Aquarius Voices from Far and Near: Poetry in English Adrian Husain, Arfa Ezazi, Farida Faizullah, Room 007 Ilona Yusuf, Jaffar Khan, Moeen Faruqi, and Shireen Haroun Moderator: Salman Tarik Kureshi Book Discussion: The Begum: A Portrait of Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan by Deepa Agarwal and Tahmina Aziz Princess Akbar Liaquat Ali Khan and Javed Aly Khan Moderator: Muneeza Shamsie Saturday, 2 March 2019 Hall Sponsor Main Garden Jasmine Aquarius Room 007 Princess 11 a.m. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad.